Sweet Vidalia Summary, Characters and Themes

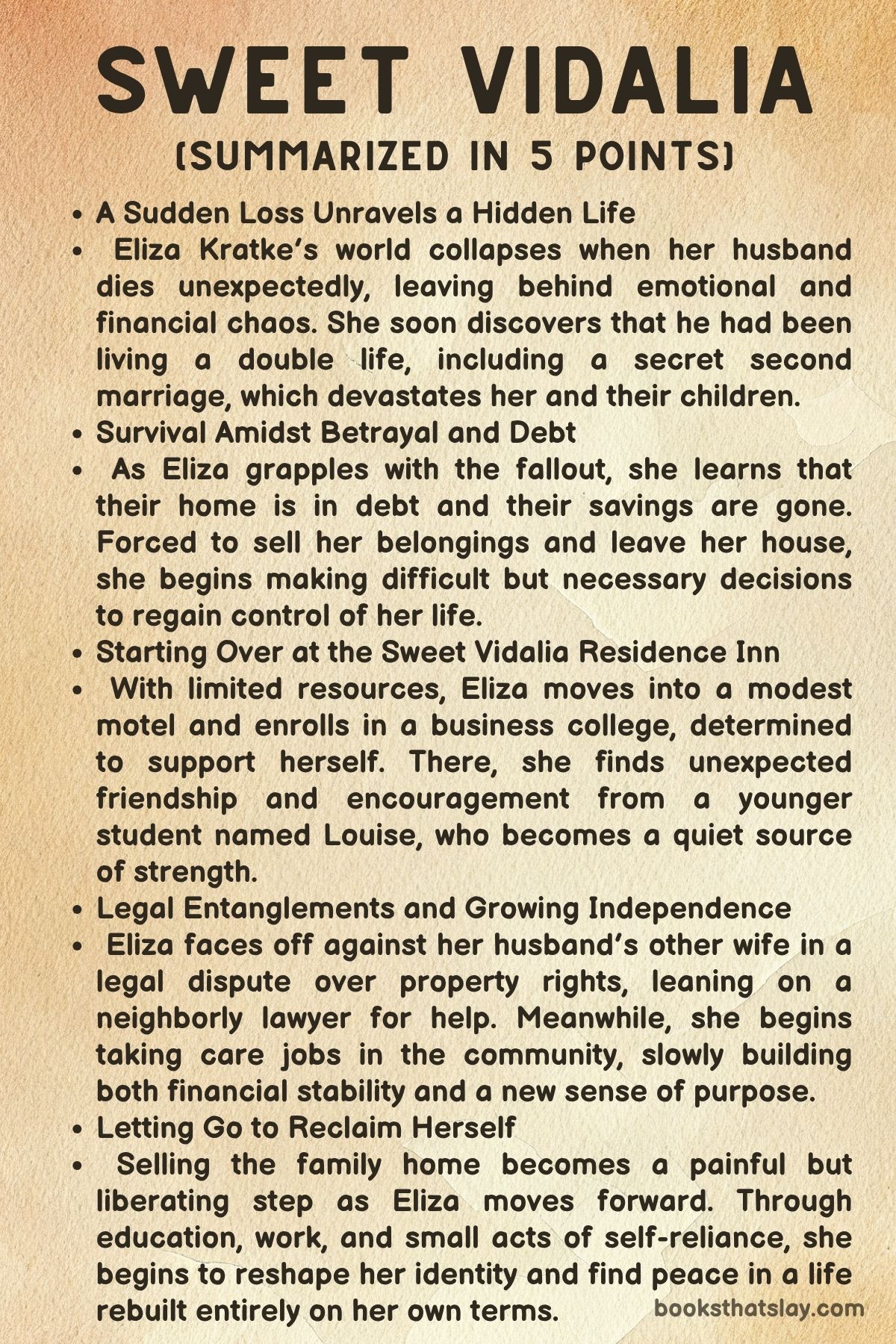

Sweet Vidalia by Lisa Sandlin is a quiet but powerful character study of a woman forced to rebuild from the ruins of her life after betrayal, loss, and financial devastation. Set in 1960s Texas, the novel follows Eliza Kratke as she navigates the aftermath of her husband’s sudden death, only to discover that he lived a double life and left her with crippling debt.

Through a series of subtle, often symbolic events—selling her belongings, taking business classes, finding companionship in unlikely places—Eliza transforms from a shocked widow into a quietly determined survivor. It is a story of reinvention, courage, and self-possession born of necessity.

Summary

Eliza Kratke’s story begins on an ordinary February day in 1964, disrupted by the sight of her husband, Robert, in visible distress. Though no words are spoken, their long-honed nonverbal understanding pushes her into action.

She drives frantically to the hospital, ultimately delayed by a police officer who misreads the urgency. By the time she reaches help, Robert dies in her arms, leaving behind not only grief but also an unfinished confession that haunts Eliza.

His last gaze, filled with unsaid truths, plants the seeds of unraveling.

Robert’s death cracks open Eliza’s reality. While her children gather around her in mourning, practical concerns quickly take precedence.

She learns that Robert emptied their savings and took out a second mortgage on the house. Initially, she imagines gambling or a financial mistake, but the shock deepens when she discovers another woman claiming to be Robert’s wife.

This woman, June Kratke, not only shows up at the funeral but also later asserts a legal claim on the house. The betrayal hits harder than the financial ruin.

Eliza’s dignity remains outwardly intact, but inside, she is adrift.

When creditors attempt to repossess Robert’s prized Fairlane car, Eliza takes matters into her own hands. She cleans and polishes the vehicle and, using quick thinking and nerve, sells it to a buyer before the creditors can get to it.

This act marks the beginning of her taking control. One by one, she sells off furniture and family heirlooms.

She faces her daughter Ellen’s rage and pain with stoic grace, recognizing that she cannot fix the emotional damage but can offer presence and resilience. Eventually, she signs away the house, both a financial necessity and an emotional severing from the life she once had.

June Kratke’s legal claim puts a lien on the house, turning it into a site of conflict. Eliza contemplates burning it down, but instead burns the collection letters in her backyard—a symbolic gesture of rage and refusal.

With legal help from her neighbor Earl Fitzwalter, she negotiates the murky waters of ownership. To keep her independence, she rents out the house and moves into the modest Sweet Vidalia Residence Inn, telling her children she’s going to Houston to spare them worry.

Her new home, a tiny motel room with a kitchenette, recalls a childhood fantasy of a playhouse—symbolizing both isolation and autonomy.

Her move is marked by indignities. Taxi drivers refuse her aging dog, Percy, and a young man helps only by sneaking the dog in a paper bag.

The motel is a step down, but Eliza maintains control through strict budgeting and stoic self-sufficiency. She enrolls in business courses at Carlton Business College, where she is the oldest student.

She befriends Louise, a brash young woman with a limp and a gift for drawing, who becomes an unlikely ally. Louise’s quirky brilliance and backwards-written notes help Eliza navigate her classes.

To support herself, Eliza begins doing laundry for younger tenants, despite her arthritis. She meets Ike, a barefoot college student who gives her herbal remedies and emotional support without judgment.

The friendship is gentle and healing. Morton, a mysterious man who walks dogs and rarely speaks, becomes another quiet fixture in her life.

On Thanksgiving, Eliza travels by bus to Houston. A teenage girl gives birth on the bus, and Eliza offers her tablecloth for the newborn.

The experience is raw and surreal, linking her emotionally to the girl’s struggle and evoking memories of her own early days with Robert.

Her visit with her son Hugh and daughter-in-law Pam is tinged with melancholy and tension. Pam’s mother makes subtle jabs, and Eliza is reminded of the missing pieces of her life—most notably, her daughter Ellen’s absence.

She returns to the Vidalia to find Louise gone and Morton’s room burglarized. Eliza learns that Morton is a writer, and the revelation sparks dormant dreams.

She reclaims her maiden name, Brock, a quiet but powerful assertion of self.

Louise resurfaces with a dangerous secret: she’s been involved in a counterfeiting operation. The box she always carried contains printing plates for fake money.

Eliza, who once defended her to Louise’s pursuer—Ray Paley, Louise’s father—gets questioned by federal agents. She is detained and fingerprinted, but maintains composure, denying knowledge of the crime.

Her resolve remains intact, though she is visibly shaken.

In jail, she meets Faye McKnight, a woman whose blasé attitude and kindness force Eliza to confront how far she has fallen. Eliza breaks down in the cell but also opens up, sharing her dreams and hardships.

The connection with Faye becomes a strange form of clarity. Ray Paley secures her release and offers her a job at his collection agency.

There, Eliza proves herself capable and organized, earning the respect of hardened men like Red, who had once repossessed her car. She takes on fieldwork, handling repossession with empathy rather than aggression, and often finds ways to help those she’s sent to confront.

Her bond with Mrs. Mavis Jordan, an elderly woman facing relocation, becomes another testament to Eliza’s quiet compassion.

When Mavis is moved to a nursing home, Eliza continues visiting and eventually purchases the old woman’s house. It becomes her own—not a return to the life she lost, but the beginning of a new one built on earned peace.

In the final moments, Eliza confronts June and secures the quitclaim deed, allowing her to finally sell the house and close that chapter. She removes her wedding ring, a symbolic act of closure.

Though the pain of Robert’s betrayal and the loss of her dog Percy remain, Eliza embraces the life she has built: modest, self-sufficient, and authentically hers. Amid wild hedges and birdsong, she discovers not happiness, but contentment, and a resilient form of freedom grounded in uncertainty and hard-won grace.

Characters

Eliza Kratke (later Eliza Brock)

Eliza stands at the center of Sweet Vidalia, undergoing one of the most profound character evolutions in recent literary fiction. Initially presented as a devoted wife and mother, her life is shattered by the sudden death of her husband, Robert, and the avalanche of betrayals that follow.

What begins as a quiet, domestic grief transforms into a deeply psychological unmooring, as Eliza discovers Robert’s financial mismanagement and his bigamous secret life. Yet, she does not collapse.

Her initial shock gives way to fierce pragmatism: selling a car to outmaneuver creditors, shouldering the pain of her children, and beginning the painful process of severing her past. Her decision to remain in Bayard, despite pretending to move away, signals a complex pride and a fierce need for self-preservation.

Living at the Sweet Vidalia Residence Inn, working menial jobs, and attending business school all mark her descent into a spartan life, but also her climb toward self-definition. Her relationships—with Louise, Ike, Morton, and later Terry—bring warmth and complexity, showing Eliza’s ability to connect, protect, and grow even when life demands secrecy and sacrifice.

By the novel’s end, Eliza has reclaimed her maiden name, forged a career, faced legal injustice, and negotiated with her late husband’s other wife with grace. Her trajectory, from fragile grief to quiet authority, forms the emotional and thematic core of the narrative.

Louise

Louise is one of the most enigmatic and symbolically rich characters in Sweet Vidalia. Introduced as an eccentric, sarcastic, and strangely brilliant young woman with a limp, she initially appears to be comic relief, a chaotic foil to Eliza’s reserved nature.

However, Louise quickly proves to be a character of layered contradictions. Her friendship with Eliza is unpredictable but deeply affecting, marked by spontaneous generosity—such as giving away her notes written in mirrored script—and volatile absences.

Louise embodies the instability of youth and the burden of hidden truths, and as her story unfolds, the extent of her secrets becomes dangerous. Her involvement in counterfeiting and the presence of printing plates in her duct-taped box reveal a shadow life of risk and recklessness.

Yet even as she pulls Eliza into legal jeopardy, Louise remains strangely sympathetic—a girl with talent, pain, and perhaps no one to look out for her. Her reappearance after being gone and the brief protection Eliza offers her suggest a surrogate maternal bond, fractured but real.

Ultimately, Louise represents both the fragility and recklessness of marginal youth, and the ambiguous moral spaces women often navigate when survival is at stake.

Robert Kratke

Though Robert dies in the book’s opening pages, his spectral presence haunts nearly every moment of Eliza’s transformation in Sweet Vidalia. In life, he was a man of quiet routine and apparent stability.

In death, he is revealed as a fraud—a man who not only bankrupted his family but maintained another life with a second wife, June. This revelation shatters Eliza’s image of her marriage and introduces the book’s central theme of betrayal.

Robert’s character becomes a palimpsest: each memory of him is overwritten by Eliza’s newfound knowledge. The brief, cryptic moment before his death—when he looks at Eliza as if trying to tell her something—becomes a psychological hinge, a silence loaded with guilt and withheld truth.

His legacy is not one of love, but of unraveling: financial wreckage, familial alienation, and emotional devastation. And yet, his impact is complex.

He pushes Eliza, in absence, to build her identity from ruins. He is the ghost that demands she live a different life.

In this way, Robert is less a character and more a haunting force of contradiction, failure, and reluctant catalyst for his wife’s emancipation.

Earl Fitzwalter

Earl, the lawyer-neighbor who quietly steps in to help Eliza navigate the legal nightmare of Robert’s betrayal, serves as one of the novel’s few dependable male presences. He is competent, discreet, and deeply respectful of Eliza’s dignity.

His willingness to work for barter—accepting her mahogany breakfront instead of legal fees—speaks to his understanding of both her pride and desperation. Earl is not romanticized; he delays paperwork, and his help isn’t always swift.

But his presence provides Eliza with a kind of ethical grounding. He believes in her capacity to manage on her own terms and aids her without condescension.

In a story rife with deceitful or absent men, Earl offers a quiet counterpoint—an example of masculine support rooted in respect rather than control.

Terry

Terry, Eliza’s flamboyant and witty classmate at Carlton Business College, adds both levity and pathos to the narrative. As a skilled but marginalized gay man, he shares with Eliza the struggle for dignity in a world that devalues them based on age, gender, or sexuality.

Their friendship is grounded in mutual resilience. They share jokes, support each other through job disappointments, and offer a model of platonic intimacy forged in shared rejection.

When Terry lands a job interview only because Eliza gives up her own opportunity, it’s a quiet testament to her generosity and their bond. Terry’s story arc—ambiguous success, enduring friendship, quiet perseverance—mirrors Eliza’s in miniature.

Together, they form a unit of solidarity, pushing back against societal erasure with humor, skill, and care.

Morton

Morton, Eliza’s reclusive neighbor at the Sweet Vidalia, emerges as one of the book’s quieter but more profound companions. Initially a strange man with dogs, he is eventually revealed to be a writer, a revelation that elevates his role from odd neighbor to kindred spirit.

His gentle care for Percy and his willingness to watch over the dog during Eliza’s trip to Houston show his capacity for quiet kindness. His own vulnerability—evidenced when his apartment is broken into—parallels Eliza’s precarious state.

Morton offers Eliza not romance, but something more sustaining: mutual recognition. Their bond is one of two solitary people who, having been wounded, find solace in small acts of companionship and shared quiet.

Ray Paley

Ray Paley, introduced as a collection agent and Louise’s estranged father, initially appears adversarial, but his role evolves into something more complex. He arranges Eliza’s release from jail and hires her at Paley and Associates, a company embedded in the rough world of debt collection.

Ray is gruff, often critical of Eliza’s softer approach to repossession, but he respects her work ethic. His interactions with Louise are tense and ambiguous, suggesting a deep familial fracture filled with regret and distance.

Ray functions as a bridge between two of the novel’s moral spheres: the punitive, capitalist world of collections and the ethical, humanistic realm Eliza strives to inhabit. Their professional relationship is uneasy but productive, marking another step in Eliza’s slow reclamation of power.

Faye McKnight

Faye McKnight appears briefly but makes a deep impression during Eliza’s night in jail. Her casual camaraderie, her unfazed attitude about incarceration, and her simple gestures of kindness shake Eliza from despair.

Faye treats Eliza not as a woman fallen from grace, but as one among many women who have been bruised and betrayed. Her acceptance and curiosity open a door for Eliza’s self-reflection.

Faye’s character, though peripheral, underscores the theme that human connection can arise in the bleakest spaces, and that healing often begins in unexpected companionships.

June Kratke

June, Robert’s other wife, is an antagonistic yet tragic figure. Her claim to the Kratke home after Robert’s death throws Eliza into legal turmoil and further emotional devastation.

June is portrayed as unhinged and desperate, filled with rage and bitterness, yet her pain is undeniably real. She, too, has been deceived by Robert, though her reaction is consumed by entitlement and hysteria.

When Eliza confronts her to secure the quitclaim deed, June lashes out, not just out of legal defensiveness but from deep personal betrayal. Their confrontation serves as a final exorcism of Robert’s shadow.

June’s presence in the narrative cements the idea that betrayal reverberates across lives, and that women—pitted against each other by male deceit—must find separate paths to healing.

Mavis Jordan

Mrs. Mavis Jordan, the elderly woman Eliza meets during her repossession work, becomes a beacon of unexpected emotional depth.

Forgetful, lonely, and often lost in reverie, Mavis evokes Eliza’s longing for continuity, connection, and purpose. Their relationship is one of gentle mutual care.

When Mavis is moved to a nursing home, Eliza continues to visit her, and eventually buys her old house. This gesture is not only an act of compassion but a reclaiming of domestic space on Eliza’s terms.

Mavis, like Morton and Faye, represents the peripheral souls who offer Eliza quiet insight, reminding her that dignity can be found even in forgotten places and people.

Themes

Betrayal and the Shattering of Illusion

The emotional core of Sweet Vidalia rests on Eliza Kratke’s confrontation with the unbearable truth of betrayal by the man she trusted most. Robert’s sudden death leaves behind not only financial disarray but also a secret life with another wife, June.

What begins as confusion around bank accounts and mortgage documents soon escalates into a complete dismantling of Eliza’s marriage. This betrayal reverberates through every facet of her life: her children’s sense of identity, the home they believed to be theirs, and Eliza’s entire framework of memory.

Rather than reacting with immediate rage or drama, Eliza absorbs these blows with an eerie quiet, which reflects the internal rupture that defies articulation. Her identity, once securely tethered to wifehood and homemaking, is pulled into question.

She begins to understand that she was living within a façade, where even the simplest memories carry the weight of falsehood. This theme becomes more than the shock of infidelity—it is about how betrayal corrodes trust, dignity, and personal history, forcing the betrayed to question not only the betrayer but themselves.

Eliza’s gradual, restrained processing of the truth reflects how betrayal doesn’t always erupt; sometimes it settles like dust, covering every object in the home, every remembered conversation, every holiday. Her subsequent actions—selling the car, signing away the house, burning letters—are small rituals in the emotional reordering that betrayal demands.

They are not acts of vengeance, but of necessity, as Eliza must clear out not only physical remnants of Robert’s deception but also the emotional framework he occupied.

Resilience and the Quiet Rebuilding of Self

Eliza’s trajectory is marked by a stubborn, humble commitment to surviving with dignity. After the foundation of her life collapses, she does not retreat into self-pity or melodrama.

Instead, her resilience expresses itself in small but powerful acts: haggling for a better price on a car, cleaning rooms, doing laundry, registering for business classes. These gestures are not dramatic rebirths but deliberate steps toward self-definition.

In her move to the Sweet Vidalia Residence Inn, Eliza accepts a radically reduced lifestyle not as defeat but as a form of self-protection and liberation. Her dignity is tested repeatedly, from being denied taxi service because of her dog to the indignity of being fingerprinted after Louise’s counterfeiting scandal.

Yet her response is rarely reactive; instead, she cultivates a sense of patience, practicality, and personal order. Even her pride—often a mask for grief—becomes a tool for survival, enabling her to hide her financial desperation from her children.

In many ways, her resilience lies in embracing control over the little she has left. Her decision to reclaim her maiden name is not a loud declaration but a quiet repositioning of self.

She does not fantasize about triumph or revenge. What she wants is basic: control over her finances, ownership over her days, and the freedom to exist on her own terms.

Her resilience does not erase her pain, but it allows her to live alongside it with grace.

Female Solidarity and Unexpected Community

Throughout her descent into social and financial obscurity, Eliza finds unexpected lifelines in the form of other women—and occasionally men—who extend empathy, camaraderie, or sheer eccentricity. The bond between Eliza and Louise begins on shaky ground, rooted in shared displacement in a classroom of younger students.

Louise’s defiance of social norms and her unconventional intellect become a mirror through which Eliza views her own untapped boldness. This unlikely friendship is not simply generational contrast; it is a testament to the healing power of interdependence among women who are marginalized in different ways.

Similarly, Faye McKnight’s kindness in jail—a roll of toilet paper, a casual conversation—offers Eliza a glimpse of unpretentious, unjudging sisterhood in the most humiliating of circumstances. These moments suggest that solidarity does not have to be grand or righteous; it can be grounded in momentary empathy, in knowing glances or unspoken understandings.

Even her fleeting connection with Mrs. Jordan, an aging woman discarded by society, adds another layer to this theme.

Eliza does not abandon Mrs. Jordan after her relocation but visits her and ultimately purchases her home, preserving both a memory and a relationship.

These connections stand in contrast to the duplicity of her marriage, creating a new framework of trust and intimacy. The narrative resists presenting these bonds as purely redemptive.

They are flawed, interrupted, sometimes suspicious—but they are real, born from shared vulnerability rather than idealized alliance.

The Cost and Value of Independence

Eliza’s journey toward autonomy is filled with sacrifices, both material and emotional. Her choice to remain in Bayard rather than burden her children in Houston is as much about pride as it is about love.

Her independence is not a simple gain; it is purchased with isolation, reduced comfort, and persistent anxiety. At the Vidalia Inn, she is surrounded by strangers, bound by silence and routine.

The space she inhabits is small and sometimes demeaning, but it is hers. Her financial independence comes with physical strain—doing laundry despite arthritis, negotiating legal help with household furniture, managing a budget down to the penny.

The irony is sharp: in fleeing from dependency, she enters a form of deprivation, yet feels a growing sense of ownership over her time and choices. Her job at Paley and Associates, though morally complicated, furthers this theme.

She earns her keep, negotiates ethical grey areas, and reshapes how she is perceived by others—not as someone to be pitied, but as someone to be respected. Yet this independence is not framed as triumphant.

It is lonely, often unacknowledged, and deeply exhausting. Still, it is chosen.

Eliza’s final acts—removing her wedding ring, buying a home with her own earnings, tending to her new garden—are quiet victories. They do not erase what she has lost but affirm what she has built.

Her independence is not about freedom from others but the freedom to define herself without lies, compromise, or dependency masked as devotion.

Memory, Grief, and the Rewriting of Personal History

Eliza’s grief is not just for the death of Robert but for the life she thought she had. Every memory becomes suspect, every gesture between them tainted by the knowledge of Robert’s duplicity.

The story forces her to reconstruct her personal history, not through nostalgia, but through skepticism and painful honesty. She recalls moments that once seemed innocuous—a trip, a conversation, a bill—now filtered through the lens of betrayal.

This psychological unmooring reflects how grief can fragment not just the present but the past. The Thanksgiving visit to her son’s house magnifies this theme.

The missing tablecloth becomes a stand-in for all the domestic certainties she no longer possesses. Her reflection on the birthing scene on the bus also ties memory to transformation—what once would have been a horrifying ordeal becomes a defining event, reaffirming her role as a witness, a helper, someone essential.

Even her relationship with Percy, her old dog, becomes entwined with memory and loss; his eventual death is another tether severed. Eliza is constantly weighing what to carry forward and what to let go.

She doesn’t bury the past, but she reorganizes it. Reclaiming her maiden name is part of this reconfiguration—not to disown who she was, but to honor the parts of herself that existed before the marriage.

This thematic focus on memory reveals how identity is never fixed, especially after trauma. To grieve is not only to mourn what was lost but also to reexamine what was real.

Through this painful but necessary process, Eliza moves toward a more honest understanding of her own story.