Snow Drowned Summary, Characters and Themes | Jennifer D. Lyle

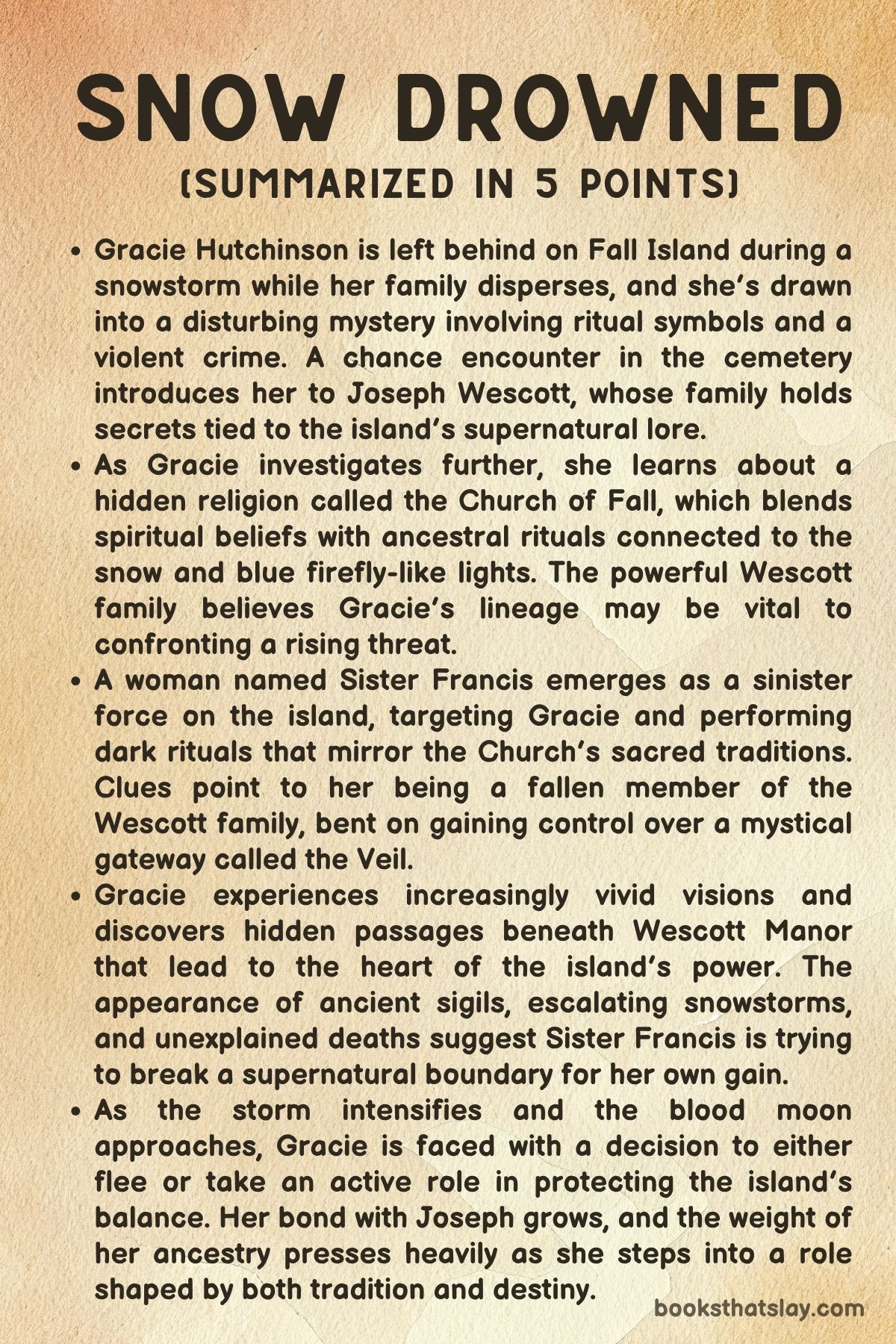

Snow Drowned by Jennifer D. Lyle is a chilling gothic horror novel set on the snowbound, insular Fall Island, where superstition, trauma, and ancient religious rituals blur the boundaries between reality and nightmare.

At its heart is Grace Hutchinson, a teenager whose rebellious nature clashes with the suffocating traditions of her home. When a blizzard isolates the island, Grace is forced into a terrifying journey of discovery involving a gruesome murder, a long-missing girl, and a cultic church that demands blood. As she uncovers her family’s role in an unholy tradition, Grace must fight not only for her survival, but to stop a monstrous power from rising again.

Summary

Grace “Gracie” Hutchinson has always felt like an outsider on Fall Island, a snowbound place where winters breed not only cabin fever but terrifying legends. Ten years before, a young girl named Jenna Grodonsky vanished during a Nor’easter, her disappearance linked to the island’s superstitions about snow and the eerie phenomenon of the “fairy lights.”

Now seventeen and desperate to escape both the island and the shadow of her older sister, Gracie finds herself stuck as another fierce storm approaches. While delivering flowers to her grandmother’s grave—a local tradition—she encounters Sister Francis, an unnerving nun her family always warned her about.

Their conversation is unsettling, especially as Sister Francis speaks cryptically about Gracie’s hands and the dangers of being alone.

In the cemetery, Gracie unexpectedly runs into Joseph Wescott, a popular, charismatic boy from the wealthy and religious Wescott family. Their reunion takes a dark turn when they discover that their family crypt has been desecrated.

Inside are the ritualistically arranged remains of three mutilated sheep and a shirtless, eyeless man, marked with strange carvings. The discovery shocks both teens, and while Joseph alerts the authorities, Gracie secretly takes photos.

Sheriff Rick, Gracie’s uncle, identifies the dead man as a homeless laborer from the mainland. Joseph raises the possibility that Sister Francis could be involved, but Rick dismisses it.

Nevertheless, Gracie’s fear grows.

Left alone at home, Gracie begins to piece together clues. A terrifying dream hints at something unnatural beneath the island’s snow.

Her online searches reveal that Jenna Grodonsky wasn’t the only one to vanish during snowstorms—more than a hundred names surface, all linked to snow and the fairy lights. The dread deepens when Sister Francis reappears, igniting a flaming sigil on Gracie’s lawn.

Gracie rushes inside to find her Aunt Judy unconscious. A mysterious object brands her palm with a sigil connected to her family.

Uncle Rick arrives soon after and deems it too dangerous for Gracie and Judy to stay at home. They are brought to Wescott Manor, where Joseph’s family lives in a grand, old-world estate steeped in tradition and mystery.

At Wescott Manor, Gracie is welcomed by Marin, the stern matriarch, and Samantha, her more grounded sister. The house runs on gas lamps and old customs, with deep ties to the Church of Fall, the island’s religious order.

Gracie begins to notice that the symbols on gravestones and bodies aren’t just ornamental—they’re connected to death and family legacy. The Wescotts, despite their luxurious setting, are devotees of the same lore that haunts Gracie’s memories.

Joseph becomes a rare comfort in this confusing environment. Though still unsure of his role, Gracie trusts him more than anyone else.

Together, they start digging deeper into the meaning of the sigils and the history of the Church of Fall.

Gracie discovers a diary hidden in the manor that belonged to Arlene Brimley, a young woman from generations past. Arlene’s journal reveals the dark secrets of the island: the Church of Fall is not a benign institution, but a cult demanding sacrifice.

Arlene’s sister, Maria, was promised to Ephraim Wescott, but was later murdered by their mother as part of a ritual. Arlene, devastated, ultimately became Sister Francis, dedicating her life to destroying the institution that ruined hers.

Through Arlene’s words, Gracie realizes that she has been marked for sacrifice, just as Maria was. Her sigil is a sign she’s been chosen.

Even worse, her own family—including her mother, whom she believed to be away on the mainland—is complicit in the cult’s plans.

Gracie’s escape attempt during a blizzard fails when she’s recaptured by her family. She learns more about Aaron Seville, the man in the mausoleum, who tried to flee the Church but was ultimately killed and sacrificed.

The marks on his body match the symbols Gracie has been researching, proving his death was part of the same ritual tradition. Her horror peaks when she meets Ephraim Wescott himself, now an elderly, mute man hidden in a greenhouse.

He tries to warn her that something about her selection is premature, suggesting there may be a flaw in the ritual.

She is dragged to the church’s sacred chamber, where a ceremonial dinner precedes the sacrifice. Gracie is washed, dressed, and presented like a lamb to be slaughtered.

Her blood is collected and offered to Marin Wescott. But thanks to a subtle act of rebellion from her mother—who gives her a sharpened rock—Gracie is able to carve out the sigil from her palm, invalidating her as an offering.

When the ritual proceeds anyway, the monstrous being summoned from beneath the island recognizes the missing mark. In a terrifying twist, Gracie marks Samantha instead.

The creature consumes her, sparking panic among the congregation.

The church collapses as the creature devours its worshippers. Joseph, shattered by his family’s destruction, turns on Gracie and tries to kill her to finish the ritual.

But he is taken by the fairy lights, leaving Gracie, Judy, and her mother to flee the collapsing mountain. They escape to Florida, but peace remains elusive.

Gracie is haunted by visions and the realization that the cult has not ended. Her wounds are healing unnaturally, and she receives an indestructible copy of The Book of Fall.

It becomes clear that the evil they tried to destroy has only transformed.

The story closes with a new resolve. Gracie and her mother, emotionally scarred but bonded by truth, plan to infiltrate the cult’s new form—this time operating aboard a cruise ship—and destroy it from within.

The ending suggests that though Fall Island has fallen, the Church of Fall has merely adapted. The monster still demands sacrifice.

And this time, Gracie will make sure it pays dearly.

Characters

Grace “Gracie” Hutchinson

Gracie serves as the fierce and emotionally raw protagonist of Snow Drowned, evolving from a sardonic, disillusioned teenager into a hardened survivor. Initially presented as the black sheep of her family, Gracie’s restlessness and cynicism mask a profound loneliness and emotional depth.

Her relationship with her mother is strained, and she finds solace only in sarcastic detachment and a desire to escape Fall Island. This longing for freedom collides tragically with the horrifying discoveries she stumbles upon—ritual murders, supernatural lore, and a chilling familial betrayal.

As the narrative progresses, Gracie becomes the unwilling center of an ancient sacrificial rite, marked by a literal sigil branded into her flesh. Her character’s trajectory is one of disillusionment and reluctant heroism.

She peels back generations of lies, betrayal, and cultic control, only to discover that her own bloodline is complicit. What makes Gracie compelling is her emotional complexity—her horror, anger, and grief are as prominent as her courage.

She’s not a fearless heroine but a real, broken girl whose defiance becomes her salvation. Even after surviving the monstrous ritual and fleeing the collapsing island, Gracie remains haunted by the past and physically altered by it.

Her final transformation—choosing to fight back against the cult’s resurgence—cements her as a character driven not by hope, but by sheer will and a fierce desire for justice.

Jenna Grodonsky

Though her disappearance occurs early in the narrative, Jenna’s character haunts Snow Drowned as a lingering trauma and mystery. Her childhood terror of snow, born from a cruel prank involving a snow tunnel, catalyzes her phobias and sets the tone for the novel’s chilling atmosphere.

Jenna’s life becomes increasingly isolated, her fear of winter morphing into a metaphor for psychological paralysis and inherited trauma. Her vanishing during a fierce Nor’easter becomes a legend on the island, a symbol of Fall Island’s tendency to swallow its victims whole.

More than a character, Jenna represents the first tremor of the darkness the island hides. Her legacy lives on in Gracie’s fear and determination, and her fate—never fully resolved—suggests the quiet, cumulative toll the cult’s influence has had on the island’s youth.

Jenna’s character is a ghostly reminder that many do not escape, and that the line between myth and truth is dangerously thin on Fall Island.

Joseph Wescott

Joseph Wescott emerges as a surprising and layered character whose charm conceals a burdened conscience. As the scion of the Wescott family—religious and social royalty on Fall Island—Joseph initially appears to be a golden boy with a streak of rebellion.

He offers Gracie companionship and refuge, and his initial acts of kindness, like calling the authorities after the graveyard discovery, set him up as a trustworthy ally. Yet his journey is rife with internal conflict.

Torn between familial loyalty and growing revulsion toward the cult’s practices, Joseph embodies the moral ambiguity that defines much of Snow Drowned. His desire to escape is as strong as Gracie’s, but his complicity in the rituals, even if unintentional, weighs heavily on him.

By the novel’s end, Joseph is emotionally shattered, his mental stability fractured by grief, guilt, and betrayal. His attempt to murder Gracie in a last-ditch effort to fulfill the ritual underscores his descent from ally to threat.

Still, his earlier defiance and protection of Gracie suggest a man at war with himself—capable of love but enslaved by legacy.

Sister Francis (Arlene Brimley)

Sister Francis is one of the most enigmatic and unsettling characters in Snow Drowned, bridging past and present horrors through her tragic backstory. Originally Arlene Brimley, she was a devout young woman swept up in the church’s promise and familial pride.

Her transformation into Sister Francis is marked by disillusionment and vengeance after witnessing the horrific murder of her sister Maria at the hands of their mother, and enduring her own brush with death. From then on, she becomes a spectral presence on the island—a relic of a forgotten war against the cult.

Though many view her as dangerous or mad, Sister Francis is, in truth, a martyr-like figure whose rage is righteous. Her cryptic warnings and eerie behavior are expressions of a life consumed by the need to expose and destroy the cult.

Her death—ritually executed to appease the god beneath the island—feels both cruel and tragically fitting. In the end, she is both a victim of the system she once believed in and a rebel who refused to be silenced.

Marin Wescott

Marin Wescott is the spiritual and ideological leader of the Church of Fall, a chilling embodiment of generational fanaticism and ruthless control. Her regal demeanor, cloaked in religious authority and ancestral privilege, masks a monstrous will to dominate and sacrifice others in the name of a forgotten god.

Marin’s manipulation of tradition, her orchestration of blood rituals, and her willingness to exploit her own family make her the novel’s central antagonist. Yet she is no caricature of evil—Marin believes in her divine mission, sees sacrifice as sacred, and considers herself a protector of Fall Island’s fate.

Her authority is rooted in performance and myth, as evidenced by the grandeur of the ceremonies and her grip on followers. Marin represents the kind of institutional evil that survives through secrecy and reverence.

Her downfall, at the hands of the very forces she hoped to control, is poetic justice—a tyrant devoured by the god she sought to appease.

Jessica Hutchinson

Gracie’s mother, Jessica, is a deeply conflicted character whose betrayal is among the story’s most emotionally devastating twists. At first presented as a stern and somewhat neglectful parent, Jessica is eventually revealed to be deeply enmeshed in the cult’s inner workings.

Her return to the island, secretive behavior, and eventual participation in Gracie’s ritual preparation mark her as a traitor. Yet Jessica is not wholly evil; she shows flickers of remorse and ultimately aids her daughter’s escape by concealing a rock in her bandages—a small act of rebellion with massive consequences.

Jessica’s role illustrates the psychological entrapment of generational loyalty. Raised within the church’s rigid doctrine, she is unable to fully reject it, even as she watches her daughter suffer.

Her post-escape state—emotionally numb and spiritually broken—suggests a woman forever damaged by her complicity. She survives, but at the cost of her identity, now bound to the mission of dismantling the cult from within alongside her daughter.

Samantha Wescott

Samantha, Marin’s sister and fellow cult leader, plays a quieter but equally sinister role in Snow Drowned. While Marin commands with fire and fervor, Samantha operates in the shadows, aiding in the logistical and spiritual maintenance of the rituals.

She exudes a maternal warmth that is disarming, which makes her betrayal even more chilling. Samantha’s participation in the final ceremony, including the preparations of the dead and the anointing of the chosen, places her firmly within the inner circle of the cult’s horror.

Her end—being marked as the new sacrifice and devoured by the summoned god—is a grim but fitting resolution. Samantha, like many others in the Wescott family, represents the institutional complicity that allows evil to thrive.

Her demise serves as both punishment and symbol: the old guard consumed by the very darkness it fed.

Stubby

Though a supporting character, Stubby offers moments of rare humanity and courage within the bleak landscape of Snow Drowned. Loyal and brave, he stands by Gracie and Jessica during the final escape, risking his life to help them flee the collapsing church.

Stubby is not a warrior or a scholar, but his unwavering commitment and physical protection make him indispensable in the story’s climax. His presence reaffirms the possibility of moral clarity amidst chaos and deception.

In a world overrun by betrayal, Stubby’s loyalty shines as a rare, comforting constant. He survives the collapse, one of the few men of action who does so with dignity intact.

Ephraim Wescott

Ephraim, once a romantic figure in Arlene Brimley’s life, is discovered as a shell of his former self—mute, paralyzed, and hidden away in a greenhouse like a relic. His presence is a sobering testament to the toll the cult has taken even on its former leaders.

His attempt to warn Gracie, albeit limited, reveals that he remains mentally aware and deeply opposed to the direction the cult has taken. Ephraim’s character is tragic, a man trapped not only by his body but by his legacy.

He functions as a symbol of the lost humanity within the Wescott line, a reminder that not all who serve the church do so willingly or without consequence. His cryptic warning—“too soon”—introduces the idea that the sacrificial system is not as invincible as it seems, and that error can become revolution.

Themes

Generational Trauma and Betrayal

In Snow Drowned, the narrative is propelled by the destructive power of generational trauma, manifested through both familial betrayal and inherited roles in the island’s secretive cult. Grace’s journey becomes a slow revelation that her family is not only complicit in horrific acts but has, for generations, played an integral part in maintaining a system of sacrificial violence disguised as religious devotion.

This trauma begins with the historical account of Arlene Brimley, a young woman whose dreams and beliefs are crushed by the brutal death of her sister and her own transformation into Sister Francis. The pain Arlene experiences is cyclical, perpetuated through secrecy and silence rather than healing.

Grace’s own mother continues this legacy by deceiving her daughter, actively participating in her grooming for ritualistic death under the guise of ancestral duty. The betrayal feels intimate and chilling because it emerges from those meant to protect and nurture.

This cyclical harm—the passing down of obligation, belief, and silence—is presented not as a relic of the past but as a living force that manipulates and consumes. Grace’s struggle to break free is not just physical but psychological, as she must untangle herself from emotional loyalty to people who are complicit in her destruction.

The theme emphasizes how systems of power and belief rooted in the family can be even more insidious than those imposed externally, because they are accepted as love and tradition. Breaking from them requires an almost mythic act of defiance, which Grace ultimately undertakes, shattering the chain of violence with her refusal to be sacrificed.

Isolation and Claustrophobia

The psychological and physical isolation on Fall Island operates as more than just a setting; it is a suffocating force that shapes and traps every character in Snow Drowned, particularly the women. Jenna’s chionophobia, born from a childhood trauma where she was buried in a snow tunnel by her cousins, acts as a haunting metaphor for the way trauma freezes a person in place, encasing them in fear.

Her disappearance in a blizzard becomes both literal and symbolic: she is consumed by the very thing she fears, leaving behind a vacuum of uncertainty and dread. Similarly, Gracie’s experience is marked by the sensation of being watched, cornered, and manipulated within enclosed spaces—the manor, the church, her own home.

Snow, which might traditionally be associated with serenity, becomes a weapon of entrapment. The seasonal blizzards are like sentient barriers, ensuring that no one can leave, enforcing submission to the island’s ancient, brutal customs.

Even technology and outside intervention are rendered useless. The geographic isolation reinforces the islanders’ psychological imprisonment within their traditions, superstitions, and lies.

This claustrophobic atmosphere compounds as Gracie uncovers layer after layer of betrayal, increasingly unable to trust even the people closest to her. The fear isn’t just of being physically trapped but of having no emotional or ethical way out.

The oppressive geography reflects the characters’ emotional stasis, their inability to escape what has always been and what is expected of them. The novel uses snow not as a passive element but as a malevolent force, binding victims to the land and to the fate it demands.

Female Exploitation and Objectification

Snow Drowned presents a deeply unsettling portrait of how women are historically and ritualistically objectified, valued not as autonomous individuals but as vessels for sacrificial power. Grace’s journey from an average teenage girl to a marked offering is chilling in how it mirrors historical patterns of religious and cultural systems scapegoating and controlling female bodies.

The Church of Fall, the cult operating on the island, thrives on the offering of women, treating them as symbols of purity and vessels of divine appeasement. From Maria’s gruesome murder by her own mother to Arlene’s transformation into a figure of wrath, and eventually to Grace being paraded in a ceremonial gown, every stage of womanhood is co-opted into a system that demands beauty, silence, and compliance.

Grace’s body is literally marked—branded—signifying her status not as a person but as a commodity. Even her pain and resistance are folded into the cult’s narrative of necessary suffering.

The narrative doesn’t offer easy redemption; rather, it focuses on Grace’s decision to reclaim her agency through self-mutilation, a shocking but necessary act to invalidate her “purity” in the eyes of the cult. Her refusal to play the role assigned to her destabilizes the ritual system, revealing that power can be reclaimed in moments of radical defiance.

The theme underlines the historical resonance of how female identity is often shaped and suppressed by religious and cultural machinery, while also offering a brutal yet empowering vision of resistance.

The Corruption of Faith

The religious institution at the center of Snow Drowned is not simply misguided—it is fundamentally rotten, a cult that has warped centuries of tradition into a justification for murder. Faith, which might offer comfort or meaning in times of suffering, becomes a tool for control and violence.

Marin Wescott’s sermons, the sacred rituals, and the reverence for “fairy lights” mask horrifying practices rooted in blood sacrifice and deception. The Book of Fall, with its encrypted sigils and ancient commands, is treated with the reverence typically reserved for holy texts, but its teachings are grotesque and violent.

What makes the corruption more insidious is that it is not enforced through brute strength alone but through love, family, and heritage. Believers aren’t outsiders—they are kin, neighbors, and respected elders.

This perversion of faith creates a sense of dissonance for characters like Grace and Joseph, who begin by trusting their communities and end up having to reject them entirely to survive. Even Sister Francis, who becomes an antagonist of sorts, is also a victim—an example of a believer turned rebel, twisted by the horrors she once supported.

The novel suggests that the most dangerous lies are those told in the name of salvation, and the most damaging rituals are those passed down as sacred truths. This theme examines how faith can be corrupted when obedience is valued over morality and when tradition masks exploitation.

It forces readers to question the true nature of devotion and whether loyalty to inherited beliefs can ever justify cruelty.

Survival and Moral Resistance

Throughout Snow Drowned, the notion of survival is entangled with ethical compromise, making it a question not just of endurance but of conscience. Grace is not merely trying to stay alive; she is battling to retain her sense of self and integrity in the face of a monstrous system that seeks to erase both.

At every turn, she is forced to make decisions that test her resolve and clarity—whether to trust Joseph, whether to act against her mother, whether to mutilate herself to invalidate a sacrifice, or whether to condemn another in order to escape. These are not decisions made in comfort or safety but under crushing pressure, where the stakes are both physical and spiritual.

Grace’s moral compass evolves as she realizes that survival without resistance would be hollow—that to live while complying with the cult would make her complicit in its horror. The decision to transfer the sacrificial mark to Samantha, for instance, is not born of cruelty but of necessity; Grace must choose between her own life and the perpetuation of a violent system.

This theme also applies to Jessica, her mother, who undergoes her own arc of awakening and resistance, albeit more ambiguously. By the novel’s end, the characters who survive are not just those who escaped the ritual but those who were willing to risk everything to stop its cycle.

This underscores that true survival in such a context requires defiance, a refusal to be shaped by the darkness even while it threatens to consume.