The Case of the Missing Maid Summary, Characters and Themes

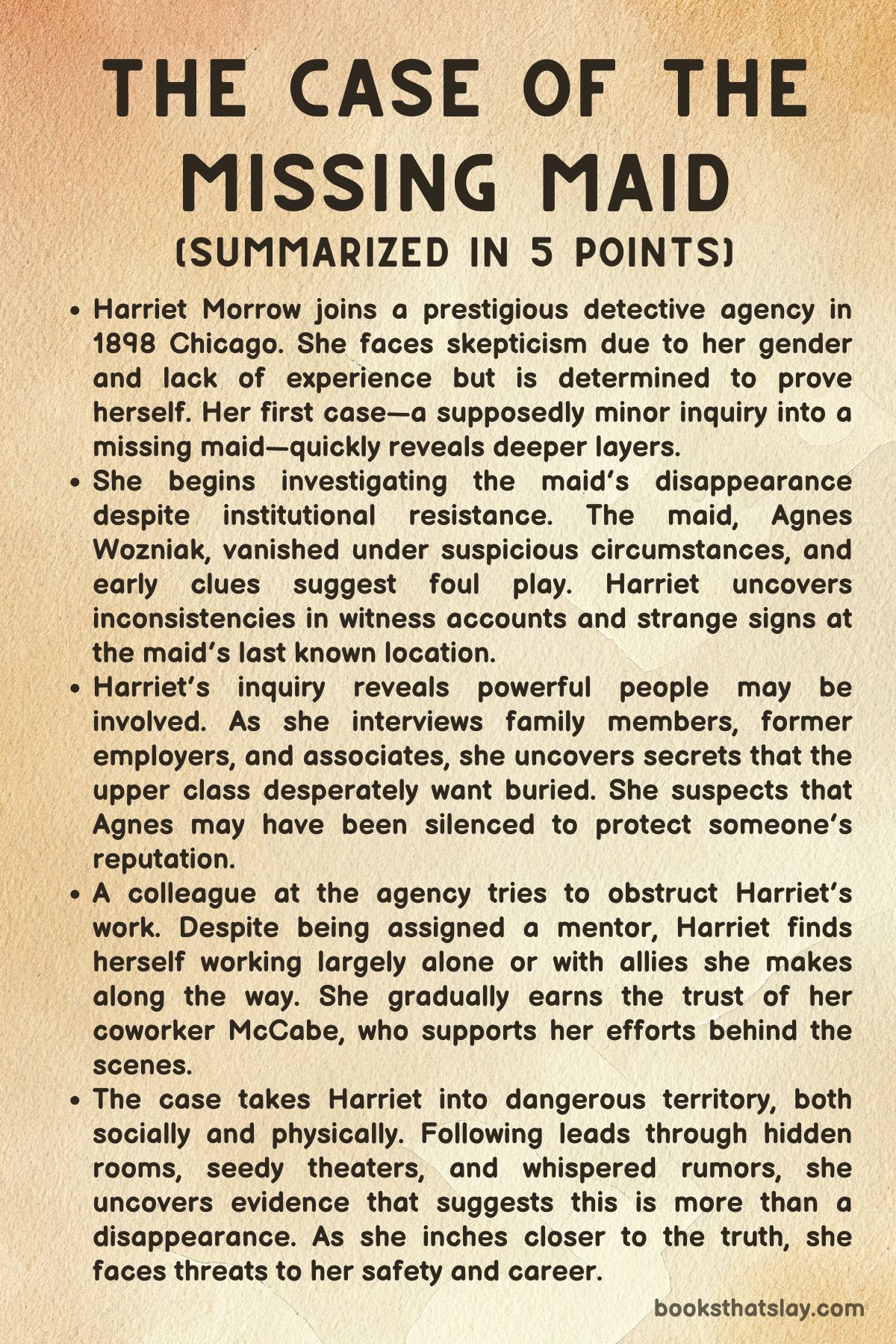

The Case of the Missing Maid by Rob Osler is a historical mystery set in 1898 Chicago, following Harriet Morrow, a pioneering young woman determined to succeed as the city’s first female detective. In a time when gender roles are rigid and opportunities for women are limited, Harriet challenges conventions with her masculine attire, keen intellect, and unwavering ambition.

As she investigates the disappearance of a maid, Agnes Wozniak, Harriet must navigate institutional sexism, social stratification, and personal sacrifice. This debut novel offers not only a compelling mystery but also an inspiring portrait of a woman who refuses to conform, choosing integrity and courage over societal approval.

Summary

In The Case of the Missing Maid, Harriet Morrow steps into the world of private investigation with unflinching confidence and a sharp eye for detail. In 1898 Chicago, she joins the prestigious Prescott Agency as its first female detective, despite the skepticism and outright dismissal she faces from the agency’s staff.

Harriet dresses in masculine clothing, favoring practicality over societal norms, a choice that underscores her commitment to her principles. Her arrival at the agency is met with resistance, especially from Madelaine and the receptionist, who refuse to believe a woman could be hired for such work.

Only Mr. Prescott’s confirmation silences their doubts.

Harriet’s first assignment is to investigate the disappearance of Agnes Wozniak, a maid employed by Pearl Bartlett, Prescott’s elderly neighbor. Though many, including arrogant senior detective Carl Somer, dismiss Pearl as senile, Harriet takes her concerns seriously.

She finds signs of struggle in Agnes’s room, and her thorough inspection sets her apart. Prescott permits her to pursue the case further, and she receives professional support from junior operative Matthew McCabe.

At home, Harriet is guardian to her younger brother Aubrey, whose adolescent struggles add emotional stakes to Harriet’s already complex life.

The investigation leads Harriet to Gunther Clausen, the Bartletts’ imposing handyman, but she quickly rules him out as a suspect. Her interview with Pearl reveals little about Agnes’s personal life, though Pearl’s idle grandnephew, Johnny Bartlett, becomes a person of interest.

Harriet’s visit to the Ali Baba Theater—a male-dominated burlesque venue—exposes her to the darker corners of society, yet she remains steadfast. There she confronts Johnny, who denies any knowledge of Agnes’s disappearance, though his surprise at the news seems genuine.

Further investigation at Lakeshore Domestic Help and Agnes’s previous employers reveals her quiet nature and the suspicion she attracted for supposedly distracting young boys. Harriet then meets Agnes’s sister, Barbara Wozniak, with whom she shares a cautious yet growing connection.

Barbara reveals Agnes had rejected two suitors: Damian Swiatek and the dangerous Bogdan Nowak, a loan shark. This revelation shifts the investigation into more threatening territory.

Tensions escalate when Harriet’s notebook goes missing, and suspicions arise that someone within the agency may be sabotaging her. A visit to Nowak’s pool hall confirms his menacing influence.

Harriet narrowly escapes an attack, shaken but not deterred. Encouraged by Matthew, who gives her shooting lessons and urges her to be cautious, Harriet continues to gather evidence.

Her bicycle is vandalized and she receives subtle threats, but she remains committed.

As she delves deeper into Agnes’s life, Harriet discovers a matchbox linking Agnes to a secret queer club called the Black Rabbit. Barbara agrees to take her there, provided Harriet is honest about who she really is.

Harriet’s confession of her identity strengthens their bond. In Polish Downtown, Harriet meets the Wozniak family.

Agnes’s father, Piotr, is complicit with Nowak, prioritizing money over his daughter’s welfare. One of Agnes’s younger brothers, Marcin, provides a key clue: Agnes had feelings for a man with gray eyes, suggesting a romantic entanglement with Johnny or someone else at the Bartlett household.

When Harriet follows a tip to the Swiatek Sausage Factory, she is nearly mauled by a dog—another sign someone is actively working to stop her. After filing a partial report, she returns home and has a revealing conversation with Aubrey about the personal cost of her ambitions and their shared trauma.

Harriet later visits Nowak’s secret house, only to find a different woman who refuses help, reinforcing how fear and abuse can rob people of agency.

As she heals from her injuries, Harriet reconnects with Pearl Bartlett, who provides emotional support and shares her own story of forbidden love with a woman named Bess. Their conversation strengthens Harriet’s resolve.

With just days left, she approaches Matthew with suspicions about Carl Somer. Though hesitant, he doesn’t stop her.

Disguising herself as a man, Harriet breaks into the Prescott Agency at night, dodging a sleeping operative to retrieve Carl’s personnel file and home address.

Harriet and Barbara plan to confront Carl, but when Barbara’s brothers threaten to turn the visit into a mob scene, Harriet races ahead alone. She finds Agnes alive and safe in Carl’s apartment.

Agnes reveals that she and Carl are in love and staged her disappearance to escape her father and Nowak. Carl, with his knowledge of police procedures, helped design the ruse.

They plan to flee to San Francisco. Though Harriet is stunned by the deception, she sympathizes with Agnes’s desperation.

Before they can finalize their escape, Nowak arrives, having followed Harriet. He kidnaps Agnes again and flees to his pool hall.

Harriet gives chase and confronts him with her derringer. She wounds him, allowing Agnes to flee.

Despite his retaliation, Harriet escapes with her life. She alerts Barbara and her brothers, who begin tracking Agnes.

Harriet rushes to inform Carl, and they meet at the sausage factory, where Nowak and Piotr Wozniak await, armed.

In a final standoff, the siblings confront their father, and just as Nowak prepares to shoot, Piotr turns on him and kills him. The murder marks a brutal end to the ordeal.

Carl is fired for his deception, but Harriet is promoted to full operative and granted her own office. Barbara sends flowers in gratitude, and Harriet’s bond with Matthew deepens.

She has not only uncovered the truth behind Agnes’s disappearance but emerged as a respected detective, confident in her place and purpose.

Characters

Harriet Morrow

Harriet Morrow is the compelling heart of The Case of the Missing Maid, portrayed as a woman of fierce independence and intellect in the restrictive setting of 1898 Chicago. Her identity is rooted in defiance against societal norms—she dresses in masculine attire not only for comfort and practicality but as a symbolic resistance to the confining gender expectations of her time.

Harriet’s arrival at the Prescott Agency marks the beginning of her battle for professional legitimacy in a male-dominated world. Her sharp observational skills and tenacity earn her reluctant respect, especially as she persists where her male colleagues falter, such as in the early investigation into Agnes Wozniak’s disappearance.

Her compassion is equally prominent, especially in her relationship with her younger brother Aubrey, where her protective instincts reveal the emotional cost of her ambition.

Throughout the novel, Harriet undergoes significant growth—not only as a detective but as a woman confronting her own sense of identity, vulnerability, and desire. Her interactions with Barbara Wozniak awaken questions about sexuality and self-discovery, culminating in a powerful personal reckoning at the Black Rabbit drag ball.

Despite setbacks—including sabotage, condescension, and physical danger—Harriet’s sense of justice and integrity remains unshaken. She ultimately earns a place as an official operative at the agency, but more importantly, she claims her voice and authority in a world that seeks to silence her.

Matthew McCabe

Matthew McCabe serves as Harriet’s most consistent ally and quiet champion throughout the narrative. Unlike the other men at the Prescott Agency, he treats Harriet with respect, not condescension, and is genuinely invested in her development and safety.

His calm demeanor, gentlemanly conduct, and practical support—such as offering to take Harriet to the gun range—help ground Harriet amid her many challenges. Matthew also represents a subtle counterpoint to the more volatile men in Harriet’s orbit, offering quiet strength and emotional intelligence.

While their relationship never shifts fully into romantic territory, there are undercurrents of affection and mutual respect that suggest a potential for deeper intimacy. Matthew’s willingness to listen, support, and even bend the rules for Harriet marks him as one of the few male characters who truly sees her for who she is—not just a novelty or threat, but a fellow detective of equal value.

Carl Somer

Carl Somer emerges as Harriet’s primary foil within the Prescott Agency. Arrogant, dismissive, and emblematic of patriarchal entitlement, Carl continually seeks to undermine Harriet’s authority and success.

However, his complexity becomes apparent in the latter part of the novel when it is revealed that he is Agnes Wozniak’s lover and co-conspirator in her staged disappearance. This revelation casts Carl in a more sympathetic light, albeit briefly, as it exposes the personal risk he undertook in attempting to free Agnes from her oppressive circumstances.

Still, his deception ultimately leads to professional downfall, reinforcing the consequences of dishonesty—even when rooted in love. Carl’s arc reveals the limits of redemption when personal rebellion conflicts with institutional integrity.

Barbara Wozniak

Barbara Wozniak is a quiet yet powerful presence in the story, offering Harriet both emotional connection and investigative support. A grounded, intelligent woman, Barbara exudes a steady kind of courage, balancing family loyalty with moral clarity.

Her conversations with Harriet are laced with subtext and emerging intimacy, hinting at a shared yearning for lives unshackled by traditional roles. Barbara’s emotional transparency and integrity create a safe space for Harriet to begin exploring her own feelings, particularly around her gender and sexual identity.

Her invitation to the Black Rabbit serves as a pivotal moment of trust and liberation. Barbara is not just a sister trying to find Agnes; she becomes a mirror and muse for Harriet’s deeper transformation.

Agnes Wozniak

Agnes Wozniak is the enigmatic figure at the center of the mystery. Though absent for much of the narrative, her story is gradually revealed through the eyes of others—sister, suitors, and Harriet.

Agnes is portrayed as independent, principled, and unwilling to submit to the oppressive forces around her, whether those come from an abusive father, a coercive suitor like Bogdan Nowak, or societal expectations of female obedience. Her decision to orchestrate her own disappearance with Carl reflects her desperation and ingenuity, though it also introduces ethical ambiguity.

Agnes ultimately embodies the theme of self-determination, representing the lengths a woman must go to claim ownership over her life and choices in a world designed to trap her.

Bogdan Nowak

Bogdan Nowak is the novel’s most overt villain—menacing, powerful, and unrelenting in his pursuit of control. A violent loan shark with deep ties to Chicago’s underworld, he attempts to claim Agnes as a possession, reinforced by his partnership with her father.

His presence casts a long shadow over the narrative, intensifying the danger Harriet faces. Nowak is not merely a criminal; he is a symbol of the systemic exploitation and misogyny that threatens all women in the novel.

His ultimate demise at the hands of Piotr Wozniak brings a form of rough justice, but his actions have already inflicted lasting trauma, especially on Agnes and her family.

Pearl Bartlett

Pearl Bartlett is an elderly, wealthy woman whose early concern for her missing maid ignites the investigation. While initially dismissed by others, her character proves sharp, compassionate, and unexpectedly radical.

Pearl’s candid sharing of her own love story with another woman adds emotional depth and historical resonance to Harriet’s journey, connecting queer experiences across generations. Pearl is a quiet rebel—living in luxury, but deeply understanding of social marginalization.

Her support for Harriet is subtle but affirming, validating the younger woman’s nonconformity and reminding readers that resistance has long been a part of women’s history.

Aubrey Morrow

Aubrey, Harriet’s younger brother, adds an emotional counterbalance to the high-stakes investigation. As a boy grappling with grief, masculinity, and adolescence, he is both a responsibility and a source of love for Harriet.

Their relationship is fraught but tender, especially when Harriet opens up about her sacrifices and dreams. Aubrey’s evolution from a sullen teen into a supportive brother mirrors Harriet’s own journey into maturity.

He serves as a reminder of what Harriet fights for—safety, freedom, and a better future for those still learning how to shape their own paths.

Themes

Gender Inequality and Female Empowerment

Harriet Morrow’s journey in The Case of the Missing Maid is grounded in a sharp critique of late-19th-century gender norms. Her rejection of traditional feminine fashion, her masculine clothing, and her insistence on physical and intellectual autonomy reflect a deep desire to break free from the suffocating expectations of womanhood in her era.

She is repeatedly underestimated and dismissed by her male peers, particularly by the smug Carl Somer and the coldly indifferent agency culture at Prescott. Yet Harriet never seeks acceptance by conforming; rather, she demands it through competence and defiance.

Her courage in entering the Ali Baba Theater alone, donning bloomers for mobility, and confronting dangerous men in seedy environments, marks her as a woman unwilling to ask permission to participate in male-dominated spaces. Even her final confrontation with Carl and Nowak is defined by her refusal to be sidelined.

Harriet’s tenacity earns her not only professional recognition but the respect of allies like Matthew McCabe. Her evolution from an outsider to a recognized operative reflects broader themes of how women must often outperform, outwit, and outlast their male counterparts just to be acknowledged.

This theme underscores not just her personal transformation but the cultural resistance she must continuously overcome. Harriet’s story becomes a microcosm of the struggle for equality—where merit alone is not enough unless accompanied by self-belief, persistence, and the courage to challenge systemic injustice.

Class Boundaries and Social Stratification

Throughout the novel, the divide between the upper class and working poor is made visible in Harriet’s investigation, particularly through her interactions with both the Bartlett family and the Wozniaks. The Bartlett mansion, a symbol of privilege and social insulation, contrasts starkly with Polish Downtown, a space of immigrant hardship and constrained opportunities.

Agnes, the missing maid, is caught between these worlds—exploited for her beauty and servitude in elite households while simultaneously beholden to a family and community that restricts her choices. The domestic help agency that places women like Agnes, the casual dismissal of her as a potential corrupting influence on boys, and the transactional way her father treats her—all illuminate the commodification of working-class women.

Even Harriet, despite her ambition, remains aware that her social status is tenuous, dependent on proving her usefulness in a male-run organization that is deeply classist. These economic boundaries are not just background details but crucial pressures that shape motivations, limit agency, and determine who gets to disappear without much consequence.

The violence and exploitation endured by women like Agnes are not random—they are embedded in a system that protects wealth and punishes poverty. By exposing these class tensions, the novel suggests that justice is never neutral; it is a luxury often only afforded to those with means and connections.

Identity, Sexuality, and the Cost of Secrecy

The discovery of the Black Rabbit, a hidden queer club, and Harriet’s growing bond with Barbara Wozniak introduce a quieter but profound theme of identity and suppressed sexuality. In 1898, the mere acknowledgment of same-sex attraction or non-normative gender expression was taboo, and the Black Rabbit becomes not only a site of resistance but one of revelation.

Barbara’s openness about her past relationships, and Pearl Bartlett’s confession of love for a woman named Bess, speak to a generation of women whose desires have long been erased or hidden. For Harriet, these moments force a reckoning with her own feelings and fears.

Her decision to dress as a man to infiltrate the Prescott Agency is not simply a tactical move—it resonates with deeper questions about gender presentation and personal freedom. These choices are not without cost.

Harriet’s careful navigation of trust, especially with Barbara, underscores how secrecy can corrode relationships and self-worth. The novel portrays queerness not as a plot twist but as a lived reality that demands courage and carries risk, especially in a society structured to punish deviation.

This theme does not resolve neatly but instead leaves Harriet—and the reader—with the recognition that personal truth can be both liberating and isolating.

Family Obligation and Personal Sacrifice

Harriet’s role as guardian to her younger brother Aubrey infuses the narrative with a tender yet heavy emotional layer. Their relationship, marked by affection, friction, and grief, reveals the toll that responsibility takes on someone already burdened by societal constraints.

Harriet is not simply solving mysteries for career advancement; she is striving to build a future that protects Aubrey from the same systemic barriers she faces. Her late-night conversations, protective instincts, and vulnerability during their arguments reveal how much she sacrifices emotionally.

Aubrey, though young, is perceptive enough to see the weight she carries, and their moments of understanding speak volumes about the complexity of sibling bonds shaped by trauma. This familial obligation is mirrored in the Wozniak household, where Agnes’s father sees her as an asset to be traded rather than a daughter to be protected.

In contrast, Harriet views Aubrey not as a burden but as a reason to keep fighting, even when the odds are against her. The novel uses these familial dynamics to explore how love and duty can empower and confine in equal measure.

The sacrifices Harriet makes are not grand heroic gestures, but daily choices—each shaped by love, guilt, and hope for something better.

Justice, Corruption, and Institutional Complicity

The final chapters of the novel underscore how systems meant to uphold justice can be easily manipulated or complicit in wrongdoing. Carl Somer, a supposed detective committed to truth, becomes a key conspirator in a staged crime.

Prescott Agency, while occasionally supportive, consistently sidelines Harriet until her success can no longer be ignored. The legal system, represented through the absence of meaningful intervention, allows dangerous men like Nowak to operate unchecked.

Even Agnes’s father, supposedly a figure of familial authority, becomes an accessory to his daughter’s abuse. Harriet’s constant need to work outside official channels—breaking into offices, confronting men directly, hiding evidence to protect victims—speaks to a world where true justice must be seized rather than expected.

The climactic confrontation at the sausage factory, where the law is once again absent, forces individuals to take morality into their own hands. Piotr Wozniak’s final act of shooting Nowak is not framed as heroism, but as a last, desperate attempt to reclaim decency.

In this world, justice is not a guaranteed outcome but a fragile, hard-won achievement—dependent on individuals with courage, and often bought with great personal risk. Harriet’s eventual recognition is bittersweet, a reminder that while the truth may emerge, it often comes too late or too costly for those who needed it most.