I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying Summary and Analysis

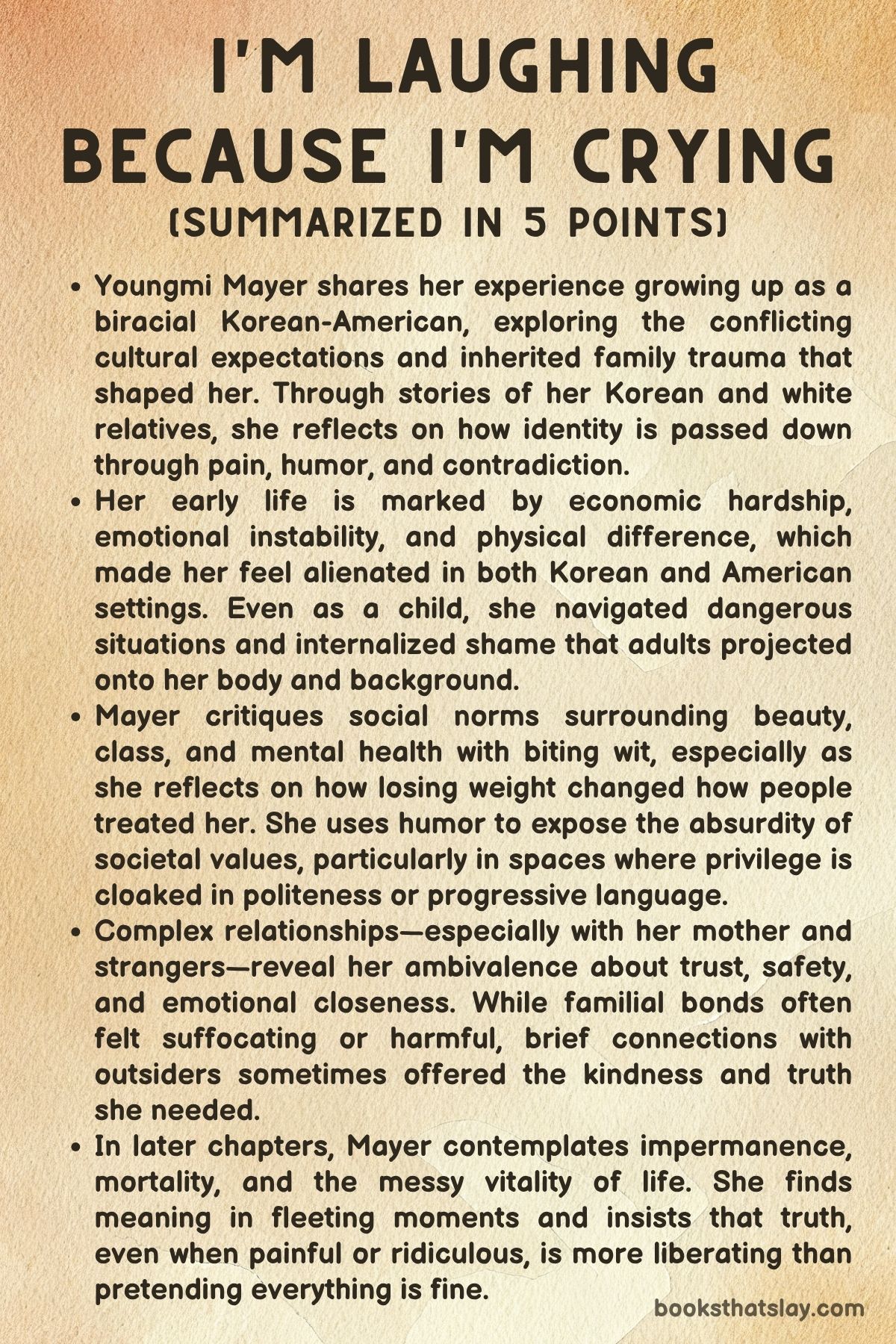

I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying by Youngmi Mayer is a raw, and sharply humorous memoir chronicling the author’s journey through generational trauma, racial identity, class struggle, and self-discovery. With her characteristic irreverence and vulnerability, Mayer paints a vivid picture of growing up as a biracial Korean-American woman navigating cultural alienation, abusive family dynamics, and societal neglect.

Her story is as much about surviving pain as it is about reclaiming power—through comedy, motherhood, and community. Mayer transforms personal chaos into a narrative of resistance and radical self-expression, offering readers an unfiltered look at what it means to survive, laugh, and speak truth in the face of erasure.

Summary

I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying opens with a brutally self-aware tone. Mayer questions her own worth as a narrator, framing herself as unremarkable and mentally unstable.

However, this deliberate act of self-deprecation becomes a defining strategy. She introduces the idea that exposing one’s failures and mental illness is not weakness but a form of liberation, particularly for marginalized individuals like Asian Americans who are often forced into stoicism and conformity.

Her unapologetic truth-telling and dark humor carve out a space where she can exist fully—flawed, angry, and painfully real.

The memoir first explores Mayer’s early childhood and family history, beginning with the trauma endured by previous generations. Her great-grandmother’s abduction and the forced marriage of her grandmother establish a lineage marred by violence and repression.

These inherited traumas manifest in Mayer’s parents: her father, raised by an abusive father in Jersey City, grows into a man defined by instability and neglect. He marries young, is later abandoned, and eventually drifts to Nairobi and then Alaska, where he meets Mayer’s mother.

Their union—haphazard and lacking emotional maturity—results in Mayer’s birth in Korea. Her parents are emotionally underdeveloped, unable to provide structure or care, and their dysfunction becomes Mayer’s formative environment.

Mayer’s early years in Korea are characterized by isolation and racial alienation. Born with jaundice, she is deemed unnatural by a religious doctor.

She grows up in Songtan, a seedy town surrounding a U. S.

military base, where Korean women in bars cater to American soldiers in an eerie, hyper-commercialized space. These women, dead-eyed and silent, remind Mayer of Hoho Ajumma—a ghostly figure from Korean folklore—and she perceives their avoidance as an act of supernatural protection.

Her mixed-race identity sets her apart in a rigidly conformist society. In Jeju-do, where she lives in near-parentless chaos, children roam unsupervised and form protective gangs.

Mayer survives through allegiance to these groups, but she also endures manipulation and abuse. She is not targeted out of cruelty, but as a result of children mimicking the damaged adults around them.

In Korea, Mayer is a “wangtta”—the child universally bullied—due to her mixed heritage and poverty. While her father revels in the attention his whiteness brings, Mayer is ostracized, attacked, and othered.

When she moves to Saipan, she gains social privilege due to her appearance but still struggles against toxic nationalism and classism from the Korean diaspora. She finds brief refuge in friendships and small acts of rebellion, even as she confronts the performative cruelty of adults, like a principal who maintains discipline through theatrical violence.

Throughout her childhood and adolescence, Mayer wrestles with abandonment, betrayal, and shame. Her half-sister plays a pivotal role in a traumatic episode where she calls the police and plants drugs to sabotage Mayer’s attempt to flee their chaotic home.

This betrayal reflects her sister’s own lifelong suffering and internalized trauma—another result of neglect, abuse, and systemic racism. Their mother, emotionally distant and envious of Mayer’s growing beauty, reinforces toxic ideas about femininity and value.

When Mayer tries to run away, it’s not just to escape the physical environment, but to seek the maternal love and validation she never received. Instead, she ends up at a CPS facility, where male staff members humiliate her, echoing a society that both fetishizes and reviles young women.

A significant moment comes when Mayer’s teacher accuses her of plagiarism. This unjust accusation robs her of her voice, symbolizing the broader theft of selfhood she experiences as a woman, a mixed-race child, and a victim of trauma.

Writing, a skill she inherits from her mythologizing father, becomes both weapon and shield. Denied permission to write, she turns to stand-up comedy as a form of defiance and healing.

The comedy stage, where she often fails in front of indifferent audiences, becomes sacred ground. Here, she tells her story on her own terms.

The memoir then follows Mayer into young adulthood and her immersion in Korean society once more—this time, as part of Seoul’s underground punk scene. She sharply contrasts the hyper-privileged Jaebol children with the scrappy punks and outcasts she associates with.

Korean society’s rigid hierarchy and obsession with appearances are revealed as suffocating, violent forces. Mayer’s experiences in Korea highlight class warfare, social absurdities, and the brutal cycles of abuse that tradition often hides.

When Mayer immigrates to the U. S., she doesn’t find safety or peace. Her life in San Francisco is marked by further instability—she shares apartments with meth users, survives rape, and endures poverty.

But she also finds fleeting joy. She marries in secret, gives birth to her son Mino, and co-founds Mission Chinese Food, a celebrated restaurant that becomes the backdrop for another personal transformation.

Her role in the restaurant eventually fades as she is pushed into domesticity, but her emotional awakening through motherhood gives her renewed purpose.

The breakdown of her marriage and the collapse of the restaurant reflect her internal unraveling. Depression, shame, and financial ruin follow.

Yet she begins again—through comedy, podcasting, and reclaiming her identity outside of motherhood and marriage. Dating post-divorce becomes another crucible: she experiences rejection, disappointment, and fleeting intimacy.

Her relationships with women add depth to her understanding of herself, and she ultimately accepts that she has always been her own protector.

As the COVID-19 pandemic isolates the world, Mayer turns inward, exploring themes of loss and survival through a lens sharpened by grief and absurdity. Her relationship with Danny, her ex-husband, finds a strange détente, and his praise on her podcast becomes a rare acknowledgment of her worth.

Through all of this, motherhood grounds her. Breastfeeding—brutal and primal—links her to generations of women who endured for the sake of their children.

Her love for Mino is fierce and transformative, eclipsing all previous definitions of fear or failure.

In its final chapters, I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying becomes a manifesto of resilience. Mayer embraces failure not as something to overcome, but as proof of life.

Her radical honesty, her refusal to be silenced or erased, becomes a form of generational healing. She doesn’t promise triumph, but she offers something better: the courage to laugh, cry, and live in painful truth.

Key People

Youngmi Mayer

The heart of I’m Laughing Because Im Crying beats within the raw, uncompromising voice of Youngmi Mayer, who serves as both narrator and central character. Her portrayal is fiercely complex: a survivor of intergenerational trauma, a cultural outsider, a reluctant maternal figure, and a comedian who finds her voice in the very spaces where silence once reigned.

Mayer emerges not just as a product of dysfunction but also as a radical revisionist of it. She wrestles openly with feelings of inadequacy and unworthiness, weaponizing her vulnerability through comedy.

Her mental illness, sense of displacement, and chaotic upbringing aren’t buried—they are paraded out as proof of life and resilience. What makes Mayer especially compelling is her refusal to conform, either to the submissive, invisible ideal often projected onto Asian women or to Western ideals of coherent upward mobility.

Instead, she drifts, adapts, collapses, and reforms, always refusing to be erased. Her survival is less about triumph than defiance—against invisibility, patriarchy, classism, and inherited pain.

Ultimately, she is both a wounded child and a sharp-eyed adult, simultaneously reclaiming her past and reimagining her future.

The Father

Mayer’s father is portrayed as a profoundly broken man whose own abuse and neglect render him emotionally stunted and incapable of sustaining stable relationships. His life is marked by chaos and transience, moving from Jersey City to Nairobi and finally to Korea, driven not by purpose but by escapism.

He is shown to lack both emotional and parental maturity, often forcing his daughter to step into the adult role. Despite flashes of eccentricity and charisma, he is fundamentally unreliable and selfish.

Yet Mayer doesn’t flatten him into a villain. Instead, she places his shortcomings in the context of generational trauma, particularly that inflicted by his own father.

This approach underscores a central theme: that people can be victims and perpetrators at once. The father remains an emotionally absent figure who casts a long shadow, more symbol than source of support, and his legacy is one of fragmentation and silence that Mayer must eventually choose to break.

The Mother

Mayer’s mother is a paradoxical figure—simultaneously protective and envious, emotionally distant yet foundational to Mayer’s understanding of female repression and sacrifice. She is a woman burdened by the expectations of Korean womanhood and the failures of her own dreams.

Her behavior often veers into coldness and competition, especially as Mayer matures into a beautiful young woman. Rather than nurturing her daughter’s identity, she reacts with withdrawal and jealousy, reproducing the cultural misogyny that equates a woman’s worth with youth and desirability.

Yet her mother’s suffering is palpable, filtered through prophetic dreams and the weight of a life surrendered to survival. Mayer recognizes in her mother the echoes of her grandmother—another woman who buried her pain beneath mockery and bitterness.

Despite their conflicts, Mayer’s mother functions as a crucial node in the matrilineal web of inherited trauma, shaping Mayer’s eventual decision to speak rather than be silenced.

The Half-Sister

The half-sister occupies a tragic role in the memoir, emblematic of a life warped by neglect, illness, and social erasure. Her betrayal—planting drugs on Mayer and calling the police—is devastating, yet it is not depicted as an act of villainy but as the inevitable product of lifelong pain and abandonment.

Mayer excavates her sister’s suffering with care, detailing how medical conditions, immigration struggles, and familial indifference have conspired to dehumanize her. The sister, like Mayer, is shaped by forces far beyond her control, and her harmful actions are not devoid of context.

Her character becomes a painful reminder that in environments of systemic neglect and trauma, love often mutates into sabotage. Mayer’s analysis of her sister is an exercise in reluctant compassion—acknowledging her harm without denying her humanity.

Danny

Danny, Mayer’s ex-husband and business partner at Mission Chinese Food, serves as both a catalyst and foil in the memoir’s latter chapters. Initially united by love and shared ambition, their paths diverge as Danny climbs the ladder of culinary celebrity while Mayer becomes a sidelined domestic figure.

He represents the seductive allure of class mobility and institutional success, but also the betrayals embedded within them. Mayer contrasts her alignment with the restaurant’s workers—often poor and exploited—with Danny’s alignment with investors and power brokers.

Though not malicious, Danny is emblematic of someone who has adapted seamlessly into elite spaces, shedding his former identity without reckoning with the human cost. Their relationship’s arc—from collaboration to estrangement—mirrors Mayer’s own ideological journey from complicity to confrontation.

Yet even in their parting, there is complexity. Danny’s final act of praise on her podcast suggests a flicker of recognition, a brief moment of mutual dignity within the wreckage.

Mino (the Son)

Mino, Mayer’s son, emerges as a grounding presence amid the chaos and pain that dominate the memoir. While he is not heavily characterized in terms of dialogue or direct action, his symbolic weight is immense.

Through him, Mayer begins to reevaluate her worth, initially through the flawed lens of his perceived innocence and value. Her experiences of motherhood—particularly the raw, physical struggle of breastfeeding—connect her to a lineage of maternal suffering and strength.

Mino becomes a mirror through which Mayer sees her own capacity to nurture and protect, qualities denied to her in her own childhood. He is both a source of purpose and a reminder of what is at stake.

In loving Mino, Mayer learns to hold herself with more tenderness. His presence catalyzes her transformation from a fragmented survivor to a fierce protector and storyteller, affirming that healing, while incomplete, is possible.

The Korean Bar Women

Though unnamed and spectral, the Korean bar women who populate Mayer’s childhood memories are among the most haunting characters in I’m Laughing Because Im Crying. Existing in the margins of U.S. military towns, these women are seen through the eyes of a mixed-race child searching for recognition.

Their averted gazes and deadened expressions signal a shared history of abandonment and exploitation. Mayer mythologizes them as Hoho Ajumma figures—ghosts who cannot acknowledge their children without endangering them.

They embody the shame and silence imposed on women who exist outside social respectability, yet they also serve as spiritual ancestors to Mayer’s own rebellion. In their refusal to look, they paradoxically offer a kind of protection, warning her of the dangers she will later confront.

Their presence lingers throughout the memoir as a testament to the unseen women who shaped her world.

The Principal and Authority Figures

Figures of institutional authority—teachers, principals, male caregivers—appear throughout the memoir not as protectors but as perpetrators of humiliation, control, and dehumanization. The school principal in Saipan wields a theatrical paddle to enforce fear rather than discipline.

Florida Santa, the teacher who accuses Mayer of plagiarism, steals her creative identity and sparks a prolonged crisis of self-worth. Male social workers at CPS facilities leer and condescend rather than care.

These figures are less individualized than archetypal, representing the larger systems that devalue and pathologize girls, especially those of color. Their repeated failures contribute to Mayer’s growing disillusionment with traditional forms of power and underscore her eventual turn to comedy as a space of genuine agency and expression.

In totality, the characters of I’m Laughing Because Im Crying form a deeply interconnected mosaic of inherited pain, systemic failure, and hard-earned voice. Each one reflects an aspect of the narrator’s psyche, history, or future—and together they animate a memoir that refuses sentimentality in favor of searing, transformative honesty.

Analysis of Themes

Radical Vulnerability as Resistance

Youngmi Mayer’s memoir I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying finds its most persistent emotional force in the act of radical vulnerability, not as a performance but as a weaponized tool of survival and resistance. Rather than shying away from labels like “loser” or “dumbass,” the narrator embraces these terms, stripping them of their power to shame.

This isn’t self-deprecation for comedic effect—it is an assertion of truth in a world that demands polish, poise, and performative strength, especially from Asian American women. In this context, mental illness, failure, and shame are not private disgraces but public realities that demand to be named and laughed at with defiance.

Mayer’s confessions become a form of cultural disruption. In a community often pressured into stoicism and exceptionalism, her openness punctures myths about respectability and success, redefining the very boundaries of identity and strength.

By embracing her perceived deficiencies, Mayer offers a counter-narrative to mainstream representation, particularly the model minority myth. She reclaims space for Asian Americans—especially those born outside the Western gaze—who do not, and will not, fit sanitized templates of success or palatable representation.

Her openness about being “fucking nuts” reframes emotional chaos as authentic expression, not pathology. It also becomes a generative space where others, especially readers who carry their own private shames, may finally feel seen.

The laughter she elicits is not just entertainment; it is catharsis. The emotional nakedness becomes an invitation, a protest, and a declaration that flawed existence, especially one born of systemic erasure, is not just enough—it is worthy of attention, of narrative, and of care.

Intergenerational Trauma and Behavioral Inheritance

The stories Mayer tells of her ancestors are not decorative background—they are constitutive of the memoir’s present. Trauma is not presented as isolated or situational; it is patterned, cyclical, and genetically embedded.

The abduction of her great-grandmother, her grandfather’s abuse, her grandmother’s forced marriage—these are not merely family anecdotes but manifestations of cultural, colonial, and gendered violence, transmitted through behavior and silence across time. Mayer’s metaphor comparing this inherited pain to motifs in Back to the Future offers a darkly humorous, yet accurate, insight: the past lives again in the habits and choices of the present, often unconsciously.

What makes Mayer’s exploration so incisive is that she does not cast blame in a linear way. Her father, emotionally frozen and erratic, is simultaneously a victim of cruelty and a perpetuator of chaos.

Her mother’s jealousy and cruelty are likewise framed not only as personal failings but as the outcomes of gendered conditioning and cultural pressures. The memoir recognizes how survival tactics often look like dysfunction—how emotional coldness, secrecy, or bitterness may actually be forms of self-preservation.

The narrator’s own suffering becomes a reiteration of this generational script. But by naming these behaviors, by articulating their roots and effects, Mayer breaks the loop, at least partially.

Her writing becomes a means of refusing both the silence of her foremothers and the apathy of her father. In her hands, the story is no longer a repetition—it is a reckoning.

Cultural Displacement and Biracial Alienation

Mayer’s biracial identity is never incidental in I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying; it is a primary lens through which her experiences of abandonment, fetishization, and alienation unfold. Born in Korea to a white American father and a Korean mother, Mayer inhabits an existence that is racially marked no matter where she goes.

In Korea, she is honhyul—a child of mixed blood—stigmatized and othered by a society obsessed with racial purity and conformity. Her bodily difference becomes a site of bureaucratic erasure and social abuse.

Children mimic adults’ prejudices, and Mayer is punished not just by peers but by institutions that deny her legitimacy.

When she moves to Saipan, her mixed-race appearance is ironically a source of privilege in a new colonial hierarchy. Yet this shift does not alleviate the core pain of displacement; it only reveals the fluid absurdity of racial and cultural power.

Wherever she is, her body is either exoticized or punished, never truly allowed neutrality or belonging. Her father’s whiteness, far from shielding her, becomes a beacon that draws both fetishizing attention and cruel exclusion.

The horror of being racially visible yet socially invisible is made vivid through her descriptions of ghost-like Korean bar women who avoid eye contact, sensing the danger of acknowledging children like her.

This persistent in-betweenness is not resolved but endured. Mayer’s humor and sharp observation allow her to turn this dislocation into insight.

Her identity is not neatly hybrid—it is fractured, messy, and deeply wounded, and that acknowledgment is its own form of truth-telling. Rather than seeking assimilation, she claims her ambiguity as the core of her reality, rejecting the demand to fit any singular mold.

Abuse, Survival, and Childhood as War Zone

Mayer’s memoir reframes childhood not as a protected phase but as a battleground, where children inherit and reenact the damage of broken adults. In her case, both parents are emotionally immature and incapable of caregiving.

The absence of structure, food, protection, or affection forces Mayer into the role of a reluctant adult, even as she remains a child. This reversal is not only a personal tragedy but also a social indictment—of how poverty, racism, and generational trauma conspire to destroy the possibility of innocence.

Her experiences in Jeju-do, where children govern themselves, dramatize the consequences of a world devoid of adult responsibility. Within this anarchic space, even cruelty becomes normalized.

Mayer recounts manipulation and sexual exploitation not as acts of sadism but as the byproducts of mimicry—children performing the scripts handed down to them. The boundaries between protection and predation blur, and the narrator survives not because she is rescued but because she learns to read danger and form fragile alliances.

Her friendships, though sometimes toxic, become makeshift families—sites of mutual understanding in a chaotic landscape.

Survival is not romanticized. It is dirty, painful, and often shameful.

Mayer’s descriptions avoid sensationalism; instead, they highlight how systemic abandonment leaves children to piece together meaning and safety from whatever is available. Her eventual turn to humor, then, is not a deflection but a strategy—one developed in an ecosystem where clarity, power, and justice were in short supply.

Her story makes clear that survival itself is an act of ingenuity, and that childhood, in such contexts, is less about growth and more about enduring.

Patriarchy, Femininity, and Motherhood

Throughout I’m Laughing Because I’m Crying, Mayer interrogates how femininity is shaped and distorted by patriarchy. From the bar women in Korea to her own mother’s withdrawal once she begins to “blossom,” Mayer traces how female bodies become battlegrounds of envy, desire, control, and projection.

Her mother’s inability to love her once she becomes visibly female suggests a cultural framework where women are taught to compete for male validation. This competition turns maternal love into conditional affection, making intimacy a site of constant negotiation and pain.

Her later reflections on breastfeeding and motherhood illuminate how the female body, even in its most nurturing form, is subject to physical torment and mythologized expectations. The act of breastfeeding is portrayed not as sentimental but as a violent, painful, and raw experience that connects her not just to other mothers, but to a lineage of women who suffered silently.

The primal nature of motherhood contrasts sharply with societal ideals of selfless grace and feminine passivity. Through this lens, Mayer exposes how women are asked to disappear into roles, whether mother, daughter, or wife, and how resistance often takes the form of quiet rage or mutiny.

Her exploration of dating post-divorce, including relationships with women, adds another dimension. By shedding the belief that she needs male attention to feel worthy, she begins to reconfigure power and care.

Her realization that she has always been the “protector” in her relationships recasts femininity not as passivity but as strength—often unacknowledged, always essential. Mayer’s femininity is not one of ideals but of survival, confrontation, and clarity, rooted in physicality and emotional intelligence.

Class Tension and Disillusionment with Success

The trajectory of Mayer’s involvement in Mission Chinese Food reveals how class operates not just economically but emotionally and ideologically. She begins aligned with the kitchen staff, viewing herself as part of the working class.

As her partner Danny rises in fame and wealth, accumulating luxury goods and industry clout, she is pushed into a role that resembles trophy wife more than partner. The restaurant’s collapse, catalyzed by internal conflict and labor exploitation, mirrors her own disintegration—emotionally, financially, and relationally.

The narrative complicates the idea of success. Mayer’s proximity to elite dining, designer fashion, and industry fame does not confer happiness or legitimacy.

Instead, it accelerates her alienation. Even as she helps build something iconic, her voice is gradually silenced.

Her disengagement from the business parallels her emotional withdrawal from a version of life she never aspired to. Her “firing” from the restaurant is not just a professional event but a symbolic death—a moment that confirms how systems prioritize status over solidarity.

Yet from this disillusionment comes a new form of creativity. Stand-up comedy, with all its humiliations and uncertainties, offers her an arena free of hierarchy.

The failures are hers alone, and so are the fleeting moments of success. Her post-Mission journey underscores a truth rarely stated: the end of a dream is not always a tragedy.

Sometimes, it is the beginning of something less glamorous but more honest. Her transformation from restaurateur’s wife to working comic is not framed as redemption but as release—from pretense, from ambition, and from the need to be anything but fully, unapologetically herself.