The Story of the Forest Summary, Characters and Themes

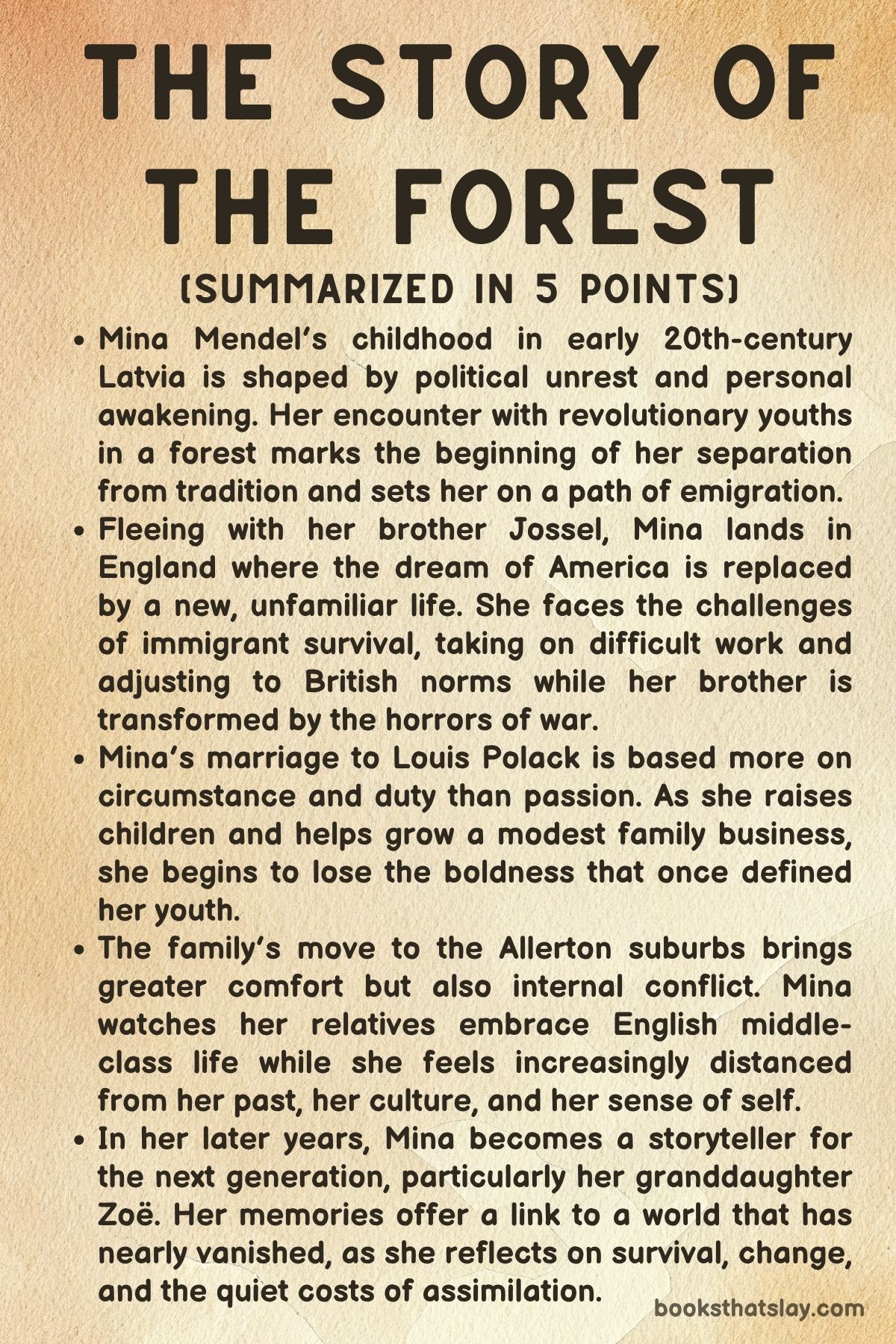

The Story of the Forest by Linda Grant is a multi-generational family saga that traces the Mendel and Polack families across the turbulent currents of the twentieth century, from the pogrom-threatened forests of Latvia to the bombed streets of Liverpool and the cultural enclaves of post-war London. With a focus on Jewish identity, migration, memory, and transformation, the novel explores how the past reverberates through generations.

At the center of the story are Mina Mendel and her daughter Paula, whose lives serve as prisms through which broader themes—war, class, feminism, and cultural assimilation—are refracted. Rich in detail, the novel is a meditation on the evolving nature of identity and the legacy of survival.

Summary

The novel begins in the early twentieth century with fourteen-year-old Mina Mendel, a Jewish girl growing up in Latvia. Her journey toward womanhood is catalyzed by a brief but emotionally significant encounter in the forest outside Riga, where she meets a group of young revolutionaries.

Among them is Andrievs, a boy whose brief kiss becomes a symbol of Mina’s burgeoning awareness of personal desire and political awakening. Her younger brother Itzik, a dark and calculating presence, secretly witnesses this moment and uses it to undermine her within the family.

As tensions rise in the Jewish community under the tsarist regime, Mina’s older brother Jossel plans a way out. With the quiet support of their enigmatic mother Dora, Jossel and Mina flee to the West, setting off for a new life.

Their journey takes them to Liverpool, a temporary stopping point that becomes permanent due to the outbreak of World War I. Here, Jossel marries Lia, a sharp and capable widow who quickly assumes leadership of the small family unit.

They settle into life among a working-class immigrant community, and Mina adopts the name Millie. Their lives revolve around adaptation—Jossel becomes a bookkeeper, Lia focuses on assimilation, and Mina tries to reconcile her past with her uncertain future.

Mina finds work in a canteen at a munitions factory, where she is introduced to the harsh realities of British working-class life. Though initially viewed with suspicion by the other women, she earns their respect and becomes part of the group.

Her past in the Latvian forest remains a source of longing and unresolved identity, and she continues to dream of America and what might have been. When Louis Polack, a fellow Jewish soldier injured in the war, arrives to fulfill Jossel’s joking suggestion that he marry Mina, she accepts his proposal.

Their marriage is one of mutual respect and security, rather than romantic passion, and they co-manage a family business producing chamois leather.

The family gradually climbs the social ladder and moves to Allerton, a more genteel suburb of Liverpool. This shift prompts a reevaluation of identity and appearance, particularly for Lia and Mina.

Lia undergoes a physical transformation to match English middle-class ideals, while Mina remains more rooted in her immigrant origins. A letter from her sister Rivka reveals the fate of the family left behind in Latvia: their father executed, Itzik vanished, and the remaining relatives absorbed into the Soviet state.

Mina mourns but accepts the loss with resignation.

Despite a seemingly stable domestic life, Mina begins to experience a personal crisis. She has a sensual encounter in a hair salon that awakens dormant desires and insecurities, shaking the foundation of her identity.

Around the same time, she briefly meets a Communist doctor, which stirs memories of her youthful idealism and underscores how far she has moved from those convictions.

Attention shifts to Paula, Mina’s daughter, who begins her adult life in London after the war. Living in a modest boarding house, Paula struggles to bridge the gap between her provincial upbringing and the urbane sophistication of post-war intellectual circles.

Her relationship with Roland, a charismatic yet patronizing man, highlights her social vulnerability and her ongoing quest for belonging. Roland exploits Paula’s outsider status while diminishing her intellect and heritage.

Through Roland, Paula secures a job at Harlequin Pictures, which leads her deeper into the cultural world. A family encounter with her boss, Eric Fulton, at a Christmas lunch reassures her parents of her legitimacy in London and boosts her professional confidence.

The studio plans a film inspired by a story from Mina’s youth, commodifying the family’s private past. Mina, flattered yet uneasy, sells the rights for £500, giving the family access to luxuries like a trip to Cannes.

The film marks a turning point in Paula’s and Mina’s self-perceptions—one as an emerging cultural figure, the other as a reluctant symbol.

Paula begins an affair with Eric Fulton, a married man much older than she. The relationship is less emotionally volatile than her time with Roland but fraught with its own complications.

Her decision to pursue the affair reflects her growing sense of autonomy and complexity. Meanwhile, Uncle Itzik, once a shadowy figure of menace, reemerges in the narrative as a retired Soviet official living in isolated exile.

His life has collapsed into obscurity, and he is left to stew in bitterness and fading relevance. A chance viewing of the film about Mina’s forest memory aggravates his sense of erasure.

Mina’s final years are marked by the death of her husband Louis and a descent into depressive isolation. Her grief is compounded by overmedication and hallucinations, which Paula and Ringo attempt to manage.

A visit from cousin Bernice, whose own life has taken a radical turn toward activism, reinvigorates Mina. She becomes engaged in political protests, especially in support of Soviet Jewry, linking her private history to broader causes.

Meanwhile, Itzik dies alone, a minor footnote in a grander family story he once sought to control.

As Mina ages into her hundreds, her death is quiet and private. Paula, now burdened with both practical and existential responsibilities, consents to a morphine injection that ends her mother’s life.

The novel does not romanticize this moment but renders it in intimate detail—death as a presence, not just an event. At the funeral, stories circulate, blending truth with myth.

Mina’s granddaughter Shelley brings her own daughter Zoë, who watches the rituals with detachment, signaling a growing distance from the family’s Jewish traditions.

In the closing pages, Mina’s legacy is embodied not just in film or memory but in fragments—scarves, whispered stories, and contradictory versions of truth. The final gesture of tucking Mina’s protest scarf around her in death is both reverent and symbolic.

The forest of her youth, literal and metaphorical, is never far from the narrative’s edge, representing both the mystery of origins and the inevitability of change. The Story of the Forest ends not with resolution, but with continuity, asking what remains when those who remember are gone.

Characters

Mina Mendel (later Mina Phillips)

Mina is the beating heart of The Story of the Forest, an emblem of resilience, transformation, and generational memory. Born into a Jewish family in early 20th-century Latvia, she begins as a curious, independent adolescent whose defining moment—a kiss with a Bolshevik boy in a forest—becomes a lifelong metaphor for liberation, loss, and the cost of change.

Her journey from revolutionary-tinged Latvia to war-torn Liverpool charts the migrant experience with poignancy and realism. In England, Mina straddles conflicting identities: immigrant and citizen, mother and woman, rebel and conformist.

Though her marriage to Louis Polack is one of obligation, it provides stability and respectability. Yet, beneath the surface, Mina’s memories and desires churn.

Her crisis of identity, illustrated through an illicit encounter and political nostalgia, signals the price she pays for safety and assimilation. In old age, she reclaims fragments of her past through activism and family storytelling.

Her death is quiet yet profound, mirroring her life’s blend of intensity and suppression. Mina’s legacy is not just the forest of her past but the forest of memory, myth, and identity passed on to her children and grandchildren.

Jossel Mendel

Jossel is a moral anchor and tragic philosopher, whose evolution underscores the intellectual and emotional burdens of migration. Initially an idealistic older brother desperate to protect Mina from scandal and stagnation, Jossel initiates their emigration, guided more by dreams than practicality.

His philosophical leanings and emotional reticence are both shield and weakness. War changes him irrevocably: he returns from Palestine as a disillusioned veteran, having endured trauma and self-sacrifice in caring for Louis.

His later life in Liverpool is marked by work in the chamois leather business and domestic entrenchment. Despite his rationalism, he displays bursts of emotional vitality, particularly in old age—such as his decision to throw away Mina’s sedatives to protect her spirit.

Jossel is both burdened by memory and wary of myth-making. His quiet heroism lies in the choices he makes for others, even when they bring him no reward or peace.

Louis Polack

Louis is a complex figure, shaped by duty, loyalty, and suppressed artistry. His war injury and near-death experience catalyze a sense of obligation to Jossel and, by extension, Mina.

His marriage to Mina is less about romance than atonement and necessity, but he builds a stable family life, taking pride in his business and domestic legacy. Yet Louis carries secret longings—especially for art and aesthetics—that he rarely articulates.

He is a man whose love is expressed not through grand gestures but quiet devotion: his support of Paula, his respect for Mina’s autonomy, and his consistent, if unremarkable, presence. Louis’s inner world remains largely inaccessible, but its contours emerge in his silent admiration of beauty and in his nuanced support for Paula’s ambitions.

His death, though not dramatized, casts a long emotional shadow over the family.

Paula Polack

Paula represents the generational pivot in The Story of the Forest, embodying both continuity and rupture. The daughter of Mina and Louis, she grows up in the assimilated suburbs of Liverpool but harbors a yearning for complexity, ambition, and escape.

Her move to London initiates a metamorphosis: from provincial girl to a savvy, if conflicted, cultural operator in the post-war film world. Her relationships—with the toxic Roland and the older, enigmatic Eric Fulton—mirror her ongoing struggle with power, validation, and self-definition.

Yet Paula is not a victim of these dynamics. She uses them, discards them, and ultimately claims a form of independence.

Her work at Harlequin Pictures, and particularly the production of The Story of the Forest, positions her as both curator and commodifier of family history. Her moral discomfort with this process reveals a complex awareness of the ethics of storytelling.

Paula becomes the narrative’s bridge between old world and new, between legacy and reinvention. She inherits her mother’s strength but channels it into professional agency and aesthetic detachment.

Lia Mendel

Lia is the sharp-tongued, pragmatic widow who becomes Jossel’s wife and Mina’s sister-in-law. She embodies the fortitude and adaptability of women thrust into leadership roles within immigrant families.

Lia’s early role as caretaker and organizer positions her as the stabilizing force in the Mendel family’s English chapter. She orchestrates their transition into English society, pushing for name changes, managing the household, and navigating social advancement with clarity and will.

Her fascination with suburban English femininity leads to self-reinvention, which in turn prompts Mina’s own reflections on identity. Though Lia is not the emotional center of the novel, she is one of its practical backbones.

Her legacy lives through her decisions that shape the family’s integration, even if her emotional interior remains guarded and opaque.

Itzik Mendel

Itzik is a haunting presence—initially a voyeuristic, threatening boy who matures into a morally ambiguous Soviet official. From the start, he disrupts familial intimacy with his intrusion on Mina’s forest awakening, symbolizing the surveillance and judgment that permeate repressive societies.

His trajectory from Latvia to the Soviet diplomatic corps reveals a life steeped in secrecy, opportunism, and ultimately, loneliness. Though he seems powerful, his exile and erasure in old age render him pitiful.

His bitter viewing of the film adaptation of Mina’s life highlights his resentment at being edited out of the family narrative. He is a figure of warning: someone who survives but never quite lives.

His existence challenges the romanticism of revolution and the myth of legacy, showing instead the erosion of identity through ideological servitude.

Bernice

Bernice is a late-blooming catalyst in the novel. Her personal traumas—particularly her failed marriage to a closeted man—lead her to reinvent herself as a political activist, especially for Soviet Jewry.

She becomes a surprising but effective force of renewal for Mina, dragging her out of depressive inertia and back into public life. Bernice’s arc is one of transformation through humiliation, turning personal pain into communal strength.

Though she does not occupy a central role in the plot, her energy and assertiveness ripple through the family, particularly influencing Mina’s final chapter. She embodies a late-in-life reclamation of agency, political consciousness, and communal responsibility.

Roland

Roland is an emblem of post-war British elitism and cultural gatekeeping. Charismatic and manipulative, he draws Paula into a performative and toxic relationship.

He both fetishizes and mocks her Jewishness and outsider status, using his cultural fluency as a weapon of dominance. His treatment of Paula—alternately seductive and cruel—illustrates the insidious forms of class-based discrimination masked as intellectualism.

Yet he inadvertently helps propel Paula into the film industry, making him a perverse midwife to her transformation. Roland is a cautionary figure, representing a seductive but corrosive vision of cultural sophistication devoid of empathy or authenticity.

Eric Fulton

Eric represents power, possibility, and ethical ambiguity. As Paula’s employer and eventual lover, he straddles the line between mentor and opportunist.

Twice her age and married, his relationship with Paula is less exploitative than it is morally ambiguous, grounded in mutual need rather than romance. He offers her professional advancement, a glimpse into the inner workings of art and commerce, and access to a world she once idealized.

Yet their affair underscores the gendered dynamics of power in creative industries. Fulton is less a villain than a symbol—of what is possible for women like Paula, and what it costs.

Shelley and Zoë

Shelley, Paula’s daughter, and Zoë, her granddaughter, represent the future—detached from Jewish tradition, curious but disconnected. Their presence at Mina’s funeral and their reactions to the rituals expose the cultural drift across generations.

Shelley serves as a transitional figure, still somewhat anchored in heritage, while Zoë is its observer—removed, questioning, emblematic of modern cosmopolitan youth. Through them, the novel articulates the fear of forgetting, the erosion of cultural specificity in the diaspora, and the fragility of memory in the face of time’s onward march.

Their inclusion reaffirms that legacy is always incomplete, always rewritten, and always vulnerable to silence.

Themes

Assimilation and Cultural Identity

In The Story of the Forest, the shifting nature of Jewish immigrant identity across time, geography, and generations is one of the most complex and emotionally resonant elements. The characters navigate multiple layers of cultural affiliation—Yiddish-speaking Eastern European origins, diasporic dislocation, British working-class life, and eventual suburban comfort.

At every stage, identity is neither stable nor fully embraced by the surrounding society. Mina and her family must constantly recalibrate their accents, clothing, behaviors, and names to fit new cultural milieus, from Liverpool tenements to middle-class Allerton, and eventually to cosmopolitan London.

Even the act of translation—from Yiddish to English, from private experience to cinematic representation—illustrates the costs and consequences of assimilation. Mina’s daughter Paula embodies this fluidity most acutely, speaking like the English elite while never fully accepted into their cultural echelons.

This theme asks painful questions about what is lost when trying to belong—ancestral language, tradition, and even the ability to recount one’s own story without distortion. It also shows the generational divide that arises from this process; what is necessity for survival to one generation becomes invisibility or shame to the next.

Assimilation here is not triumphant but melancholic, a constant negotiation between visibility and erasure, pride and displacement. The title’s metaphorical forest—dense, symbolic, and hard to navigate—serves as an apt setting for these shifting identities.

The closer one gets to assimilation, the further away one moves from their origin point, and this friction drives much of the narrative’s emotional weight.

Female Autonomy and Sexual Awakening

From Mina’s kiss in the Latvian forest to Paula’s fraught affairs in London, the novel consistently explores the inner lives and desires of women across generations. These moments of sexual or emotional awakening are not simply romantic episodes but pivotal junctures of self-definition.

Mina’s first intimate experience with Andrievs sets in motion her estrangement from her home, her transformation into a migrant, and ultimately, her role as a matriarch in a new land. Yet that spark of independence and longing is repeatedly tempered by social constraints—her marriage to Louis is founded not on passion but on duty.

Despite achieving a form of stability, she is haunted by what she has suppressed, culminating in her transgressive moment of desire in the salon’s backroom. Paula, in turn, experiences her own form of awakening, first through toxic relationships with men like Roland, who exoticizes and condescends to her, and later through more ambiguous entanglements with older, married men like Eric Fulton.

Each woman negotiates her autonomy differently, shaped by the constraints of her time and class. The story doesn’t present a linear evolution of female empowerment but rather portrays a cyclical pattern of repression, fleeting liberation, and compromise.

The women’s sensual lives are never isolated from the broader context—they are entwined with labor, migration, motherhood, and memory. These awakenings are not solutions; they are ruptures in the surface of domestic life that allow hidden truths, yearnings, and regrets to surface, often with lasting repercussions.

Memory, Legacy, and the Unreliability of Narrative

A central concern of The Story of the Forest is how stories are preserved, altered, or forgotten over time. As the Mendel-Polack family spreads across countries and decades, their collective memory becomes increasingly fragmented.

Mina’s kiss in the forest, for example, is passed down as lore, reinterpreted and ultimately commodified in a fictionalized film. What was once a private, transformative experience becomes public art, stripped of nuance and transformed into legend.

This process of narrative distortion occurs at multiple levels. The family’s Holocaust-era trauma is selectively remembered or deliberately occluded, while characters like Itzik disappear into ideological obscurity, resurfacing only at the margins.

The film industry’s appropriation of family stories amplifies this distortion. What Eric Fulton directs is not the truth of Mina’s life, but a product shaped by commercial, aesthetic, and political demands.

Paula becomes a gatekeeper of these stories, caught between honoring her family’s experiences and capitalizing on them. The final sections emphasize this tension through Mina’s death and the rituals surrounding it.

Her scarf, a once-radical symbol, is transformed into a token of farewell. The younger generation, especially Zoë, receives this legacy not as a coherent history but as puzzle pieces lacking context.

The narrative asks what it means to “know” one’s heritage when that knowledge is mediated through unreliable tellers, selective memory, and cultural drift. The past is not preserved in amber—it is fluid, rewritten by those who survive and by those who choose what is worth retelling.

Displacement, Migration, and the Search for Home

Migration is not merely a backdrop in this novel—it is a lifelong condition experienced across bodies, borders, and generations. From the forests of Latvia to the working-class streets of Liverpool, from the war-ravaged landscapes of Palestine to the elite offices of London’s film industry, characters in The Story of the Forest are always in motion, both physically and emotionally.

The early escape of Mina and Jossel sets the tone, a gesture of both survival and disinheritance. They carry the weight of those left behind, some of whom meet tragic ends, like their father’s execution or their siblings’ Soviet re-education.

Migration offers freedom, but it also creates permanent loss. The theme is reinforced in the transient spaces the characters occupy—boarding houses, refugee districts, temporary workplaces—none of which feel like home.

Even the suburban homes of later years, though symbols of class advancement, fail to provide emotional permanence. Characters yearn for a home that is neither the place they left nor the one they inhabit.

This search becomes internalized in Paula’s longing for belonging in London, and in Mina’s late-life hallucinations of animals crawling from the wallpaper, symbolizing unease with settled life. The book refuses to romanticize migration as a journey toward betterment.

Instead, it presents it as a constant negotiation with grief, nostalgia, and compromise. It asks whether a true home can exist for those shaped by displacement, or whether they are destined to remain travelers in both land and memory.

Generational Guilt and Inheritance

The emotional inheritance passed from one generation to the next in The Story of the Forest is not merely one of wealth or tradition—it is composed of silence, trauma, missed opportunities, and the unspoken burden to carry forward stories that the previous generation could not articulate. Jossel’s protective act of fleeing with Mina to the West becomes a source of gratitude but also a rupture, causing separation from the rest of the family and inciting guilt over their fate.

Mina’s own life becomes shaped by these decisions, haunted by memories of her siblings and a sense of irrevocable loss. When she dies, her children and grandchildren are left to piece together a narrative that has been obscured by time, shame, and the subjectivity of memory.

Paula bears much of this generational weight, often unconsciously. She inherits not only her mother’s physical keepsakes but also the need to make sense of a fractured past.

Her decisions—whether to have an affair, to work in film, or to define her Jewishness—are made under the looming presence of family precedent. Even Zoë, Paula’s granddaughter, stands as a symbol of diluted continuity.

She witnesses rituals and hears stories, but they feel alien to her. This theme interrogates the nature of inheritance not as a gift but as a responsibility, and sometimes a burden.

It questions what future generations owe to the past: preservation, reinterpretation, or liberation from its grip. In doing so, it provides a poignant commentary on how history lives within families long after the events have faded.