Brightly Shining Summary, Characters and Themes

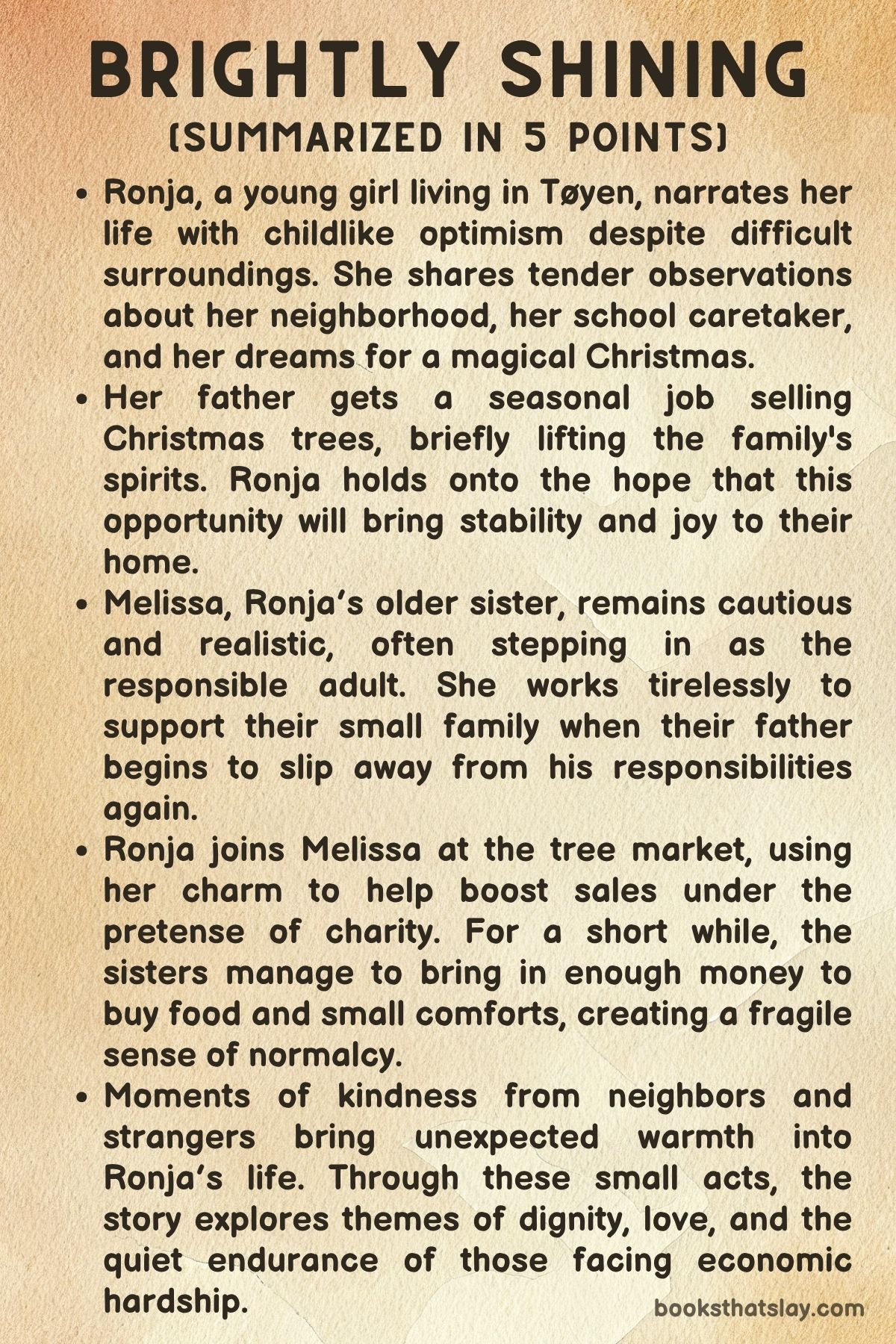

Brightly Shining by Ingvild Rishøi is a profoundly tender and poetic portrait of childhood, poverty, and endurance in the cold edges of a Norwegian winter. At the heart of the novel is Ronja, a young girl whose quiet resilience and vivid imagination illuminate the harsh circumstances of her life.

Through the fractured lens of her family—particularly a loving yet unreliable father and a fiercely protective sister—Ronja’s story captures the emotional currents of hope, longing, and disappointment that ripple through their everyday struggles. More than just a seasonal tale, Brightly Shining explores the quiet heroism of children forced to carry the emotional burdens of adults, showing how warmth, dreams, and small kindnesses can survive amid the bleakest conditions.

Summary

Ronja is a young girl who lives in poverty with her father and older sister, Melissa. Their life is shaped by scarcity, uncertainty, and the long shadow of their father’s alcoholism.

Despite this, Ronja seeks connection and comfort in small, everyday moments. She finds quiet companionship in the school caretaker, who offers her food and eventually shares a job flyer for a seasonal Christmas tree market.

Ronja brings the flyer home, imagining that this opportunity might be the miracle her father needs to reclaim his purpose and bring some joy into their lives.

At first, her father dismisses the idea. But gradually, a fragile spark of hope is kindled.

He begins to show interest, preparing to take on the job with a sense of renewed energy. For a short while, life improves.

He stocks the fridge, talks enthusiastically about tree deliveries, and includes Ronja in his thoughts and plans. Ronja allows herself to believe in a version of him that is present, reliable, and admired.

But Melissa, the older sibling who has long since lost faith in their father’s promises, remains cautious. Her wariness proves justified when their father vanishes again, succumbing to his old habits.

Melissa quietly steps into his role at the Christmas tree market, taking on responsibilities far beyond her years. She works long hours in the bitter cold, facing physical exhaustion and the emotional strain of pretending everything is fine.

She doesn’t complain, instead doing what’s needed to keep them afloat. Meanwhile, Ronja is recruited by Tommy, another employee, to help sell wreaths as part of a fundraising scheme.

Though the initiative is morally ambiguous—using her image and story to market to sympathetic customers—it becomes a source of empowerment for Ronja. She earns money, experiences the pride of productivity, and momentarily feels seen and valued.

This period is one of quiet transformation. Ronja grows in confidence and learns the rituals of work and social interaction.

Yet the underlying fragility of her world becomes evident when Eriksen, the market’s owner, discovers she is underage and fires her. The dismissal shatters Ronja’s brief moment of triumph, thrusting her back into the bleakness of home life.

School becomes a place of shame, and her father remains absent. Melissa, despite her protective instincts, is stretched thin.

Ronja begins to understand just how precarious their existence is.

Amid these hardships, the Santa Lucia celebration becomes a symbol of hope and disappointment. Ronja dresses up for the event, hoping her father will come.

When he doesn’t, her grief is quiet but deep. However, a chain of kind adults begins to fill the gaps he leaves behind.

The caretaker provides gentle encouragement. Aronsen, an older neighbor, steps in with unexpected warmth—helping Ronja prepare for the celebration, feeding her, and showing her a form of care that feels like love.

As Christmas approaches, Ronja makes a tentative return to the market. Melissa continues to work while trying to shield her sister from Eriksen’s anger.

When Eriksen returns, threatening them with police involvement and wage withholding, the tension escalates. Ronja hides beneath a tree, watching as Melissa and Tommy are berated.

From her hiding place, Ronja is overcome by fear and memories—of child services, of her father’s grim views, of abandonment. Her mind spins with guilt and helplessness, and she falls asleep under the branches, escaping into memories of happier times.

Melissa’s panic when she discovers Ronja missing is visceral. She shakes her sister awake, overwhelmed by fear, guilt, and exhaustion.

Tommy tries to mediate, urging Ronja to stay away to avoid trouble. The emotional toll on all three is heavy, and it becomes clear that they are bound together not just by circumstance but by a desperate need for one another.

In the midst of all this, Ronja begins to see meaning in the chaos—interpreting memories and gestures as signs of hope.

Taking the lead, Ronja guides Melissa to a dry space under the spruce, creating a sanctuary amid the storm. She becomes the comforter now, telling stories of cabins in the woods and stoves glowing with warmth.

This act of kindness, of imagination, is transformative. Melissa, for once, is allowed to rest.

Ronja’s love and belief in magic create a moment of peace, of sisterhood unburdened by fear or responsibility.

By morning, the storm has passed. Light filters through the branches, and the girls emerge into a world momentarily washed clean.

They walk together through the snow, hand in hand. The woods become symbolic of escape, safety, and rebirth.

Though their problems remain unsolved, this walk into the forest is a step toward healing—a moment of shared hope.

The story ends on a note of quiet resilience. Ronja reflects on those who have offered her comfort—Tommy, the caretaker, Aronsen—and dreams of her father, still believing in his love despite everything.

The gift of a Christmas tree, delivered by Alfred, a stranger connected to Tommy, becomes a final gesture of grace. Though her world is uncertain, Ronja holds fast to the belief that love can endure, that miracles are still possible, and that storytelling itself can be a form of survival.

Brightly Shining does not offer easy answers or fairy tale resolutions. It is instead a meditation on how children survive instability and loss by imagining something better, and how even in the harshest winters, the warmth of human connection can keep hope alive.

Characters

Ronja

Ronja is the emotional and narrative core of Brightly Shining, a young girl navigating the stark realities of poverty, neglect, and emotional abandonment with a fragile but tenacious hope. Her character is rendered through a deeply introspective lens, capturing both her innocence and the slow erosion of that innocence as she becomes increasingly aware of her world’s instability.

From the outset, Ronja reveals a capacity for connection and empathy, particularly in her friendship with the school caretaker, whose small acts of kindness she treasures. Her discovery of the Christmas tree job becomes a vessel for hope—a child’s dream that a single good deed or opportunity might mend a fractured world.

Ronja’s fantasies of her father succeeding and their family finding stability reflect a desperate longing for magic and permanence, emotional motifs that resurface in her repeated dreams of a snow-covered cabin deep in the woods.

Even as reality crushes these dreams—when her job is taken away, when her father relapses, and when Melissa must pick up the broken pieces—Ronja’s ability to imagine, to endure, and to find symbolic meaning remains unshaken. Her temporary joy at being part of the wreath-selling campaign and her childlike pride in earning money is bittersweet, highlighting the fine line between exploitation and empowerment.

But perhaps Ronja’s most powerful transformation comes in the final act, when she comforts Melissa beneath the tree branches. No longer just the dreamer, she becomes the nurturer, embodying love, resilience, and grace.

Ronja ultimately emerges as a beacon of endurance—a child who survives through the power of imagination, emotional intelligence, and unyielding love for those around her.

Melissa

Melissa is the quiet backbone of the story—a character whose strength is forged in hardship and whose love is expressed through sacrifice rather than sentiment. As Ronja’s older sister, Melissa has clearly taken on a parental role, acting as both protector and provider in the absence of a dependable adult.

Her realism stands in direct contrast to Ronja’s hopeful dreaming; she knows their father too well, has seen too many broken promises, and recognizes the emotional and physical toll of relying on him. While Ronja sees the Christmas tree job as a chance for redemption, Melissa braces herself for disappointment, understanding that hope can be dangerous when built on a shaky foundation.

When their father disappears, Melissa does not flinch. She takes on his job at the market with a kind of resigned bravery, enduring cold, fatigue, and indignity without complaint.

Her interactions with others—particularly Tommy—are guarded but laced with subtle warmth, suggesting a complexity beneath her hardened exterior. Melissa’s fierce loyalty to Ronja is perhaps her defining trait.

She is the one who shields her sister from Eriksen, the one who works until she breaks, and the one who ultimately falls apart not from her own suffering, but from fear for Ronja’s safety. The moment when Melissa is comforted by Ronja beneath the spruce tree is a poignant inversion of roles—proof that her vulnerability, long buried, can still be held with tenderness.

Melissa is a portrait of exhausted resilience—a girl who grows up too fast, carries too much, and still finds the strength to keep her family together.

The Father

Ronja and Melissa’s father is a complex and deeply flawed figure, a man whose charm and tenderness flicker intermittently through a haze of addiction and instability. His character is drawn with compassion and frustration in equal measure.

He is whimsical and charismatic, able to inspire affection and even admiration when he is sober and focused. Ronja’s visions of him bringing a Christmas tree to her school, smiling and participating in life, speak to his underlying potential and the remnants of the father he might have been.

However, these flashes of warmth are fleeting, often undone by his chronic unreliability and alcoholism. His vanishing acts, broken promises, and general absence make him a source of both hope and heartbreak for his daughters.

Yet he is not portrayed as a villain. His failings are contextualized within a cycle of poverty and emotional damage that predates the narrative.

When he does engage, he seems genuinely invested—talking animatedly about trees, showing moments of pride, and even sharing meals with his daughters. But ultimately, his inability to provide consistent care undermines his moments of connection.

His absence during the Santa Lucia celebration and the eventual collapse of his brief employment reinforce the recurring theme that his love, though real, is not enough to protect his children from harm. Despite this, Ronja continues to dream of his return, a testament to the deeply ingrained bond between parent and child.

He is a tragic character—one who symbolizes both the emotional toll of systemic failure and the enduring, if fragile, ties of family.

Tommy

Tommy serves as a transitional figure between childhood and adulthood, representing both risk and solidarity for Ronja and Melissa. Slightly older and more worldly, Tommy introduces Ronja to the wreath-selling campaign and offers Melissa companionship in the grueling world of seasonal labor.

While his recruitment of Ronja into the campaign might appear exploitative on the surface, his motivations are more layered. He recognizes Ronja’s need for purpose and gives her an opportunity to feel seen and valuable, even if the ethical boundaries are blurred.

His presence at the market is marked by a certain charisma and resourcefulness, suggesting he too is a survivor, navigating poverty with limited tools.

Tommy also exhibits genuine care, especially in his concern for Ronja’s safety when Eriksen threatens to involve authorities. His fear and helplessness in that moment mirror Melissa’s, showing that, despite his bravado, he too is just a kid trying to hold together a fragile world.

In the climactic moments beneath the spruce tree, Tommy functions as an emotional touchstone—someone who shares in the burden without offering false promises. His support, while imperfect, is sincere.

Tommy embodies the reality of adolescence under pressure: he is resourceful, flawed, loyal, and deeply aware of the precarity around him. His character reflects the painful balancing act of trying to do good within a broken system.

Eriksen

Eriksen is the embodiment of institutional cruelty and unchecked power in Brightly Shining. As the owner of the Christmas tree market, he initially appears as a gruff but manageable figure, willing to bend the rules if it serves his interests.

However, as the story progresses, he becomes a looming threat to Ronja, Melissa, and Tommy, wielding authority with little regard for their vulnerability. His discovery of Ronja’s underage employment becomes a turning point, and instead of showing understanding, he uses the opportunity to assert dominance—firing her, threatening child services, and holding the threat of withheld pay over Melissa and Tommy’s heads.

Eriksen’s behavior is marked by manipulation and intimidation, making him one of the story’s most antagonistic forces. He does not see the children as individuals, but as expendable laborers whose value is tied to compliance and profit.

His threats destabilize the precarious equilibrium that Ronja and Melissa cling to, and his disregard for their fear underscores the broader theme of systemic neglect. Yet, Eriksen is not portrayed with theatrical villainy; rather, his cruelty is bureaucratic, cold, and realistic—a reflection of how institutions often fail the most vulnerable by dehumanizing them.

His character highlights the moral vacuum that surrounds child poverty and labor, turning real human lives into liabilities and paperwork.

Aronsen

Aronsen is a quiet but pivotal figure in Ronja’s emotional journey, representing an unexpected source of kindness and dignity. As an elderly neighbor, he initially seems peripheral, but his actions gradually reveal a deep empathy and willingness to step into a caregiving role when no one else will.

His decision to iron Ronja’s costume, feed her breakfast, and attend her performance is profoundly moving, offering her a rare moment of being cared for without condition or expectation. Aronsen functions almost like a surrogate grandfather, a symbol of intergenerational solidarity and gentle humanity in a world that is otherwise indifferent.

What makes Aronsen’s presence so powerful is its subtlety. He does not speak much, nor does he impose himself, but his gestures resonate because they are freely given.

In a story dominated by absence—of parents, of stability, of institutional support—Aronsen becomes a steady, if fleeting, anchor. His care reinforces the idea that even in the darkest circumstances, unexpected connections can offer warmth and affirmation.

For Ronja, his presence is not just comforting; it is transformative, reminding her that love can come from the unlikeliest of places.

The Caretaker

The school caretaker is another quiet hero in Brightly Shining, a figure whose minor acts of kindness ripple throughout the narrative in profound ways. His friendship with Ronja, characterized by shared snacks and unobtrusive support, introduces the central theme of connection through small gestures.

It is he who first offers Ronja the flyer about the Christmas tree job, unknowingly setting in motion the story’s central events. More importantly, he remains a steady, nonjudgmental presence, offering Ronja validation in a world where adult authority figures are often indifferent or punitive.

His support during the Santa Lucia celebration is particularly poignant. As Ronja stands vulnerable, waiting for her absent father, the caretaker’s presence offers a buffer against heartbreak.

He doesn’t offer grand solutions or emotional speeches; instead, he simply stands beside her, reinforcing her dignity through quiet solidarity. This kind of low-stakes emotional anchoring is a recurring motif in the story—proof that love and care do not always come with declarations or promises, but can be just as meaningful in silence.

The caretaker’s role underscores the narrative’s belief in the cumulative power of small kindnesses in a child’s life.

Alfred

Alfred enters the story as a mysterious yet profoundly symbolic figure—someone tied to Tommy but set apart by his quiet grace and generosity. His arrival near the end, bearing the beautiful fir tree promised by Ronja’s father, transforms him into a near-mythical figure of fulfillment and closure.

In a story haunted by broken promises, Alfred delivers. He offers Ronja not just the physical tree, but emotional validation—proof that she is seen, remembered, and worthy of joy.

Though little is known about Alfred’s background or motivations, his presence is suffused with warmth and quiet reverence. He operates outside the transactional world of Eriksen and the Christmas market, offering a gesture that is both intimate and redemptive.

For Ronja, Alfred’s gift becomes a bridge between memory and reality, between fantasy and healing. His role may be small in terms of page time, but its emotional weight is immense, serving as the final act of kindness that affirms Ronja’s sense of self and brings the narrative to a gentle, hopeful close.

Themes

Poverty and Its Emotional Landscape

In Brightly Shining, poverty is not merely a backdrop but an active, destabilizing force that governs the lives of Ronja, her sister Melissa, and their father. It seeps into every corner of their daily experience, shaping their sense of identity, worth, and possibility.

The narrative captures poverty as cyclical, inescapable, and deeply personal. It isn’t dramatized with extravagant hardship, but rather made painfully real through small, recognizable indignities: an empty fridge, the constant fear of eviction, and the emotional whiplash of a father’s unreliable presence.

Ronja’s father, a man rendered both fragile and endearing by his failures, serves as a symbol of how poverty can erode responsibility and spirit. His fleeting attempts at redemption—fueled by a temporary job—ignite Ronja’s imagination but are viewed with wary eyes by Melissa, who has learned not to trust the brief sparkle of his hope.

Melissa’s decision to take over their father’s job when he inevitably fails reflects how poverty demands adult sacrifices from children. She is forced to carry burdens that should never be hers, standing for hours in the cold and performing labor masked as festive cheer.

The contrast between Ronja’s innocent excitement over earning a few coins and Melissa’s crushing fatigue at the Christmas tree stand encapsulates how poverty differentially shapes childhood and adolescence. Even when the job allows for momentary dignity and a semblance of normalcy, these instances are fragile.

The presence of figures like Eriksen, with his power to terminate employment and threaten legal consequences, highlights how those who control economic lifelines can wield them with cruelty, reminding the girls that even their moments of reprieve are precarious. The result is a childhood colored by fear, resourcefulness, and emotional resilience—a vivid portrayal of the emotional terrain poverty demands its inhabitants to survive.

The Fragility and Resilience of Family Bonds

The relationship between Ronja, Melissa, and their father forms the emotional center of Brightly Shining, illustrating how familial love persists in spite of broken promises, neglect, and deep emotional wounds. Their father is a man who occasionally offers joy and inspiration, but more often disappears into the fog of alcoholism and irresponsibility.

Yet Ronja’s love for him remains intact, unshaken even by his repeated absences. Her dreams of him delivering a Christmas tree, or showing up at her school celebration, are manifestations of her emotional resilience—evidence that love does not vanish in the face of disappointment, but often adapts, hoping for eventual redemption.

Melissa’s bond with Ronja is more immediate and sacrificial. Where their father fails, she steps in without complaint.

She feeds, clothes, and protects Ronja, working in punishing conditions and absorbing the emotional blowback of their father’s instability. Her love is expressed not through grand gestures but through small, continuous acts of care—shivering through early mornings, enduring Eriksen’s threats, and ultimately panicking when Ronja goes missing.

Even her angry outbursts are layered with fear, guilt, and helplessness, showing that her stern demeanor is not cruelty but a shield against the chaos.

These family ties are marked by an imbalance—Ronja gives her love freely, Melissa gives her labor and protection, and the father gives moments of light that never last. And yet, the bond holds.

It is not idealized; it is tested, bent, sometimes frayed. But it never truly breaks.

In the story’s final moments, when Ronja comforts Melissa under the spruce tree, the roles reverse. The younger child becomes the caretaker, showing how love in this family isn’t static but fluid, moving where it is most needed.

The fragility of their relationships, constantly under siege by poverty and trauma, is matched only by their quiet, stubborn durability.

The Psychological Cost of Neglect and Adult Failure

Through Ronja’s internal landscape, Brightly Shining reveals how children absorb and interpret the failures of adults around them. Her observations are often quiet but emotionally acute, shaped by a constant need to make sense of a world that is both beautiful and hostile.

The recurring image of the fjord spruce tree, for instance, becomes not just a physical refuge but a psychological one. It is under this tree that Ronja hides, sleeps, dreams, and later offers comfort to Melissa.

The tree becomes a symbol of her mind’s ability to carve out sanctuary in an otherwise volatile environment.

Ronja’s emotional development is marked by episodes of disillusionment, such as being fired for being underage, or her father’s absence from the Santa Lucia celebration. These moments are not just disappointments; they are formative.

They teach her about powerlessness, about how even joy is conditional and easily taken away. Her hallucinations during illness—her fear of child services, her guilt, her longing—are a child’s attempt to reckon with abandonment and shame.

Her worldview is shaped not through lectures or discipline, but through a piecing together of small clues: her father’s bitterness, Melissa’s tears, Eriksen’s threats.

And yet, Ronja’s imagination becomes her saving grace. She envisions a better life, not one of luxury, but one of warmth, safety, and togetherness.

These are not idle fantasies but coping mechanisms, emotionally sophisticated methods of survival. In comforting Melissa with stories of the woods and a warm cabin, Ronja reclaims some control over her narrative.

She demonstrates that even in the face of systemic neglect and fractured family dynamics, a child’s inner world can offer resistance—not in loud rebellion, but in sustained belief and quiet care. The cost of growing up in such circumstances is immense, but Ronja’s emotional response reveals a depth of strength often overlooked in narratives about childhood.

Hope as a Survival Mechanism

Throughout Brightly Shining, hope operates less as a fixed goal and more as a state of endurance. Ronja doesn’t hope for wealth or success, but for a father who smiles, a kitchen with food, or a sister who is not burdened.

Her dreams of the snow-covered cabin in the woods are modest but radiant, filled with soft beds, warm stoves, and family. These images recur not because they are realistic, but because they sustain her.

They give her something to hold onto when school humiliates her, when the Christmas market closes its doors, or when her body is wracked with fever and fear.

Hope, in this story, is not naive. It is not the denial of suffering, but a response to it.

Melissa sees through the illusions their father spins, but she does not mock Ronja’s fantasies. She even listens to them, allows them to soothe her when reality becomes too cruel.

That shared moment under the spruce tree is emblematic of the kind of hope this book portrays—tender, temporary, and deeply human. It allows them to rest, to regroup, to remember that kindness is still possible even in the coldest places.

Hope, in Ronja’s hands, becomes an instrument of agency. She decides to reframe her environment, to construct a narrative where she is no longer the helpless observer but the guiding force.

She becomes a giver of warmth, a storyteller, a caretaker. Her belief in something better—however fleeting—is not just emotional comfort but a form of resistance.

It allows her to remain soft in a world that tries to harden her. It helps her love people who fail her.

And it offers her, and the reader, the quiet truth that even a fragile belief can sometimes be enough to get through another day.