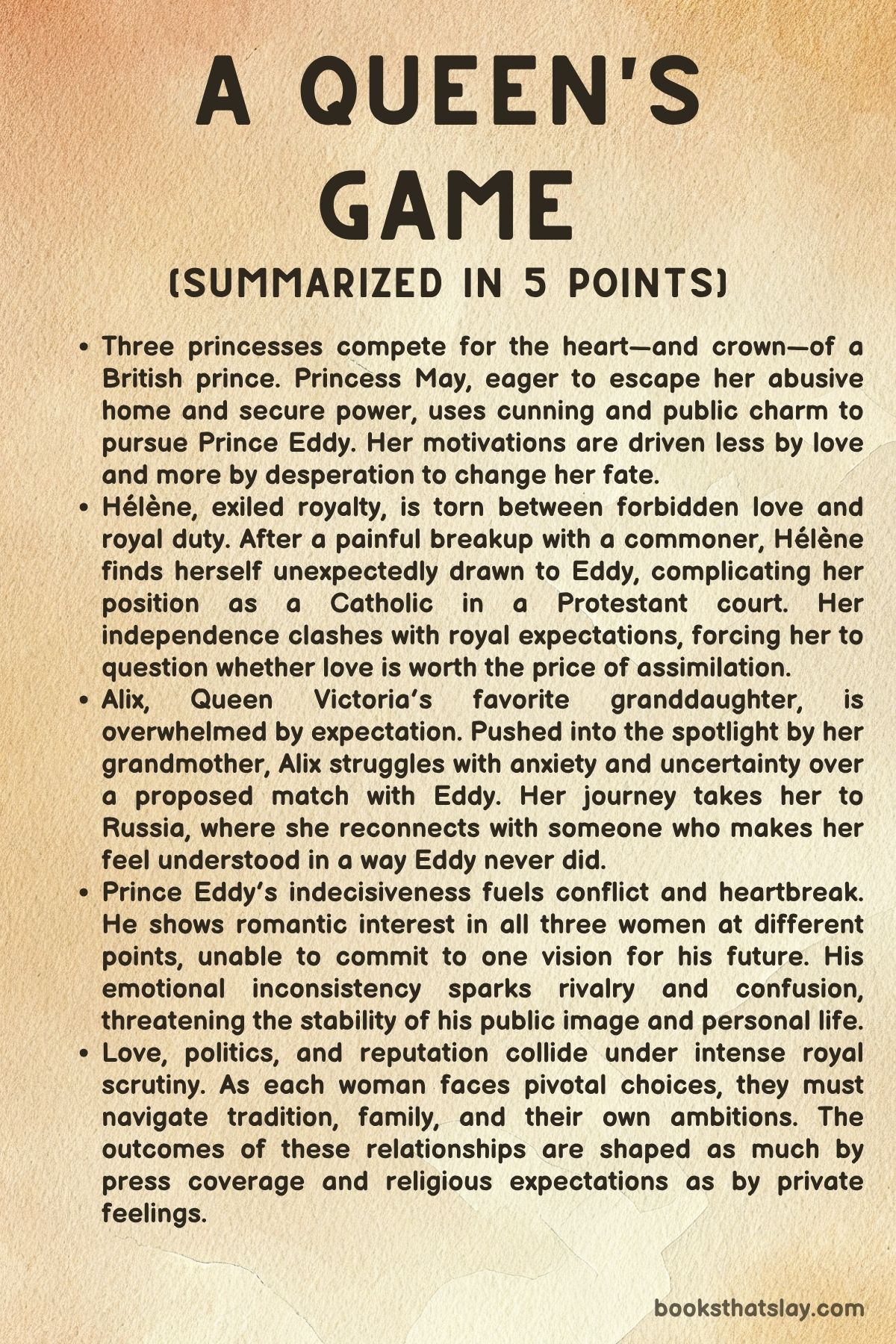

A Queen’s Game Summary, Characters and Themes

A Queen’s Game by Katherine McGee is a rich, character-driven historical novel that follows three young women navigating the elaborate and often unforgiving world of European royalty in the late 19th century. Set against the lavish backdrop of grand estates, political matchmaking, and strict societal expectations, the novel traces the intersecting lives of May of Teck, Princess Hélène d’Orléans, and Princess Alix of Hesse.

Each woman must contend with the limitations of her station, the pursuit of love, and the subtle strategies required to secure a place in a world where appearances mean everything. The story explores agency, ambition, and personal sacrifice with depth and elegance.

Summary

In A Queen’s Game, Katherine McGee immerses readers into the complex and emotionally layered lives of three royal women—May of Teck, Hélène d’Orléans, and Alix of Hesse—as they maneuver through the harsh realities of aristocratic life in late 19th-century Europe. Their journeys are shaped by social politics, arranged marriages, personal yearnings, and the overarching influence of Queen Victoria, whose strategic decisions loom over them all.

May of Teck, lacking a fortune and considered neither beautiful nor powerful enough to attract a desirable suitor, finds herself in a precarious position. Her hopes of marrying into prominence are continually dashed by her middling royal status.

After being spurned by John Hope, who chooses a younger woman, May grows increasingly desperate. Her sharp instincts lead her to manipulate a budding courtship between her cousin Alix and Prince Eddy, the future heir to the British throne.

May visits Alix under the guise of cousinly affection, subtly sowing seeds of doubt about Eddy’s character. Her goal is survival through elevation, not cruelty, and this calculated move reflects her growing willingness to use deception to secure her future.

Hélène d’Orléans stands in stark contrast to May. Though royal by birth, her family’s exile from France renders her title largely symbolic.

A free spirit who rejects societal constraints, Hélène indulges in a passionate affair with Laurent, her family’s coachman. The relationship, however, ends in disappointment when Laurent refuses to let her accompany him to France.

His departure underscores the limits of her romantic idealism. Reeling from heartbreak, Hélène seeks physical freedom, galloping through a storm on horseback only to crash and be rescued by Prince Eddy.

This unexpected interaction leads to a moment of vulnerability and attraction between them. When Eddy later proposes courtship, Hélène discovers that she is a replacement for Alix, a realization that deepens her emotional wounds and illustrates how even rebellious women are ensnared by royal machinations.

Meanwhile, Alix of Hesse is thrust into a politically advantageous engagement with Prince Eddy, orchestrated by Queen Victoria. Although admired for her beauty and grace, Alix suffers quietly under the weight of her responsibilities.

She does not love Eddy and is haunted by personal trauma, including guilt over her brother’s death. May’s veiled warnings about Eddy’s behavior unsettle her further.

Alix longs for an authentic life, not one dictated by pageantry and control. Despite immense pressure from the Queen, including a forced public declaration of engagement, Alix resists.

She later travels to Russia to visit her sister and meets Nicholas, the tsarevich. His gentleness and introspective nature provide a stark contrast to Eddy’s passive conformity.

The connection between Alix and Nicholas is subtle but promising, hinting at a future relationship grounded in mutual understanding rather than obligation.

As the narrative progresses, the emotional and political tensions intensify. Hélène, nursing her wounds from Laurent and the complexities surrounding Eddy, finds herself drawn to him again.

Their second interaction is emotionally charged but ultimately inconclusive, as Eddy’s loyalties are pulled in multiple directions. At the same time, May continues to wrestle with rejection and ambition.

Her interactions with the brash American heiress Agnes Endicott highlight her inner conflict between propriety and self-assertion. May’s budding alliance with Agnes opens new possibilities for her social standing but also reminds her of her precarious position.

A pivotal moment occurs during Queen Victoria’s orchestration of an official engagement between Eddy and Alix. Neither party is emotionally ready, yet they are cornered into compliance.

Alix’s sense of entrapment grows stronger. A heartfelt letter from Nicholas congratulating her on the engagement, sent before any public announcement, pushes her to clarify her feelings.

She writes back to say no such commitment has been made, signaling her inner defiance. Meanwhile, May witnesses a private moment between Eddy and Hélène at Balmoral and realizes the truth of their affections.

This revelation strikes a blow to her ambitions, though it also grants her new perspective on her place within the royal chessboard.

The tension culminates during a grand costume ball in London, where Alix is stunned by the surprise appearance of Nicholas. Their private conversation in the garden becomes a turning point.

Alix confesses she is not engaged, and Nicholas, emboldened by this revelation, kisses her. This moment signals the birth of a relationship based on genuine connection.

Concurrently, Eddy confronts Hélène in the orangerie and proposes an elopement, pleading for a future unbound by royal expectations. Hélène, though moved, declines.

Her decision is rooted in realism: love is not enough to escape the prison of birthright.

May’s transformation becomes most evident in the novel’s final segments. After confronting Agnes about her manipulative behavior and discovering her father’s cruelty during the royal wedding, May is forced to reevaluate her role in society.

Her father’s disdain and emotional abuse spark a fierce determination in her. She begins to channel her pain into ambition, no longer hoping merely to be accepted but to rise above everyone who dismissed her.

Even when George, Eddy’s brother, becomes romantically entangled with another woman, May does not succumb to despair. Instead, she sharpens her focus and returns her attention to Eddy, seeing him now not as a prize of affection but as a means of ascending the hierarchy.

Hélène, now bruised from her romantic losses, finds solidarity with Alix in a rare moment of female camaraderie. They smoke and share confidences outside the palace, both recognizing the need for strategic action.

Alix encourages Hélène not to play fair against May, who has already demonstrated a willingness to fight dirty. The two women, long isolated by rivalry and expectation, find common ground in their struggles, and their brief alliance signals a shift in the power dynamics between them.

By the end of the book, all three women have evolved dramatically. May has emerged from her emotional devastation as a calculating and self-possessed contender.

Hélène has abandoned romantic idealism for a harder-edged realism, steeled by friendship and purpose. Alix, once passive and doubtful, has found a possible future rooted in mutual respect and emotional depth with Nicholas.

Each woman has been reshaped by her experiences—not broken, but transformed, and now prepared to take ownership of her fate in a world that never intended to give her any.

Characters

May of Teck

May of Teck emerges as a fiercely determined yet emotionally battered figure navigating the tightrope of late 19th-century aristocratic society. Lacking a substantial dowry, political clout, or remarkable beauty, May has long endured the sting of rejection and societal indifference.

Her early appearances showcase a woman who has internalized her limitations, yet refuses to surrender to them. Rather than wallow in despair, she exhibits a pragmatic intelligence—keenly observing those around her and exploiting opportunities, however fleeting.

Her ambition is palpable, most notably in her subtle sabotage of Alix’s potential match with Prince Eddy. While her actions may seem manipulative, they are born of survival rather than malice, revealing a woman who is calculating not for cruelty’s sake, but out of sheer necessity in a world that offers her little room for error.

As the narrative progresses, May undergoes a compelling transformation. The betrayal by Agnes, whom she had considered a friend, strips away her lingering innocence about social alliances.

Her father’s verbal abuse during the royal wedding becomes a defining moment—crushing yet clarifying. No longer content to seek validation through romantic or paternal approval, May begins to harness her anger as motivation, directing it toward a clear vision of autonomy and power.

Her reaction to seeing George with Missy reflects the final shattering of her fantasies; instead of retreating, she becomes more resolute, setting her sights once again on Prince Eddy. This evolution—from a sidelined royal to a woman of ruthless ambition—marks her as one of the most complex and compelling characters in A Queen’s Game.

Hélène d’Orléans

Hélène d’Orléans is introduced as a woman unafraid to push against the boundaries of decorum, driven by a passionate desire for freedom and self-definition. Though technically royalty, her family’s exile renders her title largely symbolic, which only deepens her sense of marginalization.

She resists the suffocating constraints of noble life through her affair with Laurent, a coachman, whose departure underscores the disparity between her dreams and reality. Her heartbreak is not just romantic—it is existential.

Laurent’s rejection strips her of the illusion that love alone can liberate her from the roles she is forced to play. Her wild ride into the storm following his departure symbolizes a rebellious spirit colliding with the physical and emotional limits imposed by society.

Yet, Hélène’s story is far from one of defeat. Her interactions with Prince Eddy, particularly after being rescued during the storm, offer a glimpse into her vulnerability and craving for connection.

However, even here, she is disillusioned—Eddy sees her as a substitute, not as a singular beloved. Her eventual refusal of Eddy’s proposal to elope, despite her deep feelings for him, underscores a mature awareness of reality.

She does not succumb to romantic idealism but instead recognizes the futility of attempting to escape her fate through impulsive love. Later, her candid conversations with Alix mark a shift toward strategic self-preservation and camaraderie.

Encouraged to abandon noble restraint and fight back against May’s underhanded schemes, Hélène readies herself not as a victim, but as a contender. Her arc reveals a character who embraces resilience, intelligence, and emotional fortitude in a world that offers her neither shelter nor fairness.

Princess Alix of Hesse

Princess Alix of Hesse is a portrait of internal conflict and quiet defiance. Unlike May or Hélène, Alix is not openly ambitious or rebellious.

Her struggle is deeply psychological, rooted in childhood trauma, anxiety, and a profound discomfort with the performative aspects of royalty. Alix’s beauty and royal pedigree make her an ideal match in the eyes of Queen Victoria, yet her heart and mind are not easily molded.

When faced with Prince Eddy’s courtship, Alix is visibly distressed—not by Eddy himself, but by the machinery of royal matchmaking that devalues love and volition. Her response to Queen Victoria’s manipulation at Balmoral reveals her mounting internal rebellion.

Though she is often silent, her silence is not passivity—it is resistance forged through endurance.

Alix’s emotional world comes further into focus through her evolving relationship with Nicholas, the tsarevich of Russia. In him, she finds a potential partner who appreciates her intellect and emotional depth, offering her a vision of love that is neither transactional nor hollow.

Her correspondence with Nicholas reveals her yearning for authenticity and emotional safety, in contrast to the performative affection expected of her with Eddy. Alix’s strength becomes most apparent in moments of psychological collapse, such as her breakdown at the opera—moments that expose her vulnerability but also her capacity for renewal.

Her late-night conversation with Hélène, where she encourages a less forgiving strategy against May, shows her growing willingness to play the game she so despises. In the end, Alix is a character defined not by overt rebellion but by the persistent, quiet assertion of her right to choose—a right so often denied to women like her.

Prince Eddy

Prince Eddy is a character shaped by duality: he is both a symbol of imperial obligation and a man struggling to assert emotional authenticity in a world that scripts his every move. Initially portrayed through others’ perspectives, Eddy seems pliant and aloof, allowing Queen Victoria to dictate the terms of his romantic engagements with little resistance.

His vacillation between Alix and Hélène exemplifies a man torn between duty and desire, passively navigating a life overdetermined by protocol. His behavior at Balmoral, including his hesitant agreement to delay the engagement to Alix, reflects a lack of personal conviction more than calculated deceit.

Yet glimpses of Eddy’s emotional depth emerge through his relationship with Hélène. His rescue of her during the storm, their tender exchange, and his eventual plea for elopement display a man capable of genuine feeling—if not decisive action.

Eddy’s proposal to Hélène, made in secret and against all societal expectation, represents a rare act of courage. However, the fact that Hélène refuses him also speaks to Eddy’s limitations; he cannot promise a future free of royal burdens.

When Hélène departs, his heartbreak is genuine, but his return to duty feels inevitable. Eddy’s character is ultimately defined by tragedy—he is a man caught between two women, two futures, and two selves, unable to fully realize any of them.

In A Queen’s Game, he is less a romantic hero and more a poignant reminder of how monarchy crushes even those who appear to wield its power.

Agnes Endicott

Agnes Endicott is the social climber par excellence—bold, unapologetic, and ruthlessly strategic. An American heiress with no royal title but a sharp sense of opportunity, she understands the transactional nature of aristocratic society better than most born into it.

Her initial friendship with May is one of calculated generosity; she showers May with favors not out of affection, but to secure a foothold in elite society. Agnes’s manipulation of May—pretending friendship while secretly orchestrating matches for herself and positioning May as a convenient intermediary—reveals a deep cunning masked by charm.

When May confronts her, Agnes defends her actions as pragmatism, not betrayal, exposing her belief that in the game of status and survival, sentiment is a luxury. Her character serves as a critique of the hollow alliances that underpin aristocratic society, where women like Agnes weaponize vulnerability and generosity as tools of ascent.

Yet, there is also a glimmer of respect in how she pushes May to see the harsh realities of their world. Agnes may be ruthless, but she is never naive.

Her role in A Queen’s Game is vital not only as a foil to May’s earlier innocence but also as a representation of how outsiders—clever, marginalized, ambitious—can upend established hierarchies. She is both villain and visionary, a disruptor whose presence forces others to reckon with the cost of ambition.

Themes

Female Agency in a Patriarchal Society

The central narrative of A Queen’s Game reveals the persistent and multifaceted struggles of royal women to assert control over their lives within the rigid hierarchies of late 19th-century European aristocracy. Each woman—May, Alix, and Hélène—encounters circumstances where personal will is either dismissed or weaponized against them.

May’s calculated attempts to maneuver herself into advantageous positions, especially with Prince Eddy, stem not from ambition alone but from sheer necessity. She is acutely aware of how little power she possesses as a minor royal without wealth or beauty.

Her actions—sabotaging Alix’s potential match, confronting Agnes, confronting her father—are all rooted in a burning need for self-determination in a society that denies her value. Alix, despite her proximity to power, often finds her voice stifled, whether by Queen Victoria’s impositions or the mechanical rituals of courtship and expectation.

Her growing bond with Nicholas offers the first glimmer of choice in her life, but even this potential freedom is fraught with the weight of external pressures. Hélène, arguably the boldest of the three, attempts to rebel through romance and independence, yet faces the crushing truth that her passions cannot undo the class boundaries that bind her.

The theme of agency is portrayed not as a quest for complete liberation—an impossibility in this context—but as a relentless negotiation between compliance and resistance. These women push against their constraints, not always successfully, but with a remarkable clarity about what is being taken from them and what they must fight to reclaim.

Love as Transaction and Illusion

Romantic entanglements in A Queen’s Game serve less as fulfilling unions and more as battlegrounds where affection is routinely sacrificed at the altar of political expediency or personal survival. Alix’s courtship with Prince Eddy is not born of affection but engineered by Queen Victoria as a matter of dynastic strategy.

Her reluctance, Eddy’s passivity, and the Queen’s high-handed declaration of their engagement expose the performative and coerced nature of royal love. Hélène’s relationships are marked by emotional idealism clashing against bitter disillusionment.

Her affair with Laurent, a coachman, momentarily promises an escape from the trappings of royalty, only to reveal itself as a painful imbalance in affection and power. Her later involvement with Eddy brings her into direct confrontation with the mechanisms of royal matchmaking, where love must be hidden, denied, or forfeited to maintain appearances.

Even May, who is not romantically idealistic, becomes entrapped by false hope—first with John Hope, then George, and finally in her strategic sights on Eddy. What connects all these arcs is the realization that love, in this world, is rarely tender or reciprocal.

It is politicized, weaponized, and ultimately mistrusted. Whether one seeks it earnestly like Alix and Hélène, or manipulates it like May, romantic love functions more as a fragile illusion or a social currency than a safe refuge.

This theme underscores how deeply compromised emotional connections become when individual desires must always answer to external expectations.

Power Through Performance and Deception

In a society where women cannot claim political or economic power outright, the pursuit of influence in A Queen’s Game becomes an exercise in social performance and strategic deception. May embodies this approach most clearly, recognizing that her survival depends on her ability to play roles others expect while secretly engineering her own ascent.

Her interactions with Alix, Agnes, and Eddy are rarely straightforward. She studies their weaknesses, leverages secrets, and reconfigures herself depending on what the moment requires.

But this performance is not limited to May alone. Hélène, too, learns the cost of vulnerability and begins to reshape her approach after Alix encourages her to fight strategically rather than honorably.

Even Alix, usually governed by sincerity and restraint, begins to understand that staying silent and proper won’t protect her from the emotional manipulations of those around her. By the end, all three women are forced to become actresses in their own lives—calculating what truths to reveal, what emotions to conceal, and what strategies to pursue.

Deception becomes a survival tactic, not out of malice, but because the world they live in demands it. Their performance is not an abandonment of authenticity, but a grim necessity in an environment that rewards appearances over integrity.

This theme highlights the ways power can be seized, not through official titles, but through calculated expressions of charm, information, and emotional leverage.

Female Solidarity and Fractured Alliances

While rivalry and manipulation are present throughout the story, A Queen’s Game also captures moments of profound solidarity among the women, offering glimpses of connection and empathy amidst the competition. The relationship between Hélène and Alix, in particular, shifts from mistrust and confrontation to a deep, emotional understanding.

When Alix comforts Hélène during her heartbreak and later urges her to be tactical against May, it marks a turning point in their relationship—one where honesty and mutual respect take precedence over social niceties. These moments are rare but deeply impactful, revealing how women in a repressive system can sometimes offer each other strength where society offers only confinement.

However, the theme of solidarity is complicated by betrayal, competition, and ambition. May and Agnes begin as allies, but their friendship is revealed to be one-sided and opportunistic.

May’s feelings of betrayal drive her transformation and harden her approach to relationships moving forward. Alliances in the book are fragile, often built on temporary needs rather than lasting loyalty.

Yet within the fractures, the possibility of female kinship remains an emotional anchor for characters like Alix and Hélène. Their understanding of each other’s struggles, even if unspoken, becomes a quiet form of resistance to the roles they are expected to play.

This theme serves to both critique the isolation women face and to celebrate the moments when they choose to lift one another out of it.

Class, Beauty, and Worth

Throughout A Queen’s Game, social hierarchy, physical appearance, and wealth function as brutal arbiters of a woman’s worth. May is constantly reminded of her inferior status—not just through her lack of wealth, but by the way society assesses her appearance and potential value in marriage markets.

She internalizes this hierarchy, viewing women like Alix and Missy with a mix of resentment and aspiration. Her repeated rejection by men of status, including George and Eddy, affirms a cruel social truth: that charm and intelligence mean little when weighed against beauty, pedigree, and dowries.

Agnes, the brash American heiress, enters the scene with money but without refinement, further disrupting these dynamics. Her boldness contrasts with May’s constrained decorum, and yet both are outsiders in their own way.

Hélène’s situation adds another layer—she holds a prestigious title, but one with no country, no power, and no wealth. Her beauty and defiance are not enough to shield her from disappointment or limit the expectations placed on her.

Alix, on the other hand, seemingly has it all—beauty, birth, and royal favor—yet even she suffers, trapped in gilded isolation and measured not by who she is, but by what she can offer as a future queen. The theme underscores how society assigns value to women through arbitrary and superficial measures, often at the cost of their emotional wellbeing and individuality.

It critiques the rigid and dehumanizing systems that reduce women to symbols of dynastic currency.