Untethered Summary, Characters and Themes | Angela Jackson-Brown

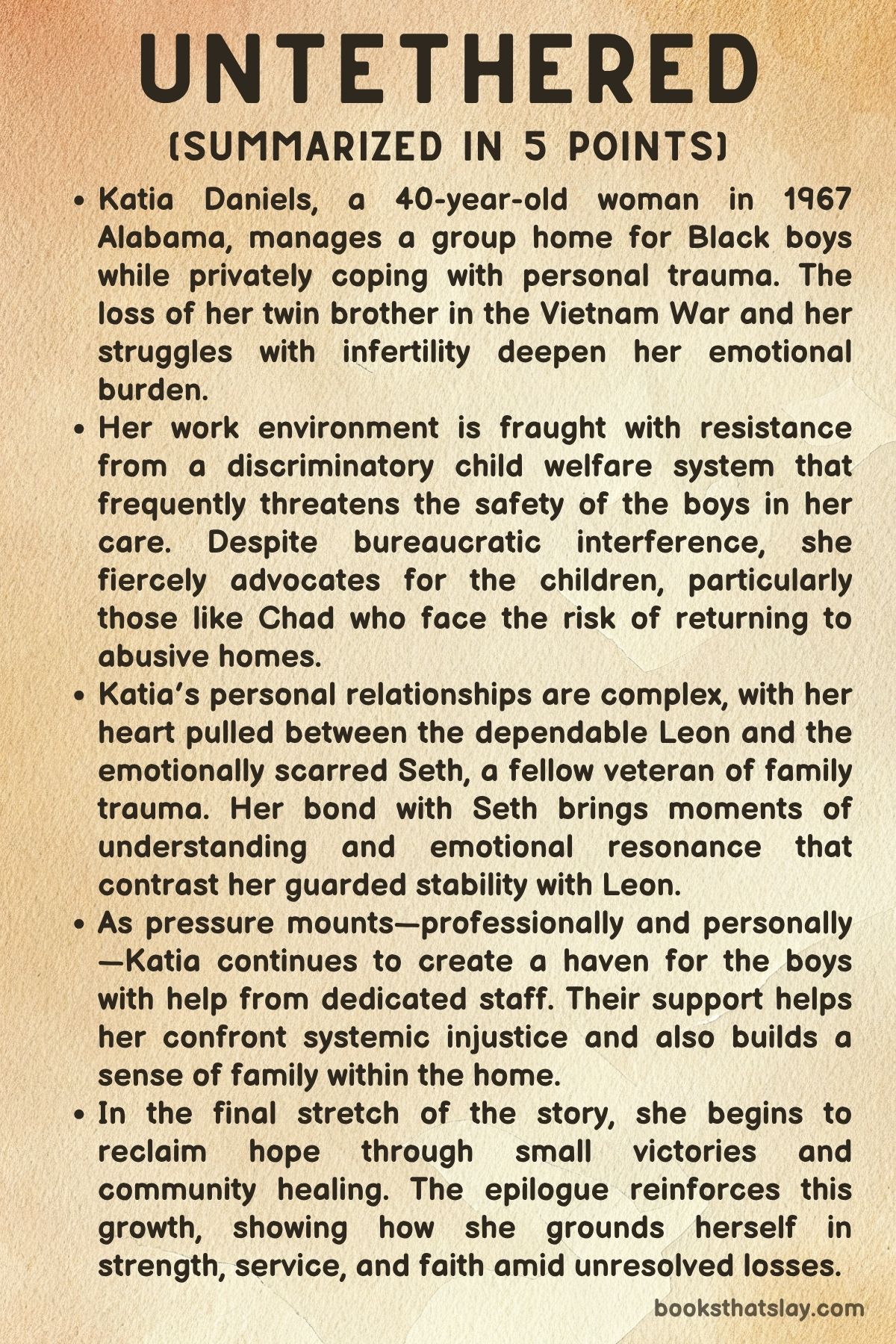

Untethered by Angela Jackson-Brown is a deeply emotional, socially resonant novel that follows Katia Daniels, the resolute director of a group home for Black boys in Alabama. Set in the turbulent 1970s, the story moves through themes of loss, motherhood, systemic failure, and emotional resilience, all grounded in Katia’s unshakeable sense of duty to the children in her care.

Navigating the aftermath of war, the wounds of racism, and the trauma inflicted by broken families, the novel paints an intimate portrait of how one woman strives to be a source of stability in a world that keeps unraveling. Through Katia’s eyes, readers witness both the heartbreak and triumph of everyday caregiving.

Summary

Katia Daniels begins her day weighed down by restless sleep and memories of her brothers, Marcus and Aaron, both of whom are serving in the Vietnam War. Her personal struggles, including infertility due to a recent hysterectomy, sit quietly beneath the surface, while her external world brims with responsibility.

As the executive director of the Pike County Group Home for Negro Boys, Katia finds herself at the center of constant emotional and logistical chaos. Her dedication to the boys is unyielding, especially when one of them, Chad, erupts in anger upon learning he might be returned to his neglectful and abusive mother.

Katia de-escalates the situation with practiced calm, revealing her skill not just as an administrator, but as a deeply empathetic protector. She insists Chad apologize and take responsibility for his outburst, but she also makes space for his fear and trauma, advocating for him in the face of a cold and bureaucratic caseworker named Mrs.

Gates.

Simultaneously, Katia is hit with devastating news: her twin brothers are now officially listed as missing in action. Though consumed by grief, she swallows her anguish to comfort her mother and maintain a sense of normalcy for the boys at the group home.

She channels her pain into routine—staff meetings, supervising activities, counseling sessions—all while trying to protect the fragile emotional ecosystems of children like Chad and Pee Wee. She finds a rare reprieve in music and solitude, letting herself briefly grieve to the sounds of Nina Simone.

Katia’s personal relationships are complicated. She is in a tentative courtship with Leon, a kind but emotionally distant man who seems more interested in companionship than passion.

Her mother encourages her to embrace Leon for the stability he offers, but Katia isn’t sure she can settle for something that feels so lukewarm. Her longing for deeper connection is further stirred when Seth Taylor, a former classmate and Vietnam veteran, reenters her life as a contractor hired to assess needed repairs at the group home.

Their chemistry reignites old feelings, but Katia’s internalized sense of brokenness—especially related to her infertility—makes her hesitant to pursue anything real.

As Thanksgiving approaches, Katia decides to bring Chad and Pee Wee home with her. It’s a bold move that flies in the face of official guidelines but stems from her understanding that holidays in the group home, while others leave to join their families, can be emotionally destructive for boys like Chad and Pee Wee.

Chad’s mother, Lena, only wants him back for the government benefits, and Pee Wee’s family is fractured and absent. Their excitement over plans like starting a chess club or watching Star Trek shows how hungry they are for normalcy and care.

These small moments of joy encourage Katia to believe her work, though emotionally taxing, is worthwhile.

Things begin to unravel when Marcus returns from Vietnam. Traumatized and withdrawn, he exhibits symptoms of severe PTSD.

He barely speaks and seems lost in his own mind. Seth, who understands the horrors of war firsthand, offers to talk to Marcus.

Their conversation becomes a turning point. Marcus opens up about the guilt he carries for not being able to save Aaron, revealing that his brother was lost in the jungle and possibly dead.

The confession is painful but also cathartic, and Marcus begins to reconnect with the family, especially his mother and Katia.

Thanksgiving dinner is a moment of warmth. The house is filled with relatives and laughter, and Chad and Pee Wee seem at ease, absorbed in the holiday festivities.

Seth’s presence is a quiet reassurance for Katia, and her cousin Alicia’s frank talk encourages her to seek a life filled with genuine love rather than compromise. But joy is always tempered by the threat of loss.

Chad’s court hearing is suddenly rescheduled, bringing the possibility of his forced return to Lena back to the forefront.

A new danger arises when Chad is confronted by Cobra, Lena’s violent boyfriend, at a local store. Cobra threatens Chad at knifepoint in front of a passive Lena, but Seth intervenes, saving Chad.

The trauma leaves Chad in near shock, and the situation worsens when the police handle the case with typical indifference. Chad confirms Cobra’s abuse, and the euphemistic term “dance” reveals the dark nature of his past exploitation.

Despite Katia’s efforts, Chad, fearing a return to his abusers, runs away. A desperate search yields no results, but local boys reveal that Cobra and Lena found and recaptured Chad.

Meanwhile, Pee Wee’s mother dies of a heroin overdose in prison. Though their relationship was distant, the news hits hard.

Katia arranges a funeral with her church community, creating a meaningful moment of closure and belonging for Pee Wee. The community, led by Pastor Bennett and Katia’s mother, rallies to make the service special.

Chad briefly calls Katia, confirming he is with Lena and Cobra, still in danger. The call ends abruptly, and Katia is left consumed by helplessness.

The situation leads to scrutiny from the group home board, and Katia is ultimately fired despite her years of tireless service. Only one member, Mrs.

Hendricks, supports her. Her dismissal is a blow, not just to her pride but to her identity as a caretaker and leader.

Seth comforts her, but Katia remains wary of emotional vulnerability. She shares her fear that being unable to have children makes her unworthy of romantic love.

Seth, however, sees her worth clearly and gently pursues her heart. In the meantime, a potential beacon of hope arrives when Pee Wee’s paternal grandmother, Mrs.

Staples, expresses interest in raising him. Katia facilitates the reunion, knowing it might finally provide him with lasting stability.

On her last day at the group home, former residents and staff surprise her with a heartfelt tribute—white roses, shared memories, and thanks. Though she is grieving her departure, she begins to reclaim a sense of hope and healing.

She travels to visit her cousin in Prichard, and Seth follows, bringing Nina Simone concert tickets and a sincere declaration of love. Katia lets her guard down, beginning a new chapter.

The epilogue offers closure and celebration. On Katia’s wedding day, Aaron—miraculously alive—returns home.

Pee Wee serves as the ring bearer, symbolizing the enduring love Katia poured into the children she considered her own. Surrounded by family and those she helped shape, Katia steps into a future built not on loss, but on love earned through resilience.

Characters

Katia Daniels

Katia Daniels stands at the emotional and narrative core of Untethered. As the executive director of the Pike County Group Home for Negro Boys, she is a portrait of unwavering devotion, quiet strength, and compassionate leadership.

Her daily life is a balancing act between personal anguish and the immense responsibility she shoulders at the home. Her internal world is defined by complex grief: the pain of a recent hysterectomy that ended her hopes of biological motherhood, the soul-wrenching loss of her brother Aaron in Vietnam, and the trauma of watching her other brother Marcus return home broken by the same war.

Yet Katia does not retreat from these wounds. Instead, she redirects her maternal instinct into nurturing the boys in her care, often defying institutional protocol in favor of emotional truth.

Her bond with Chad and Pee Wee reveals both her power and her vulnerability—she becomes a mother figure while constantly reminding herself of the impermanence of these attachments. Katia’s struggle with her feelings for Leon, a well-meaning but uninspiring suitor, and her rekindled emotions for Seth Taylor, a veteran with his own scars, underscores her deeper longing for a passionate, meaningful connection.

Even in the face of professional ruin and personal heartbreak, Katia retains her dignity and grace. Her departure from the group home is both a loss and a legacy, honored by the very community she fought so hard to protect.

Ultimately, her story is one of transformation: from sorrow to healing, isolation to belonging, and from quiet service to personal fulfillment.

Chad

Chad is perhaps the most tragic and emblematic figure in Untethered, embodying the cost of systemic neglect, familial abuse, and racialized trauma. From the moment he explodes in the group home upon learning he might return to his abusive mother, Chad reveals himself as a child on the edge—both emotionally volatile and deeply vulnerable.

His background is harrowing: a mother more concerned with government checks than his safety, and a violent, sexually abusive stepfather figure named Cobra. Chad’s yearning for love and stability clashes with his ingrained distrust, making his emotional breakthroughs with Katia especially poignant.

He goes from rage to remorse, from silence to confession, and from despair to hope under her guidance. Yet his story is not one of simple redemption.

After being forcibly reclaimed by his abusers, Chad’s eventual return to the home is short-lived. The trauma he carries culminates in his tragic shooting, a devastating blow not only to the group home but to the heart of the novel itself.

His death exposes the brutal realities of a system that fails its most vulnerable, despite the best efforts of individuals like Katia. Chad’s legacy lives on in the boys he inspired, in Pee Wee’s fierce loyalty, and in the community’s collective grief.

His character reminds readers that resilience and fragility often coexist, and that even the strongest displays of courage can be silenced by a world indifferent to Black suffering.

Pee Wee

Pee Wee, the youngest and most emotionally transparent of the boys, offers a profound emotional counterbalance in Untethered. He is sensitive, eager for affection, and intensely loyal—particularly to Chad, whom he regards as a brother.

His reactions are visceral and childlike: when his mother dies of a heroin overdose, he grieves deeply despite their estranged relationship; when Chad is killed, his devastation is total. Pee Wee’s heartbreak is made even more poignant by his repeated experiences of abandonment.

His story is shaped by systemic failure and family breakdown, yet he remains hopeful, clinging to moments of joy like chess games and holiday plans. His bond with Katia becomes increasingly maternal, a relationship that comforts him even as it strains Katia’s boundaries.

The arrival of his paternal grandmother, Mrs. Staples, introduces a long-awaited possibility for a stable home, and Pee Wee’s reluctant yet hopeful acceptance of this new family marks a turning point.

His growth is not marked by dramatic transformation but by small victories: grieving openly, accepting love, and daring to believe in permanence. Pee Wee’s vulnerability is his strength, making him one of the most emotionally resonant characters in the novel.

Marcus Daniels

Marcus Daniels, Katia’s surviving twin brother, returns from Vietnam a ghost of himself—traumatized, silent, and emotionally paralyzed by survivor’s guilt. His condition reflects the often-overlooked emotional toll of war, especially for Black veterans who return to a country that neither understands nor adequately supports their trauma.

Marcus is trapped in a psychological limbo, haunted by the loss of Aaron, his twin, whom he could not save. His eventual breakthrough—facilitated by Seth’s military camaraderie and gentle persistence—reveals a man desperate for absolution but unsure he deserves it.

Marcus’s confession about failing to rescue Aaron is heartbreaking, yet it becomes a moment of catharsis, especially when Katia and their mother receive his grief with unconditional love. His healing journey is slow but redemptive, and by the novel’s end, he begins to reclaim fragments of himself, attending Katia’s wedding and rejoining his family with tentative hope.

Marcus’s arc underscores the deep psychological wounds of war and the necessity of community, family, and vulnerability in the path toward recovery.

Seth Taylor

Seth Taylor is both a literal and emotional builder in Untethered. A Vietnam veteran and skilled contractor, Seth enters the story as a man capable of mending broken things—walls, relationships, and psyches alike.

His reappearance in Katia’s life is unexpected yet timely, rekindling old feelings while offering new emotional possibilities. Seth carries his own trauma from the war, yet unlike Marcus, he has channeled his pain into action, using his experiences to connect with others who suffer silently.

His ability to reach Marcus when no one else can is a testament to his emotional intelligence and patience. With Katia, Seth represents a future that is both tender and grounded, a sharp contrast to the emotionally tepid Leon.

His confession of love and gift of Nina Simone concert tickets mark a turning point in Katia’s emotional openness. Seth is not just a love interest but a symbol of mutual healing, proving that damaged people can still forge whole, meaningful relationships.

His presence in the novel is steadying, warm, and ultimately redemptive.

Leon

Leon is a gentle, well-meaning man who serves as a foil to Seth and a mirror to Katia’s emotional state. Their relationship is built on routine and expectation rather than passion and understanding.

Leon’s affection for Katia is sincere but lacks depth, and his inability to connect with her on a soulful level gradually becomes apparent. He represents the kind of life Katia could have if she chose safety over fulfillment.

Her reluctance to fully commit to Leon, despite pressure from her mother, reflects her growing insistence on emotional authenticity. Leon’s quiet dignity in the face of Katia’s eventual emotional drift is notable—he is not vilified but gently set aside as Katia pursues a more genuine connection.

His character, though less prominent, enriches the narrative by highlighting the difference between surviving and truly living.

Lena

Lena, Chad’s mother, is a tragic figure steeped in self-destruction and systemic failure. Drug-addicted, emotionally absent, and dangerously manipulative, Lena nonetheless evokes complex emotions.

Her neglect of Chad is criminal and heartbreaking, yet it’s clear she too is a product of generational trauma and poverty. Her dependence on Cobra for survival, despite his abuse of her son, reflects a harrowing lack of agency.

Lena’s feeble attempts at maternal care are overwhelmed by her addiction and desperation. Her inability to protect Chad—and her complicity in his suffering—casts a long shadow over the narrative.

Lena’s character functions as both a cautionary figure and a symbol of the broader societal neglect that enables cycles of abuse.

Cobra

Cobra is the clearest antagonist in Untethered, representing the violent, predatory force that stalks many children failed by the system. His abuse of Chad, particularly the euphemistically referenced “dances,” adds a chilling undercurrent of sexual violence to the narrative.

Cobra is a predator who thrives in the shadows of Lena’s addiction and the blind spots of institutional oversight. His control over Chad is both physical and psychological, and his threats escalate to the point of murder.

Cobra’s role in the story is harrowing and necessary, a brutal reminder of the stakes Katia faces in her work. His presence fuels the narrative tension and anchors Chad’s trauma in a terrifying, real-world evil.

Jason

Jason, the assistant director at the group home, is a steady, empathetic presence who rises to greater prominence after Katia’s dismissal. His background as a youth pastor informs his approach—he is patient, reflective, and deeply invested in the boys’ well-being.

His ability to share his grief and anger with Pee Wee after Chad’s death strengthens his role as a compassionate authority figure. Katia’s trust in him to lead the home after her departure is one of her final, most meaningful decisions.

Jason represents continuity and hope, proof that the values Katia upheld will endure in her absence.

Mrs. Gates

Mrs. Gates, the caseworker, is the embodiment of bureaucratic rigidity and emotional detachment.

Her antagonism toward Katia and her insensitive handling of Chad’s situation exemplify the systemic indifference that often undermines real care. She values procedure over people, and her presence forces Katia to fight harder for the boys.

Mrs. Gates is not a villain in the traditional sense, but a representation of how institutions often perpetuate harm through callousness and conformity.

Mama (Katia’s Mother)

Mama is the emotional backbone of Katia’s family. Strong, devout, and nurturing, she provides a moral compass and a source of comfort, particularly during Marcus’s return and Pee Wee’s loss.

Her belief in faith, family, and resilience anchors the narrative. Mama’s influence extends beyond her own children, as she helps organize Pee Wee’s mother’s funeral and brings the community together in moments of crisis.

She represents generational strength and the quiet power of maternal love, passing down to Katia the values that shape her caregiving ethos.

Themes

Maternal Identity Beyond Biology

Katia Daniels embodies a profound form of motherhood that defies conventional definitions. Though she is biologically unable to bear children due to a hysterectomy, her nurturing of the boys at the group home becomes a deeply maternal act, steeped in love, responsibility, and emotional labor.

The emotional resonance of her relationship with Chad, particularly when he wishes aloud that she were his mother, is a heartbreaking affirmation of her role as a caregiver. Katia experiences this longing as both validation and sorrow—a reminder of what she biologically cannot have and yet already possesses in an alternate form.

Her ability to de-escalate Chad’s violent outburst through compassion and firm discipline further reflects her intuitive parenting style, one grounded in emotional intelligence and moral guidance rather than blood ties. This nontraditional motherhood is challenged by institutional protocols and bureaucratic coldness, but Katia persists, taking emotional and professional risks to ensure the boys feel loved and seen.

Her ultimate decision to take Chad and Pee Wee home for Thanksgiving, despite knowing it might jeopardize her standing, exemplifies her prioritization of emotional healing over rules. Even in the face of professional fallout, she embraces the maternal role with integrity and courage.

Her infertility becomes less a symbol of lack and more an emblem of resilience, as she transforms her loss into a wellspring of care that redefines what it means to mother. Through Katia, Untethered reclaims motherhood from biology and elevates it as a deeply chosen, lived commitment rooted in love, sacrifice, and unrelenting presence.

Racialized Institutional Neglect

The novel exposes the systemic failures that plague Black children in care, highlighting how institutions often become sites of abandonment rather than refuge. Katia must navigate a social services system that prioritizes paperwork and policy over human need, as seen in her clashes with caseworker Mrs.

Gates and the insensitive police response after Chad is traumatized by his mother’s boyfriend. These structures, ostensibly created to protect, instead retraumatize already vulnerable children.

The boys’ experiences—ranging from physical abuse to emotional desertion—are met with indifference or hostility by professionals who lack cultural understanding or emotional sensitivity. Katia’s interventions become acts of resistance against this callous machinery.

Her advocacy for Chad after Cobra’s attack, her delicate handling of Pee Wee’s grief, and her refusal to turn away from boys like Darren and Charlie, who arrive with new traumas, illustrate how she compensates for a broken system with her own moral compass. But even Katia is not immune to its repercussions—she is eventually fired despite years of dedication, a stark reminder that the institution values liability management over the irreplaceable human bond she nurtured.

The narrative reveals how racism, bureaucracy, and neglect intersect to create a dangerous environment for Black youth, particularly boys, who are criminalized or discarded instead of supported. In Untethered, the group home becomes both a battleground and a sanctuary, and Katia’s efforts to humanize care stand in painful contrast to the apathy and prejudice surrounding her.

Grief, Trauma, and the Search for Emotional Restoration

Loss permeates every layer of Untethered, shaping characters’ behaviors, choices, and emotional landscapes. Katia grapples with the disappearance of her brother Aaron and the psychological unraveling of Marcus, whose return from Vietnam introduces a harrowing embodiment of survivor’s guilt and PTSD.

Their mother’s grief is raw and generational, folding Katia into a family system straining under the weight of war and unresolved trauma. This grief is mirrored in Chad and Pee Wee, who mourn not only absent parents but also the fantasy of normalcy and safety that every child deserves.

Pee Wee’s heartbreak at the death of his incarcerated mother—complicated though their relationship was—underscores the unresolved pain that shadows many of the boys. Chad, in turn, carries the scars of sexual abuse, betrayal, and maternal abandonment, each act of violence etching deeper wounds into his psyche.

His eventual murder is not just a tragedy but a culmination of compounded failure—by his family, the system, and the world that should have protected him. Yet, within this maelstrom, there are flickers of healing.

Seth’s patient engagement with Marcus allows for a rare moment of catharsis; Pee Wee’s funeral for his mother becomes a ritual of belonging and recognition. Katia’s continued vulnerability and emotional presence serve as a stabilizing force, making space for sorrow to be expressed rather than suppressed.

Grief in Untethered is omnipresent, but it is also transformative—it urges characters to fight harder for one another, to love more openly, and to believe that some healing, though partial, is still possible.

The Moral Cost of Caregiving

Katia’s journey is defined by the exhausting and often unacknowledged labor of emotional caregiving. Her role demands constant vigilance, empathy, and decision-making, with little institutional support and frequent personal sacrifices.

She is expected to be a mother figure, a therapist, an administrator, and a shield against the outside world—all without faltering. This labor takes an undeniable toll.

Her sleepless nights, the strain in her romantic life, and her suppressed grief are all symptoms of a woman pushed to her emotional brink. Katia’s professional and personal identities blur dangerously, especially as she takes risks that contravene policy in order to fulfill what she sees as her moral duty.

The moral ambiguity of her actions—such as secretly housing the boys during the holidays or delaying official procedures after traumatic events—is acknowledged but never condemned. Instead, these moments reveal the complexity of ethical caregiving in a broken system.

Her eventual firing, despite her successes, represents the institutional punishment for emotional labor that disrupts protocol. The novel questions what it costs to care so deeply in a world that prefers detachment.

Katia’s caregiving is radical in its refusal to abandon, to overlook, or to disengage. Her quiet, relentless efforts are contrasted with the passive or harmful actions of others—police officers, board members, distant parents—who shirk responsibility.

Untethered positions caregiving as both heroic and unsustainable, a force that sustains life but threatens to consume the giver. It asks not whether care is worth the cost, but why the burden must fall so heavily on those least supported.

The Quest for Personal Fulfillment Amid Duty

Katia’s story is not only one of service but also of longing—a yearning for romantic connection, emotional peace, and self-fulfillment that often gets deferred. Her relationship with Leon is tepid, defined more by obligation and familiarity than passion or mutual inspiration.

Her attraction to Seth introduces a complexity she hasn’t allowed herself to explore in years—a reminder of her own desires as a woman, not just a caregiver or professional. Yet she hesitates, fearing rejection due to her infertility and questioning whether she deserves a life that centers her needs.

This internal conflict is furthered by societal and familial pressures—her mother’s insistence that time is fleeting and that companionship, even if imperfect, is a blessing not to be refused. But Katia resists settling.

Her life has been defined by sacrifice, and she craves a connection that is affirming rather than dutiful. The eventual progression of her relationship with Seth, culminating in marriage, marks a reclaiming of self—a deliberate step toward choosing joy, despite the losses that have defined her.

Even her decision to leave the group home with dignity and belief in Jason’s leadership reflects a shift from obligation to intentionality. Katia’s narrative arc is not one of romantic fantasy but of hard-earned clarity.

Untethered asserts that fulfillment is not antithetical to service; rather, it must coexist with it. Katia learns to hold space for both—to nurture others without erasing herself, to mourn what she cannot have while reaching for what she can still build.