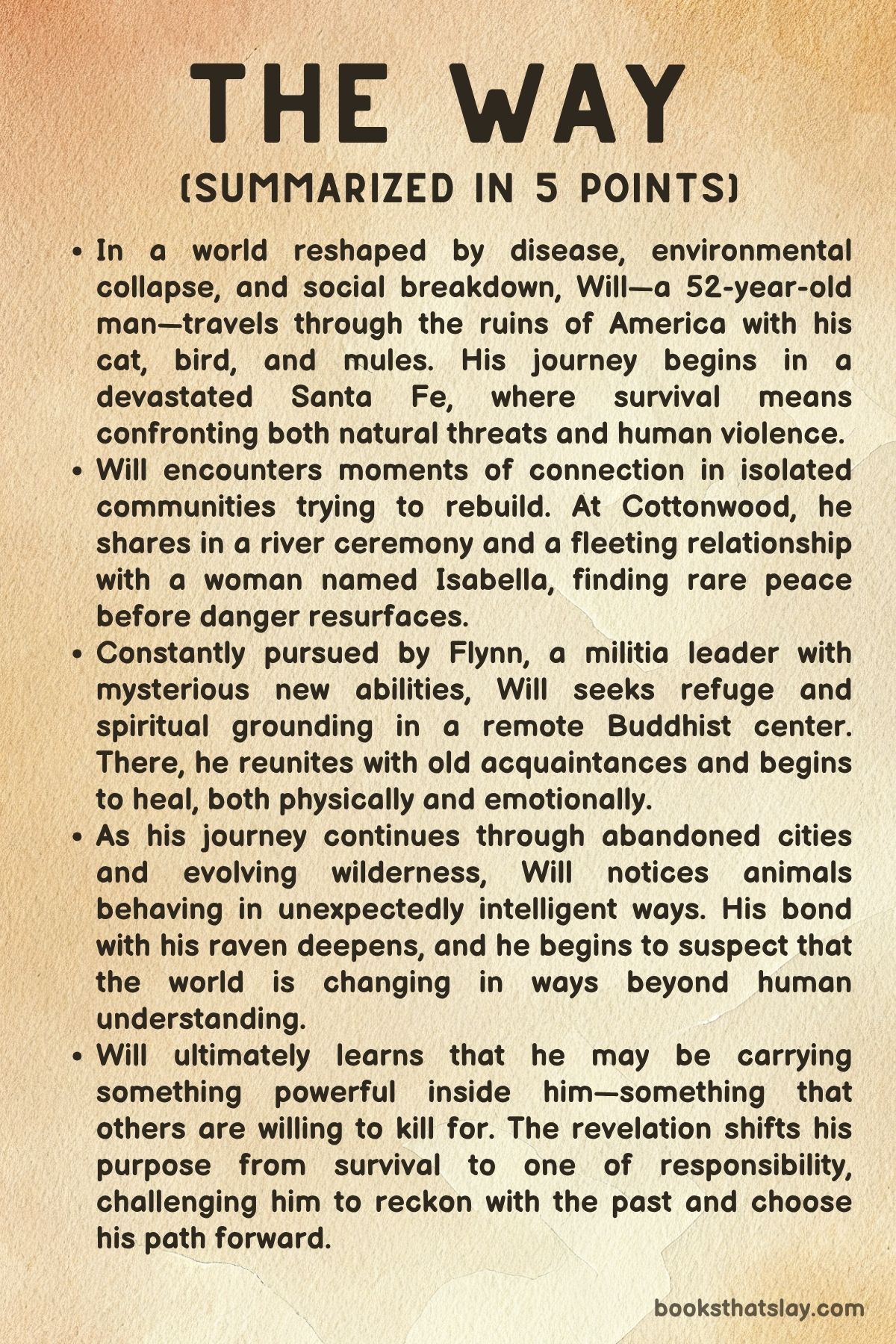

The Way by Cary Groner Summary, Characters and Themes

The Way by Cary Groner is a philosophical and emotionally resonant journey across a ravaged American landscape. Set in a future where environmental disaster and social collapse have unraveled civilization, the novel follows Will, an aging wanderer haunted by loss and seeking redemption.

Accompanied by two unlikely allies—a perceptive raven named Peau and a loyal cat named Cass—Will travels westward to deliver a mysterious medical ampoule to California. What unfolds is a meditative odyssey through ruin, memory, connection, and the persistent flicker of hope. Groner’s narrative explores humanity’s failures and resilience with depth, humor, and a reverence for life in all its forms.

Summary

The Way begins in a broken and desolate America, where Will, the narrator, makes a slow journey westward. His only companions are Cassie, a large cat with sharp instincts, and Peau, a raven with the uncanny ability to understand and mimic language.

They move via a mule-drawn vehicle, a stripped-down remnant of pre-apocalypse technology. Their purpose is quietly urgent—Will carries within his body a tiny ampoule embedded in his molar, believed to be a cure for a deadly disease known as Disease X.

Their path is fraught with hardship, danger, and philosophical introspection.

As they traverse the ruins of the Southwest, through cities like Santa Fe and Albuquerque, Will reflects deeply on the collapse of civilization. He notes the return of wild animals to the abandoned spaces once dominated by humans and considers the fluid boundary between sanity and survival in this new world.

The presence of animals like Peau, who can communicate on some level, becomes both a comfort and a challenge to his understanding of consciousness and connection.

One night, their camp is invaded by armed men from a brutal militia group called ARM, led by the enigmatic Buck Flynn. When all seems lost, a tiger drawn by the scent of a nearby horse carcass unexpectedly kills the attackers, saving Will and his companions.

This moment, terrifying and awe-inspiring, underscores the surreal and primal quality of the world they now inhabit.

Haunted by his memories, especially of his lost love Eva, Will writes her a letter and burns it in ritualistic fashion, as he often does. These letters are acts of mourning and communion, reaching into the unknown.

As he moves forward, he arrives in Cottonwood, a riverside town guarded by a community of young survivors who have constructed a fragile but functional society. Here, he meets Isabella, a woman who candidly shares that she is likely in the early stages of Disease X.

Their connection is brief but genuine. They share resources, dance, drink, and speak openly about fear, love, and the precariousness of their lives.

Yet, Will cannot stay. His mission calls him further west.

After parting ways with Isabella, he makes his way toward the hermitage of a spiritual mentor named David Marsh. On the road, Will once again writes to Eva and questions the nature of death, the soul, and whether his words ever reach her.

One night, he is encircled by unknown animals whose collective wail seems to mourn the dying world. He takes it as a profound, cosmic moment of recognition and sorrow.

Eventually, with the help of Peau, he locates David’s retreat. There, he reconnects with Pelageya, a girl he once knew who has survived into young adulthood alongside David.

Their reunion is emotional and grounding. David offers not only physical sanctuary but also deep spiritual reflection.

Their conversations, informed by Buddhist thought, explore the contradictions of doing good in a broken world. Will shares his letters to Eva, and David encourages him to believe in their unseen reception.

They perform a sacred ritual together, and for the first time in years, Will feels spiritually anchored.

Resuming his journey, Will reaches Princely, a town that somehow retains electricity and structure. Here, he meets Serena, a madame who operates a brothel, and Sophie, a sharp-tongued 14-year-old girl at risk of being drawn into exploitation.

Will contemplates rescuing her, sensing in her a spark of life he can help preserve. Just as they prepare to leave together, Will detects signs that Buck Flynn is nearby and flees with Sophie, driven again by both threat and responsibility.

Their bond deepens on the road. Sophie, shaped by a traumatic upbringing in an orphanage during the collapse, shares her story.

Together with Cass and Peau, they navigate the dangerous terrain. They discover a hidden, solar-powered mansion that once belonged to screenwriters, complete with books, films, and a luxurious pool.

It becomes a temporary paradise. However, Sophie falls ill, possibly from a mutated avian flu.

Desperate and uncertain, Will performs a Buddhist ritual and accepts Peau’s offering of a strange medicinal plant. Sophie recovers, affirming a deepening sense of spiritual purpose for Will and solidifying their surrogate father-daughter bond.

They leave the sanctuary to continue their mission. In the Mojave Desert, their train-like transport breaks down.

In Bakersfield, they are attacked by feral children, and Sophie defends Will with a gun, severing part of an assailant’s finger. Their harrowing escape leads them into a herd of bison, where they find brief peace.

Sophie uses the raven language, strengthening her bond with Peau and asserting her evolving identity.

Next comes a terrifying tunnel and a final confrontation with Buck Flynn. Will and Sophie sabotage the tracks, triggering a fiery derailment.

Flynn survives but is blinded and pursued by ravens. Cornered and disfigured, he takes his own life.

Will and Sophie are later rescued by a coastal research community. There, Will undergoes surgery to retrieve the ampoule from his jaw, and it is administered to Eva, who has survived in a comatose state.

Eva awakens, and the emotional reunion with Will is overwhelming. She reveals that she had a daughter, Lily, lost during the societal collapse.

Clues suggest that Sophie may be that lost child, though certainty remains elusive. In a reversal of traditional adoption, Sophie symbolically adopts Will and Eva, choosing them as her family.

The gesture emphasizes mutual care, chosen bonds, and the reconstruction of identity through love.

As the novel concludes, the characters begin to heal. Will finds serenity through meditation and connection, Eva begins reclaiming her voice and presence, and Sophie imagines a future within a budding new community.

Watching the sunset together, they share a moment of quiet, earned peace. The story closes with a sense of fragile hope and reaffirmed humanity, a tribute to endurance, compassion, and the stubborn desire to believe in something better.

Characters

Will

Will, the protagonist of The Way, is a deeply introspective, emotionally burdened man navigating the decaying remnants of civilization. Haunted by memory and philosophical inquiry, he embodies the paradox of survival in a world stripped of meaning.

A former scientist with Buddhist leanings, he wrestles constantly with the futility of human ambition, the trauma of ecological collapse, and the aching void left by lost love. Will is a reluctant savior, driven by a moral imperative rather than heroism.

His implanted ampoule, possibly a cure for Disease X, becomes symbolic of his quiet but tenacious commitment to hope. His bonds with animals, especially the raven Peau and the cat Cassie, blur traditional lines of interspecies connection and highlight his adaptive, almost spiritual empathy.

Will’s encounters—whether with a dying world, spiritual hermits, or traumatized survivors—draw out a profound humanism marked by compassion, reflection, and a weary resolve to keep moving forward.

Sophie

Sophie emerges as one of the most compelling and transformative figures in The Way. Introduced as a hardened fourteen-year-old on the brink of exploitation, she quickly subverts expectations with her intelligence, wit, and emotional complexity.

Despite her youth, Sophie has endured the collapse of societal structures, orphanhood, and the constant threat of violence, all of which have forged a guarded, self-reliant persona. Yet, under Will’s reluctant but growing mentorship, she displays not only a keen philosophical mind—debating gender roles, literature, and ethics—but also an emotional depth that allows her to bond deeply with others.

Her relationship with Will evolves into a surrogate father-daughter dynamic, suffused with tenderness and mutual care. Sophie is not simply a symbol of the next generation; she is a co-architect of meaning in a broken world, challenging Will’s cynicism and offering moments of laughter, insight, and resilience.

Her recovery from illness and potential identity as Eva’s daughter add layers of mystery and poignancy, reframing her as both a product of the past and a bridge to an unknowable future.

Eva

Eva, though physically absent for much of The Way, exerts a powerful gravitational pull on Will’s emotional and philosophical trajectory. A brilliant scientist and former lover, she represents both the intellectual idealism and emotional intimacy of the pre-apocalyptic world.

Through Will’s letters—burned as ritualistic offerings—Eva becomes a vessel for grief, longing, and metaphysical reflection. Her reappearance in the final arc as a catatonic survivor, and eventual awakening, complicates the narrative of loss.

Eva embodies the possibility of resurrection—not just biologically through the potential cure, but emotionally through reconciliation. Her revelation about having lost a daughter opens the door to the potential familial link with Sophie, a moment laced with ambiguity and grace.

Eva’s arc—from ideal to memory to reclaimed personhood—underscores the novel’s meditation on time, loss, and the fragile persistence of human connection.

Peau

Peau, the raven, serves as one of the most unique and symbolically rich characters in The Way. More than a mere animal companion, Peau is capable of rudimentary speech and complex perception, often acting as a guide, scout, and emotional mirror for Will and Sophie.

His language—a blend of mimicry and intuitive logic—provides a form of interspecies communication that challenges human exceptionalism. Peau’s intelligence and loyalty are often juxtaposed with a comic mischievousness, adding levity to an otherwise somber narrative.

His actions, especially summoning a flock of ravens to defeat Flynn, position him as a literal agent of justice and spiritual retribution. Peau also functions as a bridge between the human and natural worlds, reinforcing the novel’s themes of ecological renewal and the interdependence of all living beings.

In a world where civilization has failed, Peau represents a new form of alliance—pragmatic, spiritual, and deeply necessary.

Cassie

Cassie, the large, intelligent cat, is a quieter yet steadfast presence in Will’s journey. Unlike Peau, Cassie doesn’t communicate through language but expresses understanding through action and presence.

She represents comfort, intuition, and the embodied knowledge of the natural world. Cassie’s interactions with Peau, including their unusual mating episode, offer moments of unexpected humor and poignancy, reinforcing the novel’s blending of absurdity with emotional truth.

As a companion, Cassie anchors Will in the moment, providing a tactile sense of continuity and trust. Her survival, affection, and instincts contrast sharply with the predatory or indifferent forces of the post-apocalyptic wilderness, reminding readers that in the ruins of human dominance, gentler forms of intelligence endure.

Isabella

Isabella is a figure of ephemeral warmth and hard-won wisdom. A resident of the fortified town of Cottonwood, she offers Will a momentary sanctuary filled with emotional complexity.

Smart, pragmatic, and candid, Isabella exemplifies the resilience of those who have learned to survive within community rather than isolation. Her frank confession of early-stage Disease X and her openness to intimacy reflect a nuanced understanding of mortality and emotional immediacy.

She embodies the kind of transient yet profound connection that gives Will the strength to continue his journey. Through their brief relationship, The Way explores the interplay of sexuality, vulnerability, and mutual care in a world where the future is uncertain but the present moment can still be cherished.

Buck Flynn

Buck Flynn is the embodiment of menace and moral corruption in The Way. As the leader of the ARM militia, he is not merely a physical threat but a psychological one.

Described with pallid skin and fishlike eyes, Flynn carries an aura of otherworldliness, hinting at a possible metaphorical role as a figure of anti-life or corrupted evolution. His charisma is chilling, and his persistence in hunting Will underscores his symbolic function as a nemesis.

Flynn’s eventual downfall—mutilated by ravens and choosing suicide—serves as a powerful narrative resolution. He represents the lingering shadows of the old world: power without ethics, violence without purpose, and ego unchecked by conscience.

His death is not just a plot point but a narrative exorcism, clearing the way for renewal and peace.

David Marsh

David Marsh is the spiritual anchor of The Way, offering Will a sanctuary of philosophical and emotional restoration. As a hermit practicing Tibetan Buddhism, David challenges Will’s intellectual cynicism with metaphysical inquiry and serene presence.

His conversations with Will are dense with spiritual insight, often shaped by Buddhist koans and rituals that offer alternative frameworks for understanding suffering and compassion. David is both teacher and friend, guiding Will toward a more integrated sense of self and purpose.

Their shared ritual and emotional communion suggest that meaning can still be found—not through answers, but through the acceptance of paradox and presence. David’s role is crucial in reorienting Will’s moral compass, grounding the story in a spiritual dimension that complements its environmental and existential themes.

Pelageya

Pelageya, though a secondary character, represents the endurance of memory and the continuity of human relationships. Once a child known to Will, she is now the grown companion of David in the hermitage.

Her presence is emotionally resonant, a living reminder of the past who has evolved in solitude yet retained a core of humanity. Through her, Will is reminded that his actions and relationships ripple beyond the immediate, reinforcing the story’s meditation on continuity amidst collapse.

Pelageya offers no grand gesture or revelation, but her quiet, steadfast presence adds texture to the narrative and reinforces the theme of enduring connection.

Serena

Serena is a pragmatic survivor and caretaker of a fragile semblance of order in the town of Princely. As a madame overseeing a brothel, she negotiates power, protection, and commerce with shrewdness and humanity.

Her interactions with Will are marked by honesty and subtle emotional intelligence, especially when discussing Sophie’s future. Serena functions as both a foil and a mirror to Will—someone who has made compromises but continues to uphold a sense of dignity and protection.

In offering Will advice and helping to shield Sophie, Serena underscores the novel’s recognition that morality, in a broken world, often resides in the grey zones. Her strength and realism add a crucial dimension to the story’s examination of survival and ethical ambiguity.

Themes

Environmental Collapse and the Failure of Human Stewardship

Humanity’s abdication of responsibility toward the Earth is presented not as an isolated mistake but as a compounding series of ecological sins that resulted in near-total environmental devastation. The remnants of civilization—dead cities, poisoned landscapes, and genetically mutated wildlife—form a grim backdrop against which the characters move.

Will’s observations of how nature has begun to reclaim urban ruins with wild animals roaming freely through Santa Fe and Albuquerque draw attention to the resilience of the natural world and simultaneously underscore what was lost due to human arrogance. The tiger that intervenes in his favor, the rewilded bison herds, and even the appearance of camels in the desert all reflect an emerging new ecosystem, one no longer dominated by humans.

Yet there is no triumph in this renewal, only a mournful acknowledgment that this regrowth comes after the violent collapse of civilization. Will’s musings, particularly his guilt over scientific complicity and his reverence for animal intelligence, illustrate a deepening awareness that humanity’s belief in its superiority was a fatal misjudgment.

In this world, interspecies communication no longer seems a fantasy but a necessity, as cooperation across biological lines becomes essential to survival. This recognition does not romanticize nature—it remains perilous and unyielding—but it demands humility and respect.

The novel quietly indicts human consumption, greed, and technological overreach, suggesting that the real apocalypse was not a singular event but an ongoing cascade of negligence.

Grief, Memory, and the Persistence of Love

Will’s inner world is shaped by loss: of Eva, of civilization, of certainty, of self. His nightly letters to Eva—written with no expectation of reply and then ceremonially burned—are acts of desperate communication in a universe that has ceased to answer.

These letters are not just an expression of mourning, but a gesture of continuity, an insistence that love once experienced cannot simply vanish. The suggestion that Eva’s consciousness may still register these messages becomes a fragile lifeline for Will, who cannot surrender to a world stripped of metaphysical comfort.

His grief isn’t passive; it becomes a philosophical mode, propelling him to confront existential dread, especially the idea that death may mean obliteration. Yet it’s also through memory that Will finds strength.

Recalling the intimacy and intellectual bond he once shared with Eva, he connects past to present, and keeps alive a version of himself unbroken by collapse. Later, when Eva is discovered alive but catatonic, the possibility of her revival echoes the broader theme of love enduring in even the bleakest conditions.

Their eventual reunion reaffirms that emotional connection can survive where everything else has failed. Even the ambiguous suggestion that Sophie may be their daughter gives this theme generational weight, as Will becomes a surrogate father despite biology being uncertain.

In a world where identity and lineage have eroded, love—personal, remembered, or projected—remains one of the few stable forces.

Companionship and the Redefinition of Family

In the wake of societal collapse, traditional notions of family are upended. The bond between Will and Sophie evolves from wary alliance to something akin to father and daughter.

Initially bound by necessity, their relationship deepens through shared trauma, emotional disclosure, and acts of mutual protection. Sophie’s defensive use of violence to save Will, her vulnerability during illness, and their shared rituals—watching old films, sharing philosophical insights—forge an emotional intimacy that transcends survival.

Will’s relationship with his animal companions, particularly Peau and Cassie, also defies typical human-animal boundaries. Their intelligence, loyalty, and capacity for emotional engagement suggest a broader, more inclusive understanding of family that extends beyond species.

This radical empathy is not sentimental but hard-earned through shared suffering and daily reliance. Later, when Will, Eva, and Sophie stand on the threshold of forming a new familial unit, the text presents a poignant reframing: instead of emphasizing blood ties, it privileges chosen bonds and emotional authenticity.

Sophie’s invitation to “adopt” Eva and Will reflects an inversion of power structures and conventional roles, one grounded in mutual care rather than hierarchy. This reconstruction of family represents a rejection of the societal frameworks that collapsed and an embrace of relationships forged through compassion and choice.

Survival and Moral Ambiguity

Survival in The Way is never presented as a simple contest of strength. The characters constantly confront moral dilemmas that force them to navigate a crumbling ethical terrain.

Sophie’s shooting of a feral child to protect Will isn’t framed as heroism but as a deeply uncomfortable necessity. Will himself admits to causing harm despite his intentions to do good, and David Marsh’s spiritual teachings confirm that in a broken world, no action is without consequence.

Compassionate acts carry a cost, and the line between mercy and cruelty is often unclear. The militia group ARM, particularly Buck Flynn, represents unbridled survivalism—ruthless, dehumanizing, and violent.

Flynn’s charisma and near-mythical presence add a layer of symbolic menace: he is the face of power unmoored from conscience. In contrast, Will’s journey becomes a spiritual interrogation of what it means to remain ethical when systems of law and accountability have disappeared.

His use of Buddhist ritual, his protection of Sophie, his decision to share resources with Isabella—all are attempts to act justly in an unjust world. Yet the novel does not reward these choices with clear victories.

Instead, it offers glimpses of redemption, fleeting peace, and rare human connections that become, in their fragility, more precious than triumph. The message is not that virtue guarantees survival, but that morality—however fractured—is still worth pursuing, even when no one is watching.

The Role of Spirituality and Inner Transformation

Spiritual inquiry in The Way is not superficial. It becomes a structural and emotional foundation for the characters’ journey, particularly Will’s.

He oscillates between scientific pragmatism and Buddhist metaphysics, a duality that reflects the book’s broader exploration of rationality versus transcendence. Will’s spiritual practices—tsok rituals, sur offerings, meditative reflection—are not ornamental but central to his evolving worldview.

When Sophie falls ill, it is not technology but a ritual prayer and a wild plant (perhaps brought by Peau) that facilitates her recovery. While not presented as magical, this moment affirms that openness to the mysterious may be just as essential to survival as technical know-how.

David Marsh functions as a spiritual guide, leading Will through conversations that grapple with awareness, compassion, and the acceptance of imperfection. Their dialogue underscores a central paradox: that even in the face of destruction, consciousness itself may offer a kind of salvation.

This isn’t escapism; rather, it’s an attempt to reconcile the material and the immaterial, the seen and the unknown. As Will begins to make peace with his grief, his regrets, and his uncertainty, he experiences moments of serenity that suggest personal enlightenment is possible even amid societal ruin.

The spirituality in the novel is thus not prescriptive but experiential—born of suffering, humility, and love.

The Fragility and Resilience of Civilization

Throughout The Way, civilization is portrayed as a beautiful yet brittle construct, easily destroyed and difficult to resurrect. The remnants of the old world—the house in the hidden valley, Cottonwood’s micro-economy, Princely’s patchwork governance—are glimpses of what once was and what might be again.

These surviving outposts are fragile, their existence constantly threatened by disease, scarcity, or violence. Yet they also showcase human ingenuity and adaptability.

Cottonwood’s use of old currency, its communal mourning rituals, and its emphasis on shared labor all reflect a grassroots resilience built not from ideology but necessity. Similarly, Princely maintains infrastructure and trade through hard compromises.

Even the research community at the end, where electricity, medicine, and communication are preserved, depends on cooperation and discipline. But none of these places are ideal or immune to danger.

The novel is aware that attempts to rebuild society come with the risk of replicating old hierarchies and inequalities. The characters’ movement through these communities becomes a study in contrasts: between survivalist brutality and collaborative endurance, between opportunism and ethical cohesion.

Will and Sophie’s evolving relationships with these places suggest a cautious optimism. Civilization, the text implies, may not be permanently lost, but its future depends on a new ethos—one rooted in empathy, humility, and the acknowledgment of past failures.

The real test is not whether humanity can rebuild, but whether it can learn.