The Cure for Women Summary and Analysis

Lydia Reeder’s The Cure for Women is a deeply researched and fiercely personal narrative that illuminates the forgotten histories of pioneering women in American medicine. Beginning with the life of the author’s great-grandmother, Ellen Babb—a Missouri midwife whose skills exceeded the limitations society imposed on her—the book uncovers the broader fight for women’s rightful place in healthcare.

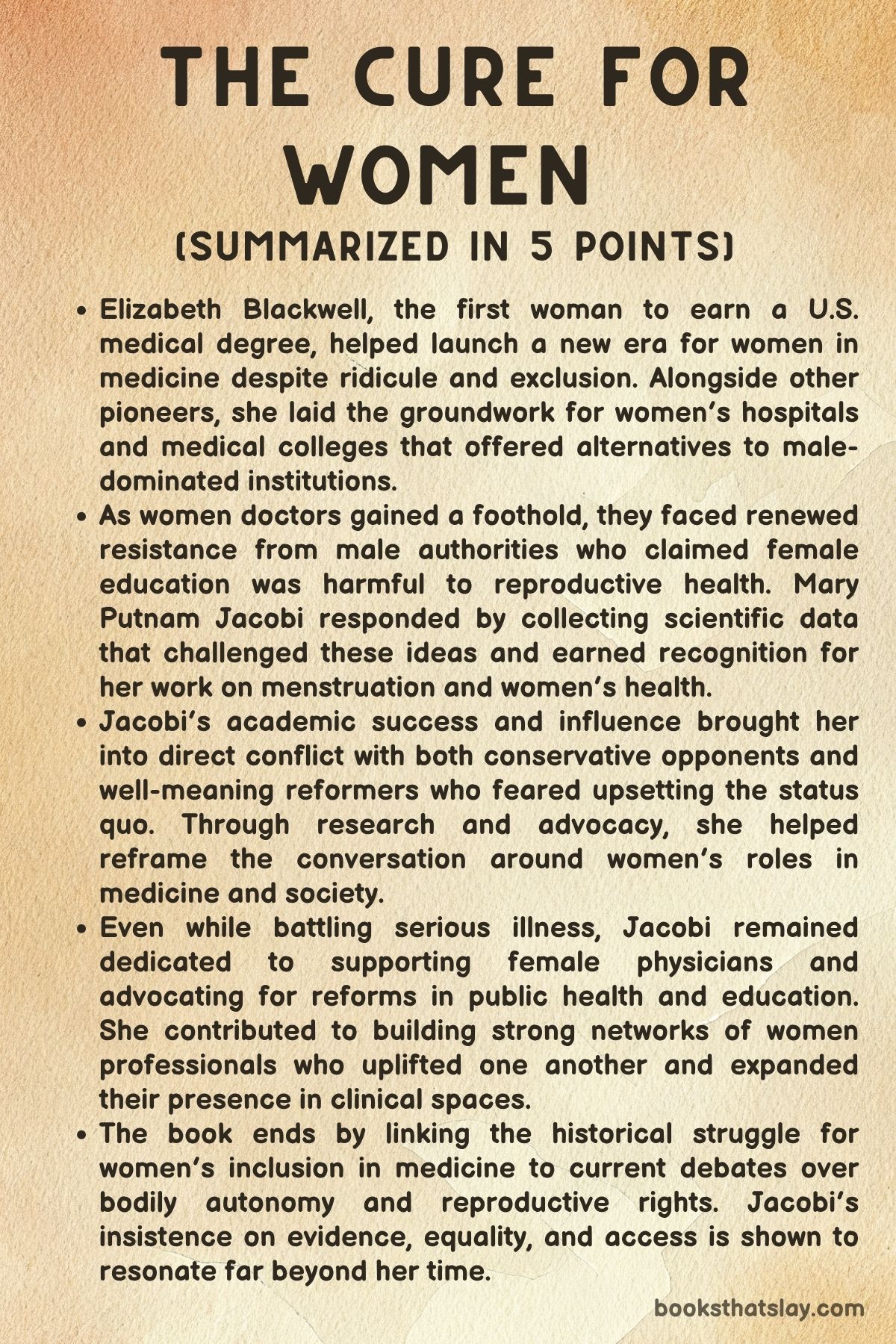

Reeder traces the systemic exclusion women faced from medical education and practice in the 19th and early 20th centuries, highlighting the groundbreaking efforts of Elizabeth Blackwell, Ann Preston, Marie Zakrzewska, and especially Mary Putnam Jacobi. The book positions medicine as a battleground not just for scientific advancement but for gender equity, intellectual legitimacy, and moral reform.

Summary

The story of The Cure for Women begins in 1985 with Lydia Reeder listening to her grandmother and great-aunts recount the life of their mother, Ellen Babb. Ellen was not merely a rural Missouri midwife; she was a healer of rare competence, performing life-saving interventions with ingenuity and resolve.

Her career offers a powerful example of the medical skill women possessed but were long denied institutional recognition for. Ellen’s story acts as the gateway into a larger investigation, prompting Reeder to uncover how American women historically fought for inclusion in the male-dominated field of medicine.

This investigation takes readers back to the mid-19th century, when cultural and scientific assumptions about gender, biology, and intellect were weaponized against women seeking medical education. Influential male figures like Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

, Edward Clarke, and J. Marion Sims argued that female anatomy was incompatible with rigorous thought.

They claimed that menstruation and reproductive fragility rendered women unfit for higher education or professional labor, framing female intellectual aspiration as a medical risk that threatened not only individual health but also the future of the race.

Despite such entrenched resistance, the first wave of women doctors began carving pathways into the profession. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree in 1849.

Shut out of internships and faculty roles, she built her own practice and partnered with other determined women like Ann Preston and Marie Zakrzewska. Together, they created institutions that would both serve vulnerable populations and train future women doctors.

These included the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children and the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania—radical acts that challenged not just medicine’s gender exclusivity but its ethical foundations.

As the professionalization of medicine intensified, so did the backlash against women. J.

Marion Sims gained prominence by performing experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women without anesthesia, using their suffering to advance gynecological science. His notoriety underscored the violence embedded in male-controlled medicine and reinforced women’s belief in the need for female-led care.

Zakrzewska, originally a midwife trained in Berlin, brought scientific rigor to American obstetrics, but had to fight for every credential. Her efforts, and those of her colleagues, were animated by both necessity and justice.

Among this vanguard, Mary Putnam Jacobi emerged as the most intellectually formidable. Her journey from Civil War nurse to Sorbonne-trained physician reveals a commitment to rigorous science and feminist reform.

Inspired by her brother’s wartime illness and her experiences with Blackwell’s network, Jacobi rejected the substandard instruction at women’s colleges and fought to receive training on par with men. After excelling in Parisian laboratories and earning top academic honors, she returned to New York equipped to challenge the foundational myths that kept women in social and professional subjugation.

Jacobi’s work extended far beyond clinical practice. She launched a scientific offensive against the era’s dominant beliefs about menstruation and female fragility.

Her award-winning essay, The Question of Rest for Women During Menstruation, dismantled the idea that menstruation was disabling. Through experimental observation and data from hundreds of women, she demonstrated that women were physiologically capable of work during menstruation and that societal health relied more on nutrition and consistent labor than rest.

Her success in winning the Harvard Boylston Medical Prize—the first woman to do so—marked a turning point in the intellectual validation of women’s bodily experience.

However, acceptance did not come easily. S.Weir Mitchell, architect of the notorious “rest cure,” dismissed Jacobi’s research and continued to advocate for treatments that isolated and infantilized women. Jacobi engaged in public battles with Mitchell, exposing his practices as unscientific and harmful.

Her rebuttals, rooted in data and clinical evidence, made her a rare voice in an environment that often sidelined women’s contributions. Even so, many of her insights were later appropriated or obscured by male researchers.

Her activism deepened over time. When Johns Hopkins University hesitated to accept women into its medical program—even with a funding offer—Jacobi was part of the movement that forced its hand.

She helped mobilize public pressure through op-eds, political lobbying, and direct appeals to major donors. Mary Elizabeth Garrett ultimately secured women’s access to the university with a conditional endowment, ensuring that female students would be held to the same academic standards as men.

In 1893, the school admitted women, marking a new era in medical education.

Yet Jacobi did not stop at medical reform. Personal losses, including the death of her young son, catalyzed a shift toward political advocacy.

She launched a strategic suffrage campaign in New York that united working-class and elite women, using “parlor meetings” to foster discourse and gather petition signatures. Her speech at the 1894 New York Constitutional Convention argued that enfranchisement was a natural extension of women’s evolution.

Though the measure failed, she channeled momentum into the creation of the League for Political Education.

Jacobi’s mentorship influenced younger doctors like Emily Dunning, who became New York’s first female ambulance surgeon. She also helped revive the career of writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, using a therapeutic approach that emphasized intellectual engagement over seclusion.

Even during her terminal illness, Jacobi conducted a self-study of her brain tumor’s progression, leaving behind one last scientific contribution before her death in 1906.

The book closes by reflecting on how the stories of Ellen Babb, Elizabeth Blackwell, Marie Zakrzewska, and especially Mary Putnam Jacobi form an unbroken thread of resistance. They challenged institutional sexism, revised medical knowledge, and changed how the female body was understood and treated.

The Cure for Women reveals how medicine was not just a site of healing, but a field of ideological struggle—one that women fought to transform from within. Their legacy persists in every classroom, clinic, and lab that welcomes women as equals.

Key People

Ellen Babb

Ellen Babb stands as the emotional and ideological cornerstone of The Cure for Women, embodying the blend of compassion, ingenuity, and quiet resistance that defined many early female healers. Operating in rural Missouri in the early 1900s, Ellen was more than a midwife—she was a vital community lifeline.

Her practical skills, such as extracting a swallowed safety pin or engineering a makeshift incubator to save a premature baby, underscore her medical intuition and adaptability. These acts, though not sanctioned by formal training, were no less heroic or sophisticated than those performed in sterile, male-dominated hospitals.

Ellen’s thwarted dream of becoming a physician reflects the systemic barriers women faced, and her legacy of service and sacrifice becomes the catalyst for the author’s journey into feminist medical history. Her narrative reveals how personal ambition, when met with societal denial, can transform into communal leadership and maternal strength, offering an implicit critique of institutional exclusion.

Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell emerges as a pioneering figure whose historic achievement—becoming the first woman in the United States to earn a medical degree—ushers in a new era for women in medicine. Her triumph in 1849 is both personal and political; after being denied positions in hospitals due to her gender, she turns adversity into opportunity by establishing her own practice and eventually co-founding the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children.

Blackwell’s resilience is matched by her strategic vision: she recognizes that systemic change requires both institutional infrastructure and the cultivation of like-minded allies. Her collaboration with figures like Ann Preston and Marie Zakrzewska reveals her ability to unite diverse talents for a common cause.

Although she could sometimes be conservative in her views on feminism, her work provided a foundation upon which later reformers—more radical in ideology—could build. Blackwell is thus portrayed as both a symbol of breakthrough and a bridge to deeper reform.

Ann Preston

Ann Preston is depicted as the moral conscience and activist engine within the growing coalition of female physicians. A Quaker and an abolitionist, Preston channels her spiritual and political convictions into the fight for women’s inclusion in medicine.

She becomes a key player in creating spaces where women could not only practice but also train others—building a self-sustaining model of medical education that did not rely on the approval of the patriarchal establishment. Preston’s importance lies not just in her institutional achievements but also in her ability to mobilize ethical arguments in favor of coeducation and professional equality.

Her activism positions her as both a practitioner and a philosophical leader, emphasizing that healing must be inseparable from justice. In The Cure for Women, she represents the interweaving of medicine, morality, and social responsibility.

Marie Zakrzewska

Marie Zakrzewska’s story is one of transnational ambition and relentless perseverance. Trained as a midwife in Berlin, she brings her extensive knowledge to America, only to face cultural and institutional resistance.

Her collaboration with Elizabeth Blackwell proves pivotal, as it allows her to channel her skills into the creation of hospitals and educational programs tailored for women. Zakrzewska’s clinical excellence and her rigorous standards help to elevate the credibility of female-led institutions.

She is portrayed as a pragmatic reformer, less focused on public rhetoric and more on building systems of care. Her emphasis on obstetrics and hospital management gives a practical backbone to the feminist ideals espoused by others in the movement.

Through Zakrzewska, the book illustrates how immigrant narratives and international training enriched the fight for women’s medical rights in the U. S., underscoring the global dimensions of local revolutions.

Mary Putnam Jacobi

Mary Putnam Jacobi is portrayed as the intellectual and revolutionary heart of the feminist medical movement. Her biography, rich with defiance, loss, and scientific triumph, shows a woman who refused to accept the limitations imposed by gender.

From nursing her brother during the Civil War to earning a medical degree in Paris under harrowing siege conditions, Jacobi’s life exemplifies resilience and brilliance. She critiques and ultimately dismantles prevailing theories of female fragility, especially through her landmark essay debunking the myth that menstruation required rest.

Her empirical research, involving physiological data from hundreds of women, redefined female biology in scientific terms and laid the foundation for modern gynecology. Jacobi’s activism extends beyond medicine into suffrage and education reform, making her a formidable force in both the scientific and political arenas.

Her final act—documenting her own brain tumor—turns her death into yet another contribution to medical knowledge. In The Cure for Women, Jacobi symbolizes the fusion of reason, resistance, and reform, standing as perhaps the most intellectually expansive figure in the narrative.

S. Weir Mitchell

S. Weir Mitchell, though a central antagonist, is an essential figure in understanding the entrenched misogyny of 19th-century medicine.

His infamous “rest cure” encapsulates the patronizing and often harmful medical practices that dismissed women’s ailments as hysteria or nervous disorders. Mitchell’s theories reflect broader cultural anxieties about women’s independence, intellectual capacity, and reproductive control.

Through him, the text critiques not only individual prejudice but institutionalized sexism masquerading as science. His professional rivalry with Jacobi highlights the tension between empirical evidence and gendered assumptions.

Mitchell’s legacy, though celebrated in his time, is sharply reevaluated in the text, rendering him a cautionary symbol of how power and pseudoscience can reinforce each other.

President Gilman and Mary Elizabeth Garrett

President Gilman represents institutional resistance to coeducation, cloaking patriarchal bias in administrative caution. His reluctance to accept female donors’ conditions at Johns Hopkins Medical School reveals how male leaders attempted to maintain control over evolving norms.

By contrast, Mary Elizabeth Garrett embodies strategic philanthropy as a form of feminist activism. Her substantial donation, tied to strict conditions for academic rigor and equal access, effectively forces the institution’s hand.

Garrett’s actions demonstrate the power of financial leverage in dismantling gender barriers and emphasize the importance of resourceful, behind-the-scenes advocacy. Together, their story in The Cure for Women captures a pivotal moment where public policy, private capital, and gender politics converge.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Though a secondary figure, Charlotte Perkins Gilman serves as a poignant symbol of the psychological toll of patriarchal medicine. Once subjected to Mitchell’s rest cure, her career and well-being suffered under his misguided treatment.

Her eventual rehabilitation under Jacobi’s cognitive and social approach reflects a healing that is both medical and ideological. Gilman’s presence in the book not only reinforces Jacobi’s influence but also bridges literature and medicine, showing how feminist reform could resonate across disciplines.

Her recovery under Jacobi’s care becomes a narrative of reclaimed agency, intellectual rejuvenation, and feminist solidarity.

Themes

Gendered Barriers in Medicine

The history presented in The Cure for Women powerfully illustrates how institutionalized sexism shaped—and was deliberately used to restrict—women’s entry into the medical profession. Male physicians and educators weaponized pseudo-science and cultural anxieties to argue that women’s bodies were too fragile for intellectual or physical labor, effectively gatekeeping access to medical education and professional roles.

Figures like Edward Clarke, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. , and J. Marion Sims used scientific rhetoric not to advance health, but to preserve gender hierarchies. They claimed women would become infertile if educated, thereby framing exclusion as a protective measure, even as it masked deeply patriarchal control over knowledge and reproduction.

These arguments were not fringe ideas but were upheld by leading institutions and widely circulated publications, influencing generations of policy and medical practice. Meanwhile, male physicians conducted unethical experiments on enslaved and impoverished women, building careers off procedures that would become mainstream, while simultaneously denying those same women recognition, relief, or restitution.

Against this backdrop, women like Ellen Babb, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Marie Zakrzewska stood not only as healers but as living contradictions to the prevailing ideology. Their existence, competence, and persistence exposed the fallacy of supposed female inferiority.

The theme underlines that women’s historical exclusion from medicine wasn’t the result of biological incapacity, but of cultural engineering and systemic oppression.

Community-Based Healing Versus Institutional Medicine

Ellen Babb’s story embodies a deeply rooted tradition of community-centered healing, one grounded in experience, necessity, and trust rather than formal accreditation. Her work—extracting safety pins from children’s throats, reviving premature infants, and offering midwifery care—was not only life-saving but often more responsive to the needs of her rural Missouri community than the services of credentialed doctors.

Yet despite her proven skill, she was never allowed to formally study medicine due to societal expectations and educational gatekeeping. Her story presents a sharp contrast to the elitist, male-dominated institutions that excluded women on ideological grounds, even as they lacked the practical abilities women like Ellen had mastered.

This contrast illustrates a central theme in the book: that genuine medical expertise often existed outside institutional boundaries, especially among women. Furthermore, the value of compassionate, socially embedded care is elevated over detached, hierarchical clinical models.

The divide between practical healing and credentialed practice reveals how power, more than capability, determined who was allowed to treat and who was treated as subordinate. The book critiques how professionalization in medicine became synonymous with male dominance and institutional prestige, sidelining generations of women whose work saved lives long before medical degrees were accessible to them.

Scientific Rigor as a Tool for Feminist Advancement

Mary Putnam Jacobi’s career challenges the 19th-century medical orthodoxy that claimed female biology was inherently defective. Rather than rejecting science outright, Jacobi used it as a powerful tool to dismantle the myths that marginalized women.

Her empirical research on menstruation—tracking real physiological data such as pulse, temperature, and strength—disproved widely accepted ideas that menstruation necessitated rest or isolation. By showing that many women remained active and even physiologically stronger during their cycles, she disrupted entrenched notions of fragility.

This theme underscores how women used the very language and methodology of science to demand equality, not by asking for exceptions, but by proving their fitness for inclusion. Jacobi’s use of data, statistical analysis, and lab experimentation not only earned her accolades but also reshaped gynecological science.

However, the resistance she faced—both in the erasure of her findings and in continued exclusion from institutional power—reveals how even evidence-based argumentation was insufficient to completely overcome gender bias. Nonetheless, Jacobi’s insistence on rigorous science as a feminist act created a new framework for activism, one that linked bodily autonomy with epistemological authority.

Her example reframes feminism as not only a political but a scientific endeavor, demanding both rights and recognition through proof, reason, and method.

Education as Resistance and Reform

The quest for women’s admission to institutions like Johns Hopkins Medical School reveals how education functioned not merely as personal advancement, but as collective resistance. The women who pledged funds for Johns Hopkins did so not to carve a space within an existing patriarchal system, but to transform the system itself by mandating equal admission standards and educational rigor.

This move directly countered the narrative that women needed separate or lesser training. Figures like Mary Elizabeth Garrett and Mary Putnam Jacobi recognized that true reform required systemic change, not isolated access.

Their activism exposed how elite male-led institutions often feigned open-mindedness while privately resisting inclusion, hoping for male donors to override women’s financial leverage. The strategic use of funding, public pressure, and logical argumentation—especially Jacobi’s speeches and essays—forced institutions to confront their own contradictions.

Education, in this context, becomes a battlefield, where women negotiate legitimacy, challenge intellectual apartheid, and reshape public discourse. Even after gaining entry, the continued marginalization of women within academic and clinical spaces revealed that equality on paper did not guarantee parity in experience.

Yet these early victories set precedents that rippled outward, transforming not only who could become a doctor, but how medicine itself would be taught, practiced, and defined.

Intersection of Medicine, Race, and Class

The book draws necessary attention to how medical advancements were often built on the exploitation of vulnerable populations, particularly enslaved Black women and impoverished immigrants. J.

Marion Sims, revered as a surgical pioneer, gained fame through experiments that inflicted suffering on enslaved women without anesthesia or consent. These women were treated not as patients but as tools for male ambition.

Their pain was both invisible and foundational to the professional success of men who would later shape the field. At the same time, immigrant women like Marie Zakrzewska had to navigate ethnic prejudice, limited economic opportunities, and gender bias, making their successes even more significant.

This intersectional dynamic reveals how medicine was not only gendered but racialized and classed, with those at the margins often subjected to brutality or exclusion. It also reflects how women of different backgrounds—whether freedmen’s daughters, working-class midwives, or wealthy activists—contributed uniquely to the fight for a more humane and inclusive medical system.

The narrative forces readers to reconsider medical progress not as a neutral or universally beneficial process, but as one deeply embedded in and shaped by societal inequalities. Through this lens, the struggle for ethical, inclusive care becomes inseparable from broader movements for racial and economic justice.

Bodily Autonomy and Political Agency

Jacobi’s later turn toward suffrage activism signals the culmination of a belief that physical and political autonomy are intrinsically connected. Her medical career had already challenged essentialist ideas about women’s biology, and she extended that same logic to political rights, arguing that if women’s bodies were not inherently inferior, then their exclusion from civic life was equally baseless.

Her “Common Sense” treatise and address to the New York Constitutional Convention framed suffrage not as a sentimental cause but as a rational extension of evolutionary and democratic principles. This approach positioned her as a bridge between scientific inquiry and political reform.

The idea that a woman’s right to vote, to study, to heal, and to speak were all facets of the same struggle grounded her multifaceted activism. Her rejection of the “rest cure” paralleled her resistance to enforced passivity in the political realm.

By connecting medical advocacy to civic participation, the text emphasizes that the fight for bodily self-determination could not be won without systemic political change. Her mentorship of figures like Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her insistence on coeducation signal an enduring belief that reform must occur simultaneously across multiple dimensions of society, and that science, education, and democracy are all co-dependent realms in the pursuit of equality.