The Lover by Silvia Moreno-Garcia Summary, Characters and Themes

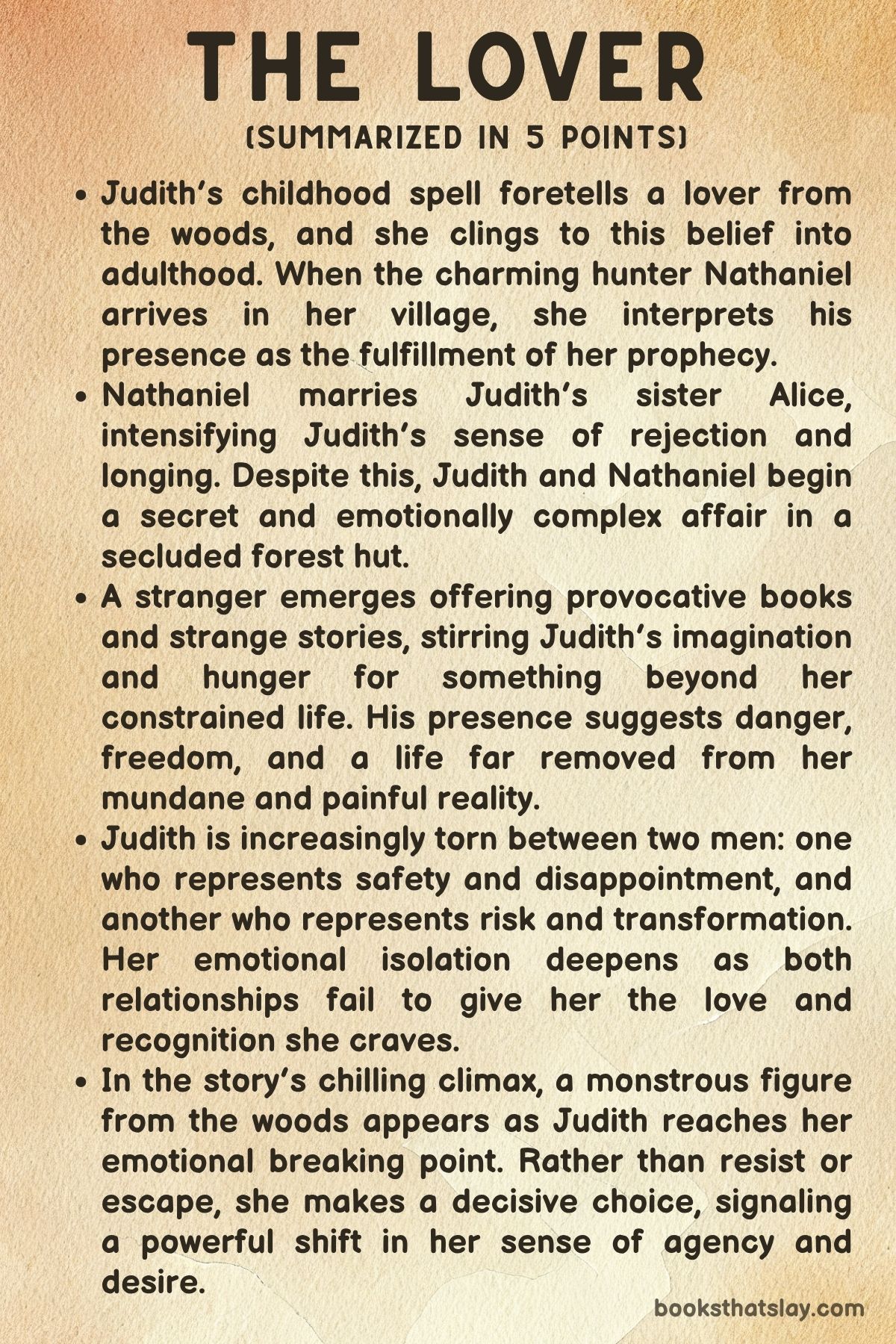

The Lover by Silvia Moreno-Garcia is a darkly romantic and eerie short story that blends emotional tension with supernatural mystery. Set in a desolate winter landscape, the tale follows Judith, a young woman grappling with feelings of invisibility, longing, and powerlessness.

Caught between her beautiful sister’s domestic bliss and her own unfulfilled desires, Judith finds herself drawn to two men: one familiar and false, the other wild and unknowable. As Judith navigates betrayal, eroticism, and a growing inner unrest, she begins to see that true liberation may lie beyond the boundaries of social expectation—and even humanity.

Through a chilling atmosphere and subtle mythic overtones, The Lover offers a psychological portrait of desire and transformation.

Summary

Judith lives in a small rural village where the cold seems eternal and isolation is an everyday companion. She performs household chores in the guesthouse owned by her elegant and adored sister, Alice.

Though Alice is admired by many, Judith is often overlooked. As a young girl, she once performed a love spell, a bit of innocent magic that foretold her future lover would come from the forest.

This prophecy lingers in her mind like a fragile hope. When a charming hunter named Nathaniel arrives during a bitter winter, Judith sees in him the fulfillment of that old spell.

He is everything the village admires—handsome, skilled, and self-assured. Judith falls for him quickly, only to be devastated when he chooses Alice instead.

Their marriage casts Judith deeper into emotional obscurity, but her yearning for Nathaniel remains. Eventually, that desire is answered, though not in a way she might have hoped.

Nathaniel initiates a secret affair with Judith, stealing away to the forest hut under the pretense of hunting trips. Their relationship is fraught with longing, guilt, and imbalance.

Nathaniel gives Judith moments of passion but never the legitimacy or affection she truly seeks. Amid this emotional turmoil, a stranger appears at the village market.

He is unkempt, odd, and strangely charismatic. He trades in oddities and stories, and gives Judith a smutty book in exchange for a kiss.

Their interactions are unpredictable and charged with a strange energy. The stranger speaks of monsters and transformations, especially of men who change into wolves.

Whether metaphor or confession, these tales stir something dangerous and compelling within Judith. The line between myth and truth begins to blur.

As winter deepens, wolves are heard howling near the village. Nathaniel, ever the outdoorsman, promises Judith he will catch one for her—a gesture meant to thrill her but one that only highlights his performative masculinity.

The stranger, by contrast, never pretends to be anything but what he is—half-riddle, half-wildness. He returns intermittently, growing more intimate and intrusive in Judith’s life, hinting at knowledge of her secrets and feelings.

He gives her a red ribbon, a token loaded with fairy tale associations—blood, seduction, fate. Alice eventually reveals her pregnancy, further pushing Judith into emotional exile.

Judith recognizes that Nathaniel never intended to leave Alice and that his promises were empty. The intimacy they shared fades into hollowness.

Even their last tryst in the forest hut feels mechanical, drained of meaning. As Nathaniel sleeps beside her that night, Judith senses something else approaching.

A wolf—enormous, silent, otherworldly—appears at the door. Rather than panic or wake Nathaniel, Judith opens the door.

In that act, she makes her choice. Whether the beast is the stranger in transformed shape or merely a symbol of Judith’s repressed desires and rage, it is clear that she welcomes him not with fear but with intention.

She offers him warmth, company, and her bed. In the final moments, Judith transforms—not physically, but emotionally and spiritually.

She no longer clings to dreams of rescue or romantic validation. She accepts the wildness, the unknowable, the dangerous.

The story ends with her embracing the presence that represents freedom from the confines of longing and subjugation. What begins as a tale of heartbreak becomes a quiet, eerie assertion of agency.

Characters

Judith

Judith is the protagonist and emotional axis of the story. She is a young woman defined by longing, disillusionment, and a hunger for something beyond her stifling existence.

From the outset, she is positioned as the overlooked sibling—plain, poor, and burdened with household labor. This stands in stark contrast to her elegant sister Alice.

Her internal world is rich with fantasy, a fact made evident by her participation in divination rituals. She romanticizes Nathaniel as the answer to a prophecy.

Judith’s yearning is not just for love, but for transcendence—a break from routine, invisibility, and domestic servitude. As she engages in a clandestine affair with Nathaniel, her passions burn intensely.

But these passions are laced with guilt, self-loathing, and a sense of emotional erosion. Her relationship with Nathaniel becomes a toxic cycle of hope and rejection.

Over time, her internal void deepens. The appearance of the mysterious stranger introduces her to a different kind of desire—dangerous, liberating, and animalistic.

Ultimately, Judith’s decision to let the beast into her home signifies a transformation. She embraces the untamed, the monstrous, as a form of self-determination.

Her arc moves from suppressed womanhood to a dark, ambiguous empowerment. In the end, the boundaries between victimhood and agency blur.

Nathaniel

Nathaniel embodies seductive masculinity and conventional charm. But beneath his rugged exterior lies a cowardly and self-serving man.

Initially perceived by Judith as the answer to her romantic destiny, he quickly becomes a symbol of betrayal and unattainable desire. He marries Alice, despite Judith’s belief in a mystical connection between them.

This sets up a triangle of suppressed rage, jealousy, and erotic tension. Nathaniel’s interactions with Judith are rooted in physical desire and emotional exploitation.

He uses her as a mistress while maintaining the social prestige of his marriage. He makes vague promises of escape and affection but retreats into the safety of his respectable life.

Nathaniel’s failure is not only in fidelity but in authenticity. He lacks the courage to truly love Judith or to confront the moral implications of his actions.

When he becomes passive in the story’s final act—sleeping in Judith’s bed while the monstrous wolf looms—it marks his symbolic irrelevance. His masculine dominance is undermined by his inertia.

Judith’s rejection of him in favor of the beast underscores his ineffectuality. He is no hero, just a shadow of one.

His presence in the narrative serves as a cautionary figure. He shows how societal norms can mask weakness and selfishness.

The Stranger / The Beast

The stranger, who may be a cursed man or a werewolf, represents the story’s gothic and mythic undertones. His character is fluid, mysterious, and primal.

He is in direct contrast to Nathaniel’s structured and civilized veneer. He enters Judith’s life not with courtship, but with provocation.

He offers her bawdy books in exchange for a kiss. He spins tales of monsters and tests the limits of her desire.

He is not merely a tempter; he is an invitation to wildness and otherness. He represents the urge to embrace what is forbidden or feared.

His transformation into a wolf is both literal and symbolic. It stands for suppressed instincts, feminine rage, and sexual autonomy.

Unlike Nathaniel, the stranger doesn’t promise love or stability. Instead, he offers danger, transgression, and the thrill of surrender.

Judith’s fascination with him grows as her disenchantment with Nathaniel deepens. By the story’s end, the beast has become her true lover.

Perhaps he is even a projection of her own repressed self. His character destabilizes the binary of man and monster, seducer and liberator.

In choosing him, Judith chooses to live within that liminal space herself. He invites the reader to question whether her choice is madness or liberation.

Alice

Alice plays a critical symbolic role as the embodiment of conventional femininity and societal acceptance. She is beautiful, poised, and effortlessly draws affection.

She marries Nathaniel, attracting him away from Judith. Through Judith’s eyes, Alice becomes a figure of resentment.

She represents everything Judith is not. Her power is quiet but absolute, grounded in her ability to conform to social expectations.

Alice is not portrayed as malicious or intentionally cruel. Rather, she is indifferent to Judith’s anguish.

Her pregnancy toward the end of the story signals fertility and domestic completion. It reinforces patriarchal norms and further isolates Judith.

Alice’s role is not to antagonize directly. Instead, she reflects the kind of life Judith is both denied and, ultimately, rejects.

She is the mirror image of Judith’s failed aspirations. Her passive dominance sharpens the protagonist’s sense of displacement.

Themes

Obsession and Unfulfilled Desire

The theme of obsession runs throughout Judith’s journey. It defines her inner life and shapes her actions with escalating intensity.

Judith’s longing begins as a young girl, prompted by a divination ritual that plants the seed of fantasy and anticipation in her mind. She waits for a lover from the forest, and when Nathaniel arrives, she believes fate has answered.

Her fixation on him is less about who he actually is and more about what he symbolizes: escape, validation, and transformation from a mundane, servile life into one of passion and meaning. Nathaniel becomes the embodiment of her deepest needs.

Even when he chooses Alice over her, Judith cannot let go. The fact that she continues to pursue him after his betrayal underscores how obsession overrides logic, dignity, and morality.

The clandestine affair is marked not by fulfillment, but by a deepening sense of emptiness and guilt. Judith’s desire becomes self-consuming.

She is no longer a participant in a mutual romance but a prisoner of her own yearning. Her craving for Nathaniel persists even as he fails her repeatedly.

He uses her in ways that reflect his own weaknesses rather than any true emotional reciprocity. This obsessive longing is counterposed by the stranger who appears without obligation or explanation, and who never hides his monstrous nature.

When Judith finally chooses the beast, it is not simply an act of liberation but a recognition that what she has desired all along was not a man, but a force strong enough to match her own intensity. Her obsession burns away into transformation, but only after consuming nearly everything else inside her.

Female Agency and Power

Judith’s arc in The Lover is fundamentally one of reclaimed agency. Her path is circuitous and steeped in pain.

From the outset, Judith is cast in the role of the lesser sister, relegated to cleaning, cooking, and obeying while Alice enjoys status, beauty, and attention. Judith’s world is one of limitation and quiet humiliation.

Her voice is muffled within domestic and societal expectations. Her spell to summon a lover might seem like a childish game, but it is also an early attempt to exert control over her future.

That the predicted man arrives and then promptly marries her sister only serves to reinforce her lack of power. Yet even in her limited position, Judith refuses to accept passive despair.

She makes the decision to begin an affair, knowing full well the consequences. Her complicity is not weakness—it is a means of carving out some semblance of choice, even if the terms are unfair.

When the stranger introduces tales of transformation and monstrous freedom, Judith is intrigued. He does not offer security or even kindness, but he speaks of power and change, things she has never had access to.

Books become another source of autonomy, igniting ideas and possibilities outside the rigid moral framework that has defined her life. In the final act, when the wolf appears and Judith chooses to open the door, she does so not out of surrender but from a place of decision.

The gesture is radical not because it defies Nathaniel, but because it affirms Judith’s own values. She is willing to embrace something wild and unknown rather than continue in passive, powerless longing.

It is a reclaiming of selfhood through a deliberate break from human constraints.

Betrayal and Emotional Exploitation

The emotional terrain of The Lover is carved by betrayal—both personal and systemic. It is this betrayal that strips Judith of her illusions.

Nathaniel is the most obvious source of betrayal. He courts Judith with ambiguous attentions, leading her to believe in a future that never comes to pass.

When he chooses Alice instead, it is a public and devastating humiliation. Even worse, his marriage does not mark the end of his interest in Judith.

He returns, not to love her openly, but to use her in secret. His promises are hollow, his desire selfish.

Judith becomes a hidden part of his life, one he visits in moments of lust but never claims in daylight. His betrayal is not just sexual but spiritual.

He denies her dignity and makes her complicit in her own devaluation. This is compounded by Alice’s oblivious superiority and the community’s silent complicity in Judith’s marginalization.

Even the stranger, who offers something different, is ambiguous. While he never lies to her, his stories of werewolves and curses feel like riddles.

They force Judith to question reality itself. But unlike Nathaniel, the stranger never demands or deceives.

His betrayal, if it exists, is only in the ambiguity of his identity—not in the quality of his attention. Judith’s final realization comes when she sees how thoroughly she has been used.

Her dreams of love were not merely naïve but actively exploited. The wolf’s arrival crystallizes this understanding.

Rather than betray herself further by clinging to a false hope in Nathaniel, she redirects her allegiance to the unknown. Her choice is both an act of resistance and a tragic recognition of all that has been lost.

Transformation and the Monstrous Other

Transformation lies at the heart of this story, both literal and symbolic. Judith undergoes a profound metamorphosis.

It is not one marked by external changes but internal, psychological, and emotional ones. She begins as a quiet, obedient young woman living in the shadow of her sister and the dictates of a conservative village.

Her identity is tightly controlled by societal norms and familial roles. But as she engages in the affair and encounters the stranger, she begins to change.

The concept of the werewolf—the man who turns into a beast—is not merely myth in this story. It becomes a metaphor for freedom from constraint and for embracing primal truth over cultivated deception.

Judith is drawn to this idea, even as it frightens her. She sees in the stranger a life unbound by shame.

In his books and riddles, she glimpses a world where transformation is possible. Nathaniel, in contrast, represents stasis and hypocrisy.

He lives within the rules but breaks them in secret. He pretends to be noble while acting cruelly.

The beast, real or imagined, is the only figure who is honest about his nature. When Judith lets the wolf into the hut, it is the culmination of her psychological evolution.

She is no longer the girl who believed a spell could deliver love. She has shed that skin, like the stranger in his tales.

She has emerged into someone willing to accept the monstrous not as evil, but as a new version of truth. In choosing the wolf, Judith embraces change, wildness, and a future she controls—even if it lies beyond the human world.