The French Winemaker’s Daughter Summary, Characters and Themes

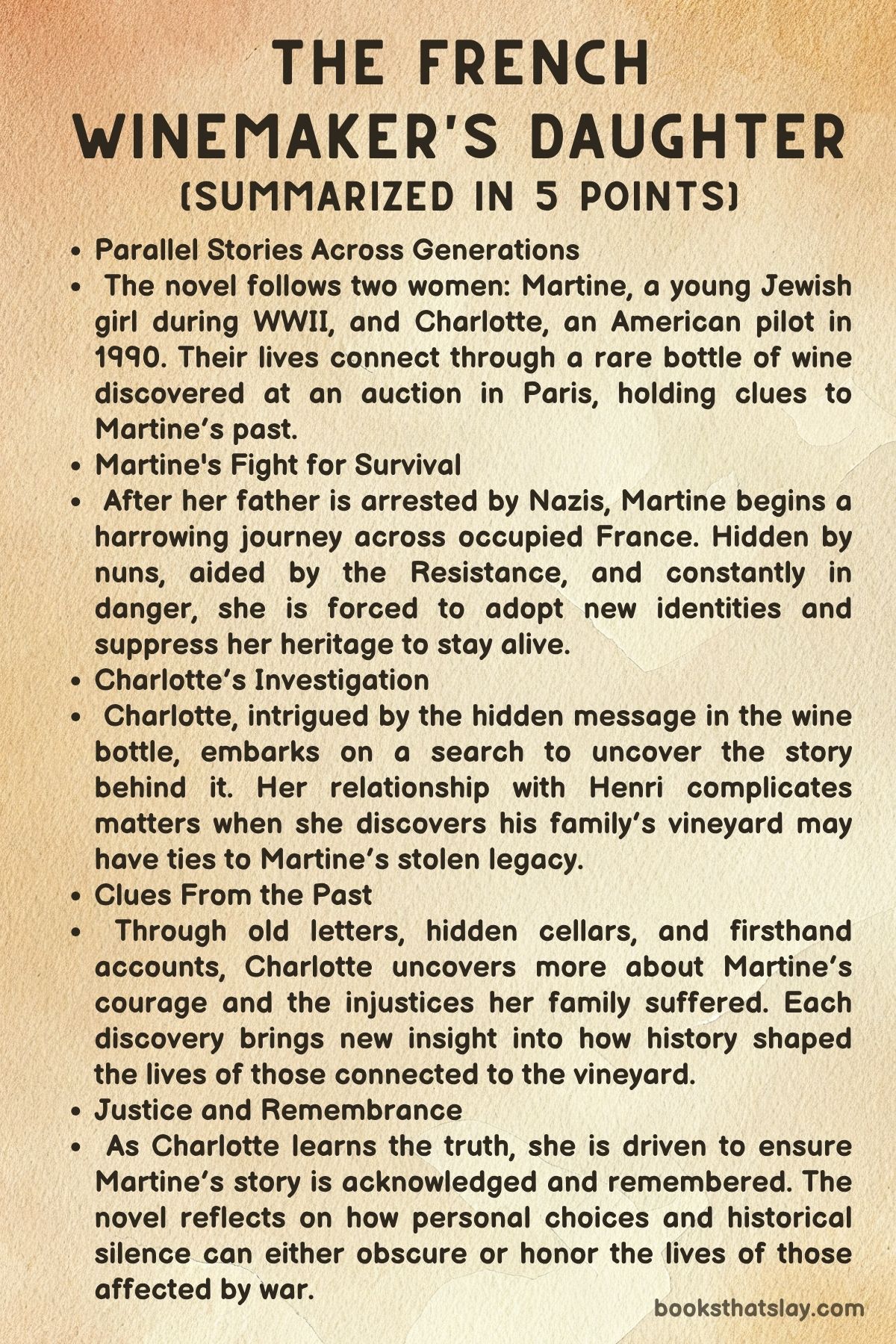

The French Winemaker’s Daughter by Loretta Ellsworth is a dual-timeline historical fiction novel that explores the lingering echoes of war, memory, and inheritance through the intertwined lives of two women separated by nearly half a century. Set in 1940s Nazi-occupied France and 1990s Paris, it follows Martine Viner, a young Jewish girl forced into hiding after her father’s arrest, and Charlotte Montgomery, a determined American pilot uncovering the mystery of a hidden message inside an old wine bottle.

Through the lens of legacy, survival, and rediscovered identity, the novel offers a moving meditation on how the past shapes the present in both quiet and transformative ways.

Summary

The story begins in 1942 in Burgundy, France, with eight-year-old Martine Viner living a quiet, insulated life among vineyards with her father Zachariah. She is bright in unconventional ways, deeply connected to viticulture, but misunderstood in school due to her learning difficulties.

Her father, however, treasures her and encourages her intuitive brilliance. Their peaceful world is shattered when German soldiers arrive to arrest Zachariah for being Jewish.

He hides Martine inside an armoire, masking the moment as a game to protect her from trauma. Before being taken, he ties a note inside her dress, promising that a bottle of wine will provide for her future.

After the arrest, Martine narrowly escapes and seeks help from the Moreau family.

Though Madame Moreau is cold and anti-Semitic, Monsieur Moreau helps Martine. He reads the note sewn into her clothing and arranges for her to flee under a new identity: Élise Moreau.

Hidden under straw in a wagon, she is smuggled toward Paris. Along the way, she clings to the address of her aunt, repeating it like a mantra.

At the train station, a woman offers her kindness, and Martine continues her journey alone, filled with uncertainty but driven by her father’s hope.

When she arrives in Paris, she finds her aunt’s apartment, only to learn that Tante Anna has also been taken. The woman who now lives there cruelly rebuffs Martine and threatens her.

Homeless and traumatized, Martine collapses near Hôtel Drouot, holding her stuffed rabbit. She is discovered and cared for by Sister Ada, a nun at an abbey outside Paris.

Though wary at first, Martine begins to trust Ada, who advises her to pretend she is Catholic. Martine learns to recite prayers and begins to recover emotionally.

As she adapts to life at the abbey, she discovers Ada is not a real nun but a Jewish woman in hiding, secretly working with the Resistance.

Meanwhile, the narrative shifts to 1990 in Paris. Charlotte Montgomery is an accomplished American pilot grappling with romantic disillusionment and career challenges.

At an auction with her French boyfriend Henri, Charlotte accidentally wins a crate of wine confiscated during WWII. While examining the bottles, she uncovers a hidden note written by a man named Zachariah Viner, indicating the wine was meant for his daughter.

Curious and moved by the letter’s implication, Charlotte begins to investigate the wine’s origins. With help from her academic friend Paul, she learns the bottle could be worth a fortune—but more importantly, it holds historical weight.

Charlotte reflects on her grandfather, a veteran and vineyard owner, whose emotional struggles post-war resonate with the trauma embedded in the wine’s history. As her relationship with Henri deteriorates due to his indifference and opportunism, Charlotte becomes more committed to finding the rightful heir of the wine.

Her search takes her to Burgundy, where she visits towns and vineyards, looking for traces of the Viner family. She meets Madame Reza, a retired teacher, who remembers the Viners and confirms their Jewish identity.

Reza’s view of Martine is dismissive, calling her mentally challenged and overly attached to a rabbit, but her memories guide Charlotte to the vineyard now called Clos Lapointe.

Back at the abbey in 1943, Martine begins to thrive under Sister Ada’s guidance. Ada teaches her to read, revealing Martine’s capacity to learn with the right support.

Martine becomes aware of Ada’s Resistance work and wrestles with fear, secrecy, and the burden of survival. Ada considers placing Martine in an orphanage with forged papers for safety, but Martine refuses, clinging to their bond.

Their relationship evolves into one of deep love, with Ada becoming a surrogate mother and protector.

In a pivotal chapter, Martine visits a village with Ada. She is overcome with memories of her father when passing vineyards.

In the town square, she witnesses the bodies of hanged Resistance fighters—a horrifying sight that imprints the harsh reality of occupation on her young mind. Ada tries to shield her, but the image lingers.

At the orphanage, Martine is offered a chance to stay among other children, but she insists on remaining with Ada at the abbey, reaffirming their connection.

Back in 1990, Charlotte’s journey continues. Her pursuit leads her to Georges, the current vintner at Clos Lapointe.

He recognizes the name Viner and provides Charlotte with a photograph of Martine and another bottle from the same vintage. Charlotte’s sense of purpose is strengthened, while her relationship with Henri falls apart completely, as he is more concerned with the wine’s monetary value than its historical importance.

Charlotte finds new companionship with Julien, a charming Parisian with legal expertise. After a romantic evening together, Charlotte is served legal papers from Henri, who is suing her for possession of the wine.

Julien offers his support and is shocked when he sees the photograph of Martine, recognizing her resemblance to his own mother, Élisabeth. He proposes that they might be the same person, which Charlotte initially rejects.

Later, her research confirms the truth: Martine survived the war, was adopted by Ada and her fiancé André, and became Élisabeth Katz.

In a climactic courtroom scene, Julien outsmarts Henri by substituting the wine bottle, neutralizing his legal claim. Charlotte relinquishes the original bottle—not in defeat, but to return it to its rightful owner, Martine/Élisabeth.

This act of integrity affirms Charlotte’s moral compass and completes her emotional arc. The wine, once a commodity, becomes a vessel of memory, love, and restored identity.

The novel concludes with Charlotte and Julien visiting the vineyard where Martine once lived and hid. They reflect on the passage of time, inherited trauma, and love’s ability to persist.

Charlotte, having fulfilled her promise to uncover Martine’s fate, also opens her heart to the future, standing at the intersection of history and healing.

Characters

Martine Viner

Martine Viner is the emotional heart of The French Winemaker’s Daughter, a child whose journey from innocence to resilience is shaped by war, loss, and transformation. As a young Jewish girl living in Burgundy during the Nazi occupation, Martine begins the novel with a deep love for the vineyard life and an extraordinary connection to her father, who cherishes her despite her struggles with conventional education.

Her understanding of the land and grapes offers a unique intelligence, though society often overlooks it. Her life is shattered when her father is arrested, forcing her into survival mode at an impossibly young age.

Through Martine’s eyes, we experience the trauma of war: the terror of hiding in an armoire, the pain of seeing her father’s arrest, and the cruel rejection at her aunt’s Paris apartment. Her emotional depth deepens as she bonds with Sister Ada, whose gentle guidance helps Martine relearn trust, identity, and literacy.

Her growth is subtle but powerful—from a frightened child into a girl who embraces dual religious practices, navigates dangerous masquerades, and ultimately reclaims her voice through reading. Martine becomes a symbol of perseverance, identity, and the haunting legacy of forgotten lives.

Charlotte Montgomery

Charlotte Montgomery represents the modern soul searching for purpose beyond surface-level ambition. As an American pilot in 1990 Paris, she is initially portrayed as a confident professional woman entangled in a superficial relationship with Henri, a man who values possessions more than people.

Charlotte’s character arc blossoms when she encounters the mysterious wine bottle containing a note from Zachariah Viner to his daughter. What begins as a curiosity soon evolves into a moral quest rooted in empathy and personal reckoning.

Charlotte is guided not by guilt, but by a fierce sense of justice and human connection. Her grandfather’s PTSD and vineyard history deepen her emotional connection to the past, lending a generational thread to her motivations.

Her journey becomes as much about understanding Martine’s legacy as about discovering her own values. Through interactions with locals, rejection of Henri’s materialism, and her evolving relationship with Julien, Charlotte transforms into a woman driven by love, memory, and moral clarity.

Her final act of giving the wine to Élisabeth not only restores a family legacy but affirms Charlotte’s character as one of compassion and integrity.

Sister Ada

Sister Ada is a complex figure of compassion, deception, and quiet rebellion. Though initially perceived as a Catholic nun, she is later revealed to be a secular Jew hiding in plain sight.

Her dual identity makes her one of the most intriguing characters in The French Winemaker’s Daughter, embodying both resistance and maternal care. Ada becomes Martine’s lifeline—offering her food, shelter, religious guidance, and above all, love.

She teaches Martine to blend into her surroundings, prepares her with forged documents, and gently nurtures her into literacy. Their bond is sacred, transcending conventional roles of guardian and child.

Ada’s involvement in the French Resistance through her fiancé André reveals her bravery, while her nurturing spirit underscores her commitment to preserving Jewish heritage in a time of erasure. She is both protector and rebel, grounding Martine in faith and love while fighting injustice with quiet tenacity.

Zachariah Viner

Zachariah Viner, though absent for most of the narrative, looms large through the love he pours into a bottle of wine and the note hidden within it. A devoted father and skilled winemaker, Zachariah represents the personal tragedies behind countless historical statistics.

His decision to hide Martine and prepare a legacy for her through the wine reflects his foresight, courage, and deep paternal devotion. The note he writes becomes the emotional anchor of the novel, transcending time and acting as the catalyst for Charlotte’s journey.

His character is symbolic of all the displaced, erased, and forgotten lives during the Holocaust—men and women whose legacies lived on through the smallest acts of love and resistance.

Julien

Julien begins as a romantic interest but soon emerges as a moral ally and emotional counterpart to Charlotte. His layered identity—as a lawyer, a romantic, and the son of Élisabeth Katz (formerly Martine)—adds emotional weight to his character.

Julien is respectful, principled, and unafraid to confront difficult truths, even when they involve his own family’s buried past. His relationship with Charlotte is built on mutual respect and emotional transparency, contrasting sharply with Henri’s superficiality.

Julien’s role in neutralizing Henri’s legal threat and supporting Charlotte’s mission makes him an embodiment of moral intelligence and emotional sensitivity. His journey, too, becomes one of rediscovery and reconnection—with his mother’s hidden identity and with a legacy that had been lost.

Élisabeth Katz (formerly Martine)

Élisabeth Katz is the adult incarnation of Martine, and her revelation as Julien’s mother creates one of the novel’s most powerful moments of catharsis. Her transformation from a scared, orphaned child to a woman who survived, adapted, and formed a family is nothing short of remarkable.

Though she remains unaware of her true past for much of her life, the wine and the note reconnect her with her father’s love and her own origin story. Through Charlotte’s efforts, she gains closure, identity, and belonging.

Élisabeth stands as a testament to survival, and her character bridges the past and present in a profoundly moving way, affirming that even the most painful histories can be reclaimed through love and truth.

Henri

Henri functions as a foil to both Julien and Charlotte. He is charming and cosmopolitan but ultimately shallow and self-serving.

His interest in the wine and willingness to sue Charlotte over it showcase his transactional nature. Henri values ownership and prestige over human connection, making him emblematic of a world that prioritizes material gain over moral purpose.

His character is necessary to highlight the stark contrast between possessiveness and legacy, between love and exploitation. His eventual failure to reclaim the wine represents not only a legal defeat but a moral one.

Themes

Identity and Inheritance

Charlotte’s accidental discovery of the wine bottle bearing a hidden message from Zachariah Viner sets off a profound meditation on the complexity of identity, especially when shaped by loss, war, and displacement. For Martine, identity is repeatedly stripped and reconstructed—from a beloved daughter in Burgundy to a Jewish fugitive named Élise Moreau, and eventually to Martine Blanchet, a fictitious Catholic orphan under protection.

Each name and persona is a survival strategy, imposed externally yet shaping her internally. These forced identities create a fragmented sense of self, with her only constant being the wine bottle and memories of her father.

As she adapts to these names, Martine’s true self—her Jewish heritage, her bond with her father, and her trauma—remains locked away for safety. Decades later, Charlotte’s efforts to uncover Martine’s past emphasize how identity can be recovered, even reconstituted, through acts of remembrance and recognition.

The inheritance, symbolized by the wine bottle, is not monetary but existential—it restores Martine’s stolen past, validates her experience, and reconnects a severed lineage. For Élisabeth, formerly Martine, receiving the wine completes a personal restoration.

Her son Julien’s recognition of her past, through a mere photograph, bridges generations and heals a wound never spoken aloud. Thus, the theme of identity and inheritance is not confined to genetics or legal documentation but is presented as an emotional legacy—passed down, lost, and ultimately reclaimed through acts of courage and empathy.

Moral Responsibility and Historical Memory

Charlotte’s decision to investigate the origins of the wine bottle despite having no obligation to do so underscores the theme of moral responsibility across time. She is not Jewish, not French, and not connected by blood to the Viner family, yet she feels compelled to honor the plea of a desperate father who entrusted a wine bottle with his daughter’s survival.

This inner call reveals how individuals can shoulder responsibility for history, not out of guilt, but out of a sense of decency and human solidarity. Charlotte’s journey becomes an act of witness—she not only uncovers Martine’s story but ensures it is remembered and respected.

This stands in stark contrast to characters like Henri, who view the bottle solely as a financial asset, disregarding its historical and emotional weight. The novel suggests that forgetting is a form of complicity; the past, particularly one as violent and unjust as the Holocaust, demands active engagement and moral reckoning.

Martine’s own efforts to preserve her father’s memory, through prayer and literacy, echo this same ethic from a child’s perspective. In resisting the erasure of her identity and past, she affirms that memory is an act of defiance against brutality.

The interplay between Charlotte and Martine’s narratives shows how historical trauma requires multigenerational acknowledgment—not just for restitution, but for healing. In honoring a long-silenced voice, Charlotte transforms personal curiosity into moral action, offering a model for how contemporary individuals can engage with the past in a meaningful, ethical way.

Love as Protection and Devotion

In The French Winemaker’s Daughter, love is not portrayed as grand romantic gestures, but as acts of protection, nurturing, and sacrifice. Zachariah Viner’s love for Martine is illustrated in his final desperate act—hiding her in the armoire, giving her a bottle of wine as inheritance, and embedding a message of survival into her clothing.

These actions are saturated with tenderness and foresight, driven by the hope that love, even in the face of annihilation, can preserve a future. Sister Ada’s role continues this pattern.

Though not a biological relative, she becomes Martine’s protector, teacher, and surrogate mother. Her willingness to risk her own life to shelter Martine, and her decision to teach Martine both Jewish and Catholic prayers, reflects a deep understanding that love sometimes means transcending personal identity for another’s safety.

Ada’s guidance nurtures Martine back to life, reminding her that she is not alone, even in hiding. Similarly, in the contemporary narrative, Charlotte’s relationship with Julien matures when love ceases to be about passion or possession and becomes about mutual trust, forgiveness, and emotional honesty.

Julien’s legal defense of Charlotte, his intuitive recognition of Martine’s photograph, and his respect for her mission, all point to a model of love based not on desire, but on support and truth-telling. Through these arcs, the novel explores how love—whether paternal, platonic, or romantic—is measured not in declarations but in steadfastness during crisis.

It’s a protective force that, when genuine, shields not only the body but the soul, especially in a world capable of tremendous cruelty.

Trauma, Silence, and Recovery

Martine’s story is steeped in trauma, from witnessing her father’s arrest to seeing corpses hanging in a public square. These are not events that can be processed easily, especially by a child.

Instead of dramatizing her pain, the novel portrays it through her silence, reluctance to engage with others, and fierce attachment to Sister Ada. Martine’s refusal to play with the other children or to leave Ada’s side speaks volumes about the psychological scars left by war and loss.

Silence becomes both a survival tool and a symptom of unprocessed grief. In the 1990s narrative, Charlotte’s discovery of Martine’s fate breaks this silence, bringing the truth to light and initiating a process of intergenerational healing.

The trauma doesn’t disappear, but its acknowledgment offers a kind of release. For Élisabeth, now living with a buried identity, receiving her father’s bottle and letter reopens a wound but also validates her lost past.

Recovery in the novel is portrayed as slow, fragile, and incomplete, but also possible. Charlotte’s own emotional wounds—rooted in her fear of commitment, her grandfather’s PTSD, and her dissatisfaction with Henri—are addressed through her growing involvement in Martine’s story.

Understanding the trauma of others allows her to recognize her own emotional needs and boundaries. The novel thus draws a link between historical trauma and personal healing, suggesting that recovery is an act of acknowledgment.

It is not forgetting the past but honoring it, speaking it aloud, and integrating it into one’s identity without letting it define or destroy the self.

Courage and Resistance in Ordinary Acts

The narrative highlights how extraordinary bravery can exist in small, unremarkable choices. Sister Ada is not part of the armed Resistance in the conventional sense; she does not carry weapons or lead rebellions.

Yet her daily decision to protect Martine, teach her, and disguise her as a Catholic child is an act of quiet resistance that endangers her life. Ada’s love for André and her faith in Martine’s future become her motivators, and through her, the story honors those who resisted not through violence, but through kindness, deception, and moral integrity.

Similarly, Martine’s courage is not loud or showy. It’s present in her ability to remember addresses, adopt new names, stay silent when required, and refuse to be broken by the horrors she sees.

Even in her refusal to leave Ada when offered the chance to stay at the orphanage, she asserts agency and loyalty. Charlotte, too, exercises a different form of resistance—against apathy, cynicism, and greed.

When others dismiss the bottle as a collectible or a legal liability, she insists on its meaning. She resists the temptation to forget, to simplify, or to profit.

Each of these women—across time and circumstance—resists the forces that try to erase memory, identity, and connection. The novel honors the unsung bravery of individuals who, even in fear, choose action over passivity, and compassion over self-interest.

It shows how true resistance lies not just in defiance, but in preserving humanity when it would be easier to abandon it.