Heartbreak Is the National Anthem Summary and Analysis

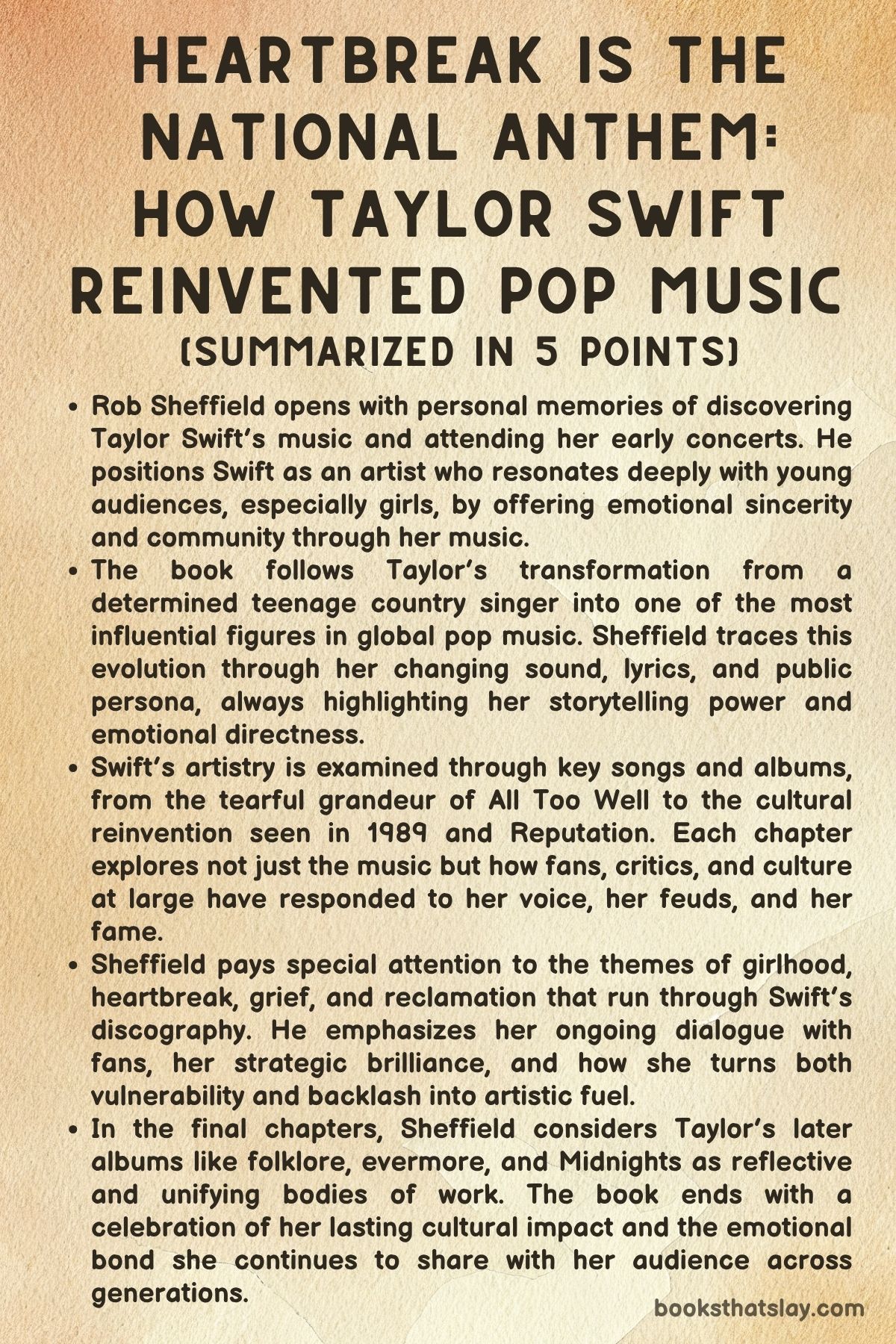

Heartbreak Is the National Anthem by Rob Sheffield is a deeply cerebral tribute to the cultural and emotional significance of Taylor Swift’s music. More than a fan memoir, the book functions as a critical reflection, a personal journey, and a cultural study, tracing the profound ways Swift’s evolving artistry has mirrored, shaped, and comforted her fans—especially through moments of vulnerability and transformation.

Sheffield’s writing, rich with personal anecdotes, sharp insight, and literary allusion, explores Swift not just as a pop icon but as a mythmaker, chronicler of feeling, and emotional historian for a generation. The book is both love letter and lens, inviting readers to feel, grieve, remember, and reimagine.

Summary

Heartbreak Is the National Anthem begins with a deceptively simple memory: the author, Rob Sheffield, hears Taylor Swift’s “Our Song” in 2007 while making a grilled cheese sandwich. That fleeting experience becomes a lightning rod moment, sparking what will evolve into a long-standing emotional and intellectual relationship with Swift’s music.

From this intimate beginning, Sheffield unfurls a sweeping narrative that tracks Swift’s meteoric rise and enduring influence—not just in the music industry, but in the cultural and emotional lives of her fans.

Sheffield is instantly captivated not only by Swift’s sound but by her authorship. At a time when most teen stars relied on songwriters, Swift’s creative control over her lyrics felt revolutionary.

Her debut didn’t just tell stories—it invited listeners to insert themselves into the emotional center of those stories. That early empowerment, especially for young girls, forms one of the book’s central threads: Swift as a voice of generational self-discovery, a lodestar of emotion and ambition.

As Swift transitions from country roots to pop superstardom, Sheffield follows. He attends a 2011 Speak Now concert and witnesses firsthand the ecstatic bond between Swift and her audience.

It’s not just a concert—it’s an initiation. The fans scream, cry, and sing along as if they are part of the narrative.

Sheffield positions this moment as pivotal: Swift has become more than an entertainer. She’s a conduit for shared experience, particularly among young women who find in her the courage to be loud, tender, angry, and unapologetically emotional.

One of the most profound meditations in the book centers on “All Too Well. ” Initially a five-minute ballad beloved by Swift’s most devoted fans, the release of the ten-minute version in 2021 recontextualizes the song into a cultural landmark.

Sheffield portrays this song as emblematic of Swift’s artistry: her refusal to silence or minimize emotional pain, her gift for transforming personal sorrow into universal catharsis. The scarf, the typewriter, the long drive—they aren’t just details; they’re relics of emotional truth, handed down like sacred text to a generation that has learned to define heartbreak through her lyrics.

This essay is as much about transformation as it is about music. Sheffield charts Swift’s evolution as a radical act of reinvention.

From the Red era’s genre-defying risk to the 1989 era’s glitzy pop declaration, Sheffield captures Swift’s conscious shift away from being seen as a sweet country ingenue to becoming a self-authoring icon. Her embrace of the synth-heavy sound of 1989, the creation of the infamous “Girl Squad,” and the exploration of feminine friendship in public discourse mark a deliberate move toward self-definition.

Even so, reinvention has its costs. The essay explores the backlash Swift faces—media scrutiny, slut-shaming, political pressure.

Her desire to be “nice” becomes a recurring theme, a coded term loaded with gendered expectations. Sheffield unpacks how Swift weaponizes this concept, using it ironically, sincerely, and critically throughout her lyrics.

Songs like “Begin Again” and “Bejeweled” become manifestos on how public figures—particularly women—must constantly navigate the thin line between likability and authenticity.

Swift’s so-called “Villain Era” provides another layer of introspection. The fallout from the Kanye West and Kim Kardashian feud, and the way it snowballs into cultural ostracization, marks a public low point.

Sheffield doesn’t minimize the drama but instead presents it as part of Swift’s ongoing battle to reclaim her narrative. In this darkness, she writes Reputation, an album brimming with aggression, vulnerability, and hidden tenderness.

Beneath the explosive synths lie love songs and laments—evidence that Swift never loses sight of emotional honesty, even when cloaked in armor.

Throughout the book, Sheffield returns to the symbiosis between Swift and her fans. He emphasizes how she doesn’t merely speak for her audience—she speaks as them.

In this way, she becomes more than a star; she becomes a vessel through which her fans explore their own feelings. Sheffield recalls watching Swift at the Tribeca Film Festival, where she speaks about the making of the “All Too Well” short film.

Her references to filmmakers and visual artists reveal a thoughtful creator who considers narrative and symbolism with the seriousness of a poet or director.

Phoebe Bridgers’ reflection on how Swift influenced her own songwriting reinforces the scope of Swift’s reach. For many artists, Swift legitimized the emotional turmoil of girlhood as a worthy artistic subject.

Her lyrics about insecurity, longing, and rage are not just cathartic—they are elevated to an art form. This feminist framing runs throughout the book, as Sheffield underscores Swift’s influence on a generation of women who found empowerment in storytelling, guitar-playing, and the act of being unashamedly emotional.

The book’s emotional core is reached in a section about “The Archer. ” Here, Sheffield reflects on the death of his mother and the strange solace he finds in Swift’s music.

The song, with its haunting lines about loneliness and identity, becomes a surrogate voice for his grief. It is not that Swift offers solutions or answers—she doesn’t pretend to.

Instead, she offers recognition. In Heartbreak Is the National Anthem, this act of recognition becomes the ultimate gift.

The ability to say, “I see you,” and be seen in return.

The final pages consider Swift’s legacy not in terms of awards or record sales but in the emotional archives she’s created. For Sheffield, being a Swiftie is about finding resonance in someone else’s voice and realizing it was your voice all along.

The book ends not with closure, but with invitation—an acknowledgment that Swift’s story, like the stories of her listeners, is still being written. Each new album, each new reinvention, becomes a chapter in an ever-growing saga of what it means to feel deeply and speak loudly.

In this way, Heartbreak Is the National Anthem becomes more than a tribute—it’s a communal biography of those who found their inner lives reflected in Swift’s lyrics. It’s about art that doesn’t just describe experience, but transforms it.

And it’s about how heartbreak, when sung loudly enough, becomes something transcendent—something national, something shared.

Key People

Rob Sheffield

Rob Sheffield serves not merely as the narrator of Heartbreak Is the National Anthem, but as the emotional core and lens through which Taylor Swift’s music is interpreted. His character unfolds as a deeply vulnerable, insightful, and emotionally literate fan whose relationship with Swift’s art is more than admiration—it’s a means of self-exploration and connection.

Sheffield is an experienced music critic, yet what stands out is not his critical detachment but his raw, unflinching emotional proximity to the music. His initial encounter with Swift’s “Our Song” is not described through a technical breakdown but as a near-religious moment, grounding his character as someone who seeks epiphanies in pop culture.

He confesses to the exhilaration of discovering that a teenage girl wrote her own songs, hinting at his lifelong reverence for authenticity and self-expression in music. Over the course of the essay, Sheffield’s relationship with Swift’s music evolves from fascination to spiritual kinship.

His attendance at her concerts is depicted as a form of pilgrimage, revealing how art becomes ritual. But perhaps his most poignant portrayal is found in his connection to “The Archer,” where he processes the grief of his mother’s death through the song’s melancholy introspection.

It is here that Rob transcends the role of commentator and becomes a proxy for Swift’s broader fanbase—those who find refuge, identity, and purpose in music that dares to feel too much. He is not simply a fan but a vessel of empathy, navigating grief, joy, awkwardness, and redemption through the anthems of someone else’s heartbreak.

Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift, as depicted in Heartbreak Is the National Anthem, is more than a pop star—she is a living text, an evolving myth, and a mirror to the emotional intricacies of modern life. Her characterization is multi-dimensional: a feminist rebel, a wounded romantic, a theatrical artist, and a confessional chronicler of pain.

What sets her apart is not just her musical prowess, but her fearless vulnerability and unwavering need to narrate her own story. From the outset, she is framed as a prodigy—sixteen years old and already writing her own songs—defying industry expectations and establishing herself as a singular creative force.

Over time, her transformation from a country ingénue to a pop auteur becomes a central narrative arc, symbolizing the power of self-reinvention. Her artistry is described as maximalist and confrontational, unafraid of contradiction or emotional excess.

Songs like “All Too Well” and “The Archer” highlight her gift for turning personal trauma into collective catharsis. Swift’s “too muchness”—her refusal to edit her emotions, her hunger for narrative control, her tendency to overshare—is presented as a strength, a rebellion against cultural scripts that demand female restraint.

Her flaws, including public feuds, lyrical pettiness, and early missteps, are not airbrushed but embraced as part of her mythos. These imperfections only deepen her connection with fans, who see in her a kindred spirit navigating the messiness of life with poetic bravado.

Ultimately, Swift emerges as an archivist of emotional truth, chronicling girlhood, grief, longing, and joy with both grandeur and grace.

Phoebe Bridgers

Although Phoebe Bridgers occupies a relatively minor role in Heartbreak Is the National Anthem, her inclusion carries significant thematic weight. She represents the lineage of young female artists who have not only been influenced by Swift but empowered by her confessional mode of songwriting.

Bridgers is not merely a fan; she is a peer in a newly expanded canon of women turning vulnerability into art. Her acknowledgment that Swift changed her approach to music by modeling radical honesty is a testament to Swift’s generational impact.

Through Bridgers, Sheffield illustrates how Swift’s influence is not just confined to fans but reverberates through the artistic community. Bridgers’s own music—often tinged with melancholy, introspection, and razor-sharp lyricism—mirrors Swift’s ethos, cementing her as both a disciple and a co-conspirator in the emotional revolution Swift helped spearhead.

Her character functions as a bridge between generations, demonstrating that Swift’s legacy is not static but evolving, passed down like a quill to the next group of storytellers unafraid to bleed on the page.

The Swiftie Community

Though not personified by a single individual, the Swiftie community is characterized in Heartbreak Is the National Anthem as a vital, pulsating character in its own right. For Sheffield, being a Swiftie is not just about musical preference—it is a mode of living, a collective identity built on shared emotional truths.

This fandom is described with reverence and complexity. It is depicted as a sanctuary for young girls discovering the power of their voices, but also as a broad church that includes grieving sons, queer listeners, and artistic aspirants.

The community finds itself in Swift’s “too muchness,” her openness, her contradictions. Swifties are not passive consumers but active participants—screaming their private anguish in unison at concerts, decoding lyrical easter eggs, and mapping their emotional growth onto Swift’s discography.

Sheffield portrays them as co-authors in the myth-making process, a crowd that transforms pop music into ritual and heartbreak into communion. The fandom becomes a mirror for Swift’s own evolution, and in turn, they evolve with her—growing braver, more articulate, and more attuned to their feelings through the stories she dares to tell.

Analysis of Themes

Fan Identity and Emotional Intimacy

The essay constructs a vivid portrait of fandom as an emotionally rich, lifelong relationship—one that matures and transforms in tandem with Taylor Swift’s own career. From the author’s first encounter with “Our Song” to the communal catharsis of “All Too Well (10 Minute Version),” the relationship is deeply personal, almost devotional.

Swift’s music isn’t just consumed—it is lived through, mourned with, and celebrated alongside. The bond is built on more than admiration; it is sustained by a mutual sense of recognition.

Fans don’t merely listen to Taylor Swift—they feel seen by her, often at their most vulnerable. Her songs articulate the unspeakable, offering both solace and solidarity.

This emotional transaction forms a feedback loop: the more Swift shares, the more her fans reflect themselves in her. The essay’s own narrative structure—part memoir, part cultural analysis—mirrors this interplay, suggesting that the true power of Swift’s music lies in how it becomes a scaffold for the listener’s own self-understanding.

Through grief, heartbreak, and triumph, Swift functions as a surrogate narrator for emotions too slippery to express otherwise. Fandom in this context becomes a mirror and a megaphone: it amplifies private pain and transforms it into a shared anthem.

To be a Swiftie is to belong not to a club, but to a collective memory. That memory may be etched in eyeliner and guitar strings, but it is just as often carved from real heartbreak, personal epiphanies, and a constant search for emotional resonance.

Artistic Transformation and Self-Reinvention

The narrative carefully maps Taylor Swift’s arc from a teenage songwriter to a cultural juggernaut, emphasizing her relentless pursuit of reinvention. Each artistic phase is not just a musical evolution but a deliberate recalibration of identity.

Swift’s transition from country roots to synth-pop chic in 1989, her symbolic retreat during public scandals, and her phoenix-like return with Reputation are framed not merely as career decisions but as assertions of autonomy. Reinvention here becomes an act of resistance—against industry expectations, gendered constraints, and media narratives.

The author makes it clear that Swift doesn’t passively adapt to change; she engineers it. Her willingness to court backlash, take artistic risks, and discard old versions of herself signals a deeper understanding of fame’s performative nature.

It is not about staying relevant—it’s about staying in control. Her transformation is also profoundly gendered.

The essay notes how terms like “nice” are weaponized against her, and how she reclaims them in her lyrics, performances, and public persona. Each reinvention is an act of self-definition, a refusal to let the world dictate the terms of her existence.

Even her mistakes become part of the myth-making machinery—contributing not to a linear ascent but to a jagged, more honest legacy. Through this, the essay argues that Swift’s greatest artistry lies not in melody or metaphor but in narrative control.

Reinvention isn’t just about new music—it’s about refusing to be cornered, even by your own past.

Cultural Legacy and Female Empowerment

The essay positions Swift not merely as a musical icon but as a cultural force whose influence extends well beyond chart-topping singles. Her presence reshapes the musical landscape, particularly for young women who see in her a blueprint for creative expression and self-assertion.

Her impact on guitar sales, lyricism, and fan culture is both measurable and symbolic. She becomes a conduit for female autonomy in an industry historically resistant to it.

The act of writing her own songs at sixteen—mentioned repeatedly in the narrative—is not just rare, but revolutionary. It sets a precedent for artistic authenticity that has inspired an entire generation.

The essay’s recollection of fans copying her lyrics onto their skin, or emulating her confessional songwriting style, speaks to a deeper cultural resonance: Swift is not just admired; she is emulated as a model of agency. Her feminist impact, though at times complicated and contested, is deeply embedded in how she navigates power, vulnerability, and public perception.

The essay carefully balances her flaws with her influence, suggesting that it is precisely her contradictions that make her a beacon. Her ability to be petty and poetic, calculated and spontaneous, fragile and fierce—these contradictions offer a template for embracing one’s full self.

By chronicling these tensions, the essay asserts that Swift’s legacy is not in perfection, but in permission: she gives her fans the permission to be complex, to be expressive, and to be unapologetically themselves.

The Politics of Public Image and Myth-Making

Swift’s career is shown as a constant negotiation between authenticity and image management. The essay makes clear that her public persona—meticulously curated yet deeply personal—is a battleground where narratives are contested and reclaimed.

From the backlash surrounding her feud with Kanye West to the critiques of her political silence in 2016, Swift is continually scrutinized through a lens of expectation, particularly gendered expectation. The notion of the “nice girl” becomes a recurring motif, a performance Swift both embodies and critiques.

Her relationship with public perception is not passive—it is active, sometimes even antagonistic. The short film for “All Too Well,” the scarf, the stylized typewriter—these are not just aesthetic choices; they are strategic symbols in the larger mythology she constructs.

The essay implies that Swift is acutely aware of the power of narrative control, using her music and media presence to shape not just how she is seen, but what she signifies. Even when mocked or misinterpreted, she absorbs critique and converts it into art.

Her so-called “petty” side becomes a form of self-defense—a refusal to be silenced, even at the risk of appearing excessive or emotional. In a media landscape that often punishes emotional transparency, Swift’s insistence on narrating her own story becomes a radical act.

The essay portrays her myth-making not as deception, but as survival. Each public feud, every coded lyric, and all the visual metaphors are tools in an ongoing campaign for narrative sovereignty.

Grief, Memory, and the Emotional Power of Music

Among the essay’s most poignant reflections is the role of Swift’s music in processing grief and preserving memory. The author’s account of listening to “The Archer” while grieving the loss of his mother elevates the emotional stakes of fandom into a deeply spiritual space.

Swift’s songs become more than background tracks—they transform into emotional companions that accompany the listener through life’s darkest corridors. Music becomes a vessel not for escape, but for confrontation: a way to face sorrow, articulate loss, and survive emotional collapse.

The essay underscores how Swift’s strength lies in her ability to crystallize complex, often contradictory emotions—jealousy laced with longing, rage tinted with regret—into lyrics that echo long after the final note. “All Too Well,” in both its original and extended versions, is emblematic of this emotional architecture.

It is not simply a breakup song but a memorial—an archive of pain that refuses to be sanitized or abridged. In honoring the full breadth of emotion, Swift gives her audience a mirror for their own suffering.

The essay suggests that this is her truest power: to remind us that memory is not linear, that grief does not follow rules, and that emotional truth is valid even when it’s messy. Through these reflections, the piece positions music not as therapy, but as witness.

Swift does not resolve grief—she honors it, amplifies it, and by doing so, allows her listeners to feel less alone in their own mourning.