Across the Ages Summary, Characters and Themes

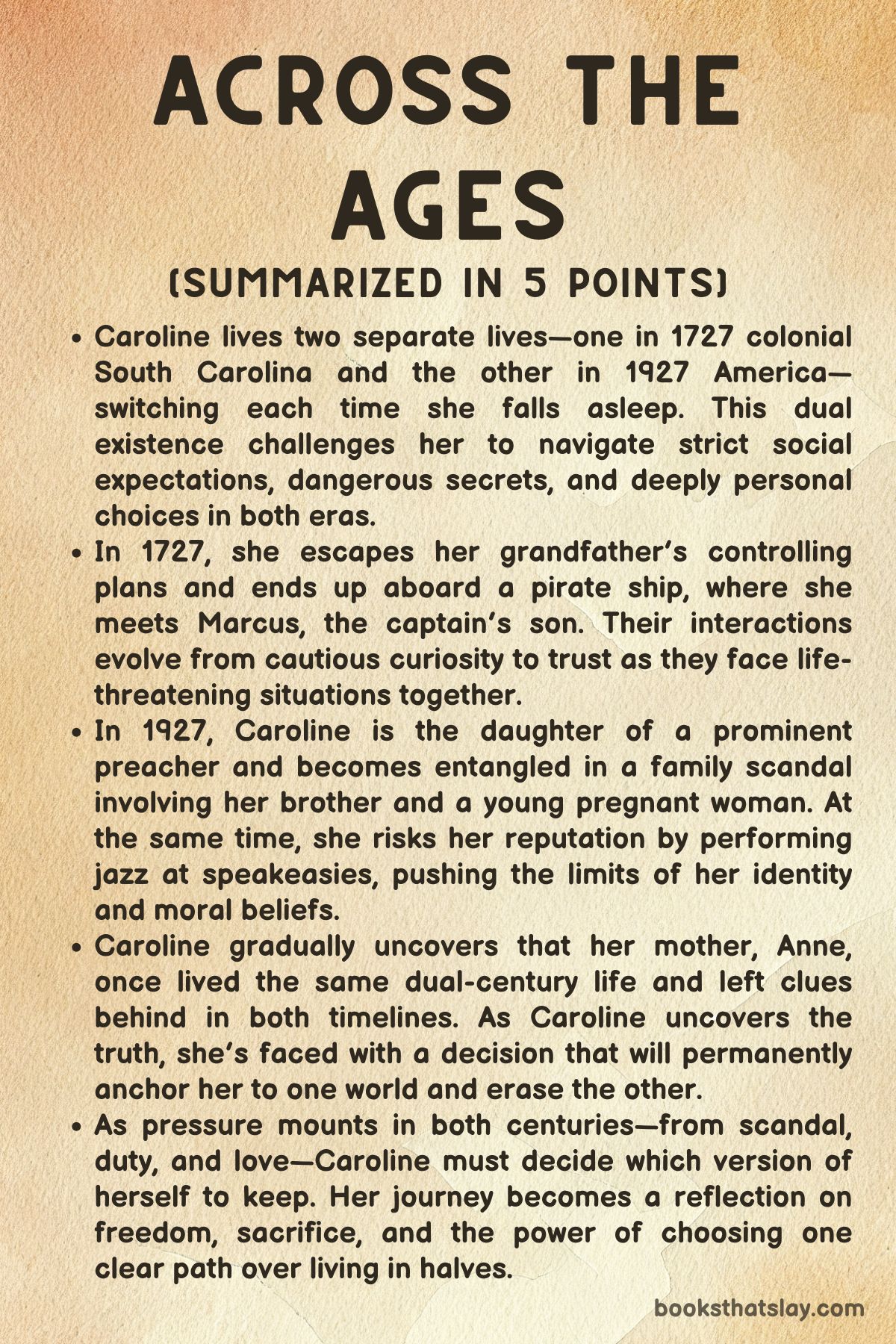

Across the Ages is the fourth book in Gabrielle Meyer’s Timeless series, and it offers a richly imagined dual-timeline narrative that explores one woman’s life split between two historical centuries. Caroline, the protagonist, navigates the conflicting expectations of 1727 colonial America and 1927 modern society.

Bound by a mysterious ancestral gift, she lives each day in a different era—caught between a Southern plantation’s rigid traditions and the free-spirited energy of Paris in the Roaring Twenties. The novel is a powerful meditation on identity, family, love, and the human yearning for freedom, all shaped by the choice that will define which of her two lives she will keep forever.

Summary

Caroline Baldwin Reed is not like most young women—each night, she falls asleep in one time and awakens in another. Her days are split between two drastically different centuries: the colonial world of 1727 and the modern age of 1927.

This duality defines not only her routine but also her emotional and psychological landscape, as she grapples with conflicting roles, expectations, and desires across time.

In 1727, Caroline lives as the granddaughter of plantation owner Josias Reed in South Carolina. Her existence is governed by the rules of wealth and inheritance, and Josias expects her to marry Elijah Shepherd to solidify a powerful alliance.

But Caroline is repelled by the idea of marrying someone she neither loves nor respects. Haunted by the mystery of her mother Anne’s disappearance and driven by a need to uncover the truth of her lineage, Caroline escapes the plantation disguised as a boy named Carl Baldwin.

She journeys to Charleston and then secures passage aboard a merchant ship, the Adventurer, hoping to reach Nassau where her mother may still be alive.

Her journey becomes even more perilous when the Adventurer is captured by pirates. Aboard the fearsome ship Ocean Curse, Caroline is forced into service under the command of Captain Edward Zale.

Among the crew is Marcus, the captain’s son and the ship’s quartermaster, who is intelligent, introspective, and unexpectedly kind. Though she lives in constant fear of being discovered, Marcus gradually begins to piece together her true identity.

Instead of betraying her, he pledges to protect her and even assist her in her quest to find her mother. A tender connection begins to form between them, enriched by shared conversations about literature, faith, and their respective pasts.

As her relationship with Marcus deepens, Caroline must also contend with the treacherous politics of the ship and the persistent danger of being unmasked.

Meanwhile, in 1927, Caroline lives in Minneapolis as the daughter of Daniel Baldwin, a nationally renowned preacher and staunch Prohibitionist. Her life here is materially comfortable but spiritually suffocating, as she is constantly scrutinized under her father’s public image.

Her cousin Irene, a rebellious flapper, introduces her to the electric nightlife of 1920s Paris, and Caroline experiences fleeting moments of self-expression and joy. At a Dingo Bar gathering, she mingles with figures like Ernest Hemingway and finds the confidence to perform on stage.

These experiences give her a glimpse of the life she longs for—free from judgment and the pressures of perfection.

Caroline’s modern timeline becomes increasingly complicated when Alice Pierce arrives at her home, claiming to be pregnant with her brother Andrew’s child. Though the family is skeptical and tries to handle the situation with discretion, Alice’s manipulative tendencies threaten to unravel the Baldwin family’s carefully constructed reputation.

Caroline is caught between loyalty to her sister-in-law Ruth and the need to maintain the family’s standing. At the same time, she reconnects with Lewis, a childhood friend turned police officer, who expresses his long-held romantic feelings for her.

Though she tries to process these emotions, her heart remains entangled with Marcus, the pirate from her other life.

On the Ocean Curse, Caroline’s life becomes more entangled when she is ordered to dive for sunken treasure from the Spanish fleet. Using a rudimentary diving bell, she descends to the ocean floor and manages to locate artifacts from the Capitana, but the dive nearly kills her.

She falls dangerously ill and is cared for by Marcus, who grows more protective and emotionally involved. Their relationship grows stronger, but the uncertainty of their futures looms over them.

Meanwhile, Caroline discovers that the ship’s young cabin boy, Ned, is actually a girl named Nadine. When Nadine suffers a miscarriage, Caroline helps her through the traumatic event in secret, once again risking her own safety for someone else’s.

Back in 1927, Caroline’s quest for identity leads her to new revelations about her mother, Annie Barker, who is now a criminal on the run. Lewis helps her track down Annie’s possible appearance at a local ballroom, and despite the danger, Caroline decides to go.

As her birthday nears, she knows the ultimate choice is coming: she can only remain in one timeline permanently after turning twenty-one. The stakes rise as she prepares to confront Annie while also coming to terms with the fact that whichever life she chooses, she must abandon the other—and everyone in it.

The emotional weight of this decision is mirrored in both timelines. In 1727, Marcus agrees to deliver Captain Zale to the authorities in exchange for a pardon, and Caroline insists on accompanying him to speak on his behalf.

The governor grants Marcus a pardon for his cooperation, offering him a new chance at life. Caroline and Marcus marry, and she visits Salem to meet Hope Abbott, an ancestor and fellow time-crosser.

From Hope, she learns that her mother Anne had faced the same decision and chose to remain in her own timeline, abandoning Caroline in order to protect her. Caroline is told that on her birthday, her body in the unchosen timeline will die.

In 1927, Caroline comes clean to her family. She reveals her dual existence and her love for Marcus.

Though stunned, her parents—especially her father—respond with compassion and acceptance. Daniel even draws upon his own checkered past to deliver a powerful sermon about redemption, inspired by his daughter’s courage and truth.

Caroline’s farewell to her family is heart-wrenching. She parts with Lewis, who respectfully accepts her choice, and shares a tender goodbye with Irene, whose own life has been changed by Caroline’s strength.

On her birthday, Caroline marries Marcus aboard a renamed ship called The Redemption. Together, they sail to Cape Cod, where Marcus is reunited with his long-lost parents in an emotional and healing reunion.

Caroline begins a new life as Caroline MacDougal, fully committed to her chosen world and the love she has found. Her journey, though marked by pain, danger, and sacrifice, ultimately leads her to a life of purpose, authenticity, and belonging.

Across the Ages concludes as a stirring affirmation of free will, love, and the courage it takes to forge one’s own destiny. Caroline’s decision is not without loss, but it is defined by the triumph of choice, the gift of second chances, and the timeless truth that identity is not imposed—it is claimed.

Characters

Caroline Reed

Caroline Reed is the heart of Across the Ages (Timeless #4) by Gabrielle Meyer, a deeply layered character whose dual existence defines the emotional and thematic arc of the novel. Living in two separate timelines—1727 South Carolina and 1927 Minneapolis/Paris—Caroline embodies the existential struggle between duty and desire, heritage and individuality.

In both lives, she is constrained by societal expectations: in 1727, she is expected to marry into Southern wealth for family legacy, while in 1927, she is burdened by the image of perfection her preacher father demands. Caroline’s unique ability to time-cross allows readers to witness her growth as she battles danger, love, fear, and personal awakening across centuries.

Her emotional core is shaped by the abandonment of her mother, Anne Reed (or Annie Barker), and her quest to uncover that history becomes a pursuit of identity itself. Disguising herself as a boy and boarding pirate ships, Caroline defies gender roles and confronts physical peril with bravery and conviction.

In the 1927 timeline, her courage is more emotional and moral—standing up to family scandals, resisting manipulative figures like Alice, and confronting the truth of her divided existence. Caroline is a complex synthesis of vulnerability and resilience, always questioning the life she’s supposed to lead and ultimately choosing the one she feels called to.

Her final decision to remain in 1727 with Marcus, and to accept the death of her 1927 body, showcases a radical act of love, belief, and self-ownership, cementing her as a protagonist of exceptional strength and spiritual clarity.

Marcus

Marcus, the pirate quartermaster aboard the Ocean Curse, emerges as one of the most compelling and morally intricate characters in the novel. Unlike his father, Captain Zale, who embodies ruthless piracy, Marcus is a figure of depth and conflict—loyal to his crew, yet guided by an internal compass that seeks redemption and goodness.

When he discovers Caroline’s true identity, his reaction is not one of betrayal or anger, but of compassion and silent admiration. His subtle kindness—offering Caroline books, privacy, and ultimately his protection—underscores a tender soul forged through years of rough living and ethical compromise.

Marcus’s development mirrors Caroline’s in many ways. Through their growing emotional bond, we see a man willing to evolve, to love selflessly, and to risk everything for another’s freedom.

Their intellectual and spiritual conversations elevate their connection beyond mere romance, delving into themes of guilt, faith, and personal worth. Marcus’s decision to turn himself and Captain Zale over to the authorities in Boston represents a climactic moral turning point, affirming his desire to shed a life of violence for one of peace and honor.

His eventual pardon and marriage to Caroline symbolize his spiritual rebirth and the power of grace—a theme that permeates the entire narrative. Marcus is not only Caroline’s love but her partner in transformation, proving that true redemption is possible even for those who have lived in shadow.

Daniel Baldwin

Reverend Daniel Baldwin, Caroline’s father in 1927, is a formidable yet sympathetic figure, representing the weight of moral authority and familial expectation. As a staunch Prohibitionist and spiritual leader, Daniel is deeply committed to public morality, often to the point of emotional rigidity.

His relationship with Caroline is strained by his demand for perfection and his inability to understand her inner turmoil—until her dual-life secret is revealed. Rather than reacting with outrage or disbelief, Daniel undergoes a powerful journey of acceptance that culminates in one of the novel’s most stirring moments: his confessional sermon.

Daniel’s backstory as a reformed ballplayer with a wild past adds crucial dimension to his character, showing that his righteous persona is born of personal failure and sincere repentance. This context makes his eventual embrace of Caroline’s truth more meaningful.

He does not merely forgive—he understands, drawing on his own narrative of transformation to accept hers. His faith, once a source of suffocating control, becomes a wellspring of grace and strength.

In blessing Caroline’s decision to remain in 1727, Daniel models a father’s highest calling: to love, let go, and believe in a destiny greater than one’s own expectations. His journey is one of spiritual maturity, making him a pivotal figure in Caroline’s life and in the moral architecture of the novel.

Lewis

Lewis, the childhood friend turned police officer in 1927, plays a quieter yet emotionally significant role in Caroline’s journey. As someone who has always harbored feelings for her, Lewis represents a path not taken—a life rooted in familiarity, protection, and conventional love.

His reappearance brings both comfort and complication. Caroline’s recognition that she cannot return his affection highlights the deepening of her own self-awareness and emotional clarity.

Lewis, however, handles this realization with a grace that reflects his inner strength and maturity.

Even after being turned down, Lewis continues to support Caroline in her quest to find her mother, even when that search leads into dangerous and emotional territory. His presence is steady, his love unselfish.

His eventual acceptance of Caroline’s decision, and his gentle shift of attention toward Irene, speaks to his resilience and generosity. Lewis is not just a character spurned—he is a symbol of quiet integrity and enduring friendship.

In a narrative filled with passionate and dramatic choices, Lewis serves as a touchstone of stability and goodness, helping to ground the emotional stakes of Caroline’s 1927 life.

Captain Edward Zale

Captain Zale, the fearsome pirate captain of the Ocean Curse, is an imposing presence and a foil to both Caroline and Marcus. His leadership is marked by cruelty, superstition, and manipulation.

Though he commands loyalty through fear, his character is also tinged with complexity—he is a man of the sea, hardened by survival, but lacking the moral compass his son begins to develop. His suspicion of Caroline, belief in curses, and brutal decisions reflect a worldview shaped by power and paranoia.

Zale’s refusal to change or seek redemption ultimately leads to his downfall. Marcus’s decision to turn him in, and the captain’s subsequent arrest, become acts of symbolic and literal liberation for both Caroline and his son.

Zale represents the weight of generational sin and unyielding pride, traits that both Marcus and Caroline must reject in order to find peace. As a narrative force, Zale is the dark storm that looms over the 1727 timeline, amplifying the stakes and serving as a catalyst for his son’s transformation and Caroline’s triumph.

Anne Reed / Annie Barker

Anne Reed, also known as Annie Barker in the 1927 timeline, is a mysterious and haunting figure whose absence shapes Caroline’s sense of self. Abandoning Caroline as a child and disappearing into a life of criminality, Anne exists at the fringes of both narratives until the latter half of the novel.

Her secret life as a time-crosser, like her daughter’s, reveals a legacy of pain, fear, and protection. Anne’s decision to leave Caroline was made in an effort to shield her from a dangerous man—an act of love disguised as desertion.

When Caroline finally learns more about Anne, the layers of misunderstanding begin to fall away. Her criminal past and recent sightings in 1927 Minneapolis suggest a woman shaped by desperation and complex motives.

The potential for a reunion adds urgency to Caroline’s emotional journey, offering the possibility of closure and reconciliation. Though Anne never takes center stage, her influence reverberates throughout the story, symbolizing both the pain of maternal absence and the redemptive power of truth.

Irene

Irene, Caroline’s cousin in 1927, embodies the carefree spirit of the Roaring Twenties. Her rebelliousness and embrace of jazz-age culture stand in stark contrast to Caroline’s restrained, duty-bound life.

Yet beneath her flamboyance lies a deep loyalty and affection for Caroline. Irene is not frivolous—she is bold, supportive, and willing to accompany Caroline even into risky and uncertain territory.

Her presence in Caroline’s life is a form of liberation. She reminds Caroline of the joy of spontaneity and the importance of choosing one’s own path.

Irene also becomes a symbol of new beginnings toward the end of the novel, with a possible romantic connection to Lewis. In this way, Irene continues the theme of redemption and forward motion that defines the novel’s conclusion.

She is the spark of rebellion that helps light Caroline’s path toward truth and freedom.

Themes

Identity and Self-Determination

Caroline’s existence across two centuries forces her into constant negotiation with identity. In both 1727 and 1927, she is not merely adapting to different time periods but resisting roles imposed by patriarchal and institutional structures.

In South Carolina, she’s bound by the expectations of being a plantation heiress, trapped in a strategic engagement to a man she does not love, and her only escape is to abandon femininity itself by disguising herself as a boy. Her very name, Carl Baldwin, is an act of rebellion and survival.

In 1927, though her social context is more modern, the constraints are no less suffocating. As a minister’s daughter, she is expected to embody moral perfection, silence her desires, and maintain appearances.

In both realities, her yearning for autonomy collides with familial and societal constraints. The revelation that her mother, Anne/Annie, also lived a dual life further complicates Caroline’s quest for identity.

It becomes evident that her struggle is inherited, not just chosen. Caroline’s final decision—to fully inhabit the 1727 life and renounce the other—represents a hard-won claim over her narrative.

She is not defined by her circumstances, lineage, or duty but by the life she chooses to own. Her identity is forged not by default but by courage and conscious choice.

The Burden and Blessing of Legacy

Family legacy in Across the Ages is not simply inheritance—it is a heavy tether that shapes every major decision Caroline must make. Her grandfather in 1727 sees her only as a means to secure generational wealth through marriage, disregarding her emotional well-being.

In 1927, her father’s religious reputation turns her life into a performance, where deviation risks disgrace. Caroline is constantly asked to carry the weight of family legacy, even as it endangers her happiness.

Yet legacy is not only a burden—it is also a source of insight and connection. The letter from her mother reveals a hidden family history of time-crossing, turning Caroline’s strange reality into a shared lineage.

When she meets Hope Abbott, another ancestor and time-crosser, the legacy becomes clearer—her ability to traverse centuries is a sacred gift passed down, accompanied by rules and consequences. These legacies are both tragic and redemptive.

Her father’s sermon about his own youthful sins and subsequent transformation speaks to a family pattern of overcoming shame through truth and grace. Caroline must bear the emotional weight of these inherited stories while also rewriting their endings.

Her final choice—marrying Marcus and embracing the name Caroline MacDougal—reframes legacy not as a trap but as an opportunity to shape the future with love and purpose.

Love as a Catalyst for Redemption

Love in this narrative is never shallow, never merely romantic—it is transformative. Caroline’s relationship with Marcus, born out of secrecy and forged in danger, gradually becomes a sanctuary where she is fully seen.

Their conversations about guilt, faith, and literature bring depth to their connection, and Marcus’s willingness to risk everything for her reflects a profound shift in his character. He evolves from pirate to protector, not through Caroline’s influence alone, but through the love that reveals to him a path beyond violence and plunder.

Caroline’s love for Marcus compels her to return to Charleston, testify before the governor, and stand by him in a moment of life-altering consequence. Their union is a mutual redemption—she escapes a legacy of constraint, and he escapes a life of crime.

Parallel to this is the redemptive arc of Daniel Baldwin, whose love for his daughter transcends dogma and reputation. His decision to accept Caroline’s truth and share his own sins in a public sermon becomes an act of familial redemption.

Love is not safe or easy in this book, but it is powerful—it heals, liberates, and redeems both the individual and the community.

The Price and Power of Choice

Every meaningful moment in Across the Ages hinges on choice. Caroline’s dual life is governed by a ticking clock—on her twenty-first birthday, she must choose one life and lose the other.

That looming decision underscores every action she takes, adding weight and urgency to her experiences. Her early choices—escaping her grandfather’s estate, dressing as a boy, sneaking onto a pirate ship—are acts of defiance driven by necessity.

But as her character matures, her choices evolve into expressions of agency. She chooses to return to Charleston despite personal risk, chooses to marry Marcus even knowing the cost, and chooses to bid farewell to her family in 1927 with grace rather than regret.

These decisions are not easy; they demand sacrifice. Choosing one life means letting another die—literally.

Yet through these painful choices, Caroline transforms from a girl reacting to the world around her into a woman shaping her destiny. The book insists that freedom is not about escaping consequences but embracing responsibility.

The final moments—her marriage, her new name, her departure on The Redemption—are not simply happy endings; they are affirmations of choice as the most powerful tool we have to determine who we become.

Faith and Forgiveness

Faith in Across the Ages is not dogmatic—it is deeply personal, intimately tied to characters’ abilities to forgive themselves and others. Caroline grows up under the spiritual rigidity of her father’s pulpit, but it is not until he admits his own sins that his faith becomes real to her.

His sermon, grounded in transparency, gives the community permission to forgive and be forgiven. This theme is echoed in Marcus’s journey.

Haunted by a life of piracy and burdened by his loyalty to a violent father, Marcus finds in Caroline not only love but a path to spiritual peace. His choice to turn in Captain Zale and seek pardon is not just a legal act—it is a moral reckoning.

Caroline herself struggles with forgiveness, particularly in reconciling the mother who abandoned her with the woman she’s come to understand through fragments of truth. The final image of The Redemption sailing toward Marcus’s family is a fitting culmination of these threads.

Forgiveness in the novel is never presented as easy—it is a process that demands honesty, courage, and the willingness to be vulnerable. Yet through it, characters find grace, connection, and renewal.

The novel makes clear that faith is not merely belief in divine power but belief in the power of second chances.