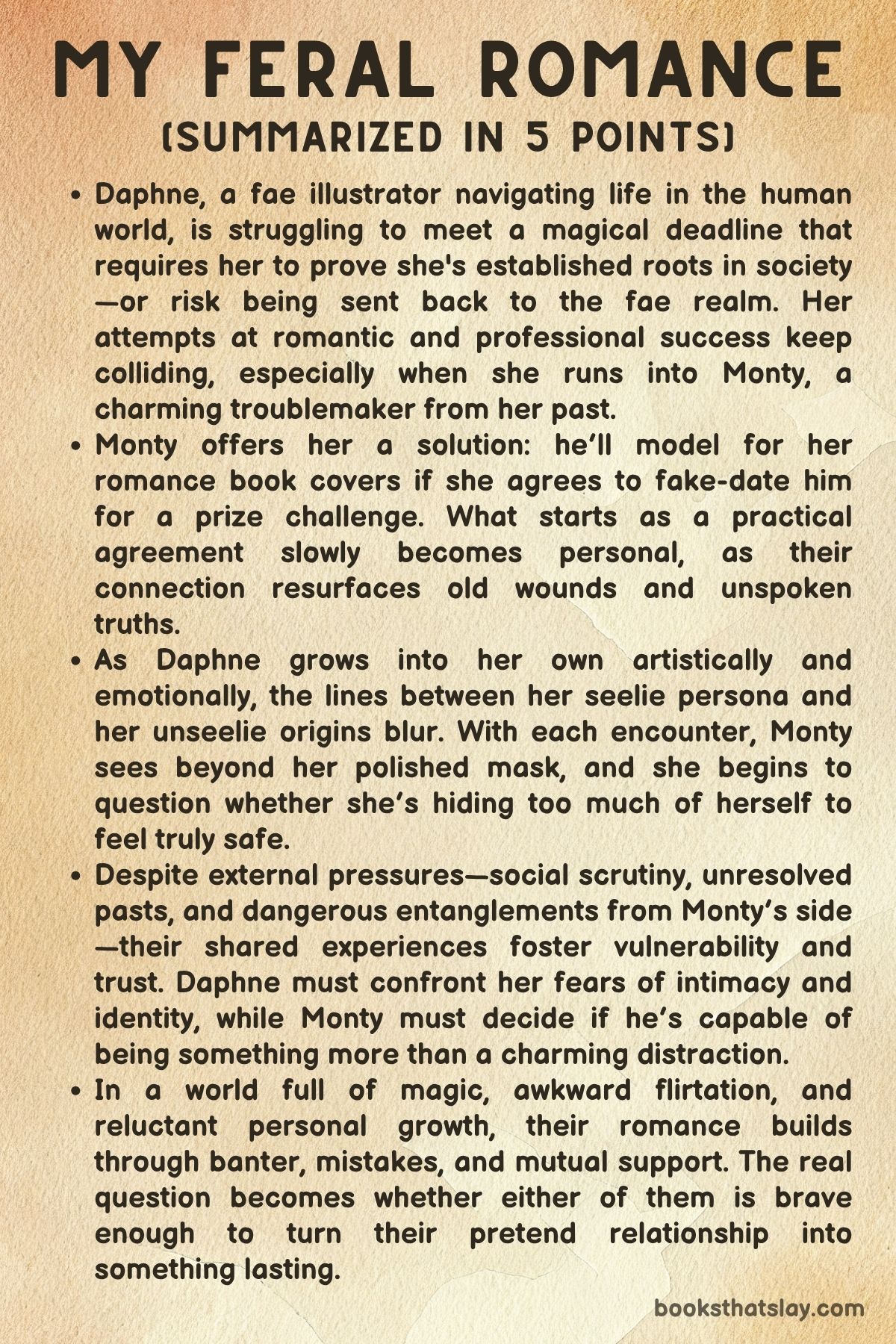

My Feral Romance Summary, Characters and Themes

My Feral Romance by Tessonja Odette is a uniquely charming romantic fantasy that explores the complicated terrain of self-worth, identity, and love through a fae-centered lens. With a voice that is at once witty, self-aware, and emotionally incisive, the novel follows Daphne, a pine marten fae navigating her human “seelie” form, and Monty Phillips, a roguish former aristocrat tangled in secrets and debts.

As their paths repeatedly intersect—first through workplace friction, then a shared artistic and emotional journey—they each confront their pasts and reimagine their futures. The narrative fuses romance, magic, and humor into a heartfelt tale of two people learning how to be seen, loved, and chosen on their own terms.

Summary

Daphne, a pine marten fae who must spend her days in her human-shaped “seelie” form, is trying to prove her worth at Fletcher-Wilson Publishing, where she often feels like an outsider. She takes her role seriously, always on guard, especially around Monty Phillips—an infuriating, flippant ex-aristocrat whose charisma masks chaos and vulnerability.

Monty, while seemingly careless, harbors his own burdens, and despite Daphne’s initial scorn, a complicated bond develops between them during a past book tour. That bond is tested when Monty disappears for a year and returns only to announce he has been fired for an impulsive and damaging interview.

A year later, Daphne struggles with a major illustration project—new covers for a bestselling romance series—only to discover that she can’t convincingly draw men. Her artistic block is tangled with deeper personal insecurities, especially her lack of romantic experience and her conflicted relationship with her body and desire.

A mischievous paper sprite named Araminta challenges and mocks her artistic efforts, eventually compelling Daphne to confront her fears and awkwardly ask a coworker to pose for her illustrations—and to marry her in order to avoid a magical binding ritual back in her hometown. The coworker’s rejection is witnessed by Monty, now returned with a hidden agenda and offering to help.

Monty is secretly pitching a relationship advice book, based on a pseudonymous column he writes, to secure a publishing deal that could save him from financial ruin. When he learns of Daphne’s dilemma, he suggests she observe models at an underground fighting ring.

They visit the clandestine venue together, where Monty is unexpectedly called to fight. His protectiveness erupts when an opponent insults Daphne, leading to a disqualification but also revealing his fierce loyalty.

In the aftermath, Daphne pleads with him to model for her. He agrees—but only if she agrees to be part of a case study for his book, testing out his romantic advice in real time.

Their agreement begins a mutual exploration filled with sensual tension, humor, and vulnerability. Monty poses shirtless for Daphne’s artwork, which becomes a safe space for both of them to express their feelings without fully acknowledging them.

When Daphne offers to expose herself to inspire his lustful expression for a scene, Monty halts her, but the gesture breaks down another wall between them. At the same time, Daphne reveals she is magically handfasted to a fae named Clyde—an obligation she wants to escape by either establishing her roots in Jasper or marrying someone new.

Monty, needing her to succeed for his own book deal, proposes a formal fae bargain: he will pose for each painting if she completes a romantic principle from his study.

As their pact continues, their emotional closeness grows harder to ignore. They travel to the grand Cyllene Hotel for a wedding, where Monty’s vulnerability deepens.

The setting triggers unresolved guilt and sadness tied to his strained friendship with Thorne, the groom, and his own fraught history. Daphne is a grounding force, interrupting his spiral with her trademark quirkiness and resilience.

One night, a romantic dance turns into a passionate encounter that nearly results in a kiss. Monty stops himself, citing the kiss as something that would make their relationship too real, drawing an invisible but undeniable line.

At the wedding reception, tension peaks. Daphne finds herself in the arms of another suitor, Patrick, while Monty watches from the sidelines, consumed by jealousy and doubt.

He tries to intervene, only to be stopped by Thorne. Overwhelmed, Monty retreats, and Daphne finds him outside, emotionally stripped bare.

He admits he cannot promise her the stability she needs—marriage, a future—though the longing between them is palpable. On the way back, both are quietly devastated.

Daphne begins to realize she loves him; Monty knows he already does.

Eventually, Monty invites Daphne to his apartment—a vulnerable act symbolizing his readiness to share not just space but truth. They talk openly about his past, his magical lineage, and the deep shame he carries over the volatile nature of his fire fae powers.

Daphne listens, accepts, and grounds him. Their emotional and physical union finally occurs, not just as a moment of passion, but as a genuine expression of love, trust, and mutual healing.

Monty then faces his domineering father, using legal leverage and hidden debts to sever the strings of manipulation that have controlled his life. For the first time, Monty stands fully in his own power, choosing love and integrity over legacy and expectation.

Meanwhile, Daphne is hit with professional sabotage when her artwork is censored by a Modesty Committee. She prepares to return to Cypress Hollow to dissolve her engagement to Clyde.

In a dramatic chase, Monty transforms into his unseelie fox form and tracks her to the train station to propose—but Daphne refuses to marry out of necessity. She chooses independence, renounces her Cypress Hollow citizenship, and makes a life-affirming decision to choose love and career on her own terms.

The couple travels together to Cypress Hollow, now in their true unseelie forms. There, Daphne discovers Clyde is already mated, freeing her from the magical bind.

After escaping the wrath of Clyde’s mate, Daphne and Monty embrace their freedom and each other in a moment of unity, desire, and clarity. Monty takes on the Heartcleaver name, signaling a new identity rooted in love rather than legacy.

A year later, they return to Jasper as a thriving couple—Monty an MMA fighter, Daphne a celebrated illustrator. Araminta, now transformed and with them, adds whimsy to their lives.

In a joyful twist, Monty proposes again—this time at a local festival—and Daphne accepts with genuine excitement. The book closes on a deeply emotional note as Monty is finally reunited with his long-lost mother, healing one final wound and stepping into a future filled with self-made love, freedom, and joy.

Characters

Daphne

Daphne, the protagonist of My Feral Romance, is a pine marten fae living in her human-shaped seelie form, grappling with the complexities of identity, creativity, and belonging. From the outset, she presents a voice laced with self-deprecating humor and a strong desire for professional success and social acceptance, especially as the only four-legged fae at Fletcher-Wilson Publishing.

Her need to conform underscores a deep vulnerability, driving her initial aversion to Monty’s chaotic presence and foreshadowing her journey toward self-acceptance. Daphne’s artistry—particularly her struggle to convincingly draw men—mirrors her emotional blockages and lack of romantic inspiration, highlighting how deeply intertwined her creative expression is with her personal evolution.

Her character arc unfolds in tandem with her romantic entanglement with Monty. As their interactions shift from antagonistic to intimate, Daphne’s guardedness begins to erode.

She exhibits resilience and humor in emotionally fraught situations—whether awkwardly propositioning a coworker or braving an underground boxing club. Her courage grows as she becomes more assertive, notably when she establishes the terms of her partnership with Monty or when she ultimately rejects a marriage proposal motivated by necessity rather than desire.

By the novel’s end, Daphne has undergone a remarkable transformation: from someone obsessed with control and appearances to a woman willing to shed her cultural identity, choose love on her own terms, and embrace her unseelie form with pride. Her arc is a rich portrait of a woman embracing vulnerability, artistic truth, and emotional courage.

Monty Phillips

Monty is a layered and charismatic figure in My Feral Romance, whose rakish persona masks profound emotional depth and personal turmoil. Initially introduced as a disruptive force in Daphne’s ordered life, he exudes irreverent charm and reckless confidence.

However, this surface-level flair conceals a troubled past, mounting debts, family trauma, and a deep-seated belief that he is undeserving of love or stability. His pseudonymous advice column—written as “Gladys”—offers glimpses into his genuine insight into romance, underscoring a contradiction between the persona he projects and the emotionally intelligent man beneath.

Monty’s character development is gradual and moving. His protective instincts surface during the boxing match when he defends Daphne’s honor, suggesting that his feelings run far deeper than casual flirtation.

His willingness to model for her, and to enter into a fae bargain that forces emotional proximity, reveals a man ready to confront his fears for someone else’s sake. The weekend at the Cyllene Hotel exposes his insecurities—particularly around fatherhood, friendship, and love.

His spiral after witnessing Daphne dance with another man shows how deeply wounded he is by his own perception of unworthiness.

The turning point in Monty’s journey comes when he invites Daphne into his modest home, stripping away the aristocratic pretenses and embracing a life of simplicity and truth. His honest confession about his dangerous magical lineage and his confrontation with his manipulative father signal a powerful reclaiming of agency.

By the end, Monty becomes a man no longer defined by shame or artifice but by courage, vulnerability, and love. His proposal—playful yet sincere—seals his transformation into someone worthy not just of Daphne, but of the life he once believed was out of reach.

Araminta

Araminta, the paper sprite-turned-companion, adds a sharply comedic and subversive edge to My Feral Romance. She begins as a sarcastic and biting side character, primarily functioning as Daphne’s artistic critic and occasional antagonist.

Her transformation into a humanoid figure and her persistent meddling in Daphne’s personal and creative affairs give her a dynamic presence that blurs the line between nuisance and confidante. Araminta’s barbed observations often push Daphne toward introspection, forcing her to confront truths she would rather avoid.

Despite her caustic manner, she consistently appears in moments of crisis, suggesting a deeper investment in Daphne’s well-being.

As the story progresses, Araminta’s character undergoes a subtle but significant evolution. Her presence at the underground boxing club, her commentary on Daphne’s romantic life, and her participation in the couple’s final trip to Cypress Hollow all point to a growing sense of loyalty and emotional complexity.

Her transformation at the end of the novel into a more permanent companion—perhaps even symbolically or magically reborn—mirrors the central theme of embracing one’s true form. Though not a romantic lead, Araminta represents the story’s emphasis on chosen family, loyalty forged through struggle, and the power of honesty delivered without sugarcoating.

Her final inclusion in the couple’s return home solidifies her role not just as comic relief, but as an integral figure in their emotional journey.

Clyde

Clyde is a peripheral yet pivotal figure in My Feral Romance, serving primarily as an obstacle to Daphne’s autonomy. As her magically handfasted fiancé—a commitment forged without her full consent—he symbolizes the suffocating expectations and archaic traditions of Cypress Hollow.

Though he appears mostly off-page, his presence looms over Daphne’s decisions, driving her need to secure a marriage or career that would dissolve their unwanted bond. When Daphne eventually returns to end the handfasting, Clyde’s revelation—that he is already mated—casts him as duplicitous, if not outright callous.

Clyde’s function in the narrative is to externalize the stakes of Daphne’s emotional and professional growth. His role underscores how fae customs can become tools of coercion and control, contrasting sharply with Monty’s insistence on mutual choice and consent.

While Clyde lacks the emotional nuance of the central characters, his final confrontation with Daphne and Monty cements the couple’s united front and affirms the novel’s broader themes of agency, self-definition, and chosen love.

Thorne

Thorne, Monty’s estranged friend, embodies the path Monty could have taken had he remained within the bounds of conventional success and social propriety. Now a settled man with a fiancée and adopted daughter, Thorne represents emotional stability, fatherhood, and the respectability Monty outwardly scorns but secretly longs for.

Their reunion at the Cyllene Hotel wedding stirs in Monty a painful cocktail of nostalgia, jealousy, and self-doubt. Thorne’s life is a mirror reflecting everything Monty believes he cannot have—and yet his very presence also propels Monty toward change.

Though Thorne plays a relatively minor role in the narrative, his influence is profound. His rebuke of Monty’s attempt to interfere during the wedding dance and his coldness toward Monty at key moments underscore the consequences of Monty’s past mistakes.

In this way, Thorne serves as a narrative fulcrum: a lost brotherhood that underscores the costs of Monty’s emotional walls and the stakes of failing to heal. He is a reminder that reconciliation, like romance, requires vulnerability, accountability, and time.

Angie (Angela)

Angela, Monty’s younger sister, appears as a background figure whose growth and strength quietly inspire Monty’s own transformation. Though not central to the main romantic plot, Angie serves as a moral compass and emotional anchor for Monty.

Her ability to rise above their family’s dysfunction and find personal success gives Monty a model of what is possible beyond their toxic legacy. His admiration for her fuels his determination to reclaim his life, fight his inner demons, and pursue Daphne with integrity.

Her symbolic function is crucial—she is proof that breaking away from generational trauma is possible. Monty’s reflections on Angie offer readers a glimpse into his capacity for familial love and remorse, adding depth to his character and affirming that change is not only desirable but achievable.

Angie’s impact is felt most strongly in Monty’s eventual confrontation with their father and his choice to build a life rooted in truth, not shame.

Monty’s Father

Monty’s father is a domineering and manipulative force in My Feral Romance, representing the patriarchal and hierarchical values Monty has spent much of his life fleeing. Cold, controlling, and obsessed with status, he uses secrets, debts, and family obligations to bind Monty to him, extending emotional manipulation into every facet of their relationship.

His grip over Monty’s life is insidious, culminating in the high-stakes confrontation at The Magnolia, where Monty finally breaks free.

The elder Phillips symbolizes the toxic expectations placed on fae aristocracy—expectations Monty ultimately rejects. His role in the novel is to crystallize the stakes of Monty’s growth: freedom must be seized, not given, and love must be chosen in defiance of inherited shame.

His defeat is not merely a plot resolution but a metaphorical death of the identity Monty had to abandon in order to live truthfully and love Daphne without constraint.

Themes

Identity and Self-Acceptance

Daphne’s journey in My Feral Romance is anchored in the complex terrain of identity, particularly as it relates to being a pine marten fae permanently transformed into a human-like seelie form. Her struggle is not merely about adapting to her altered appearance, but about reconciling internal perceptions with external expectations.

She tries to assert her place in the human-dominated environment of Fletcher-Wilson Publishing while masking her origins and downplaying what makes her different. Her inability to draw male anatomy convincingly is not just an artistic block—it reflects the disconnect between her self-image and how she navigates a world that marginalizes the animalistic side of her being.

Daphne is caught between longing for acceptance in the human world and maintaining fidelity to her fae heritage. This tension is aggravated by moments of perceived rejection—such as Monty calling her a “cute pet”—which reinforce the deep wounds caused by being reduced to a novelty rather than being seen as a full person.

The evolution of her identity is not linear but messy, filled with moments of humiliation, stubborn pride, and tentative courage. As she gradually reclaims her agency—refusing marriage as a means of escape, renouncing citizenship to make her own choices, and expressing her artistry without shame—Daphne finally begins to accept all aspects of herself, seelie and unseelie alike.

The culmination of this acceptance is evident in her willingness to return to Cypress Hollow not as an exile, but as someone determined to sever imposed bonds and reclaim her future. Her identity becomes a choice rather than a consequence, and that shift empowers her emotional and creative transformation.

Love, Vulnerability, and Emotional Risk

Monty and Daphne’s romance is not a straightforward union of opposites but an ongoing negotiation between attraction, emotional fear, and mutual need. Their relationship evolves under the weight of misunderstanding, unspoken desire, and buried emotional histories.

Monty’s charm and rakish exterior mask a depth of insecurity and trauma, including a complicated family legacy and a painful self-image. Daphne’s acerbic wit and drive for control are protective layers forged by years of exclusion and rejection.

When they begin their transactional arrangement—him modeling for her, her participating in his dating advice experiment—their interactions are tinged with hesitancy and unacknowledged intimacy. Moments such as Monty’s fight in the underground arena, his protective rage, or Daphne’s near striptease during a sketch session highlight how physical vulnerability becomes a stand-in for emotional expression.

As their relationship deepens, they each face the terrifying prospect of being truly seen. The slow progression toward love is shaped by restraint as much as it is by passion.

Even during their most physically charged encounters, both characters frequently pull back, afraid that acknowledging their feelings will rupture the careful balance they’ve maintained. Only when they shed pretense—Daphne accepting she doesn’t want a marriage of convenience, Monty confronting his fears of not being enough—does their love become real.

Vulnerability becomes not a liability but a path to mutual healing. Their eventual union, marked by transparency and emotional equality, is not the triumph of love over adversity, but love forged through the willingness to risk everything for truth.

Societal Pressure and Individual Autonomy

The world of My Feral Romance is governed not only by magic but by social constructs that dictate identity, obligation, and worth. Daphne’s experience with the handfasting ritual from Cypress Hollow, a magically binding engagement she wants desperately to escape, exemplifies the way societal expectations restrict personal freedom.

The cultural mandate to either marry or prove permanence through career highlights a rigid system where personal desires are subordinated to communal norms. Similarly, Monty’s history as an ex-aristocrat, forced to reckon with his father’s manipulative control and the pressures of reputation, reflects a different kind of social entrapment—one tied to lineage, status, and performance.

The Modesty Committee’s censorship campaign against Daphne’s workplace further emphasizes how institutional forces suppress creative expression and dictate moral boundaries. Both protagonists are, in their own way, clawing for freedom from systems that seek to define them.

Daphne chooses to reject the terms of her magical bond not through subterfuge, but by publicly renouncing her citizenship. Monty’s confrontation with his father is equally symbolic: he breaks generational ties, not with violence, but with strategic leverage that ensures he never has to be owned again.

Their joint decision to define their lives outside the parameters of fae tradition, professional roles, or aristocratic duty underscores the novel’s deeper commentary on autonomy. Love, in this narrative, is not just a personal emotion but a radical act of reclaiming the self in a world that constantly seeks to assign roles and extract conformity.

Artistic Expression and Emotional Honesty

Art is not just a career for Daphne; it is her language, her mirror, and her method of survival. Her initial inability to draw men properly, resulting in weasel-like caricatures, represents more than just a technical hurdle—it is a symptom of emotional repression and a lack of personal experience with desire.

Her growth as an artist parallels her emotional evolution. Each sketch session with Monty challenges her to confront not only the male form but her own reactions to intimacy, attraction, and self-worth.

When Monty agrees to model for her, the artistic process becomes a charged exchange—a test of boundaries and a catalyst for honesty. The turning point in her artistic confidence is not just about mastering anatomy but allowing herself to feel fully, to be unafraid of messy, overwhelming emotions that fuel genuine creativity.

Daphne’s private ballroom sketching session, the inspiration she finds in the magical hotel, and her eventual professional success all point to the idea that artistic breakthroughs cannot happen in emotional isolation. Art and truth are inextricably linked in the novel, and Daphne’s eventual freedom from censorship and professional constraint mirrors her emotional liberation.

By the end, she is no longer hiding her desires or sanitizing her expressions to fit into palatable molds. Her illustrations become vessels of authenticity—intimate, bold, and entirely her own.

The novel ultimately portrays creativity as an extension of the soul, one that flourishes only when honesty and vulnerability are allowed to exist without restraint or shame.

Transformation and Choice

Both Monty and Daphne undergo profound transformations, not as passive recipients of fate but as active agents confronting their pasts, fears, and desires. Monty’s arc is especially emblematic of the power of choice: once a self-destructive aristocrat drowning in debt and guilt, he becomes someone who finds dignity in simplicity, strength in transparency, and power in love.

His decision to reveal his painful magical lineage, to reject his father’s control, and to pursue a life aligned with his authentic values showcases a redemption rooted not in apology, but in agency. Daphne’s transformation, while different in origin, is no less significant.

Her shift from a cautious, approval-seeking illustrator to a confident, self-directed artist and partner reflects the internal work of rejecting fear-based decision-making. Her refusal to marry Monty out of necessity—even though she loves him—demonstrates her commitment to conscious, empowered choice.

The magical transformations that accompany their emotional growth—Daphne embracing her unseelie form, Monty adopting his fox persona to win her back—symbolize the shedding of false skins and the embrace of true selves. These transformations are not simply magical metaphors, but literal expressions of earned freedom.

Their decision to return to Cypress Hollow together, not as victims or fugitives but as equals, speaks to the novel’s insistence that freedom is not given, it is claimed. In choosing each other—and choosing themselves—they illustrate that transformation is not just about becoming something new, but about finally daring to be exactly who they are.