The Muse of Maiden Lane Summary, Characters and Themes

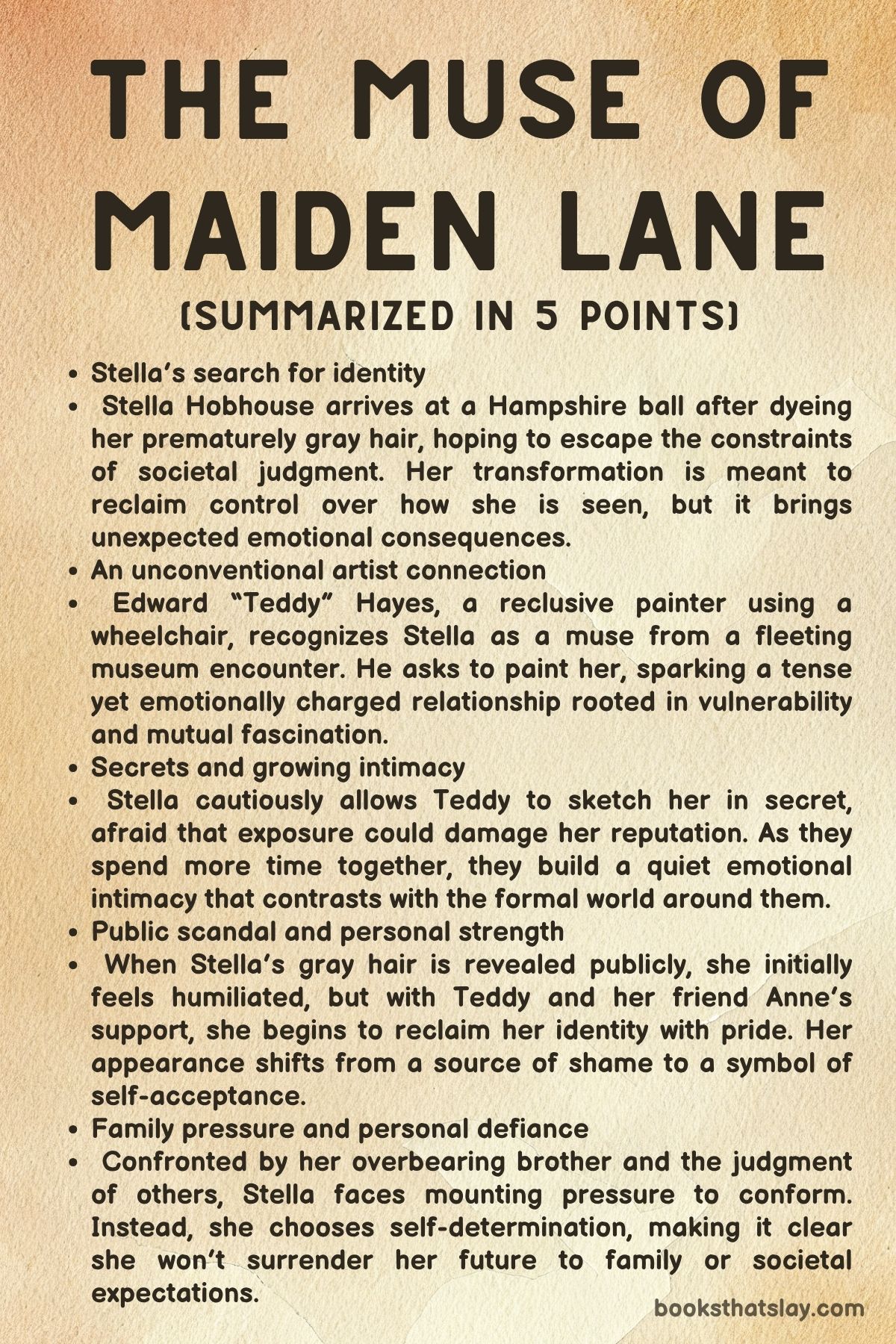

The Muse of Maiden Lane by Mimi Matthews is a tender and thoughtful historical romance set in 1860s England. At its heart, the novel follows the evolving relationship between Stella Hobhouse, a fiercely independent yet socially constrained young woman, and Edward “Teddy” Hayes, a brilliant artist who uses a wheelchair.

Their love story is not just about emotional connection but about the courage to be seen—both literally and metaphorically—in a society that thrives on appearances and conformity. Matthews crafts a romance that emphasizes emotional intimacy, mutual respect, and artistic passion, using rich period detail and nuanced character development to explore autonomy, identity, and the quiet power of choosing one’s own path.

Summary

In the spring of 1862, Stella Hobhouse arrives at a country house party at Sutton Park with a secret: she has dyed her prematurely gray hair a bold auburn in an act of rebellion and self-expression. The transformation is inspired by a painting and a brief but memorable encounter with an enigmatic artist at the British Museum.

That same artist, Teddy Hayes, unexpectedly appears at the party, revealing himself not as an anonymous observer but a well-connected guest. Mortified at being recognized, Stella retreats from the festivities, only to be found by Teddy himself.

Teddy, paralyzed from the waist down due to childhood scarlet fever, is forthright and emotionally disarming. He remembers Stella vividly and confronts her about her changed appearance with honesty, admiration, and artistic intensity.

Though Stella initially recoils at his boldness, she is quietly stirred by his attention. Teddy calls her a “shining star,” a phrase that strikes a deep chord in Stella, who is used to being overlooked or dismissed.

Their interaction marks the beginning of a dynamic that defies the social norms of their time.

Stella is the sister of a country vicar, with little financial security and dwindling prospects for a respectable marriage. The only suitor available to her is the unappealing Squire Smalljoy.

She struggles between the need for security and a yearning for something more meaningful. Teddy, for his part, is captivated not only by Stella’s physical beauty but also by her independent spirit.

Yet he recognizes the social constraints she faces, as well as the challenges posed by his own disability.

Over the course of the house party, the relationship between Teddy and Stella deepens through subtle and emotionally charged encounters. Stella’s attempt to re-dye her hair ends in a disastrous green tint, prompting a crisis of vanity that Anne, her pragmatic friend, helps her navigate.

The event highlights Stella’s vulnerability and the immense pressure on women to conform to narrow ideals of beauty and decorum. Teddy, meanwhile, is growing increasingly determined to assert control over his life, including his desire to settle in England and work as an artist.

Their emotional bond strengthens during a private meeting in a parlor where Teddy paints. The scene is intimate and transformative.

Teddy asks Stella to sit for a portrait. She hesitates but eventually agrees, recognizing that his request is not just about art—it is about truly seeing and being seen.

As he sketches her, Stella opens up about her frustrations with society, her failures in London’s social season, and her deep longing for autonomy. Teddy reciprocates with candid insights into his own struggles, his aversion to marriage, and his artistic philosophy.

Their collaborative sessions in the studio become a safe space where each can express their truths without fear of judgment. Teddy perceives Stella’s silver hair as something celestial rather than shameful, while Stella sees beyond Teddy’s chair to the man full of passion, intellect, and courage.

These sessions become the foundation of emotional intimacy, bridging the gap between societal roles and personal desire.

Separated after the party, Teddy writes to Stella from Greyfriar’s Abbey, hoping she will respond. She is isolated at her brother’s vicarage, stifled by the arrival of his fiancée and an overbearing future mother-in-law.

The letters between Stella and Teddy offer them both an emotional lifeline. Their correspondence is full of wit, affection, and unspoken yearning.

Through these exchanges, Teddy encourages Stella to envision a life outside the narrow confines of her village, while Stella’s spirit revitalizes Teddy’s artistic ambitions.

Determined to reclaim her freedom, Stella refuses to let her brother or societal expectations dictate her future. After a humiliating family confrontation, she accepts the help of her friend Julia and Julia’s roguish but reliable husband, Captain Blunt.

With their assistance, she travels to London for Anne’s wedding and is reunited with her circle of friends—the fiercely independent “Four Horsewomen”—who remind her of her worth and agency.

Teddy and Stella finally meet again in Hyde Park’s Rotten Row. Though watched by grooms and servants, their reunion is emotionally charged and affirming.

Teddy invites Stella to his studio, a subtle but unmistakable invitation into his world. Yet conflict arises when Teddy’s family pressures him to return to France.

Torn between duty and self-fulfillment, he must decide whether to reclaim his independence or surrender it once again.

Stella begins spending long hours in Teddy’s studio, posing for the portrait that has become both a professional ambition and a personal journey. Although she has grown more confident and independent, she remains unsure of Teddy’s feelings.

Is he truly in love with her, or simply infatuated with her as his artistic muse? Their engagement is defined more by routine and partnership than by open affection.

The delays in renovating their home, along with Teddy’s emotional reserve, exacerbate her doubts.

Eventually, a moment of emotional clarity comes when Teddy shares his insecurities. He fears being a burden due to his disability, but Stella affirms her love and desire to be with him not out of duty, but choice.

This breakthrough is accompanied by Teddy’s physical effort to try a new type of wheelchair—an act of hope and a symbolic reclaiming of agency.

Their wedding is quiet, personal, and deeply meaningful. Stella wears a butterfly-embroidered gown that symbolizes her transformation.

While unresolved insecurities linger, the ceremony confirms the authenticity of their feelings. That night, they consummate their marriage with tenderness and vulnerability, deepening their bond beyond art and physicality.

After the wedding, Teddy shows Stella the finished painting—Electra Descending—depicting her illuminated at twilight, confident and luminous. He promises never to sell it, claiming it belongs only to her.

This gesture encapsulates not just his love but his recognition of her full personhood.

Eighteen months later, the painting is exhibited in a London gallery. Though rejected by the Royal Academy, it garners acclaim.

Teddy and Stella, now a couple defined by mutual respect and creative freedom, walk through the gallery hand-in-hand. Stella is preparing to submit her own sketches, now a confident artist in her own right.

Their union is not built on perfection but on courage, honesty, and the shared determination to live authentically despite a world that once tried to keep them small.

Characters

Stella Hobhouse

Stella Hobhouse emerges in The Muse of Maiden Lane as a woman straddling the precarious divide between societal expectation and personal longing. Intelligent, observant, and quietly rebellious, Stella is not the typical Victorian heroine; rather, she embodies a nuanced resistance against the roles prescribed to women of her class and time.

Her choice to dye her prematurely gray hair is a symbolic assertion of agency, an effort to reclaim beauty and vibrancy in a world that sees her as prematurely aged and unremarkable. This outward act reflects her inward yearning to be seen—not just looked at—and to possess control over how she is perceived.

Stella’s bond with her horse, Locket, becomes a surrogate for the freedom she lacks in her domestic sphere, while her emotional detachment from societal gatherings—like the ballroom scenes—demonstrates her disillusionment with the performative nature of aristocratic life.

Stella’s emotional arc is shaped largely through her relationship with Teddy Hayes. Initially guarded and mortified by his attention, she gradually softens, drawn to his honesty, artistic vision, and the profound way he sees her.

For Stella, Teddy’s act of painting her becomes not an act of objectification but one of liberation; it offers her a mirror in which she is not judged but celebrated. Her growing independence—choosing to go to London, resisting her brother’s authority, refusing an unfulfilling marriage—signals a woman awakening to her own desires.

The tenderness and sensuality she brings into her eventual marriage with Teddy further highlight her evolution from a woman constrained by reputation to one living a life of emotional and artistic authenticity.

Edward “Teddy” Hayes

Teddy Hayes, the disabled artist at the heart of The Muse of Maiden Lane, is a study in contrasts: physically limited but emotionally daring, socially awkward yet profoundly perceptive. Stricken with paralysis due to scarlet fever, Teddy inhabits a world that often underestimates or infantilizes him, yet he refuses to let his condition define his identity or art.

His wheeled chair, while symbolizing physical limitation, becomes almost a throne from which he observes and interprets the world with clarity others lack. Teddy’s first encounter with Stella sparks an obsessive artistic desire that borders on reverence—he sees in her the embodiment of beauty, depth, and story.

Unlike many male protagonists in historical romance, Teddy does not dominate through power or wealth; instead, he earns respect through emotional openness, creative intensity, and vulnerability.

His relationship with Stella becomes a crucible for his transformation. Initially frustrated by her distance and ashamed of the dependence his condition imposes on others, Teddy grows into someone capable of loving and being loved beyond the confines of the canvas.

His decision to settle in London, to procure a studio and attempt a new form of mobility, reflects a man taking charge of his destiny. His desire to paint Stella is less about possession and more about communion—it is his way of immortalizing not just her image, but the transformative effect she has had on him.

By the time of their marriage, Teddy is no longer just an artist in search of a muse; he is a man who has fought for love, autonomy, and purpose in a world that offered him little of either.

Anne and Mr Hartford

Anne, Stella’s loyal friend, operates as a counterpoint to Stella’s internal turmoil. Grounded, practical, and well-adjusted to the norms of their world, Anne represents the ideal path society expects respectable women to take—an advantageous marriage, cheerful acceptance of domesticity, and an unwavering commitment to decorum.

Yet, she never becomes a caricature of conformity. Her support during Stella’s hair-dye disaster shows a warmth and loyalty that transcends societal etiquette.

Through Anne’s engagement to Mr Hartford, the narrative juxtaposes Stella’s uncertain future against the seeming security of traditional choices. Mr Hartford himself is not deeply developed, but his role is emblematic—he is the safe, respectable match, the kind of man a woman like Stella might be expected to settle for.

Together, Anne and Mr Hartford provide a mirror for what Stella might become if she surrendered her independence and artistic inclinations.

Reverend Hobhouse and His Fiancée

Stella’s brother, Reverend Hobhouse, and his overbearing fiancée, along with her socially ambitious mother, embody the suffocating patriarchal and moralistic pressures of Victorian society. The Reverend, though well-meaning in his clerical duties, treats Stella more as a ward than an equal.

He exerts control over her choices, dismissing her artistic interests and romantic longings as frivolous or inappropriate. His fiancée, eager to assume authority within the household, escalates Stella’s sense of displacement and lack of agency.

These characters are not just familial obstacles—they are societal proxies, embodying the cultural norms that Stella must reject in order to live authentically. Their attempts to arrange her future without her consent catalyze Stella’s ultimate rebellion and choice to carve out a life on her own terms.

Alex and Laura

Alex and Laura, Teddy’s brother-in-law and sister, offer a more complex familial relationship—one of concern, affection, but also quiet tension. Laura’s protective instincts toward her brother are understandable, but at times they verge on infantilizing him.

She believes she knows what’s best for Teddy and tries to steer him away from disappointment or hardship, even if it means undermining his autonomy. Alex, though more relaxed, reflects the rational, socially compliant male voice that warns Teddy of the risks of romantic entanglement and artistic obsession.

Yet neither Alex nor Laura is antagonistic. Instead, they represent a familial love that is cautious and compromised by fear—a fear that Teddy’s pursuit of Stella and a life in England might end in rejection or worse.

Their eventual acceptance of Teddy’s independence reflects a subtle but meaningful shift in the narrative’s depiction of familial duty.

Julia and Captain Blunt

Julia and Captain Blunt, though appearing later in the novel, inject a necessary dose of daring and subversion. As part of the “Four Horsewomen,” Julia embodies female solidarity, agency, and wit.

Her marriage to the scandalous Captain Blunt—who, despite society’s scorn, proves to be a staunch ally—challenges the era’s rigid moral codes. Julia assists Stella in her escape to London, enabling her to seize control of her fate.

Captain Blunt’s role is more limited, but he stands as a symbol of masculine loyalty that supports rather than controls. Together, they are a reminder that love and partnership can exist outside the bounds of societal approval, and that allies—regardless of reputation—are crucial in the journey toward self-determination.

Locket

Though not a person, Stella’s horse Locket functions as a powerful symbol throughout The Muse of Maiden Lane. Locket represents freedom, childhood innocence, and emotional sanctuary.

The forced separation from her beloved horse at the start of her stay in Hampshire reflects Stella’s initial loss of agency and comfort. Later, Locket’s return to her life coincides with Stella’s own reclamation of independence.

Riding Locket becomes a physical expression of Stella’s freedom—both from her family’s control and from the limitations of her own fear. In the final act of the novel, when Stella rides to Rotten Row, Locket serves as the bridge between her old self and the new, reminding both Stella and the reader that some forms of freedom are both literal and metaphorical.

Together, these characters form a vivid tapestry in The Muse of Maiden Lane, illuminating a story of love, art, resilience, and defiance in the face of societal constraint. Through Stella and Teddy’s journey, the novel celebrates not just romantic love, but the radical power of being truly seen—and truly loved—for who one is.

Themes

Visibility and Invisibility

Stella Hobhouse’s transformation—dyeing her gray hair a bold auburn hue—is the first act of defiance against a life of societal invisibility. Though she lives in a world where a woman’s social currency is tightly bound to her youth, beauty, and marital prospects, Stella’s decision reflects a desperate need to be seen, acknowledged, and affirmed.

The paradox, however, lies in how this visibility becomes a double-edged sword. When she is recognized and scrutinized by Teddy Hayes, the very artist who inspired her transformation, the moment of visibility becomes a source of both shame and awakening.

As the story unfolds, Stella’s fluctuating relationship with her hair—ranging from coloring it to conceal its silverness to embracing it once Teddy calls it beautiful—mirrors her internal battle over whether to hide or accept her identity. This theme matures into a broader reflection on societal pressures: how women are taught to retreat into the background once they lose their ornamental value, and how reclaiming space in the world is both revolutionary and perilous.

The repeated physical retreats—Stella hiding in the ballroom, concealing herself under a matron’s black cap, or escaping her brother’s home—are not just plot devices but symbolic manifestations of her struggle between craving attention and fearing the vulnerability that comes with it. Ultimately, it is only when she embraces her visibility, through Teddy’s art and their eventual partnership, that she finds liberation from the rigid expectations that sought to make her disappear.

Artistic Expression and Emotional Truth

The relationship between artist and muse is not a backdrop but the lifeblood of the narrative. Teddy Hayes does not merely want to paint Stella; his very sense of purpose and artistic worth is bound to capturing what he sees as her inner light.

The act of painting becomes more than a pursuit of beauty—it becomes a pursuit of emotional truth. Teddy’s artistic lens allows him to see Stella in ways that society refuses to: not as a spinster with prematurely gray hair, but as a woman of brilliance, depth, and defiance.

Their sketching sessions turn into emotional interrogations, each one peeling back layers of insecurity, social trauma, and desire. This emotional nudity creates a space where Stella can begin to imagine herself not just as someone seen but someone understood.

The portrait, Electra Descending, emerges not only as a masterpiece in paint but as a declaration of Stella’s transformation. Similarly, Stella’s own growth into an artist signifies her transition from object to creator, from being defined by the male gaze to wielding her own.

Through art, both characters forge a new language—one in which their relationship can exist outside the constraints of class, gender, and physical ability. Art becomes both mirror and window: a reflection of their internal selves and a projection of what their lives might become if shaped by authenticity rather than expectation.

Disability and Autonomy

Teddy’s physical paralysis is not portrayed as tragedy but as a condition that has redefined his relationship with autonomy, masculinity, and social interaction. While others treat his disability as something that must be managed or compensated for, Teddy refuses to be pitied or diminished.

His disability limits his mobility but not his agency, intellect, or sensuality. The early scenes at Sutton Park showcase his frustration at being excluded from traditional masculine activities like hunting or riding, but he redirects his energy into asserting artistic control and personal independence.

His decision to remain in England, away from his protective family, is an act of self-definition. Yet, the fear of being a burden continues to haunt him, especially in his relationship with Stella.

This anxiety reaches its apex when they discuss marriage, with Teddy fearing he is being loved out of duty, not desire. Stella’s refusal to nurse him, and her insistence on being his partner rather than his caretaker, dismantles the patronizing lens through which disability is often viewed in historical romance.

Teddy’s journey into a pneumatic wheelchair and his determination to maintain an active professional life highlight the complexity of his pursuit for autonomy—not as a denial of his condition, but as an assertion of identity beyond it. In pairing him with Stella, the novel asserts that love and desire do not require physical perfection, only emotional courage.

Feminine Agency and Resistance

From the very first scene, Stella Hobhouse exists in conflict with the expectations imposed on her. As a clergyman’s sister with limited prospects, she is positioned as someone whose future must be negotiated through marriage, obedience, and propriety.

Yet her every action—dyeing her hair, escaping from her brother’s oppressive household, posing for Teddy, and eventually moving to London—signals a quiet but determined rebellion. Stella’s choices are rarely grand gestures; rather, they are incremental acts of defiance that slowly accumulate into a portrait of resistance.

Her friendships with the self-styled Four Horsewomen reveal how community and solidarity among women can foster liberation, especially when the outside world offers little support. These women, all marginalized in different ways, form a network that validates each other’s choices, offering emotional and practical aid.

The climax of Stella’s rebellion is not just her departure from home but her declaration of love on her own terms—refusing to accept a marriage of convenience or be treated as a helpless spinster. Her ultimate evolution into an artist, a wife, and a woman who is publicly admired and personally fulfilled, affirms the central message: agency is not granted, it is claimed, often at great cost.

The narrative honors the quiet revolution of feminine self-determination in a society that systematically denies it.

Love as Mutual Recognition

The love story in The Muse of Maiden Lane is less about romantic fantasy and more about mutual recognition—the rare, radical act of truly seeing and accepting another person in their entirety. Teddy sees Stella not through the eyes of society, but through the eyes of an artist and a man in love.

He notices not her gray hair but the light in it, not her unmarried status but her strength and curiosity. Likewise, Stella does not see Teddy as a man diminished by a wheelchair, but as someone brimming with brilliance, humor, and sensuality.

Their love is born in moments of vulnerability: letters written from a place of loneliness, sketches drawn in silence, conversations where truth is shared without pretense. Even their physical intimacy is marked not by idealized passion but by tenderness, pain, and mutual care—an embodiment of their deeper emotional connection.

Their relationship is not one of rescue, nor of dominance, but of equilibrium. Each partner uplifts the other while respecting the individual journeys they are on.

In the end, love is not the destination but the affirmation of everything they have become through each other’s presence. It is a celebration of chosen companionship over prescribed roles, of emotional truth over societal approval, and of finding home not in a place, but in a person who sees you clearly and loves you anyway.