I Am the Dark That Answers the Call Summary, Characters and Themes

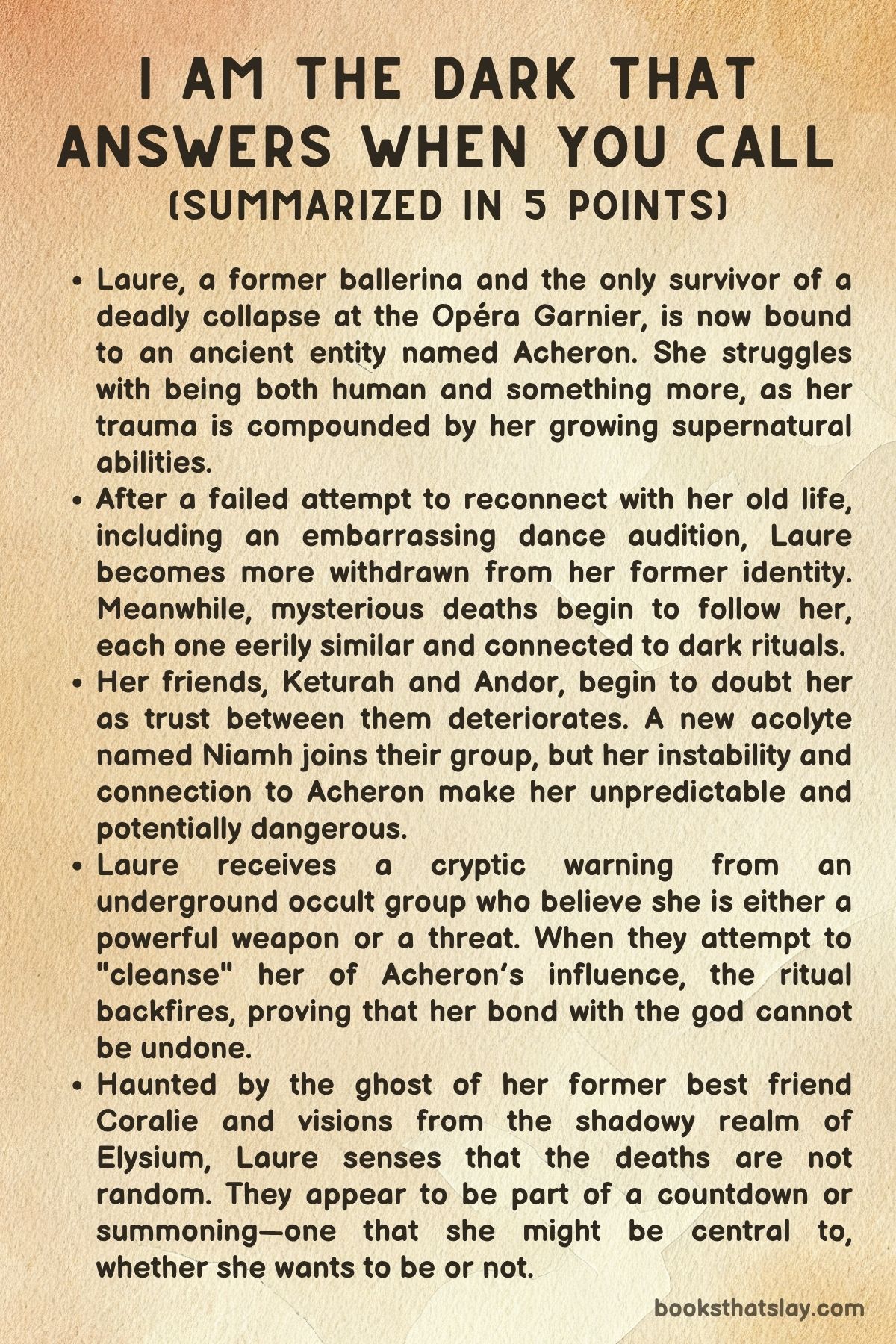

I Am the Dark That Answers the Call by Jamison Shea is a bold and emotionally charged dark fantasy set in modern-day Paris. Centering on Laure Mesny, a former ballerina who becomes the vessel for an ancient god named Acheron, the novel confronts trauma, identity, rage, and the blurred line between monstrosity and humanity.

As Laure navigates grief, supernatural entanglements, and shifting allegiances, her story unfolds with relentless emotional intensity and gothic sensibilities. Shea’s narrative explores themes of agency, transformation, and what it means to reclaim one’s self in the face of dehumanization, set against a beautifully ruinous backdrop of myth, memory, and vengeance.

Summary

Laure Mesny, once a ballerina, is now something far stranger and more powerful—a vessel for Acheron, an ancient eldritch god. The novel opens in a grief-stricken Paris, where Laure attends a memorial for those lost in the collapse of the Palais Garnier, including her former friend and rival, Coralie.

Though Laure survived the catastrophe, she is haunted by guilt and anger. The public sees her survival as miraculous, but she feels monstrous, harboring a growing inner voice—Acheron—whose whispers constantly tempt her toward revenge.

The world’s admiration for the dead, especially Coralie, contrasts sharply with its neglect of Laure, who is left to process her trauma alone.

Following the memorial, Laure attempts to lose herself in nightlife and fleeting pleasures, using drinking, clubs, and random hookups to numb her pain. But her escapism takes a sinister turn when she finds a girl she recently kissed dead in a bathroom, bearing signs of unnatural death.

Acheron dismisses the event, but Laure’s paranoia grows when she sees Niamh—another vessel she thought had left Paris—watching from the shadows. This marks the beginning of deeper mysteries: something darker is returning to the city, something that not even Acheron can name.

Retreating to Elysium, a supernatural forest ruled by Acheron, Laure seeks out Andor, her emotionally complicated companion. Their connection is strained by the horrors they’ve survived and the influence of their shared god.

Even in this supposed refuge, Laure is stalked by Coralie’s ghost, whose presence stirs confusion, grief, and lingering guilt. When Laure later attempts to reclaim her identity through an audition with a vaudeville troupe, she fails, confronting the painful truth that she is no longer who she once was.

This rejection underscores her isolation and fuels her growing fear of irredeemable transformation.

The tension escalates when Laure finds Niamh again. Niamh, now cold and secretive, reveals that she’s part of a broader collective of Acheron’s followers—vessels who operate beneath the surface of Paris.

She demonstrates a disturbing power to manipulate emotions, unnerving Laure. Despite this, their shared connection as Acheron’s chosen creates a tenuous bond.

Back in her day-to-day life, Laure continues to struggle with feelings of abandonment and betrayal, especially when her estranged mother suddenly reaches out. The emotional toll of that reappearance sends Laure into another spiral, only briefly tempered by the support of her friend Keturah.

As Laure tries to piece together her crumbling sense of self, Coralie’s ghost becomes more real, indicating that the line between the living and dead is deteriorating. This supernatural unraveling is paralleled by personal betrayals: Vanessa, a fellow dancer, reveals Laure’s secrets to others, and Niamh—now operating under the name Margaux—shows increasingly violent tendencies.

When Laure returns to Elysium, she finds the sacred glade dying, overtaken by the influence of Lethe, a parasitic force once wielded by Coralie. Even Acheron appears helpless against this encroaching rot.

As Laure’s dance career tentatively resumes, she receives a prominent role, giving her hope. But this fragile progress is shattered when she discovers a horrific scene: fellow vessels torturing a woman.

The event pushes Laure to use her powers to stop them, asserting her values in contrast to others who have fully embraced their monstrous capabilities. She begins seeking answers about the recent deaths, but is dismissed by police and authority figures.

As the city becomes increasingly destabilized, Laure’s emotional and physical safety disintegrate.

With the spread of Lethe corrupting both the forest and the city, Laure rallies with Keturah and Andor to investigate further. Their search leads them to a graveyard of bones and eerie spirits, where Laure meets a ghost of her former self.

This spectral version offers a chilling prophecy: oblivion is coming. As Laure tries to warn the others, Margaux reveals her fully godlike form, dominating and sadistic.

She kills Vanessa in a display of absolute power, then turns on Laure. Brutally beaten and left for dead, Laure experiences Acheron’s silence for the first time.

Abandoned even by her god, she is buried alive.

What follows is Laure’s rebirth—not through divine intervention, but through pure, raw will. She claws out of the earth, confronting her trauma, her ghosts, and her despair.

This moment marks a shift: Laure is no longer a pawn or vessel—she is something entirely her own. She discovers that Andor, believed dead, has been resurrected by Elysium, now bearing the mark of an asphodel flower, a symbol of hope.

Their reunion is brief, however, as they return to a Paris on the brink of destruction. Margaux has taken over the Palais de Justice in a symbolic act of rejecting mortal systems.

In a final confrontation, Andor uses his newfound powers to destroy Dominique, one of Margaux’s most loyal followers. Laure confronts Margaux and the others, revealing the full extent of her transformation.

She is no longer just Acheron’s conduit—she is godlike in her own right. Her power radiates through the city, terrifying her enemies into submission.

She spares Margaux, a choice that asserts her moral agency and draws a clear boundary between domination and autonomy.

The novel closes on Laure walking away from the ruins, not seeking approval or redemption. She is no longer a hero, not a villain, but something undefined—something self-chosen.

Her journey is one of reclamation: of power, voice, and identity. In a world that tried to shape her through pain, Laure becomes her own myth.

I Am the Dark That Answers the Call is ultimately a story of surviving the unbearable, choosing one’s path, and wielding darkness without being consumed by it.

Characters

Laure Mesny

Laure is the fractured and fiercely complex heart of I am the dark that answers the call, a character in perpetual negotiation with grief, trauma, identity, and monstrosity. Formerly a ballerina, Laure’s transformation into a vessel for the eldritch god Acheron fractures her connection to the human world while amplifying her emotional and psychological vulnerability.

She is both victim and survivor of a horrific collapse at the Palais Garnier, haunted not only by the dead but by the guilt of having survived. Throughout the novel, Laure navigates a tension between the divine power coursing through her and the fragile humanity she clings to—embodied in her sorrowful visits to memorials, her hedonistic nightclub escapism, and her strained friendships.

She is constantly torn between Acheron’s seductive whisper for vengeance and her own desire to maintain a moral compass. What makes Laure compelling is not her supernatural capacity but her resistance to it—her refusal to give into godhood for the sake of retaining emotional integrity.

Her character is haunted in every sense: by ghosts, by her past, by guilt, by her dead friend-turned-tormentor Coralie, and even by a younger version of herself who acts as a symbolic mirror to all she has lost. Laure’s ultimate transformation into a godlike being is not a complete surrender but an act of self-definition; she seizes monstrousness on her own terms.

In the end, she is no longer merely a vessel—she becomes a force of her own making, autonomous, merciless, yet still capable of compassion, and it is that contradiction that defines her.

Acheron

Acheron, the eldritch deity that lives within Laure, functions as both power and parasite. He is an entity of ancient, unknowable darkness who offers Laure incredible capabilities—resurrection, manipulation of the environment, and violent retribution.

Yet his presence is never passive; he is an ever-whispering shadow in Laure’s mind, representing the seductive nature of unchecked power. He is not a villain in the traditional sense, but an embodiment of temptation and primal justice, constantly nudging Laure toward monstrous solutions.

Acheron’s interactions with Laure are invasive yet intimate, at times protective, other times cruel. His weakening over the course of the novel mirrors Laure’s growing independence, suggesting that his power is not merely magical but psychological, bound to Laure’s self-perception.

When he fails to intervene during Laure’s most brutal suffering—particularly when she is beaten and buried—his silence marks a rupture in their symbiosis. By the novel’s end, Laure supersedes him, no longer merely hosting Acheron’s essence but transcending it entirely.

Thus, Acheron becomes a symbol of the transitional self—an entity both essential to Laure’s transformation and ultimately outgrown.

Niamh / Margaux

Niamh, later revealed to be Margaux, is Laure’s mirror in power but her antithesis in morality. Initially reintroduced as a fellow Acheron vessel and once-close companion, Niamh is seductive, distant, and increasingly aligned with sinister forces.

Her ability to manipulate emotion is not just a magical trait but an emotional weapon, and she uses it to gain followers, build power, and ultimately enforce dominance. As Margaux, her full transformation into a godlike force is chilling; she sheds all semblance of human restraint and empathy.

She is ruthless in her dealings with both enemies and allies, executing Vanessa without hesitation and orchestrating the brutal downfall of Laure. Margaux’s arc traces the trajectory of what Laure could have become had she embraced godhood without resistance.

Her ultimate defeat is significant not only for its tactical implications but because it reaffirms the novel’s central conflict—power unmoored from compassion is not liberation, but tyranny.

Andor

Andor is both a romantic interest and emotional anchor in Laure’s disorienting journey. A fellow vessel of Acheron, he shares a complicated history with Laure that oscillates between tenderness and guarded restraint.

Where Laure teeters on the edge of emotional disintegration, Andor offers a fragile stability, reminding her of the person she used to be and the possibility of human connection beyond pain. His death at Salomé’s hands is a harrowing rupture, yet his miraculous resurrection through the grace of Elysium—marked by an asphodel flower, a symbol of rebirth—becomes a turning point in the narrative.

With his return, Andor is no longer simply Laure’s lover or peer; he becomes a symbol of hope reborn through death. His renewed strength allows him to take an active role in Margaux’s defeat, and his survival affirms the novel’s belief in second chances and enduring love, even in a world steeped in horror.

Coralie

Coralie is perhaps the most haunting figure in the novel, both literally and metaphorically. In life, she was Laure’s best friend turned cruel antagonist, embodying toxic beauty, manipulation, and betrayal.

Her death in the Palais Garnier collapse does not end her influence; instead, she becomes an ever-present ghost who torments Laure with memories, accusations, and chilling insights. As a specter, Coralie is more than a shade—she is guilt incarnate, constantly reminding Laure of everything she has lost and failed to protect.

Her appearances are not just psychological hauntings but supernatural interruptions, forcing Laure to reckon with her own complicity and cowardice. In the climactic burial scene, it is Coralie’s taunting that ignites Laure’s rebirth, making her an unwitting midwife to Laure’s transformation.

Though cruel and merciless, Coralie’s ghost plays a pivotal role in shaping Laure’s final awakening, making her a figure of profound narrative importance.

Keturah

Keturah serves as Laure’s emotional refuge and conscience, a grounding presence amid escalating chaos. Their bond is deeply affectionate, underpinned by history and unspoken emotional currents.

Keturah’s unwavering loyalty provides Laure with a sense of belonging that even Acheron cannot match. Unlike many others, Keturah neither idolizes nor fears Laure, but meets her where she is—with honesty, care, and challenge.

She is one of the few characters who pushes Laure to reclaim agency and stop relying on divine intervention. Her capture during the climax and subsequent suffering are among the novel’s most emotionally charged moments, revealing how much Laure values her.

Keturah is not a warrior or god, but her strength lies in her emotional wisdom and moral clarity, making her a key figure in Laure’s navigation of power and selfhood.

Vanessa

Vanessa occupies a minor yet emotionally charged role. Initially seen as a mysterious, bruised peer, she becomes a symbol of human fragility within the god-dominated world.

Her interactions with Laure are fleeting yet impactful—she triggers both concern and jealousy, especially in relation to Margaux. When she betrays Laure by revealing her secrets, her motivations remain ambiguous—perhaps fear, perhaps desperation.

Her gruesome death at the hands of Margaux and Dominique is a pivotal moment, revealing just how far Margaux has strayed into cruelty and how meaningless human life has become to her. Vanessa’s death serves as a reminder of the stakes Laure is fighting against: the annihilation of human vulnerability and connection in the face of godlike tyranny.

Gabriel

Gabriel is an enigmatic figure throughout the novel, his loyalty often in question. A dancer and fellow vessel, his interactions with Laure are marked by cold professionalism that eventually gives way to deeper involvement.

He provides Laure with key opportunities—like a solo role—that suggest belief in her potential, yet his motivations are often unclear. His presumed death after being cast into Lethe is an ambiguous moment, marked more by narrative utility than emotional resonance.

Gabriel functions primarily as a narrative hinge—an informant, an instigator, and perhaps a cautionary figure. His cold detachment contrasts with Laure’s raw passion, making him an interesting foil, if not a deeply explored character.

Salomé and Dominique

These two characters represent the monstrous potential of unrestrained godhood. As followers of Margaux and fellow vessels, they indulge in torture, murder, and domination without hesitation.

They symbolize what happens when divine power is wielded without conscience or humanity. Their brutal acts—particularly Dominique’s murder of Vanessa and Salomé’s slaying of Andor—are acts of horror designed to test Laure’s boundaries and provoke transformation.

Ultimately, they are vanquished not just physically but morally, as Laure and Andor’s restraint and compassion cast their cruelty into even starker relief. Their deaths are not just victories in battle, but affirmations of the kind of power Laure chooses to wield.

Themes

Grief and Survivor’s Guilt

Laure’s experiences in I am the dark that answers the call are haunted by an ever-present undercurrent of grief and the unique torment of surviving a disaster that claimed others. Her survival of the Palais Garnier collapse is not framed as a blessing but as a curse that isolates her from the world she once belonged to.

Rather than being celebrated, she is burdened by others’ projections, seen as either a miraculous survivor or an unnatural being touched by darkness. This dichotomy leaves Laure feeling alienated and fractured, especially as she grieves for Coralie, a friend-turned-nemesis who perished in the collapse.

The complicated nature of their relationship—riddled with betrayal, pain, and unresolved tension—adds a layer of emotional ambiguity that deepens Laure’s guilt. She mourns not just the dead but the pieces of herself that died with them.

Her need to find meaning in her survival is palpable, especially as she resists Acheron’s seductive promises of revenge. The memorial scenes and her interactions with Rose-Marie emphasize society’s shallow engagement with grief—honoring the beautiful and socially palatable while forgetting those left behind in broken pieces.

Laure’s struggle is not merely with loss, but with the act of living after it. She wanders through clubs and cities, detached and aimless, seeking a way to exist in the aftermath.

This grief is not linear or clean; it tangles with memory, rage, and supernatural unease. Laure’s journey is defined by the way she learns to live with this pain, to carry it without succumbing to it or allowing it to erase her humanity.

Identity and Transformation

Laure’s arc is defined by a profound metamorphosis, not only through her rebirth as Acheron’s vessel but through her emotional, moral, and physical shifts as she navigates a world that no longer makes sense to her. The body that once danced with poise now trembles with divine rage, and her mind is no longer her own, always sharing space with a god whose motives blur the lines of agency and will.

The transformation she undergoes is not merely supernatural—it’s existential. Laure is forced to reevaluate who she is without ballet, without Coralie, without the safety of anonymity.

Each encounter—whether with her estranged mother, her estranged ghost of a self, or her former peers—challenges the notion of who she was and who she can become. Her auditions at Maison Lumina and attempts at connection with others like Andor, Keturah, and even Vanessa represent efforts to reclaim fragments of her former identity, but those fragments never quite fit into the person she is now.

The more she tries to reinsert herself into her past, the more she realizes it no longer defines her. And yet, this transformation is not presented as an empowerment fantasy.

It’s painful, filled with missteps and horror, often accompanied by an overwhelming sense of dislocation. Only when she chooses to rise from her own grave not for a god or a cause, but for herself, does Laure truly become someone new—an entity defined not by the power she was given, but by the choice she made to wield it on her own terms.

Power, Corruption, and Moral Boundaries

Power in I am the dark that answers the call is never neutral—it always extracts a cost. Laure’s connection to Acheron grants her extraordinary abilities, but also forces her into constant confrontation with her ethics.

The question of whether power inevitably corrupts is embodied in characters like Margaux (formerly Niamh), whose embrace of godhood leads to acts of domination and cruelty that Laure finds abhorrent. This stark contrast becomes a mirror for Laure’s fears: if she uses her powers, will she become like Margaux?

Her refusal to punish Vanessa even after betrayal, her horror at the cruelty inflicted by fellow vessels, and her continued resistance to Acheron’s darker whispers show how fiercely she clings to her moral center. Yet the story acknowledges how exhausting this stance is.

Laure is punished for her mercy, her boundaries constantly tested by a world that does not reward restraint. The death of Andor, the capture of Keturah, and her own brutalization reveal how power structures—be they divine or mortal—thrive on violence and domination.

When Laure finally unleashes her full strength, it is not a fall from grace but a redefinition of what power can be. She does not seek control or revenge but asserts the right to decide, to protect, to resist dehumanization.

The theme interrogates the nuances of power—not just its presence, but its purpose. It asks what it means to wield immense strength while remaining tethered to empathy, and whether goodness can survive when power is the only language anyone seems to understand.

Alienation and the Longing for Connection

From the very beginning, Laure is positioned as an outsider—alienated from her old life, from her friends, from the world of the living. Her role as Acheron’s vessel isolates her emotionally, socially, and spiritually.

Her attempts at reconnection often falter: her relationships with Andor and Keturah are marked by mistrust, her interactions with the acolytes reveal how different she is from those who have fully given themselves over to the divine, and even her own memories betray her with the presence of a ghostly Coralie who accuses and haunts rather than soothes. Laure’s craving for connection drives many of her decisions, yet each attempt is met with barriers—either from within herself or imposed by others.

The tension between the need to be understood and the impossibility of it is central to her alienation. Even when she finds brief moments of warmth—like Keturah’s support or Andor’s love—they are always tinged with the fear that these bonds are too fragile to last.

The story continually shows how supernatural transformation can alienate even the most grounded soul, turning friendships into suspicions and love into a liability. Laure’s ultimate reconnection—with Andor after his resurrection and with herself after clawing out of her grave—is a profound statement.

It suggests that connection must be chosen, not inherited or demanded. Her decision to walk away with power in hand, yet still willing to love and spare her enemies, shows that connection is not about being accepted by the world, but about refusing to let that world dictate your capacity for empathy.

Rebirth and Self-Actualization

Rebirth in I am the dark that answers the call is both literal and metaphorical. Laure’s resurrection as Acheron’s vessel is the catalyst for a journey that strips her of everything familiar.

The first death—the collapse at Palais Garnier—destroys her past life as a dancer and begins a long, painful excavation of who she truly is. But her true rebirth occurs not when Acheron pulls her back from death, but when she decides to live again after being buried alive by Margaux.

That moment is a culmination of all her pain, betrayal, and disillusionment, transmuted into sheer willpower. It is a choice to become something new—not a puppet, not a martyr, but a sovereign force.

Rebirth here is not passive or divine—it’s an act of defiance and self-actualization. Laure rejects the expectations of every force that has tried to define her—be it society, divinity, or trauma.

She does not emerge unchanged; instead, she carries every scar with her and transforms them into strength. The asphodel mark on Andor, the return to a decimated Paris, and the symbolic destruction of the Palais de Justice all signal a world being rebuilt from ruins.

Laure’s final form—terrifying, powerful, yet compassionate—is not a return to innocence but a testament to evolution. This theme positions rebirth not as a cleansing but as an integration of past, pain, and power.

It is about forging identity in the ashes of what was lost and stepping forward without apology, entirely and completely oneself.