Gabriel’s Moon Summary, Characters and Themes

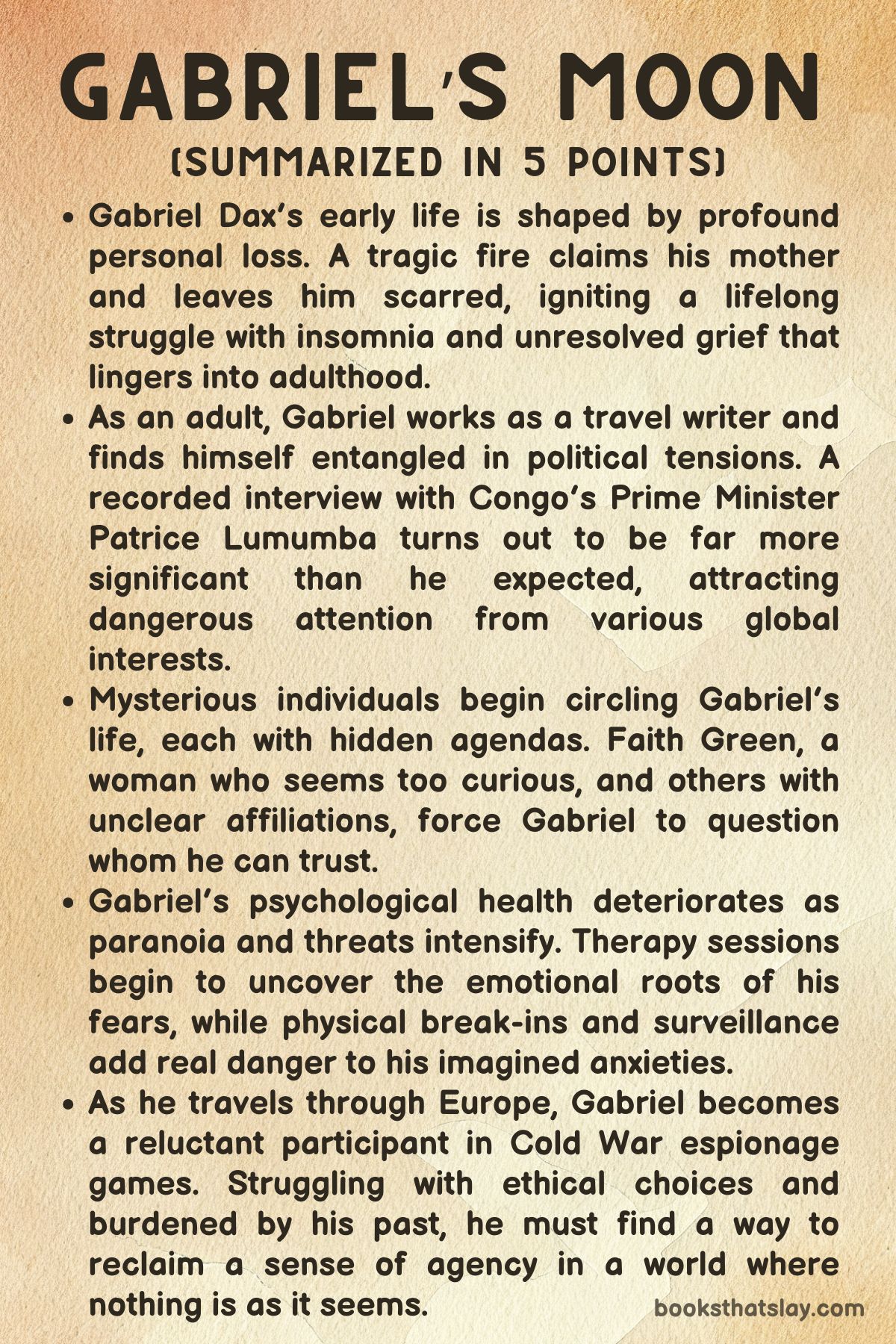

Gabriel’s Moon by William Boyd is a sweeping Cold War-era novel chronicling the life of Gabriel Dax, a travel writer who becomes a reluctant operative in the world of espionage. The story opens with the haunting trauma of Gabriel’s childhood and evolves into a complex exploration of identity, memory, and manipulation within global intelligence networks.

Through intersecting relationships, missions, and betrayals, Boyd constructs a psychological portrait of a man caught between personal history and political agendas. As Gabriel traverses cities and allegiances, he seeks clarity amid uncertainty—trying to understand not just those around him, but also the ghost of himself that trauma and secrecy have created.

Summary

Gabriel Dax’s earliest memory—of a glowing glass “moon” lit by his mother before bed—is interrupted forever by the fire that destroys his home and takes her life. That formative loss, imprinted with fire and silence, becomes a cornerstone of his psychological development, plaguing him with insomnia and nightmares.

Raised alongside his older brother Sefton, Gabriel grows up disconnected and restless, eventually shaping a career as a travel writer. Yet the role offers little escape from the emotional fractures of his youth or the looming shadow of international politics.

While in the Congo during the turbulent period after independence, Gabriel interviews Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, capturing the fears and threats surrounding the leader’s final days. But his editor buries the story, citing its irrelevance in the wake of a coup.

The erasure of his work and the hints of larger forces at play begin a pattern that will define Gabriel’s adult life: truth suppressed, loyalty questioned, and meaning obscured.

Back in London, Gabriel notices strange intrusions into his life. Silent phone calls, altered arrangements, and repeat encounters with a woman named Faith Green suggest surveillance.

Faith, elegant and calculating, claims to work for an innocuous research institute—but her true role within the British intelligence service becomes increasingly clear. She offers Gabriel a small task: to travel to Spain and purchase a drawing from a surrealist artist named Blanco.

The simplicity of the mission masks a deeper web of manipulation, but Gabriel, intrigued by Faith and perhaps craving significance, agrees.

His brother Sefton, whose civil service role is deliberately vague, also hints at favors he can pull, blurring the line between familial support and governmental exploitation. Gabriel’s bond with Sefton is strained—resentment, rivalry, and secrecy run deep between them.

In Spain, under the pretense of being an art dealer, Gabriel completes the mission, but is left unsettled. At Café Gijón, he hands the drawing to Kit Caldwell, a charismatic MI6 station head and former lover of Blanco.

The delivery is successful, yet Gabriel realizes how little he understands of the scheme’s true purpose.

Gabriel’s relationship with psychoanalyst Dr. Katerina Haas adds another dimension to his search for understanding.

Her guidance leads him to reexamine his trauma, personal relationships, and even his sexual and class identities. Her insistence on “anamnesis”—the excavation of memory—helps him see the connections between his emotional instability and childhood loss.

Yet even Haas is not who she seems; her credentials are falsified, further reinforcing Gabriel’s disorientation.

The emotional narrative threads intertwine with escalating espionage. Gabriel is asked by a fan, Nancy-Jo, to carry a package home.

Suspecting a setup, he opens it to find heroin and discards it. Later, Nancy-Jo confesses she was coerced into manipulating him by an American agent named Raymond Queneau.

Her sudden death—overdose or murder—intensifies Gabriel’s distrust.

The political stakes sharpen with the revelation of the “Las Monteras Incident”—a supposedly lost hydrogen bomb recovered and tampered with in Spain. Gabriel learns from Caldwell that this was an orchestrated deception by MI6 and the CIA to mislead the Soviets about Western nuclear capabilities.

Embedded in this plot are drawings by Blanco, embedded with microdots—miniaturized intelligence hidden in artwork. These are being used to feed misinformation to the KGB.

Gabriel, unknowingly, has served as a courier for one of these encoded pieces.

In Cádiz, Blanco offers Gabriel a secret in exchange for money: Caldwell is planning to defect to the Soviet Union. Shocked, Gabriel passes the information to Faith but soon changes his mind and warns Caldwell instead, helping him escape aboard a Polish freighter.

His decision—a blend of moral rebellion, loyalty to a friend, and rejection of the machinery around him—sets off a political firestorm. The British government downplays Caldwell’s defection, while Gabriel is left to wonder about the consequences of his interference.

Haunted by betrayal, Gabriel begins tracking Faith, eventually confronting her in Southwold, where their ambiguous relationship turns briefly intimate. Faith confesses fragments of her wartime torture but offers no solace or clear allegiance.

Her past, like everyone else’s in the intelligence world, is steeped in ambiguity. Gabriel’s obsession with her deepens, reflecting both attraction and revulsion.

The final section returns to Warsaw, where Gabriel discovers the truth behind the microdot operations and his manipulated role. Caldwell—still loyal to the West—has been using the drawings to disseminate false information to the Soviets.

Queneau, the CIA agent, reemerges on a ferry with intent to kill Gabriel. In a rare moment of instinctive violence, Gabriel shoots him, disposing of the body and crossing a moral line he never imagined.

Sefton’s involvement also reaches its climax. As Gabriel learns of his brother’s deeper ties and eventual exposure as a Russian mole, he warns him obliquely.

Soon after, Sefton dies by suicide—an act of either guilt, fear, or preemptive control. Faith confirms Sefton’s treachery, but her tone remains detached.

Gabriel’s guilt over his role in Sefton’s death further blurs his ethical compass.

Even as Gabriel tries to pull away, he remains ensnared. A Russian cultural attaché later hands him a book stuffed with money, an indirect signal that he has become a handler, or at least a link in the espionage chain.

Gabriel hesitates, but does not reject it outright. His entanglement is complete—both used and complicit.

In the novel’s final moments, Gabriel seeks refuge in writing, returning to his identity as an observer, but now forever altered. He is no longer merely a travel writer nor a passive participant.

His sense of self is fractured, floating between the romanticism of loyalty, the burden of complicity, and the exhaustion of moral ambiguity. Gabriel’s Moon ends not with resolution but with reflection, leaving Gabriel suspended in the murky space between personal truth and historical manipulation.

Characters

Gabriel Dax

Gabriel Dax is the central figure in Gabriel’s Moon, a character whose life is profoundly shaped by trauma, paranoia, and existential searching. From childhood, Gabriel carries the emotional scars of witnessing his home burn down and his mother perish in the flames, a memory that spawns his chronic insomnia and a deep-rooted distrust of permanence and safety.

This early loss sets the tone for his identity as a restless, emotionally guarded adult. As a travel writer, Gabriel operates on the fringes of global events, always in motion but never truly at rest, a vocation that mirrors his inner dislocation.

Thrust into the world of espionage, he becomes a reluctant pawn in a complex Cold War game involving MI6, the CIA, and KGB operatives. His journey is as much psychological as it is geopolitical.

Gabriel is repeatedly manipulated—by Faith Green, by his own brother Sefton, by Kit Caldwell, and even by Nancy-Jo—and these betrayals gradually erode his idealism. Yet he remains intellectually acute and emotionally searching.

Through psychoanalysis, particularly under the influence of Dr. Katerina Haas, Gabriel attempts to excavate his past and reconstruct a coherent self.

His relationships, from romantic entanglements to sibling rivalry, all reflect his yearning for authenticity in a world riddled with deception. By the novel’s end, Gabriel has evolved into a more complex, morally ambiguous figure—haunted but no longer naïve, resigned to a compromised role within the espionage machine even as he struggles to maintain his personal ethics.

Faith Green

Faith Green is one of the most enigmatic and commanding figures in Gabriel’s Moon, a woman who embodies the duplicity and allure of intelligence work. Initially introduced as an alluring stranger who reads Gabriel’s book on a plane, she later emerges as an MI6 handler and key player in the clandestine operations that define Gabriel’s life.

Faith is cold, calculating, and fiercely competent, yet her mask occasionally slips to reveal a deeply scarred individual shaped by her own experiences of wartime torture and survival. Her strategic brilliance lies in her ability to manipulate others while maintaining an aura of plausible deniability.

She never shows her full hand, ensuring that everyone—including Gabriel—remains one step behind her. Even her fleeting moments of vulnerability, such as her sexual encounter with Gabriel or her revelation about past trauma, seem strategically timed.

Faith’s power lies not only in her professional role but in her psychological dominance. For Gabriel, she represents both fascination and threat—a symbol of the unknowable, and perhaps unattainable, woman who orchestrates his descent into the spy world.

By the conclusion of the novel, Faith remains elusive, a shadowy architect of events who controls narratives from behind the scenes, offering glimpses of humanity only when it suits her aims.

Sefton Dax

Sefton Dax, Gabriel’s older brother, operates as a spectral force throughout Gabriel’s Moon, embodying the shadow of governmental power and familial ambivalence. Though outwardly portrayed as a minor civil servant in the Foreign Office, Sefton is ultimately revealed to be a deeply embedded operative entangled in Cold War espionage.

His relationship with Gabriel is marked by a blend of condescension, strategic kindness, and latent rivalry. Sefton’s true allegiance becomes one of the novel’s central mysteries, and his identity as a Russian mole—confirmed only after his suicide—casts a retroactive light over all his previous actions.

His manipulation of Gabriel under the guise of familial concern exemplifies the theme of personal betrayal. Despite his distant and sometimes chilly demeanor, Sefton’s final moments hint at guilt and recognition of the trap he has lived within.

His death, possibly catalyzed by Gabriel’s subtle warning, becomes a devastating emotional blow to his younger brother. Sefton represents the tragic cost of secrecy and double lives—an embodiment of how Cold War ideologies fractured even the most intimate human bonds.

Kit Caldwell

Kit Caldwell is a charismatic and conflicted MI6 station chief whose journey from allegiance to defection complicates the moral terrain of Gabriel’s Moon. Initially introduced as a suave, well-connected operative with a history of bisexual relationships—including a romantic past with the artist Blanco—Caldwell serves as both mentor and cautionary tale for Gabriel.

His presence is compelling, exuding charm and mystery, and he quickly becomes a symbol of the moral grey zones of espionage. Caldwell’s apparent defection to the Soviet Union shocks Gabriel, but even this betrayal is later recast as a complex double-cross.

His true loyalties remain murky, and he ultimately reveals that the entire operation involving the microdot drawings was part of an elaborate deception against the KGB. Caldwell’s manipulation of Gabriel is less cruel than Faith’s but equally exploitative, cloaked in friendship and shared understanding.

He is the tragic embodiment of a world where loyalties shift, and truth is always provisional. His final appearance, orchestrated through cryptic messages and a cultural attaché, cements his status as a master manipulator and a figure whom Gabriel can neither fully condemn nor admire without reservation.

Nancy-Jo

Nancy-Jo is a deceptively gentle presence in Gabriel’s Moon, whose innocence belies her instrumental role in the larger espionage drama. Introduced as a sweet, somewhat daft American who idolizes Gabriel, she quickly becomes a figure of suspicion when she attempts to use him as a drug mule.

Though she initially appears to be a casual acquaintance or admirer, Nancy-Jo’s story takes a darker turn when it’s revealed she has been coerced by a CIA agent known as Raymond Queneau. Her growing affection for Gabriel, or perhaps guilt over her actions, leads her to confess, which tragically culminates in her suspicious death.

Whether she is murdered or overdoses remains uncertain, reinforcing the novel’s theme of blurred realities. Nancy-Jo’s arc captures the vulnerability of individuals caught in the crossfire of global intelligence games.

She is a victim rather than a player, and her fate adds emotional weight to Gabriel’s growing disillusionment with the machinery he’s become entangled in.

Katerina Haas

Dr. Katerina Haas serves as Gabriel’s psychoanalyst and a symbolic guide through the labyrinth of his own psyche in Gabriel’s Moon.

Though later exposed as not being a licensed doctor, Haas is instrumental in helping Gabriel confront the repressed trauma that has shaped his life. She introduces him to the concept of anamnesis—the recovery of forgotten or hidden memories—encouraging him to excavate the emotional wreckage of his childhood.

Haas’s therapeutic sessions with Gabriel are pivotal, not only for his psychological development but also for exposing his internal conflicts around identity, class, and sexuality. Her questionable credentials and eventual deception mirror the larger themes of false appearances and hidden agendas.

Yet, paradoxically, her insights are among the most truthful elements in Gabriel’s journey. Haas exemplifies the moral ambiguity of healing in a world where even therapy can be a front.

Her character blurs the line between charlatan and savior, reflecting the broader instability of truth in both personal and political realms.

Blanco

Blanco, the surrealist artist and brother of Inès, is a peripheral yet crucial figure in Gabriel’s Moon, representing the intersection of art and espionage. Initially presented as a reclusive genius, Blanco is eventually revealed to be instrumental in the dissemination of microdot intelligence embedded in his artwork.

His eccentricity masks a sharp political awareness, and his decision to participate in the MI6 ruse adds a new layer of meaning to the artistic process. Blanco’s ambiguous sexuality, his connection to Caldwell, and his nonchalant attitude toward espionage deepen his mystery.

He challenges the traditional role of the artist, using creativity as camouflage for subterfuge. In doing so, Blanco becomes a symbol of how truth and illusion, beauty and deceit, can exist simultaneously in both art and politics.

Raymond Queneau

Raymond Queneau, the alias of a deadly CIA operative, operates largely in the shadows of Gabriel’s Moon, but his impact is significant. He embodies the lethal extremities of Cold War intelligence operations—a man who uses charm and coercion in equal measure.

His manipulation of Nancy-Jo, his surveillance of Gabriel, and his eventual attempt to kill him place Queneau at the narrative’s most dangerous margins. Despite limited direct interaction, his presence looms large, culminating in a chilling confrontation aboard a ferry that forces Gabriel to commit murder in self-defense.

Queneau’s death marks a definitive moral shift for Gabriel, transforming him from reluctant participant to someone capable of lethal action. Queneau represents the ruthlessness of the American intelligence machinery and underscores the novel’s unflinching depiction of espionage as a realm where humanity is expendable.

Themes

Trauma and Memory

Gabriel Dax’s life is shaped by an early trauma that leaves a profound and lingering impact. The fire that claims his mother’s life not only physically displaces him but psychologically destabilizes his sense of safety, identity, and continuity.

This event becomes the nucleus of his emotional disorder, manifesting in chronic insomnia, recurring nightmares, and an inability to sustain intimacy or peace. Rather than being a resolved incident of childhood, the fire becomes a living presence in Gabriel’s adult psyche, resurfacing in both literal flashbacks and symbolic repetitions of betrayal and chaos.

His sessions with Dr. Katerina Haas expose the fractured scaffolding of his memory, prompting him to explore “anamnesis” as a means of reconstructing repressed experiences.

Memory in Gabriel’s Moon is not static or reliable—it is haunted, evasive, and dangerous. Gabriel’s attempt to piece together the truth about his mother’s death parallels his broader struggle to understand his place in a reality distorted by lies, secrets, and performances.

Whether through his recollection of the Lumumba interview or the veiled history of intelligence missions, Gabriel is perpetually surrounded by half-truths. The novel positions trauma not only as a source of personal suffering but as an access point to a deeper awareness of the world’s duplicity.

The very act of remembering becomes a radical assertion of autonomy in a landscape where deception is endemic. Gabriel’s journey toward psychological coherence is incomplete and faltering, but the narrative affirms the necessity of confronting pain to reclaim agency, even when the truth offers no comfort.

Espionage and Moral Ambiguity

The world Gabriel navigates is structured by espionage but defined by a relentless erosion of moral clarity. He is repeatedly drawn into clandestine missions under the guise of simplicity—purchasing a drawing, delivering a parcel, attending meetings—only to discover these gestures are weighted with implications he only understands in retrospect.

Gabriel is not a trained agent, yet he becomes a vessel for misinformation, a courier for state secrets, and a tool of powerful institutions that shield their actions in layers of abstraction. The intelligence community in Gabriel’s Moon is not populated by clear-cut heroes or villains; instead, it is a realm of pragmatism and betrayal, where alliances shift and ethics are expendable.

Faith Green and Kit Caldwell embody this ambiguity: Faith is brilliant, composed, and brutally manipulative, while Caldwell’s supposed defection is a calculated ruse designed to mislead the Soviets. Gabriel’s complicity deepens when he chooses to help Caldwell escape, not out of ideological conviction but loyalty and emotional allegiance.

This choice echoes throughout the narrative, especially when Gabriel kills Queneau—an act that marks his transformation from a passive participant to an active, morally compromised survivor. The espionage in the novel is not glamorous; it is isolating, disorienting, and corrosive.

The boundaries between truth and deception collapse under the weight of statecraft and psychological manipulation, leaving Gabriel—and the reader—to question whether any action in this world can be considered unambiguously right or wrong. Through this theme, the novel critiques the romanticization of spycraft and instead exposes it as a mechanism of control, exploitation, and existential uncertainty.

Identity and Self-Construction

Gabriel’s arc is fundamentally a search for identity, complicated by the roles he is forced to assume. From travel writer to accidental agent, from traumatized son to reluctant killer, his life is defined less by his choices and more by the roles imposed upon him.

The identities he inhabits—fabricated personas for espionage, social disguises to navigate class and romantic boundaries, or psychological masks to suppress trauma—create a fragmentation that leaves him unsure of who he truly is. Even his relationship with his brother Sefton, cloaked in competition and suspicion, mirrors this crisis of identity.

Sefton appears to be a civil servant but is revealed to be a Russian mole; Gabriel, the observer, becomes the focal point of international interest without ever seeking such attention. The world continually attempts to define Gabriel, but none of these definitions seem to fit.

His romantic and sexual encounters also contribute to this search: Lorraine represents a possible escape into simplicity, while Faith embodies the seductive allure of complexity and danger. Each of these relationships reflects a different facet of Gabriel’s internal schism.

His writing, once a medium for exploration and self-expression, becomes yet another tool used against him. Only at the end, when he receives the book filled with money from the Russian attaché, does he confront the stark reality that even his most basic identifiers—writer, Briton, brother—have been compromised.

In this way, Gabriel’s Moon becomes a meditation on the instability of the self in a world determined to manipulate, categorize, and exploit it.

Power and Manipulation

Power in Gabriel’s Moon is not overt or institutional—it is psychological, covert, and often invisible until it has already been exerted. Gabriel is not simply caught in the web of espionage but in a constant interplay of control and submission, orchestrated by characters who know more, reveal less, and act with impunity.

Faith Green is perhaps the most emblematic figure of this dynamic. Her ability to compartmentalize intimacy and ruthlessness reflects a model of power that operates beyond traditional authority.

She recruits, seduces, punishes, and withholds—all while maintaining plausible deniability. Even when Gabriel confronts her, she retains the upper hand, leaving him with truths so carefully framed that they act as traps rather than revelations.

Caldwell, too, manipulates Gabriel, enlisting his loyalty without ever fully disclosing the stakes. Sefton’s final actions—his suicide and hidden allegiance—reveal how manipulation corrodes familial bonds, turning love and trust into liabilities.

The systems Gabriel interacts with—the Institute, MI6, the CIA—are shown to manipulate individuals not for any moral good but for strategic advantage. Even therapy, a supposed site of healing, becomes suspect when Gabriel learns Haas lied about her qualifications.

The novel suggests that manipulation is endemic to systems of power, which rarely present themselves as coercive but always operate as such. Gabriel’s resistance is fragmented and reactive; he pushes back when he can, but often too late.

The final gesture of accepting the money-laden book, though morally fraught, signals his recognition that power can no longer be escaped—it can only be navigated with awareness and wariness.

Disillusionment and Existential Drift

By the end of the novel, Gabriel Dax exists in a state of existential drift, unmoored from his past certainties and future ambitions. The world he once believed in—defined by rationality, personal relationships, professional integrity—is systematically dismantled.

His attempts to find meaning in work, love, or ethics repeatedly fail. Writing, once a passion, is weaponized.

Love is either transactional or a mask for ulterior motives. Loyalty results in death or betrayal.

The defection plot, which momentarily offers Gabriel a sense of purpose, ultimately reveals itself as another manipulation in a long line of stratagems. Even his act of killing Queneau—a moment of supposed agency—brings no catharsis, only deeper ambiguity.

Gabriel’s sense of disillusionment is not merely with institutions or individuals but with the very possibility of moral coherence. He no longer knows what is right or who to trust, and worse, he recognizes that such clarity may never be possible.

The Cold War backdrop intensifies this feeling, presenting a world governed by opaque allegiances and cynical realpolitik. The only recourse left to Gabriel is partial withdrawal: he returns to his flat, contemplates solitude, and tries to resume writing.

But even this retreat is marked by compromise. He accepts the Russian attaché’s book, knowing full well its implications.

Rather than a grand conclusion, the novel ends with a quiet unraveling—a man walking through a world he no longer understands, hoping that introspection and isolation might offer a semblance of control. This final note of existential drift makes Gabriel’s Moon a deeply human story about survival in a morally fractured world.