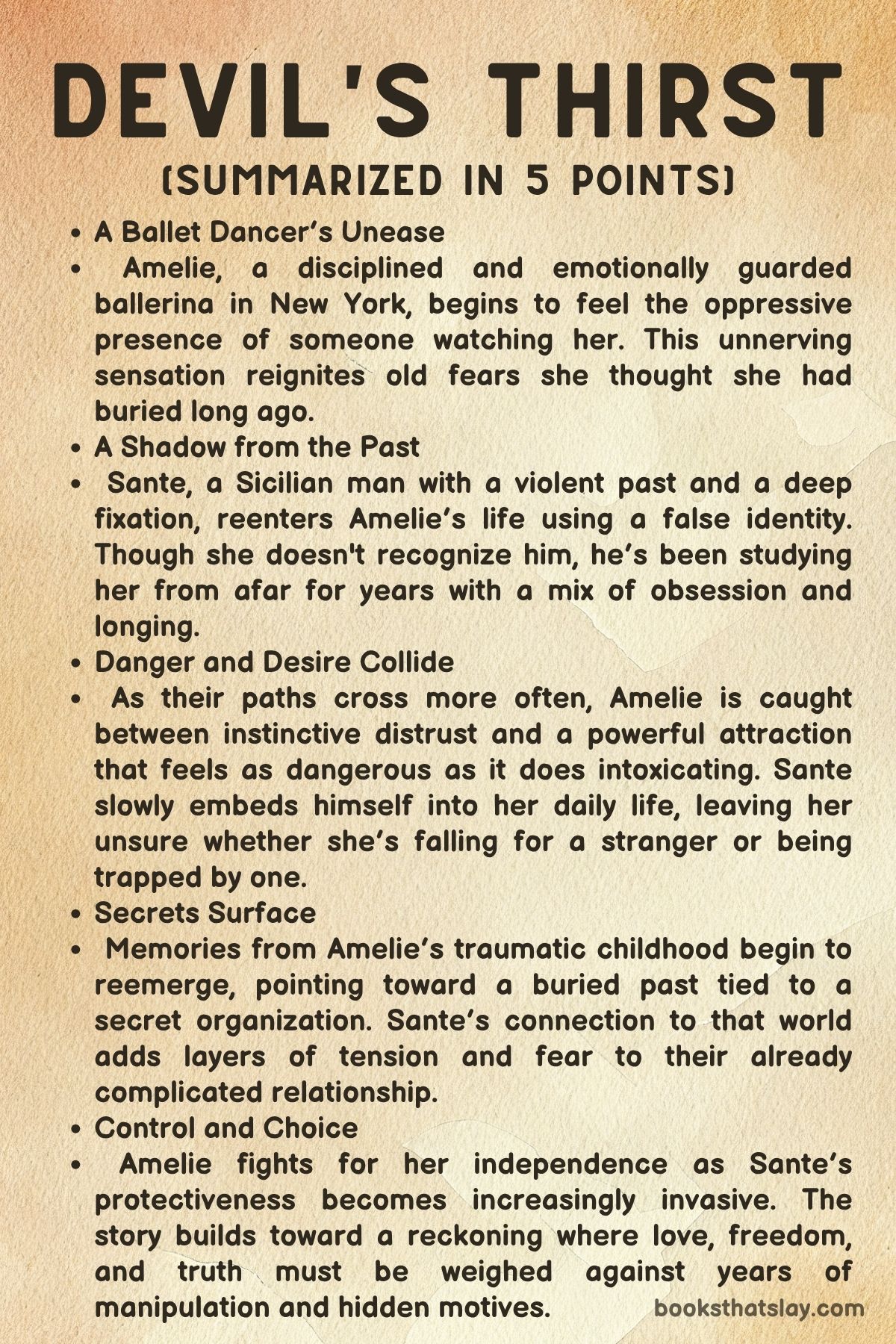

Devil’s Thirst Summary, Characters and Themes

Devil’s Thirst by Jill Ramsower is a dark, emotionally charged romantic suspense novel that explores themes of obsession, trauma, and healing through the story of Amelie Brooks, a gifted ballerina with a fractured past, and Sante, a man bound to her by a shared history and an all-consuming need to protect her. Told through alternating perspectives, the book immerses readers in a deeply personal struggle between danger and desire, where the boundary between love and control is never quite clear.

As secrets unravel and threats escalate, Amelie and Sante must confront their demons, challenge their fears, and decide whether their connection is a lifeline or a trap.

Summary

Amelie Brooks is a professional ballet dancer in New York whose life revolves around discipline, art, and a fragile sense of safety. Beneath her poised exterior, however, lies a haunting past marked by betrayal and trauma.

Her own parents once tried to sell her to a secret society for sexual exploitation. Though she escaped, the events left her with psychological scars and memory loss, forcing her to live with heightened vigilance and an ingrained distrust of the system, especially law enforcement.

Her carefully controlled world begins to unravel when she senses someone is watching her during her rehearsals. The feeling isn’t paranoia—it’s real.

The man watching her is Sante, who now goes by the alias Isaac. Four years earlier, he had known Amelie under entirely different circumstances, and despite trying to forget her, his obsession with her has only grown.

Initially, he intends to see her one last time, but upon laying eyes on her, he becomes completely consumed with the need to be near her, to protect her, and, in his mind, to possess her.

Isaac inserts himself into her life under the guise of coincidence. He moves into the apartment next to hers, stages encounters, and becomes a constant presence.

Amelie is disturbed by his intensity, but also captivated. Isaac’s presence is both alarming and magnetic—she senses danger but also feels drawn to his dominant energy.

Her instincts, sharpened by past trauma, warn her to be cautious, but her longing for connection overpowers her fear. When a masked stalker begins trailing her, Isaac becomes both a suspect and a potential savior.

The line between protector and predator blurs even further when he violently confronts and incapacitates the stalker, revealing his capacity for violence but also his unwavering focus on Amelie’s safety.

The story deepens as Amelie’s emotional world is further explored through her close relationship with her sister Lina and her niece Violet. These ties offer glimpses of normalcy and familial love, contrasting sharply with the sinister forces threatening her life.

Lina’s fatigue and stress add another layer of pressure to Amelie’s fragile world, highlighting her need to protect what little family she has left.

Isaac’s past comes into sharper focus as well. He was shaped by violence and survival in Sicily, raised by an uncle who taught him ruthlessness.

Now, his loyalty to Amelie is absolute. He confides in a friend, Tommy, about his plans, which are not spontaneous but calculated, driven by obsession and a distorted sense of destiny.

His desire for Amelie is matched only by his determination to destroy anyone who might harm her, including John Talbot, a powerful attorney general who once tried to buy her virginity and now uses a video of Lina’s sexual assault to blackmail them.

Amelie’s reluctance to go to the authorities stems from her fear of exposure and the failure of institutions that should have protected her. Isaac respects her fears and promises to wait before taking action, opting instead to work with his family and contacts in the Irish mob to gather information and build a plan.

Their alliance signals the scale of what they’re up against—corruption, organized crime, and a predator who believes himself untouchable.

The emotional and physical relationship between Amelie and Isaac evolves dramatically. While Isaac’s methods are aggressive and possessive, he is also acutely aware of Amelie’s trauma.

He uses intimacy as a way to offer her safety and control, introducing boundaries and gentleness in their private moments. Amelie, for her part, learns to surrender without fear, reclaiming her body and pleasure from the shadows of her past.

As their relationship intensifies, Isaac proposes marriage—not as a romantic gesture, but as a vow of permanent protection and commitment. Amelie accepts, seeing in him not just a lover, but an ally who believes in her strength.

However, the threats don’t end. Talbot’s presence looms larger when he shows up at Amelie’s opening night at the theater, triggering a visceral response.

Instead of running, Amelie finds her voice and, in front of a packed audience, names him as her rapist. The moment is transformative, a reclamation of power and a refusal to remain silent.

Her community rallies around her, and Officer Malone—one of the few trustworthy law enforcement figures—steps in to ensure Talbot is arrested.

Behind the scenes, Isaac ensures that Talbot’s arrest is more than symbolic. He interrogates and tortures Talbot to obtain confessions and verify the extent of his crimes, ultimately choosing not to kill him in order to honor Amelie’s wish for legal justice.

This restraint marks a turning point in Isaac’s journey—his ability to put Amelie’s needs before his rage.

The novel ends on a hopeful note. Amelie’s courage and public declaration mark the beginning of a new chapter.

Talbot faces multiple charges, and Amelie’s dance career continues to thrive. She and Isaac move forward with their marriage plans, surrounded by support and healing.

A final twist introduces a woman fleeing the Russian mob, hinting that the cycle of danger and redemption may continue in future installments.

Devil’s Thirst is ultimately a story about reclaiming agency in the face of overwhelming fear. Through love, loyalty, and the willingness to confront the darkest corners of their pasts, Amelie and Isaac forge a future neither thought possible.

It’s a raw, uncompromising exploration of how trauma lingers—and how, with the right kind of love, it can be faced and transformed.

Characters

Amelie Brooks

Amelie Brooks is a deeply layered and emotionally complex protagonist whose journey in Devils Thirst is both harrowing and empowering. A gifted ballet dancer, Amelie channels her passion and emotional burdens into her art, finding solace and control on the stage—a sharp contrast to the chaos of her personal history.

Her relationship with dance is more than professional; it is an act of reclaiming power over a life once marred by trauma, including a terrifying kidnapping and betrayal by her own parents, who tried to sell her into a shadowy secret society. These past horrors leave her perpetually on edge, oscillating between emotional repression and bursts of vulnerability.

Despite her apparent strength and self-reliance, Amelie is driven by a need for familial love and stability, as seen in her tender bond with her sister Lina and niece Violet.

What defines Amelie most, however, is her inner battle between fear and desire, particularly in her relationship with Sante (Isaac). She is at once terrified of and drawn to him, her instincts warning her of danger even as her body and heart gravitate toward the protection and power he offers.

This attraction often leads her to question her own sanity and motives, exposing the scars of her past abuse. Her eventual decision to trust Sante, even amid his possessive behaviors, marks a significant turning point in her character arc.

Through their evolving intimacy—particularly her first genuine experience of love and sexual agency—Amelie begins to heal and rediscover agency. Her decision to publicly expose her rapist, John Talbot, during a performance is the ultimate act of defiance and courage, signaling her transformation from victim to survivor, and from haunted girl to empowered woman.

Sante (Isaac)

Sante, known for most of the novel as Isaac, is an enigmatic and deeply conflicted figure whose presence electrifies every moment of Devils Thirst. He begins as a shadowy protector, driven by an intense obsession with Amelie that borders on dangerous.

His surveillance and orchestrated meetings are rooted in a twisted notion of love—one shaped by his own traumatic past in Sicily, where violence and survival were ingrained by his mob-connected family. Sante’s evolution from a brooding stalker to a fiercely loyal protector is gradual and fraught with contradictions.

While his actions often cross moral lines—moving into the apartment next to Amelie, secretly installing a tracker in her bracelet, and manipulating situations to assert control—his core motivation is to shield her from further harm, even if that means unleashing his own brutality.

The duality of Sante’s character is crucial. He is at once an agent of danger and a sanctuary from it.

His deepest desire is not just to possess Amelie but to become worthy of her trust and love. The revelation of his own family secrets and emotional wounds, including the shocking truth about killing his half-brother in a fatal altercation, humanizes him and highlights his emotional fragility beneath the exterior of dominance.

His sexual relationship with Amelie is equally complex, marked by dominance but carefully attuned to her trauma. He orchestrates experiences that give her power and pleasure, creating a space of consent and trust where fear once ruled.

Sante’s proposal and promise of lifelong protection mark his full transformation from avenger to partner, symbolizing a man who, despite his darkness, chooses to build a future with love as his compass.

Lina Brooks

Lina, Amelie’s older sister, is the moral anchor and familial core of Devils Thirst. Exhausted yet unwavering, she bears the burden of a shared traumatic past while trying to create a stable life for her daughter Violet and protect Amelie from the dangers that still loom.

As a survivor herself, Lina represents a different kind of resilience—one rooted in maternal strength, emotional fortitude, and sacrificial love. Her past includes a harrowing assault captured on video and used as leverage by John Talbot, yet she remains composed and fiercely protective.

Lina is the voice of reason when Amelie’s emotions threaten to spiral out of control, grounding her sister in moments of crisis and pushing her toward truth and justice.

Despite her own trauma, Lina encourages Amelie to pursue healing and take control of her story. When Amelie confesses the full extent of the blackmail and her past, Lina reacts not with pity but with resolve, standing as a pillar of support.

Her ability to face darkness without losing her empathy makes her not only a survivor but also a catalyst for Amelie’s transformation. Lina’s presence also highlights the enduring importance of sisterhood and how familial love can be both redemptive and empowering in the face of generational trauma.

Officer Malone

Officer Malone serves as a rare symbol of integrity and justice within the corrupt world depicted in Devils Thirst. Initially introduced as a cautious and mildly suspicious figure, Malone becomes increasingly significant as the story unfolds.

Unlike the system he operates within, Malone listens, observes, and ultimately acts on truth rather than power. His growing concern for Amelie’s safety and the strange dynamics surrounding her and Sante gradually shifts him from a passive observer to an active participant in seeking justice.

Malone’s pivotal moment comes when Amelie exposes John Talbot during her ballet performance. His response—intervening despite political pressure and facilitating Talbot’s arrest—proves that justice, though slow and often obstructed, is possible.

He symbolizes the necessary balance between vigilante justice, which Sante embodies, and lawful accountability, which Amelie ultimately chooses. Malone’s character provides a quiet but crucial counterpoint to the emotional volatility of Amelie and Sante’s world, reinforcing that systemic change can coexist with personal redemption.

John Talbot

John Talbot is the human face of the pervasive, insidious evil that haunts the world of Devils Thirst. A respected attorney general by day and a predator in the shadows, Talbot is the architect of the most devastating traumas in Amelie’s and Lina’s lives.

His attempts to purchase Amelie’s virginity and the recorded rape of Lina are not just acts of depravity, but symbols of the systemic abuse of power. He embodies a predator who operates with impunity, protected by societal status and institutional influence.

Talbot’s manipulations extend well beyond his crimes, using blackmail to silence and control his victims. Yet his downfall—precipitated not by force, but by Amelie’s brave public accusation—serves as a critical moment of justice.

Talbot’s arrest and impending trial not only mark a narrative victory but also serve as a thematic statement about truth, courage, and accountability. In many ways, Talbot is less a fully developed character and more a personification of the forces that try to suppress and exploit the vulnerable—a force that must be confronted for healing to begin.

Gloria

Gloria is a gentle yet formidable presence in Devils Thirst, offering emotional refuge and maternal warmth to Amelie when her world collapses. As a surrogate maternal figure, she provides what Amelie’s biological mother never could—unconditional love, compassion, and a safe place to land.

Gloria’s home becomes the emotional reset point where Amelie processes her trauma, regains her strength, and reaffirms her belief in the possibility of healing. Her nurturing presence contrasts starkly with the violence and tension surrounding Amelie, making her a symbol of healing through love and community.

Gloria also reinforces the theme of chosen family—those who provide safety and acceptance when blood relatives fail. Her belief in Amelie, combined with her unwavering support, helps fortify Amelie’s resolve to confront her past and embrace a future defined not by fear, but by love and empowerment.

Gloria may not be at the center of the action, but her role in the emotional landscape of the novel is both quiet and profoundly transformative.

Themes

Obsession and Possession

Sante’s fixation on Amelie in Devils Thirst transforms from a smoldering memory into a full-fledged obsession that drives the central dynamic of the story. His need to possess Amelie goes beyond mere attraction; it is a psychological imperative rooted in past trauma, grief, and unresolved identity.

His actions—moving in next to her, orchestrating “coincidental” encounters, tracking her movements, and gifting her a bracelet with a GPS—highlight a need for control masked as protection. Sante sees Amelie not just as a woman he desires but as a piece of his own fractured psyche, someone who validates his past and secures his emotional survival.

The line between obsession and devotion is deliberately blurred, challenging both characters and readers to question the nature of love that is so consuming it threatens to destroy the very person it cherishes. What intensifies this theme is Amelie’s response—she is alarmed but also drawn to it.

Despite sensing the danger, she cannot deny the comfort and erotic magnetism that Sante offers. The story refuses to simplify their dynamic into victim and predator.

Instead, it investigates how people marked by trauma sometimes crave the intensity of emotion that borders on unhealthy, especially when that intensity promises safety. Obsession in this novel is not a villain in itself, but a symptom of longing, loss, and a desire for permanence in a world that has shown both characters nothing but transience and betrayal.

Sante’s need to possess Amelie becomes a distorted path toward healing, challenging the reader to grapple with the ethics of love built on domination.

Trauma and Recovery

The emotional landscape of Devils Thirst is carved by the characters’ respective traumas—Amelie’s history of familial betrayal, sexual abuse, and near-trafficking, and Sante’s entanglement in violence, crime, and abandonment. Trauma is not background color in this story; it’s the central shaping force behind every decision, every hesitation, every connection.

Amelie’s reluctance to involve the police, her distrust of authority, and her need to maintain control over her narrative are all rooted in past violations that stripped her of agency. She has survived horrors not just in event but in memory—the fragmented recollection of a life-altering kidnapping and the betrayal of being offered up by her own parents.

Recovery for Amelie is fragile and nonlinear, often disrupted by panic, flashbacks, and dissociation. Her relationship with Sante becomes a crucible for both healing and re-injury.

Physical intimacy between them is not simply erotic; it is therapeutic and symbolic. Sante’s intentional slowness, his use of blindfolds, and his desire to reframe sex as something empowering for Amelie point to a conscious effort to rebuild what trauma shattered.

For Sante, recovery is tied to redemption. He believes saving Amelie is his penance, his way out of the moral purgatory he inhabits.

The story portrays trauma not as an individual affliction but as an ongoing negotiation between past harm and present hope. It is in moments of vulnerability, where Amelie confesses her history to Sante and later to her sister, that the narrative affirms healing is possible—not through avoidance or revenge, but through bearing witness, acknowledgment, and chosen vulnerability.

Power and Control

Control is a constant battleground in Devils Thirst—not just in overt confrontations but in the subtle negotiations of intimacy, identity, and autonomy. From the opening chapters, control defines how Amelie interacts with her world.

She dances alone, moves cautiously, and monitors her environment like someone accustomed to threat. Her hyper-awareness is a form of self-preservation, a way to reclaim the power she lost to past abusers.

Sante, by contrast, represents a different kind of control—external, dominant, and unrelenting. He exerts physical and emotional authority, but always cloaked in the language of care.

He doesn’t ask for entry into Amelie’s life; he creates situations where she has no choice but to let him in. His behavior flirts with coercion, yet his respect for her boundaries—when she clearly articulates them—is genuine.

Their evolving power dynamic complicates the theme: Amelie’s submission is never framed as weakness. Rather, it is depicted as a conscious decision, a way to experience vulnerability on her own terms.

When she asks Sante not to act impulsively against Talbot but to wait for a plan, it’s a pivotal moment of power redistribution. She asserts her voice, and he listens.

Their partnership begins to shift from dominance and surrender to mutual agency. Even in the realm of justice, Amelie insists on exposure over execution, affirming that true power lies not in destruction but in reclaiming narrative.

The novel ultimately suggests that control can be reconfigured as trust, but only when both parties consent to its terms and recognize each other’s sovereignty.

Family, Loyalty, and Protection

The question of who constitutes “family” and how loyalty manifests in the face of moral ambiguity pulses through every thread of Devils Thirst. Amelie’s biological family is a source of betrayal; her parents commodified her body and abandoned her humanity.

In contrast, her chosen family—her sister Lina, niece Violet, and surrogate maternal figure Gloria—offers a different, more nurturing framework. Loyalty in this circle is not passive; it is fierce, exhausting, and often painful.

Lina, herself a survivor of assault and blackmail, bears the psychological and physical burden of their shared past but never wavers in her love for Amelie. Their bond is a constant reminder that family is not defined by origin but by shared wounds and unconditional defense.

Sante’s loyalty is equally absolute, though rooted in darker soil. His protection of Amelie is wrapped in mafia tactics, surveillance, and veiled threats.

Yet the loyalty he shows is not performative—it is sacrificial. He’s willing to involve dangerous players, risk law enforcement scrutiny, and even restrain his desire for vengeance to honor Amelie’s wishes.

The loyalty he shows to his own family—revealing truths about his half-brother’s death and enduring his uncle’s abuse—shows that for him, protection is not a choice but a code. The novel situates loyalty as both a weapon and a balm, capable of either escalating conflict or facilitating healing.

In a world where institutions fail and blood betrays, the fierce, often unspoken loyalty among these characters becomes the only stable ground on which they can build futures.

Justice and Exposure

Amelie’s confrontation with her abuser, Talbot, crystallizes a complex exploration of justice in Devils Thirst—not as retribution but as reclamation of truth. For much of the story, legal systems are viewed as tools of the powerful.

Talbot, a public figure with a dark past, manipulates legal structures to silence and control his victims. Amelie’s initial avoidance of the police stems from this very imbalance—she has been burned by the justice system and fears it will protect her predator more than her.

But the arc of her character shifts when she chooses not to seek revenge but public truth. By standing on stage and announcing Talbot’s crimes, she reframes justice as visibility.

It is a radical, public act of defiance that asserts control over her narrative. This is not justice via courts or violence, but through collective witnessing.

Her courage inspires institutional action: Officer Malone’s intervention is a sign that justice may yet be possible within the system, but only when individuals dare to force it to reckon with uncomfortable truths. Sante’s initial instinct is violent retaliation, but he honors Amelie’s request, channeling his rage into careful planning and evidence collection.

He enacts a form of vigilante justice that ultimately supports her broader aim of dismantling Talbot’s power legally. The novel positions exposure—not annihilation—as the ultimate punishment.

By stripping Talbot of anonymity and influence, Amelie robs him of his greatest weapon: silence. Justice here is not punitive alone; it is transformational, making space for survivors to speak and for systems to change.