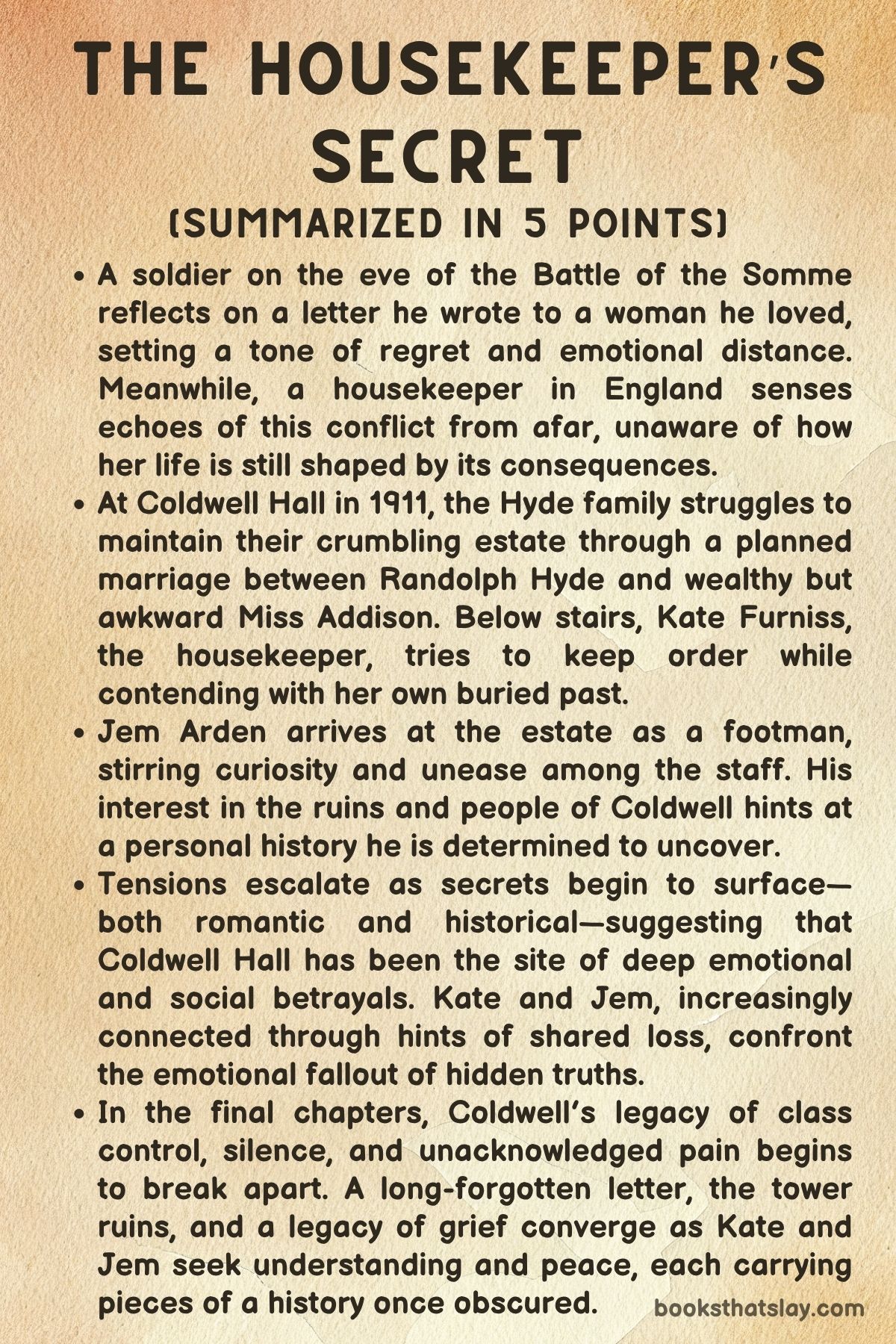

The Housekeeper’s Secret Summary, Characters and Themes

The Housekeepers Secret by Iona Grey is a sweeping historical drama set in Edwardian England, anchored by a chilling mystery, complex characters, and the haunting legacy of a decaying aristocratic estate. Through the shifting perspectives of those who serve and those who inherit, it paints a vivid portrait of a rigid class system on the verge of collapse, and the secrets it traps within.

At its core is a forbidden romance between a housekeeper with a hidden past and a footman with a vengeful mission. Their love grows in the shadow of a crime buried in time—one that unearths personal grief, social injustice, and a longing for redemption amid the echoes of empire and the trauma of war.

Summary

The story opens in 1911 at Coldwell Hall, a once-grand estate now fading under the weight of its past. The narrative begins with Eliza, a young maid, and Kate Furniss, the efficient but secretive housekeeper, both struggling to maintain order ahead of a crucial house party that might secure the estate’s financial future through the engagement of Randolph Hyde to Miss Addison.

As the pressure mounts downstairs, upstairs politics and expectations sharpen, with Kate balancing the demanding needs of nobility with dwindling resources and a skeleton crew of staff.

The arrival of a new footman, Jem Arden, quietly unsettles the routine. Jem is not merely a servant; he’s searching for the truth about his brother Jack, who disappeared at Coldwell after a house party in 1902.

Jem believes Randolph Hyde was involved. Hired under false pretenses, Jem observes and investigates, his presence stirring unease in Kate, who seems to recognize him from a distant memory.

Coldwell Hall, once a seat of imperial pride, is now a haunting monument to loss, arrogance, and secrets.

Jem’s private mission becomes complicated by his growing attraction to Kate. Their shared pasts, heavy with loss and deception, create a tentative connection.

Kate, known to the staff as Mrs. Furniss, is hiding her true identity: she is Kate Ross, estranged wife of the disgraced Alec Ross.

Her sense of safety crumbles as she realizes that the people and power structures she escaped may be closing in again.

As the story progresses, Jem and Kate are drawn into increasingly dangerous territory. Jem uncovers that Jack had been humiliated and potentially murdered during a cruel hunting game staged by Randolph and his aristocratic companions.

A servant, Mullins, who was present that night, eventually confesses under duress that Jack was dressed as a tiger in a mock hunt, hunted down for sport, and left to die. The shame and horror of that night were silenced with bribes and threats.

Jem is consumed by grief and rage, but also by the need to protect Kate, who is now in danger due to her assumed identity.

Kate’s own peril escalates when Henderson, the valet who helped cover up the past, recognizes her and begins to blackmail and menace her. In a chilling scene, Henderson attempts to assault her in the gamekeeper’s cottage.

Kate is saved by Davy Wells, a vulnerable local boy she once helped, who becomes a silent guardian. Though physically unscathed, Kate is emotionally fractured, increasingly aware that her safety, identity, and budding love with Jem are all in jeopardy.

Meanwhile, a growing bond between Jem and young hallboy Joseph adds emotional weight. Jem sees in Joseph a version of his younger self, lost and vulnerable.

Joseph, in turn, finds in Jem a protective figure. The importance of chosen family becomes a recurring theme as the house’s secrets threaten to implode.

The narrative intensifies with a series of dramatic turns. Jem is falsely accused and becomes a fugitive, hiding in the village church as Boxing Day arrives.

Simultaneously, Coldwell’s annual servants’ ball is revived by a surprise string quartet. Amid the festivities, tension bubbles just beneath the surface.

Kate, coerced into wearing a dress from her privileged past, is visibly uncomfortable, especially as Henderson manipulates her with threats of exposure.

Jem is ambushed by Henderson and his accomplice Robson in the church. He is left injured in a tunnel but is rescued by Davy, who finally breaks his silence and recounts the true horror of Jack’s death: Henderson had stripped Jack and abandoned him in the tunnel to die of exposure.

Davy’s testimony confirms the cruelty Jem suspected but never fully knew.

Back at Coldwell, Eliza, now more observant and mature, notices a bloodstain on Robson’s shirt during the ball. Jem returns to the hall in a wounded state, scaring the staff and demanding to see Kate.

He discovers Henderson’s body in her sitting room, stabbed with her embroidery scissors. Kate is gone, aided by Miss Dunn, Miss Addison’s maid, who had earlier and inadvertently exposed Kate’s identity.

Wracked with guilt, Miss Dunn redeems herself by helping Kate flee Coldwell with the musicians. The women part with quiet understanding and unspoken truths.

In the aftermath, Jem recovers in a local hospital. Joseph confesses that he was the one who killed Henderson, driven by guilt and fear.

The staff quietly protect him, unwilling to see another life destroyed. Jem, respecting Joseph’s act of protection and repentance, chooses silence over justice.

The story edges toward closure with this act of mercy.

The epilogue, set in 1918, brings peace at last. The war is over.

Kate and Jem have survived and are married, living in the countryside with their newborn son, Jack—named after Jem’s brother. Their new life is modest but free, built not on deception or fear but on truth and love.

Though scarred by years of suffering, they find peace in each other and in the quiet beauty of a world no longer ruled by Coldwell’s ghosts.

The Housekeepers Secret closes with a sense of renewal. Though the past cannot be undone, its hold is broken.

The novel honors the resilience of the marginalized, the healing power of love, and the human capacity for reinvention in the face of violence, trauma, and betrayal.

Characters

Kate Furniss

Kate Furniss, the housekeeper of Coldwell Hall, emerges as one of the most complex and layered characters in The Housekeepers Secret. Introduced as the capable and composed Mrs.

Furniss, she is in truth a woman living under an assumed identity, using her role as a protective shell against a past filled with betrayal, trauma, and disgrace. Her transformation from Kate Ross to Mrs.

Furniss is not merely a change of name but a symbolic act of survival, a way of severing ties with a marriage marked by violence and shame. As a housekeeper, she is efficient and commanding, earning the respect of her staff.

Yet beneath this façade lies a woman tormented by memory, drawn inexorably toward the secrets Coldwell Hall harbors.

Her emotional journey is deeply tied to Jem Arden, with whom she shares a forbidden love that evolves from mutual suspicion into a powerful, redemptive bond. Kate’s struggle is both external—navigating the rigid class hierarchies and expectations of Edwardian service—and internal, wrestling with guilt, desire, and the haunting legacy of Coldwell’s cruelty.

Her attempted assault at the hands of Henderson, and her stoic reaction to it, underscore her quiet strength and fierce dignity. Kate’s eventual flight from Coldwell and her life as Eliza Simmons reflect a painful but necessary metamorphosis.

Her reunion with Jem and her new identity as a wife and mother symbolize not just personal healing, but the possibility of rebirth after years of suppression and loss.

Jem Arden

Jem Arden is the emotional fulcrum of the novel’s mystery and revenge narrative. Arriving at Coldwell Hall under the guise of a second footman, Jem’s true motive is to uncover the fate of his brother Jack, who disappeared after attending an aristocratic gathering at the estate in 1902.

Jem’s initial portrayal is that of a brooding and emotionally guarded man, but as the story unfolds, he reveals a moral intensity and depth of feeling that elevate him far beyond the role he pretends to inhabit. His anger, directed chiefly at Randolph Hyde and the corrupt world of privilege, is tempered by a growing affection for Kate, whose own secrets mirror his own.

Jem’s arc moves from vengeance to vulnerability. His love for Kate softens his single-minded focus, revealing a capacity for tenderness and compassion even amid the weight of grief.

His interactions with younger characters like Joseph and Davy Wells further illustrate his instinct to protect the vulnerable—a foil to the predation and silence that Coldwell once encouraged. Jem’s bravery is tested not just in the battlefield trenches, where he reflects on mortality and guilt, but in his choice to seek truth rather than revenge.

By the novel’s end, Jem has been physically broken, emotionally exhausted, but spiritually renewed. His decision to shelter Joseph after Henderson’s murder instead of exposing him is a quiet act of grace.

In marrying Kate and naming their son Jack, Jem reclaims the love, family, and peace denied to him for so long.

Randolph Hyde

Randolph Hyde represents the decaying moral and financial core of the Coldwell aristocracy. He is arrogant, emotionally stunted, and entitled—a man born into privilege but utterly lacking in empathy or accountability.

His role in the tragic events surrounding Jack Arden is indicative of the cruelty that often masqueraded as amusement among the upper classes. The “tiger hunt” incident, in which Jack was mocked, hunted, and left for dead while dressed in Indian costume, is a horrific display of racialized and class-based violence.

Randolph’s transactional approach to marriage, treating Miss Addison as a means to financial salvation, reflects the commodification of women and relationships typical of his class.

Despite being a central antagonist, Randolph is not a straightforward villain. He is a product of a system that valued status over humanity, legacy over justice.

His disdain for Coldwell’s crumbling estate is mirrored in his contempt for the people who maintain it, including the staff who silently suffer under his rule. His actions catalyze much of the conflict in the novel, and while his end is not one of violent comeuppance, the truth about his past and the loss of power at Coldwell mark his ultimate downfall.

He is the embodiment of privilege corrupted—his legacy hollowed out by the very traditions he sought to preserve.

Miss Dunn

Miss Dunn, initially introduced as the maid to Miss Addison, evolves into one of the most intriguing and redemptive figures in the novel. Observant and intelligent, she quickly discerns the undercurrents of tension and unspoken history at Coldwell.

While she remains a secondary character for much of the novel, her quiet presence belies a significant role in the unfolding drama. Her eventual confession—that she inadvertently betrayed Kate’s identity to Henderson—brings her into the moral center of the story.

Drugged and manipulated, her guilt leads her to risk everything to help Kate escape.

Miss Dunn’s transformation from passive observer to active participant in Kate’s liberation is a powerful statement about agency and sisterhood. Her final act—providing Kate with the means to disappear and start anew—demonstrates a deeply personal form of atonement.

She may not have intended harm, but she takes full responsibility for her part in exposing a vulnerable woman. In doing so, she reclaims her voice and power in a society that typically grants neither to women in her position.

Miss Dunn’s arc is about recognition—of her own strength, of her complicity, and ultimately of her capacity for redemption.

Joseph Jones

Joseph is introduced as a seemingly peripheral figure—a hallboy largely overlooked in the hierarchy of service. Yet his character becomes increasingly significant as the story progresses.

Mentored by Jem and shown kindness by Kate, Joseph slowly emerges from the shadows of neglect and self-doubt. His relationship with Jem is especially touching, providing a glimpse into his hunger for validation and purpose.

Joseph’s internal conflict crescendos when he kills Henderson in a moment of desperate courage. While his action is technically criminal, the novel treats it with moral nuance—Henderson’s predation and violence make Joseph’s act an almost inevitable rebellion against abuse.

Joseph’s confession and the staff’s decision to shield him speak to the novel’s deeper themes of communal justice and the power of chosen family. He is a symbol of the countless voiceless young people exploited and forgotten by systems of class and labor.

In being spared punishment and embraced by those who understand the full weight of his trauma, Joseph is offered something rare in this world: a second chance. His presence in the epilogue, through the letter he writes to Kate, is a quiet reminder of the long shadows the past can cast—and the fragile hope that healing is still possible.

Davy Wells

Davy Wells, the silent and emotionally fragile boy from the local village, may seem peripheral at first, but he plays a pivotal role in both the emotional and narrative resolution of the novel. Muted by trauma and alienated by his differences, Davy is treated with both pity and suspicion by those around him.

However, his connection to Kate and Jem is deepened through acts of bravery that belie his apparent vulnerability. His intervention during Henderson’s attempted assault on Kate not only saves her but also symbolizes the hidden strength of the overlooked and underestimated.

Davy’s ultimate act of courage—rescuing Jem and revealing the truth about Jack’s death—marks the climax of his emotional arc. Breaking his silence is both a literal and symbolic liberation, one that validates the horror he witnessed and contributes to justice finally being served.

Davy is the novel’s emblem of truth long buried, the witness whose trauma is finally honored. His quiet presence and eventual voice underscore a recurring theme in The Housekeepers Secret: that healing, while painful, is possible, and that sometimes the smallest voices carry the most powerful truths.

Eliza

Eliza begins the novel as a young maid, wide-eyed and eager to prove herself, but her arc is one of disillusionment and maturation. The opulence and ritual of Coldwell, initially awe-inspiring, soon reveal their dark underside.

Eliza is observant, emotionally intelligent, and increasingly skeptical of the narratives around her. By the time of the servants’ ball, she has shed the romantic notions that once defined her, choosing independence over naiveté.

Her rejection of Robson and her astute observation of the blood on his shirt demonstrate her growing autonomy and discernment.

Eliza’s presence at key narrative moments allows her to serve as a bridge between the domestic and the subversive, the personal and the political. She is witness to Jem’s injuries, Joseph’s confession, and the collapse of the old order at Coldwell.

Her maturity is further evidenced in the epilogue, where she updates Jem about Kate and Joseph. Eliza represents a younger generation that has learned from the past’s mistakes and is perhaps more equipped to navigate the uncertainties of the future.

She is not a revolutionary, but she is quietly transformative—a testament to the enduring power of observation, reflection, and quiet resistance.

Themes

Power and Class Hierarchies

In The Housekeeper’s Secret, the unyielding structures of power and class are embedded in every corner of Coldwell Hall, dictating not only how people live and work, but how they are seen and remembered. The aristocracy, represented by Sir Henry Hyde and his son Randolph, hold onto a dwindling legacy of colonial wealth, yet demand the same obedience and reverence from those beneath them.

Coldwell Hall, once a symbol of imperial glory, now stands as a rotting monument to the arrogance and decay of that legacy. The servants exist in a separate world beneath the surface—overworked, underpaid, and invisible, yet their labor is what sustains the illusion of nobility.

The novel carefully explores how power operates both overtly—through orders, threats, and employment contracts—and subtly, through gaze, silence, and physical proximity. Kate Furniss, the housekeeper, expertly manipulates her position to maintain control, but she is still beholden to the whims of the family she serves.

Jem Arden, as a footman with an ulterior motive, sees this class dynamic from a dual perspective: both as participant and investigator. Even the visiting Miss Dunn, seemingly on the periphery, observes and registers class signals, revealing how deeply encoded the system is in posture, tone, and attire.

Power is always in motion, but rarely in flux—until the narrative’s climax begins to disrupt the expected outcomes. The downfall of Henderson, the exposure of aristocratic brutality, and the eventual flight and reinvention of Kate mark the moment when those beneath the hierarchy not only see the structure but begin to rewrite it.

Identity and Reinvention

The shifting identities in The Housekeeper’s Secret are not simply a matter of disguise—they are lifelines for survival in a world where women and working-class individuals have limited agency. Kate Furniss, who is in truth Kate Ross, has constructed an entirely new persona after the disgrace of her past marriage.

Her transformation is not cosmetic but deeply existential. Every moment of her life at Coldwell depends on maintaining a fiction, one that grants her respect, authority, and autonomy.

Yet this identity is constantly under threat—from documents, from men like Henderson, and from her own past catching up. Jem Arden also inhabits a dual role, posing as a servant while quietly seeking justice for his brother’s death.

His assumed identity is both a mask and a weapon. Even Joseph, the hallboy, embodies this theme as he transitions from a background figure to someone capable of life-altering violence and moral awakening.

Reinvention in the novel is often fraught with risk but also offers liberation. Miss Dunn’s confession near the end reveals her own entanglement in performance and regret, further reinforcing that identity in this world is as much a social negotiation as it is a private reality.

By the end of the story, when Kate adopts the name Eliza Simmons and works in a war hospital, her new life is hard-won and deeply symbolic—a reclaiming of selfhood not just from her past, but from the systems that tried to erase her. Reinvention is shown as painful and incomplete, but it is also the clearest path to freedom.

Gendered Violence and Silence

The story offers a harrowing and realistic examination of how violence against women is both normalized and concealed within patriarchal systems. Henderson, whose public face is polished and professional, operates as a predator behind closed doors, relying on power imbalances, fear, and silence to shield his abuse.

Kate’s near-assault in the gamekeeper’s cottage is a moment charged with terror, not just for the physical threat but for what it represents—how quickly a woman’s safety, dignity, and identity can be shattered. Her response, a ritualistic washing and withdrawal from others, mirrors the trauma of many women who experience such violations.

Silence becomes a coping mechanism, but it also isolates. Throughout the novel, women communicate in glances, half-finished sentences, and hushed tones—Miss Dunn’s failure to confess in time, Eliza’s wary observations, and Kate’s internal monologues all suggest how little room there is for direct speech in a world shaped by male authority.

Even when justice arrives in the form of Henderson’s death, it is ambiguous, incomplete, and dependent on another male’s confession—Joseph’s. The novel does not offer a simplistic narrative of retribution; instead, it emphasizes how enduring and corrosive such violence can be, and how the structures that enable it are deeply embedded in both the domestic and social world.

The path to healing, as represented in the epilogue, requires not only escape but the building of a new life free from the gaze and judgment of the old.

The Haunting Past

In The Housekeeper’s Secret, history is never dormant. Coldwell Hall is physically and symbolically filled with ghosts—both literal and metaphorical.

The story of Jack, hunted through the woods in a grotesque parody of colonial sport, anchors the novel’s central mystery, but the past lingers in other ways as well. The decaying rooms, the preserved silver from India, the disused visitors’ book—all are relics of a former age that continues to cast shadows.

Jem’s investigation resurrects these shadows, but the process exacts a psychological cost. Kate, too, is pursued by the past, not only in terms of personal guilt but also in the systems and expectations that try to keep her contained.

The narrative continually reveals how little has truly changed despite the surface of time passing. The reappearance of figures like Mullins, the confessions of Davy, and even the seasonal rituals like the servants’ ball suggest a cyclical relationship to history: it is not linear or concluded but repetitive and unresolved.

The story critiques this by finally breaking the cycle. Henderson’s death, Joseph’s decision to speak the truth, and the departure of Kate from Coldwell all represent ruptures in the pattern.

But even in the final scenes, the scars of the past remain visible—Jack’s name lives on in Jem and Kate’s son, not as closure but as remembrance. The novel insists that the past cannot be erased, only acknowledged, mourned, and carried forward with intention.

Love as Resistance

In a world governed by hierarchy, reputation, and violence, the romantic connection between Kate and Jem becomes more than emotional—it becomes an act of resistance. Their love is dangerous, not simply because of the impropriety of their roles, but because it asserts human dignity in the face of systems designed to crush it.

Each stolen moment between them, whether a shared glance or an embrace in a disused bedroom, is a rebellion against the loneliness and surveillance that defines life at Coldwell. Their desire is not escapist but rooted in reality; they are not dreamers but survivors who find in each other something necessary and redemptive.

The risks they take to connect—to confide in one another, to comfort, to hope—are enormous. Kate, carrying the weight of her past, fears vulnerability.

Jem, consumed by grief and a quest for truth, fears distraction. Yet they persist, and in doing so, they create a space of emotional safety that defies the coldness of their surroundings.

Their bond is tested repeatedly—by missed meetings, trauma, and social danger—but it endures. The epilogue affirms this endurance not with grandeur but with quiet domesticity: a home, a child, a sense of peace.

Love, in the novel’s view, does not erase hardship or magically resolve pain, but it can anchor people through upheaval and become the foundation for a different kind of life—one based not on secrets and fear, but on honesty and care. In the harsh landscape of the narrative, love is not fragile; it is defiant.