I Do With You Summary, Characters and Themes

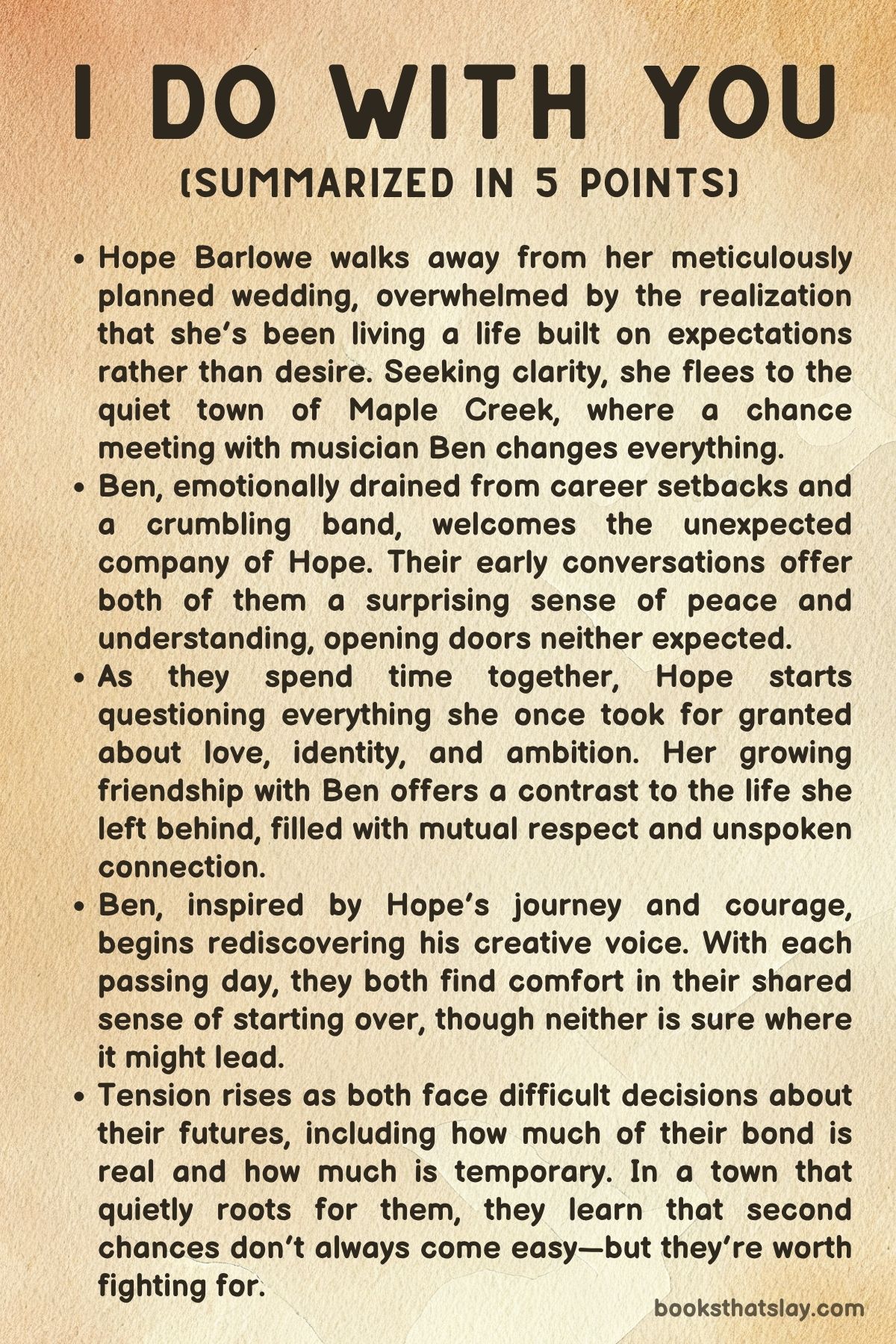

I Do With You by Lauren Landish is a modern romance about self-discovery, emotional freedom, and the courageous defiance of expectations. At the heart of this emotionally charged story is Hope Barlowe, a woman who makes a shocking but empowering decision to walk away from a life that looks perfect on paper but feels hollow to her soul.

Through her unexpected encounter with Ben, a world-weary rock musician seeking peace in anonymity, Hope begins to unravel the tightly wound identity she has long conformed to. What begins as a runaway bride story blossoms into a tale of healing, passion, vulnerability, and the messy beauty of choosing one’s own path—no matter how unconventional it may seem.

Summary

Hope Barlowe has spent her entire life walking the straight line of duty, reliability, and structure. On the day of her wedding to Roy Laurier—her high school sweetheart and the embodiment of a stable future—Hope is overwhelmed by a gnawing sense of unease.

Her childhood dreams, carefully constructed plans, and unwavering loyalty suddenly feel more like a cage than a comfort. As she prepares to walk down the aisle, the pressure builds until she makes an impulsive but deeply rooted decision: she runs away, abandoning the ceremony mid-vow in front of friends, family, and her would-be husband.

Hope’s frantic escape leads her into the woods and straight into the path of Ben, a reclusive rock musician on a self-imposed hiatus from the chaos of fame. Their meeting is abrupt, strange, and oddly serendipitous.

Ben offers her a moment of refuge—his trailer a haven from the whirlwind she just escaped. Despite barely knowing each other, a quiet understanding develops between them.

Over simple meals, late-night talks, and music that seems to speak directly to Hope’s confusion, the two find solace in one another’s broken places. Ben’s empathy and non-judgmental nature become the emotional salve Hope didn’t know she needed.

As the days unfold, Hope begins to reckon with the truth of her unhappiness. Her panic wasn’t a fluke, and her actions weren’t impulsive.

They were the result of years of conforming to a life plan that was never truly hers. With Ben’s support and emotional honesty, Hope allows herself to grieve—not just the end of her relationship with Roy, but the version of herself she no longer wishes to be.

Their connection, born from unexpected timing, deepens with quiet intensity. Ben, too, begins to examine the emotional stagnation he’s been hiding behind with his music career, and finds in Hope a mirror to his own buried longings.

When Hope returns to town for a confrontation with her twin sister Joy, she is met with hard truths that force her to re-evaluate her relationship with Roy. Joy’s candor reveals what Hope had tried to ignore: Roy represented safety, not passion, and Hope’s love for him had faded into obligation.

The visit, while painful, becomes a turning point. Rather than feeling ashamed for running, Hope begins to feel justified.

Her evolution gains traction when she visits the local diner and finds the town’s quiet but clear support for her autonomy. Even Rosemary, the diner owner, lies to Roy’s father—the sheriff—to shield Hope.

For the first time, Hope sees her decision as brave, not disgraceful. She formally ends things with Roy in a tearful but resolute phone call, shedding the last remnants of the role she had once been so determined to play.

Her emotional independence grows, particularly in moments of levity and affection with Ben, such as a tender lake scene where her rediscovery of desire is met with his gentleness and respect.

Hope later confronts Roy in person, and her clarity is unwavering. She expresses her truth unapologetically, acknowledging that the life he envisioned for them was suffocating.

His angry reaction only confirms that she made the right choice. In contrast, Ben’s kindness and respect continue to affirm her newfound self-worth.

Hope is no longer the girl who silently follows rules. She’s becoming a woman who asserts boundaries, prioritizes her emotional health, and seeks connection built on mutual understanding.

Hope’s transformation continues as she burns symbolic reminders of her “Good Girl” past and dares to show up publicly with Ben in Maple Creek. The bar scene, loaded with eyes and whispered judgments, becomes a statement.

She doesn’t shrink from the scrutiny. Instead, she owns her choices—flirty dress, flirtier attitude, and all.

With her siblings Joy and Shepherd backing her, and Ben by her side, she steps into this new version of herself with boldness.

That night, after one too many drinks, Hope leans into her flirtation with Ben. He, in turn, lovingly sets boundaries and cares for her with tenderness.

The next morning, their emotional intimacy blossoms into physical affection, marking a key milestone in Hope’s journey to reclaim her body, her desires, and her autonomy. In Ben, she finds a partner who honors her evolution, not someone who clings to who she used to be.

Their day trip downtown is filled with surprises—curiosity from townspeople, a meaningful encounter with a former teacher who reminds Hope of her once fearless nature, and finally, a confrontation with Roy. His desperate romantic gesture and jealous outburst devolve into violence.

Ben defends Hope and is arrested, a painful consequence that reinforces the stakes of Hope’s choices. Still, her faith doesn’t waver.

She’s not the same person who once feared shaking things up. Now, she stands firmly for herself and those she loves.

The emotional high point of the story is Hope’s heartbreak upon discovering Ben’s secret identity as a famous rock musician. She feels betrayed, questioning the authenticity of their bond.

Her pain is raw, compounded by the shadows of her past with Roy. But this time, rather than wallowing or shutting down, Hope leans into healing.

She journals, redecorates, spends time with loved ones, and reflects deeply. Her process is imperfect but intentional, and she refuses to lose herself again.

Ben, equally devastated, pours his sorrow into music. His new album becomes a soulful confession, every lyric echoing his regret and longing for Hope.

He battles industry pressure to stay true to his feelings, insisting on keeping a track named “Hope” despite commercial doubts. His vulnerability, expressed through his art, becomes a bridge between them.

His bandmate Sean, seeking redemption, invites Hope to a secret show in LA.

Hope attends, and in the thunderous passion of Ben’s music, she hears the truth: his remorse, his love, and his willingness to change. Their reunion backstage is heartfelt and intense.

Apologies and promises are exchanged, not in the naive hope of a perfect future, but in the brave commitment to try again.

The epilogue finds them not in a fantasy but in a life they’ve built together—flawed, unpredictable, and beautiful. Hope travels with Ben and his band, forging friendships and embracing the unknown.

They’ve both evolved—not because love saved them, but because they saved themselves and chose love anyway. Together, they continue to choose one another, rewriting their story not according to tradition, but according to their own truths.

Characters

Hope Barlowe

Hope Barlowe is the emotional nucleus of I Do With You, undergoing a profound transformation from a woman imprisoned by social expectations to someone fully inhabiting her autonomy and desires. At the story’s outset, Hope embodies the quintessential image of the “good girl”—organized, agreeable, and self-sacrificing.

Her life is a blueprint curated by familial pressures and societal norms, anchored in a long-standing relationship with her high school sweetheart Roy. However, the more Hope prepares for her wedding, the more she becomes consumed by internal dread.

Her dramatic flight from the altar isn’t impulsive—it’s a visceral reaction to the suffocating predictability of a life she never chose for herself. This act of rebellion marks the beginning of her emotional emancipation.

Her journey is not linear; she stumbles through confusion, panic, and vulnerability. Meeting Ben acts as a catalyst for her introspection.

With his support, Hope slowly sheds her need for approval and begins exploring who she truly is when she’s not performing for others. Her growth is illustrated through a series of increasingly bold decisions—from confronting her sister and ex-fiancé, to embracing her sexual agency, to publicly rejecting the expectations that once confined her.

Even after a painful betrayal from Ben, she chooses self-respect over dependency, demonstrating an inner resilience that defines her arc. Ultimately, Hope evolves into a woman who makes deliberate, confident choices, not because they are safe or expected, but because they align with her authentic self.

Ben

Ben is a compelling figure of emotional depth and transformation, a man defined not only by his troubled past but by his capacity to love, reflect, and change. When first introduced, Ben is a brooding, emotionally burned-out rock musician seeking refuge in nature from his chaotic life.

He’s sarcastic, guarded, and seemingly jaded, but his encounter with Hope awakens a side of him that had long been dormant. He offers her kindness, space, and understanding—qualities that sharply contrast with his public persona.

As their relationship evolves, Ben becomes more than a romantic interest; he is a mirror to Hope’s evolving sense of self. At the same time, Hope becomes a catalyst for Ben’s own emotional growth.

Her presence disrupts his emotional stagnation, compelling him to confront his failures, his guilt, and the disconnection from his own identity. His biggest misstep—concealing his rockstar status from Hope—springs from fear of rejection, not malice, yet it nearly destroys the bond they’ve built.

Ben’s journey after Hope’s departure is one of quiet agony and creative rebirth, pouring his emotions into a deeply personal album that acts as both confession and catharsis. His refusal to commercialize his most vulnerable song shows his commitment to truth, even when it costs him.

By the end, Ben stands not as a savior or fantasy, but as a flawed man striving for honesty and emotional maturity. His reunion with Hope is not a triumph of romance, but a testament to the hard-earned growth of two people choosing each other authentically.

Roy Laurier

Roy Laurier serves as both a relic of Hope’s past and an embodiment of the societal expectations she ultimately rejects. Presented initially as the dependable high school sweetheart and presumed “perfect match,” Roy represents safety, tradition, and small-town values.

However, beneath the surface of their relationship lies emotional inertia and a quiet power imbalance. Roy is not overtly abusive or villainous, but his expectations of Hope are steeped in control and ego.

He envisions a life in which Hope plays the agreeable wife role—supportive, predictable, and subordinate to his ambitions. His inability to truly see or hear her emotional distress highlights his limitations as a partner.

When Hope finally leaves him, Roy’s mask slips. His subsequent behavior, especially the jealous public confrontation and violent altercation with Ben, reveals a darker side defined by entitlement and emotional immaturity.

Rather than respecting Hope’s decision, Roy lashes out, weaponizing shame and social power. His character arc doesn’t develop much; instead, he becomes a fixed point against which Hope defines her freedom.

Roy’s greatest contribution to the narrative is in what he lacks: emotional depth, self-awareness, and the willingness to grow. In contrast to Ben’s evolving emotional intelligence, Roy remains rigid—a cautionary tale of what life might look like had Hope stayed.

Joy Barlowe

Joy Barlowe, Hope’s twin sister, adds complexity and grounding to the narrative. At first glance, she’s brash, sarcastic, and unfiltered—the opposite of Hope’s overly cautious persona.

Joy’s tough love and sharp wit serve as both a shield and a compass. While she doesn’t always deliver her insights gently, her motivations are rooted in deep familial loyalty and an earnest desire to see her sister happy.

When Hope flees her wedding, Joy is one of the few people willing to confront the uncomfortable truth rather than simply condemn or excuse her actions. She calls out the flaws in Hope’s relationship with Roy, challenging the romanticized vision that everyone else clings to.

Throughout the story, Joy acts as a necessary disruptor. Her fierce protectiveness manifests in her interactions with Ben, where she oscillates between skepticism and support, always prioritizing her sister’s well-being.

As Hope begins to forge her own identity, Joy’s presence becomes a sounding board—sometimes adversarial, often supportive, and always honest. What makes Joy especially memorable is her emotional transparency; she doesn’t hide behind politeness or pretense.

She grows in her own way too, learning to trust Hope’s decisions even when they diverge from her instincts. In many ways, Joy is the moral anchor of the story, embodying the love that challenges rather than enables.

Shepherd Barlowe

Shepherd Barlowe, the elder sibling of the Barlowe family, plays a more understated but impactful role in the emotional scaffolding of the story. He represents a grounded, masculine presence who neither imposes nor judges.

Shepherd’s loyalty is shown through action rather than sentiment. When he supports Hope at the bar or subtly affirms her connection with Ben, it is done without fanfare or pressure.

His dynamic with Ben, characterized by humor, shared interests like hockey, and even a light-hearted acceptance of Ben into the family circle, contrasts with the hyper-masculine aggression displayed by Roy. Through Shepherd, the novel introduces an alternative version of manhood—one rooted in emotional intelligence, respect, and quiet strength.

Shepherd’s support helps normalize Hope’s rebellion within the family unit and gives her the confidence to stand firm in her choices.

Brooklin

Brooklin, the waitress at Chuck’s bar, may appear to be a minor character, but she plays an important symbolic role in I Do With You. She embodies the judgmental gaze of small-town society—the whispering voices that shame women who deviate from traditional roles.

Her disapproval of Hope, particularly in public settings, serves as a counterpoint to the community support Hope receives from others. Brooklin represents the internalized misogyny and social rigidity that Hope is trying to escape.

Her silent sneers and passive-aggressive glances reflect a society more invested in appearances than personal happiness. Yet Brooklin’s importance lies in what she fails to do: grow or adapt.

Unlike Hope, who reclaims her agency, Brooklin remains stuck in silent bitterness, making her a static but telling figure in the broader narrative of transformation and resistance.

Deputy West

Deputy West offers a fascinating glimpse into the quiet undercurrents of resistance within a corrupted system. In a world where Sheriff Laurier holds undue sway, West’s subtle warning to Hope to keep running is a breath of unexpected support.

He doesn’t overtly rebel, but his coded language and refusal to enforce biased authority show that not everyone in power is complicit. His character is emblematic of hidden allies—those who work from within to subvert injustice.

While his role is brief, it is deeply meaningful. It reassures Hope (and the reader) that support can come from the most unlikely places.

West’s presence affirms the novel’s broader message: liberation often requires not only personal courage but also the quiet, strategic defiance of others in the system.

Sean

Sean, Ben’s bandmate, occupies a complicated space in the narrative as both betrayer and redeemer. His decision to reveal Ben’s identity to Hope acts as the catalyst for the story’s central emotional rupture.

At first, Sean seems to embody the careless recklessness of the rock-and-roll world, oblivious to the emotional consequences of his actions. However, his later choices—especially inviting Hope to Ben’s concert—suggest a deeper understanding and perhaps guilt.

He becomes a surprising agent of reconciliation, facilitating the emotional climax of the novel. Sean is a reminder that even those who falter can help repair what’s broken, and that growth can manifest not only in grand gestures but in quiet acts of humility and understanding.

Themes

Self-Liberation and Identity

Hope Barlowe’s emotional journey in I Do With You is a vivid portrayal of self-liberation born from internal conflict. She begins the story bound by the weight of familial expectation and social tradition—her life meticulously planned out with a stable fiancé, a defined career path, and a vision of the “perfect” domestic life.

But these plans are not hers in spirit. They are inherited ideals, adopted more from obligation than desire.

The moment she runs from her wedding, leaving behind a life that had been prewritten, marks the first act of personal revolution. It’s not just an impulsive escape; it’s the eruption of years of suppressed misalignment between what she truly wants and what she’s been told she should want.

Her initial collapse in the woods and her decision to accept help from Ben—a stranger—signifies the beginning of choosing self over certainty. The more time she spends in his company, the more she begins to shed the layers of her manufactured identity.

Her declarations, confessions, and confrontations with family are not just interpersonal moments but acts of reclamation. The transition is solidified in her symbolic burning of the “Good Girl” persona, a turning point where she redefines herself on her own terms.

Her growth is not linear but honest, messy, and raw. What emerges is a woman who is not wholly formed by the end, but one who is finally, truly, her own.

The Burden of Expectations

The narrative reveals how suffocating and damaging the weight of expectation can be—particularly when it is gendered and enforced through community and familial dynamics. Hope is raised to be dependable, sweet, and predictable.

Her twin sister Joy provides a useful contrast, acting as a foil who embodies rebellion and independence, while Hope conforms, absorbing the dreams her parents and fiancé envisioned for her. Even Roy, the man she is supposed to marry, views her not as a person but as a symbol of an ideal future: compliant, loyal, and comfortably ordinary.

The silent pressure to conform to that role intensifies the closer she gets to her wedding, until it snaps. But the story doesn’t stop at rebellion.

It scrutinizes the ways expectations operate even after one tries to escape. Hope constantly battles the internalized guilt of disappointing her family, the judgment of her town, and the fear of seeming irrational or unstable.

Her interactions with Joy, the townspeople, and especially Roy’s family show how those expectations mutate into coercion and subtle manipulation. Even her moments of assertiveness are initially tinged with uncertainty, showing how deeply embedded those obligations are.

However, as the narrative progresses, she learns that expectations are not obligations. They are illusions of duty that can be broken.

In confronting these illusions and embracing the discomfort that follows, she earns the right to choose a path ungoverned by others.

Healing Through Connection

The bond between Hope and Ben is not a standard romantic arc but a journey of mutual healing. Both characters are emotionally bruised—Hope by the stifling predictability of her former life, and Ben by the chaos and isolation of fame.

Their connection works not because they rescue each other, but because they offer one another space to be honest, broken, and safe. The intimacy they build is not rushed or romanticized.

It grows from small, human gestures: listening without judgment, respecting boundaries, and offering support without expectation. Hope’s journey toward healing is anchored by these interactions, where she is encouraged to speak the truths she had never voiced.

In return, Ben begins to reimagine himself not as a stage persona or broken artist, but as a man capable of gentleness and purpose. Even their sexual relationship is portrayed with emotional sensitivity, emphasizing trust and exploration over passion for its own sake.

The authenticity of their connection creates a sanctuary that allows them both to examine their pasts without fear. Through each other, they come to understand that love is not about fixing someone—it’s about witnessing them without trying to change who they are.

Their union by the end of the story is not a fairytale resolution but a choice rooted in mutual recognition and earned understanding.

The Courage to Confront the Past

In I Do With You, transformation is not just a forward-moving journey—it requires looking backward with honesty. Hope’s greatest growth moments often come not from new beginnings, but from facing the unresolved aspects of her past.

Her visit to her sister Joy, her confrontation with Roy, and even her public appearances in familiar spaces like Rosemary’s Diner or Chuck’s bar are acts of reclamation. These are places and people that once defined her, and she returns to them not as the girl they knew, but as someone trying to redefine her own terms.

The tension in these encounters is critical. They highlight the fragility of the new identity she’s trying to build, but also the strength it takes to bring that identity into spaces filled with expectation and judgment.

Her phone call with Roy is especially poignant—not because it’s a final goodbye to a romantic partner, but because it symbolizes the closing of a chapter that had entrapped her for too long. Even Ben must confront his own history, owning up to the secrecy around his fame and making a vulnerable public expression through music.

Healing, the novel suggests, is only possible when the past is no longer denied but faced head-on. It doesn’t mean the past vanishes, but rather that it no longer controls the narrative.

Reclaiming Female Desire and Agency

Hope’s evolving relationship with her own body, choices, and desires is a powerful undercurrent throughout the novel. Early in the story, her role as Roy’s future wife is deeply performative—expected to say the right things, wear the right dress, and smile on cue.

Her sexuality is subdued, molded by others’ expectations of innocence and submission. But her time with Ben offers something radically different: autonomy.

There is no rush or pressure, only invitations and choices. Her flirtation, her first experiences of genuine pleasure, and her bold decision to be physically affectionate in public are more than romantic acts—they are declarations of agency.

These scenes are crafted with emotional nuance, never stripping her of control. Even when she’s drunk, Ben’s respect for boundaries reinforces the idea that desire should always be consensual and self-driven.

By the time they make love, the moment is less about sex and more about reclaiming her right to pleasure on her own terms. The contrast with Roy—who is possessive and entitled—makes this even more powerful.

Hope’s journey becomes one of understanding that her body, her feelings, and her pleasure are not tools for validation or symbols of morality, but part of her own freedom.

Small-Town Dynamics and Resistance

Maple Creek is not just a backdrop in the novel—it is a character in itself, representing both suffocation and subtle rebellion. On the surface, it is the kind of town where gossip spreads quickly, traditions reign supreme, and loyalty is expected to fall along predictable lines.

Hope’s rebellion is, therefore, not a private act; it’s a public scandal. But what’s remarkable is how the town, in quiet and unexpected ways, begins to support her.

From Rosemary’s lie to the sheriff to the former teacher’s kind words, small gestures of support reveal an undercurrent of resistance within the town’s rigid structure. These moments challenge the binary of conformity versus defiance, showing that even within conservative environments, change is possible.

The town becomes a mirror, reflecting both the constraints that shaped Hope and the new community she might build. Even the hostile characters—like Brooklin or Roy—serve to sharpen Hope’s clarity about who she no longer wishes to be.

By the end, Maple Creek is no longer a prison but a battleground of transformation, where old roles are questioned and new identities are fought for, not just by Hope but by those who quietly cheer her on.