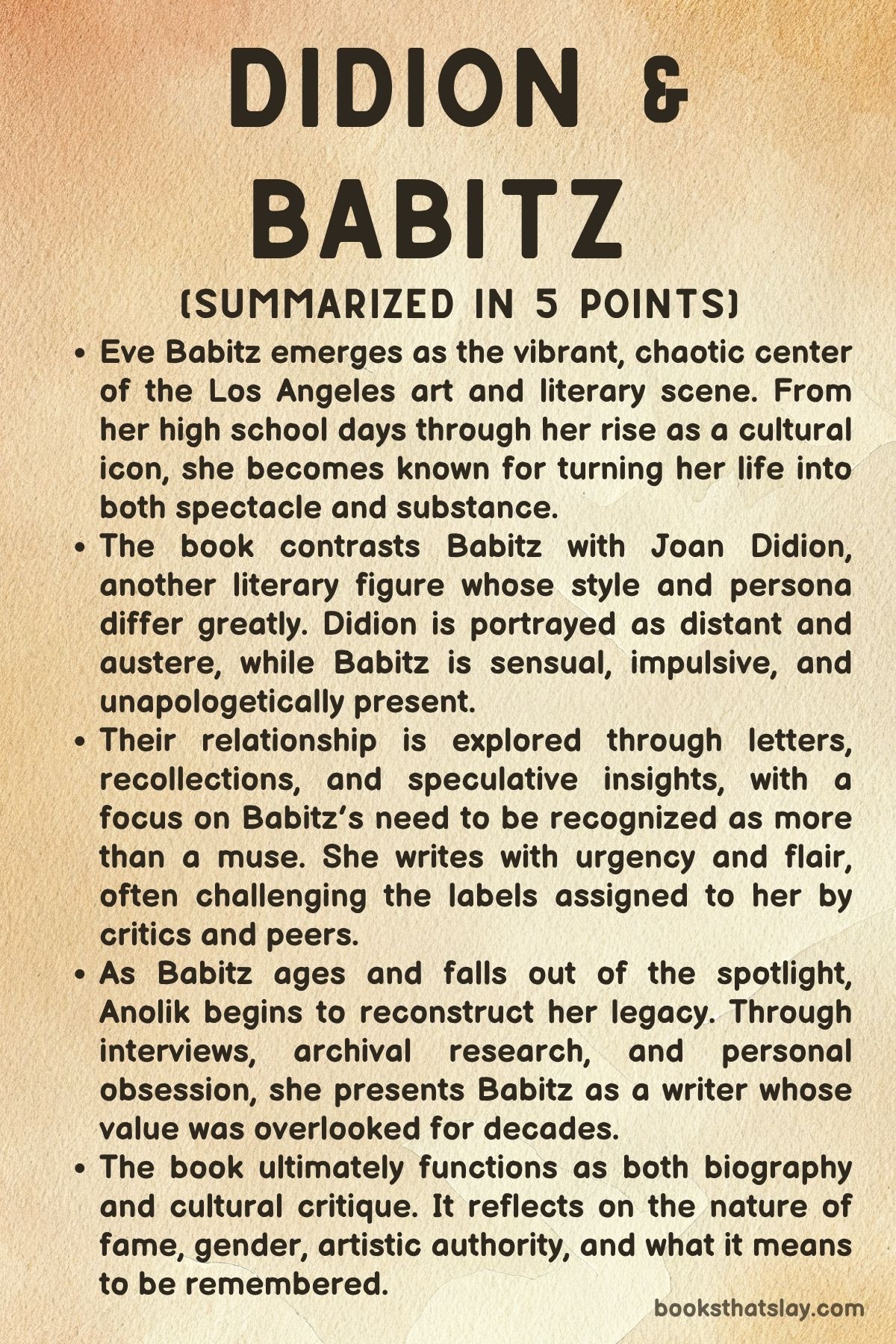

Didion and Babitz Summary and Analysis

Didion and Babitz by Lili Anolik is a sharp, deeply evocative double portrait of two contrasting women who helped define the literary and cultural fabric of Los Angeles in the latter half of the 20th century.

Through the lens of Eve Babitz’s chaotic charisma and Joan Didion’s cool detachment, Anolik reconstructs not just individual trajectories, but a broader narrative about womanhood, ambition, and authorship in a male-dominated landscape. The book is more than biography—it’s part investigative memoir, part cultural history, and part critical exhumation. It asks what it means to be remembered, and what kind of woman gets to be canonized. Anolik gives Babitz her long overdue recognition while using Didion as both foil and frame.

Summary

Didion and Babitz tells the story of Eve Babitz, a woman at once inseparable from and estranged within the glamorous cultural sprawl of Los Angeles. Raised in a home that resembled a bohemian salon—complete with guests like Stravinsky and O’Keeffe—Eve was steeped in high art from birth.

Yet she found herself more enthralled by the gloss of Hollywood and the rebellious energy of pop culture. Her awakening didn’t come from childhood memories but from a moment of self-realization in a high school bathroom, where smoking with a peer named Holly became a rite of passage.

Holly’s trajectory—a cautionary fall into addiction and obscurity—offered Eve a living warning of what could happen if she gave in completely to the era’s seductive ruin.

Eve’s early years unfolded in a home that straddled both highbrow prestige and lowbrow indulgence. Her parents and godfather rooted her in artistic refinement, but Eve chose rebellion.

She rejected the idealized postwar femininity embodied by her high school peers and found community in the subversive contemporary art scene at Barney’s Beanery. There, she connected with Walter Hopps, an influential curator who became her lover and mentor.

Their affair turned sour when Hopps excluded her from a significant event he organized for Marcel Duchamp, opting instead to honor his wife. Eve’s retaliation was both literal and symbolic—posing nude, playing chess with Duchamp for a now-iconic photo that both immortalized her and reclaimed her autonomy.

Writing soon became another outlet for Eve’s self-expression. After a brief stint in Europe, where she was devastated by Marilyn Monroe’s death and tangled in a doomed romance with Brian Hutton, Eve returned to Los Angeles and began composing bawdy, epistolary letters that would eventually morph into her first literary experiments.

Though her writing lacked maturity and tonal complexity, it marked the emergence of the performative, sensual voice that would come to define her work. Her public persona was brazen and witty, but her private journals revealed a woman uncertain, wounded, and desperate to be taken seriously.

Men, especially powerful literary figures, played outsized roles in both enabling and constraining her creative journey. Her letters to Joseph Heller blended seduction and self-promotion, revealing her acute awareness of how femininity and access were often inseparable.

While she occasionally secured their admiration and help, true validation proved elusive. Editors dismissed her early work for lacking depth, and her emotional fragility often left her unable to navigate rejection.

Her heartbreaks, whether personal or professional, were profound yet masked by a veneer of cool indifference.

Her attempts at emotional transparency were often sabotaged by her own insistence on maintaining a comic, distant tone. Her relationship with Hutton, marked by erotic intensity and eventual heartbreak, was barely acknowledged in her fiction, and her devastation over Marilyn Monroe’s overdose was concealed behind sardonic prose.

As much as she longed to be seen as a serious writer, she also feared vulnerability. The result was a body of early work that sparkled with wit but lacked emotional gravity.

Her physical beauty and sexual boldness made her a muse, but she refused to stay in that lane. Her visual art—album covers and photography collaborations—demonstrated her belief that femininity and artistry need not be at odds.

She tried her luck in New York, chasing struggle as a route to legitimacy, but the city proved cold and hostile. She was sexually harassed, creatively stifled, and culturally alienated.

Still, she found inspiration in artists like Joseph Cornell, whose collage work affirmed her desire to blend the personal and visual in innovative ways.

Back in Los Angeles, her persistence paid off. A short story titled “The Sheik” was published by Rolling Stone, marking her literary debut on her own terms.

No seduction, no games—just raw talent. But this success created ruptures in her personal life.

Her boyfriend, Dan Wakefield, who had just been rejected by the same magazine, dumped her in a fit of ego and jealousy. Her subsequent relationship with editor Grover Lewis was equally destructive, ending with her being kicked out of their shared apartment with her belongings in pillowcases.

Despite this, Eve kept going, drawing support from cultural titans like Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne.

Didion, in particular, played a dual role: mentor and threat. She helped Eve secure a book deal and quietly edited her first book, Eve’s Hollywood.

But the mentorship turned sour. Eve came to resent Didion’s control, viewing her cool editorial touch as suffocating to her raw, impulsive style.

Their relationship devolved into rivalry, and Eve eventually severed ties, portraying Didion in her fiction as cold and alienating. With the publication of Eve’s Hollywood, Babitz made her mark, even if commercial and critical success were muted.

Her voice—loose, funny, carnal—stood in direct opposition to Didion’s precise, detached prose.

The following years saw Eve reckoning with addiction, artistic burnout, and emotional disillusionment. At age thirty-nine, she joined Alcoholics Anonymous, an act that estranged her from Joan and the permissive Hollywood scene that had once embraced her.

A tragic incident—the murder of Dominique Dunne—symbolized for Eve the death of an era, forcing her to confront the dark underbelly of the cultural romanticism she had once thrived in.

Sobriety, however, came at a cost. Creativity dulled, and for years she drifted, until the publication of her essay collection Black Swans marked a tentative return.

The collection was more subdued, haunted by age, regret, and the creeping presence of Didion’s dominance in the literary world. Then came tragedy: a freak accident in 1997 left Eve with life-threatening burns.

Her recovery was long and painful, but it revealed the loyalty she had earned. Friends and fans rallied to her side, offering financial and emotional support.

As Eve aged, she receded from public life. But fate had a final twist in store.

Journalist Lili Anolik rediscovered her, publishing a piece in Vanity Fair that sparked a revival of interest in her work. Suddenly, her books were being reissued, and younger audiences saw her not as a footnote to Didion, but as a cultural icon in her own right.

Still, the renewed attention came too late. Living in obscurity and increasingly frail, Eve watched from the sidelines as her legacy was finally cemented.

The story ends with a quiet but poignant symmetry. Both Eve Babitz and Joan Didion died in December 2021, six days apart.

Didion exited the world with formal accolades and institutional reverence. Eve died in the shadows, but with a newly reclaimed place in the literary imagination.

Together, their lives form a kind of dual portrait of American womanhood—one cerebral and restrained, the other chaotic and embodied. Didion and Babitz suggests that both were essential, and that in their differences, a fuller story of artistic ambition, cultural rebellion, and female self-determination can finally be told.

Key People

Eve Babitz

Eve Babitz is the magnetic core of Didion and Babitz, a figure both seductively mythic and painfully human. Her early life is marked by a rare blend of highbrow cultural immersion and a deep infatuation with Hollywood’s lowbrow spectacle.

Born into a privileged circle that included her composer godfather Igor Stravinsky and frequented by luminaries like O’Keeffe and Chaplin, Eve’s childhood was imbued with art and intellect. Yet, this cultivated upbringing never eclipsed her passion for pop culture, sensuality, and performative chaos.

Her defining moment of self-awareness happens not in the drawing rooms of the avant-garde but in the bathroom of Hollywood High, revealing how her identity is shaped by defiance rather than inheritance. Throughout her journey, she embodies contradictions: artist and muse, object and author, participant and observer.

Her legendary photograph with Duchamp represents the precise alchemy of sexuality and intellect she weaponizes to both rebel and belong.

Eve’s romantic entanglements, particularly with married men like Walter Hopps and Brian Hutton, parallel her complex relationship with artistic legitimacy. These men serve both as patrons and betrayers, drawing out her talent even as they undermine her self-worth.

Writing becomes Eve’s act of reclamation, yet her early works are emotionally flattened—witty but emotionally stunted, revealing her difficulty in balancing vulnerability with bravado. Her persona, honed through letters, photographs, and eventually books, becomes both her mask and her medium.

Despite professional breakthroughs like her Rolling Stone piece “The Sheik,” she struggles to separate literary validation from romantic acceptance, often confusing one for the other. Even her success is tainted by heartbreak and competition, as seen in the painful fallout with Dan Wakefield and the toxic spiral with Grover Lewis.

Sobriety and trauma bring a somber clarity to her later life. The disintegration of her friendship with Joan Didion marks a symbolic end to an era, and Eve’s near-fatal accident in 1997 becomes the final crucible of her transformation.

As she recovers in obscurity, she is rediscovered by a younger generation who finally appreciate the paradoxes she long embodied. Eve Babitz survives as a cult figure who blurred boundaries between art and life, seduction and satire, performance and confession.

Her legacy is not one of polished genius but of chaotic authenticity—a woman who turned her contradictions into literature, her heartbreaks into mythology, and her city into a canvas.

Walter Hopps

Walter Hopps emerges as a pivotal yet ultimately disappointing figure in Eve Babitz’s artistic formation. A key player in Los Angeles’s contemporary art movement, Hopps co-founded the Ferus Gallery and was instrumental in bringing the likes of Warhol and Duchamp to the West Coast.

Charismatic and visionary, he initially serves as a gatekeeper who introduces Eve to the artistic underground of Barney’s Beanery. He is both mentor and lover, providing Eve with cultural capital and personal intimacy.

However, his betrayal—excluding Eve from the Duchamp event in Pasadena in favor of his wife—marks the first major rupture in Eve’s romanticized view of male mentorship. The incident catalyzes Eve’s transformation into an icon through the famous nude chess photograph, essentially allowing her to reclaim the narrative by turning herself into art.

Hopps’s symbolic gift of a silver bullet instead of a ring further cements his role as a source of romantic and emotional devastation. Through Hopps, the text explores the recurring theme of male arbiters who hold the keys to artistic spaces while denying women full access—forcing Eve to subvert rather than enter.

Brian Hutton

Brian Hutton functions as the template for Eve’s sexual and emotional awakening. Their passionate, doomed affair becomes the foundation for her epistolary novel, Travel Broadens, wherein she experiments with voice, detachment, and sensuality.

Hutton, married and unattainable, represents the archetype of the emotionally distant lover whose absence creates fertile ground for artistic output. His refusal to commit haunts Eve, fueling both her sexual identity and her sense of inadequacy.

Yet, his presence in her writing is filtered through irony and satire, shielding the full emotional weight of the relationship from the reader. Hutton’s emotional unavailability deepens Eve’s confusion between longing and literary voice, ultimately leaving her oscillating between genuine heartbreak and stylized detachment.

Joan Didion

Joan Didion is both rival and reluctant mentor, a towering literary figure who casts a long shadow over Eve’s writing career. Initially supportive, Didion helps Babitz secure a book deal and even offers editorial guidance.

However, Eve gradually perceives this mentorship as suffocating rather than nurturing. The stylistic and philosophical chasm between them—Didion’s restraint versus Babitz’s exuberance—leads to a professional and emotional schism.

Eve “fires” Didion, believing her influence threatens to sterilize her distinctive voice. Their relationship exemplifies a complex female rivalry shaped by mutual admiration, latent envy, and differing visions of literary authenticity.

In the cultural imagination, Didion becomes the cool, distant chronicler of California, while Babitz embodies its unruly, sensuous counterpoint. Their contrasting trajectories highlight divergent responses to fame, grief, and creative control.

Dan Wakefield

Dan Wakefield represents another chapter in Eve’s pattern of romantic idealism followed by crushing betrayal. Initially supportive, he celebrates Eve’s literary success until her publication in Rolling Stone eclipses his own failed submission.

His abrupt and spiteful departure—underscored by the hurtful remark “I’ll see you on Johnny Carson”—unveils the fragile masculinity that crumbles in the face of female success. His quick rebound into a relationship with Eve’s friend further accentuates his emotional immaturity and lack of integrity.

Wakefield’s role, though minor, reinforces the recurring theme that many of Eve’s romantic partners were threatened by her brilliance, often reacting with cruelty masked as indifference.

Grover Lewis

Grover Lewis is both a catalyst and a cautionary tale. As a writer and editor at Rolling Stone, he initially helps elevate Eve’s literary reputation.

Their relationship, built on shared artistic sensibilities, quickly devolves into chaos due to Grover’s alcoholism and violent temper. The domestic implosion that leaves Eve physically evicted and emotionally shattered is emblematic of how creative camaraderie often curdles into emotional abuse.

Lewis’s presence underscores the dangers of blurring professional and personal lines, particularly for women whose survival often depends on male approval. His collapse into toxicity starkly contrasts with his early support, showing how easily admiration can turn into destruction when power dynamics shift.

Holly

Holly, though a peripheral figure, plays an essential symbolic role in Eve’s coming-of-age. As a high school friend and a tragic example of Hollywood’s broken promises, Holly represents the cautionary tale of wasted beauty and stardom gone sour.

Her drug use, emotional instability, and eventual obscurity mirror the fate awaiting many women lured by the illusions of glamour. For Eve, Holly is both a mirror and a warning—what happens when charisma is not coupled with control, when seduction fails to secure power.

Her presence early in the narrative sets the stage for Eve’s determination to outwit the system rather than be devoured by it.

Mirandi

Mirandi, one of the few emotionally nurturing presences in Eve’s life, provides a rare lens into Eve’s internal world. It is through Mirandi that readers learn of Eve’s deeper vulnerabilities—her devastation at rejection, her paralysis in the face of failure.

Mirandi functions almost as Eve’s emotional scribe, chronicling what Eve herself is too proud or too wounded to reveal. She provides an essential counterbalance to the emotionally withholding men in Eve’s life, emphasizing the importance of female friendship and emotional honesty in a world dominated by facades and performances.

Themes

Cultural Identity and Duality

The portrayal of Eve Babitz in Didion and Babitz underscores the theme of cultural identity as a layered, often contradictory force in a young woman’s life. Eve is born into an artistic lineage, with a home life steeped in classical music, fine art, and intellectual reverence.

Her godfather is Stravinsky, her parents part of an elite cultural enclave, and her upbringing unfolds in the mythic realm of Hollywood Hills—a world of dinner parties, studio orchestras, and avant-garde energy. Yet Eve’s soul is captivated by the synthetic shimmer of pop culture and lowbrow glamour: Hollywood High’s toilets, Rudy Valentino’s erotic mystique, and the buzz of bars like Barney’s Beanery.

This contrast defines her not as fragmented but as whole, embodying the refusal to choose between high and low. Her rebellion against the Thunderbird Girls, who epitomize 1950s femininity and its accompanying passivity, represents not just teenage defiance but a philosophical break from the binaries imposed on her.

Her embrace of cultural trash is an act of reclamation, her declaration that taste is not inherited—it is built. That duality becomes her signature and source of power, allowing her to move freely between intellectual and erotic spheres, and to challenge the artificial boundaries that aim to keep women confined to one or the other.

Self-Invention and Feminine Power

Eve Babitz’s journey is defined by the calculated and at times unconscious acts of self-invention that propel her from muse to artist. Her iconic nude chess photo with Marcel Duchamp is not simply a provocation but a statement: she positions herself at the intersection of sexuality and intellect, crafting a visual manifesto of who she is and what she refuses to be reduced to.

The shot is less about titillation and more about power—the audacity to exist in a space where male intellect once reigned, now occupied by a woman who refuses to cover herself but refuses, too, to smile. Similarly, her early letters that evolve into the novel Travel Broadens trace a different kind of self-construction: the birth of a literary persona.

That Eve is comic, aloof, and sometimes cruel is not an accident but a defense mechanism. She curates a version of herself that can survive rejection, heartbreak, and artistic failure.

Yet the persona costs her dearly, often muting the depth of emotion that defines her private experiences. The constant interplay between performance and authenticity becomes central to her artistry and identity.

Even her romantic entanglements with powerful men—Hopps, Hutton, Heller—are reframed not just as missteps but as fields of study and sources of raw material. She gathers power not in spite of her romantic experiences but through them, turning her wounds into wit and her heartbreaks into prose.

Artistic Legitimacy and Gender

A persistent tension in Didion and Babitz is Eve’s quest for artistic legitimacy in a world that distrusts beautiful, sensual women who wield humor and eroticism as tools of art. The essay shows how Eve’s body becomes both a weapon and a liability, both her currency and her cage.

When editors like Robert Gottlieb ask for “more,” they are not just critiquing her prose—they are questioning whether a woman who looks like Eve, who poses nude, who flirts, can also be taken seriously as a writer. Her early interactions with Joseph Heller highlight this paradox: she crafts her pitch with flair and seduction, only to be told that her work needs reshaping.

Yet her aesthetic is already deeply formed—it simply does not fit the masculine molds of literary success. The rejection she faces is not purely editorial; it is existential.

At every turn, she must prove that her sensuality does not negate her intellect. In doing so, she helps carve a space in the cultural landscape for women who refuse to disavow their femininity in exchange for credibility.

This theme crystallizes when she separates from Joan Didion’s influence, rejecting Didion’s cool detachment in favor of her own messy exuberance. Her refusal to be edited into sterility is not just about preserving voice—it is a feminist act.

Emotional Fragmentation and Public Persona

Much of Eve’s life as presented in the essay is shaped by an emotional duality: what she feels and what she performs. The tension between her inner turmoil and outer poise is illustrated most painfully in her relationships.

Whether it is Brian Hutton’s non-commitment or Walter Hopps’ betrayal, Eve is repeatedly made to mask vulnerability with wit, heartbreak with irony. The tragedy of Marilyn Monroe’s death devastates her, but in her writing it becomes an almost glib aside.

The detachment she adopts in Travel Broadens reads like armor—an unwillingness to expose wounds in a world that would only gawk. This emotional fragmentation reaches a visual apex in Charles Brittin’s 1966 photograph of her: no longer the composed, enigmatic subject of Duchamp’s chessboard, she looks adrift and out of sync, haunted rather than haunting.

Her inability to reconcile her private self with her public image becomes a recurring ache. This dissonance continues into her later years, where sobriety dulls her creative spark, and the cult of personality she had carefully constructed becomes a ghost of itself.

Eve’s story is thus not just about the construction of identity, but the cost of maintaining it, especially for women whose beauty becomes their burden and their talent their second act.

Power, Betrayal, and Female Rivalry

The complex interplay between Eve and Joan Didion frames one of the book’s most profound themes: the volatility of mentorship and the complicated dynamics of female rivalry. What begins as admiration morphs into dependence, then alienation.

Didion’s behind-the-scenes support—editing, deal-making, professional guidance—is essential to Eve’s initial success. Yet Eve begins to perceive that same support as a form of control.

She comes to believe that Didion’s influence is suffocating the vitality of her voice, pressing her toward literary respectability and away from the unruly, voice-driven prose that defined her originality. Their eventual break is not just professional—it is philosophical.

Where Didion values restraint, Eve thrives on exuberance; where Didion crafts narratives of cool detachment, Eve wallows in sensory excess. This rift represents a broader generational and stylistic shift, but also underscores the theme of betrayal, particularly in a world where women are often forced into scarcity mindsets.

Their falling out also reflects the impossible standard placed on women to both support and compete with one another, to collaborate and to outperform. Eve’s depiction of Didion in her fiction as humorless and rigid speaks not to simple animosity but to a deeper resentment toward a woman who succeeded by following rules that Eve was constitutionally unable—or unwilling—to obey.

Decline, Survival, and Reinvention

In the final chapters of her life, Eve Babitz becomes a symbol of survival—damaged but unbroken. After years of emotional implosions, addiction, romantic betrayal, and creative droughts, her journey veers toward both physical catastrophe and eventual cultural redemption.

Her decision to enter Alcoholics Anonymous at thirty-nine is less a retreat than a severing: a necessary move to preserve what’s left of her spirit. This choice, however, demands that she abandon the very communities that once defined her.

The fire accident in 1997 becomes a literal manifestation of her suffering, burning away her public image and leaving her vulnerable, dependent, and mostly forgotten. And yet, it is precisely in this state that her legacy begins to resurrect.

The rediscovery of her work by a new generation, led by Lili Anolik, affirms that survival is not just a passive state but a creative force. Eve outlives her relevance, her peers, and even her myth, only to be reborn through the very stories that once went ignored.

This reinvention is bittersweet: she is finally recognized, but too frail to fully enjoy the attention. Still, it is a testament to her singular power that even in decline, she shapes how we remember Los Angeles, femininity, and rebellion.

Her life becomes a case study in the cost of living authentically in a world that constantly punishes women for refusing to conform.