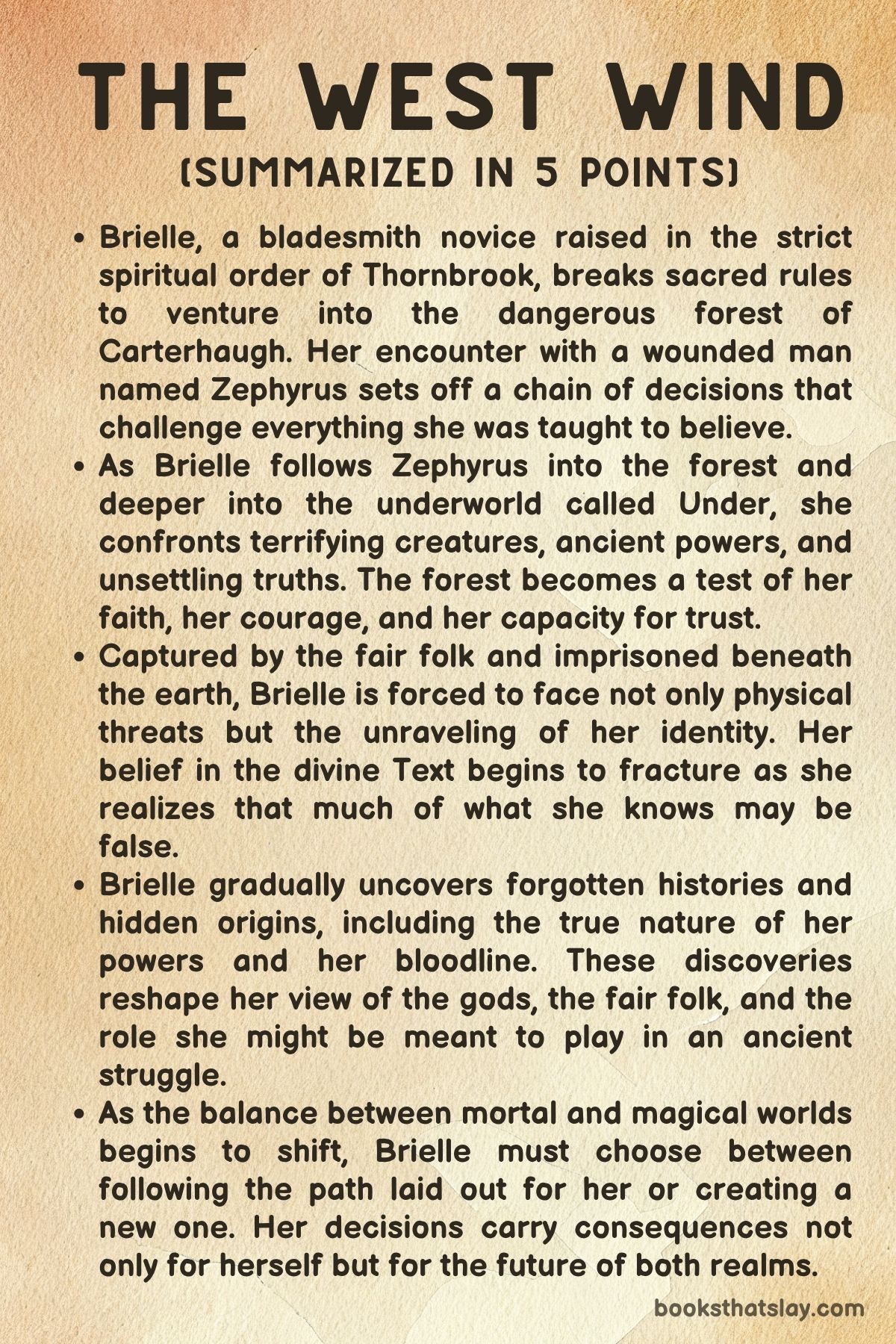

The West Wind Summary, Characters and Themes

The West Wind by Alexandria Warwick is a richly imagined fantasy novel that explores the struggle between duty and desire, faith and freedom, through the journey of a devout novitiate named Brielle. Set in the insular Thornbrook Abbey, a place bound by divine law and ancient pacts, the story plunges Brielle into the perilous and sensual realm of the fair folk, where reality bends and morality blurs.

Through her encounters with Zephyrus, a mysterious being with divine origins, Brielle is forced to confront her beliefs, her identity, and her place in a world where sacred rules often conceal darker truths. This is a tale of love, sacrifice, betrayal, and the relentless pursuit of selfhood.

Summary

Brielle is a novitiate at Thornbrook Abbey, a secluded religious sanctuary that forbids the presence of men. One day, while wandering in the forest of Carterhaugh—a place rumored to be haunted by fair folk—she finds a man bleeding and near death.

Compassion outweighs obedience, and she secretly brings him into the Abbey. The man, Zephyrus, insists he is not fair folk, though his strange healing powers and connection to a shadow realm called Under suggest otherwise.

Brielle hides him in her private quarters, risking banishment, while grappling with her own conscience and devotion. Zephyrus claims his wounds were inflicted by his brother, and his vague explanations add to the mystery surrounding his identity.

As Brielle cares for him, she also contends with pressures within the Abbey. Despite years of devotion, she remains unsure if she’ll ever be chosen as an acolyte—a highly respected position.

Her rivalries with Harper and Isobel, both cruel and competitive, intensify her feelings of inadequacy. Just as suspicions begin to grow about her behavior, Zephyrus disappears.

He later returns, offering a deal: accompany him to Under to meet a being called Willow in exchange for a debt repaid. Hungry for spiritual recognition and desperate to find her place, Brielle agrees.

They descend into Under through a magical spring. Zephyrus gives her strict rules—don’t eat or drink, don’t stray from the path, don’t speak her name aloud.

Under is a land of bizarre, dreamlike terrors and sensual temptations. The fair folk who reside there are bound by twisted customs and ancient bargains.

Willow, a luminous talking tree, provides cryptic wisdom but no clear answers. Zephyrus soon vanishes, leaving Brielle to navigate Under alone.

She meets a sprite named Lissi, who reveals that Zephyrus is actually a god—the West Wind—and one of the exiled Anemoi. Zephyrus’s fate is entangled with the realm of Under and with Pierus, the Orchid King, its cruel ruler.

Brielle witnesses horrific and sensual spectacles that challenge her religious ideals. The Orchid King forces Zephyrus into a gruesome ritual where he is pierced and drained by carnivorous flora.

The event is both a demonstration of dominance and a grim warning. Traumatized, Brielle returns to Thornbrook to find a week has passed though she believes only a night had gone by.

She is punished with seven lashes and further isolated within the Abbey. Despite the physical and emotional toll, she clings to her faith and yearning for purpose.

Zephyrus appears again to apologize and offer healing, but Brielle rebuffs him, unable to forgive his deceptions. Their relationship sours, charged with unresolved feelings and mutual pain.

Meanwhile, Brielle is offered a chance to compete for the acolyte title. Her rivalry with Harper comes to a head, but the animosity begins to shift.

Harper eventually shows remorse and vulnerability, leading to a tentative reconciliation.

Brielle embarks on another dangerous mission to retrieve Meirlach, a legendary god-forged sword. In the Stallion’s Grotto, she challenges a kelpie and wins the blade by showing restraint.

Zephyrus and Harper arrive, but Zephyrus’s motives are questioned. Brielle accuses him of manipulation, and he admits he initially sought the sword for selfish reasons.

Heartbroken, Brielle rejects him, expels him from Thornbrook, and threatens death should he return. Harper comforts her, and their dynamic shifts from rivalry to fragile friendship.

Despite being offered spiritual promotion, Brielle declines, plagued by uncertainty. She throws herself into forging daggers for the upcoming tithe—a blood ritual that sustains the Abbey’s lease on its land.

Zephyrus’s roselight—a magical orb connected to him—glows ominously during the tithe, signaling his suffering. Compelled by compassion, Brielle sneaks away and re-enters Under.

She finds Zephyrus nearly dead, consumed by vines that feed on his divine energy. Lissi agrees to help in exchange for the sacred Text, revealing that Zephyrus powers Under’s life force.

Brielle rescues him, bearing witness to the depth of his torment and sacrifice. Her growing defiance of divine rules marks a profound transformation from a compliant novitiate to someone who challenges oppressive authority in the name of love and justice.

Together, they return to confront Thornbrook’s hidden truths.

The climax erupts with a battle between Mother Mabel and Pierus. Mabel slays the Orchid King with Meirlach, liberating Zephyrus.

However, she then turns on him, fearing his hold over the Abbey’s women. Brielle intervenes and is accidentally impaled.

In grief, Zephyrus begs Mabel to help save her. In a ritual of blood and divine power, they resurrect Brielle.

But she awakens with her memories erased, told she was attacked by a bear.

Back at the Abbey, Brielle is haunted by inconsistencies. Her conversations with Harper reveal mutual memory gaps.

Her journal points to a lost love and a forgotten ordeal. When a fair folk woman confirms her involvement in the tithe, Mabel intervenes, warning her not to trust outsiders.

Eventually, Brielle demands the truth. Mabel confesses to erasing their memories to protect them from trauma.

Brielle, determined to choose her path, renounces her religious advancement and leaves Thornbrook.

As she departs, she sees a man watching her from the trees. Recognizing something unspoken, she follows him.

The man is Zephyrus. In a flood of returning memories and emotion, they reunite.

He reveals he gave up his godhood to save her. She, in turn, admits she could never let him go.

They embrace, not as god and mortal, but as equals. In the epilogue, Zephyrus fumbles a marriage proposal.

Brielle, ever changed and assertive, proposes instead. He accepts, and they begin a life built not on duty or divine design, but on shared love and chosen destiny.

Characters

Brielle

Brielle is the emotional and thematic heart of The West Wind, a young novitiate whose journey begins with strict devotion to the doctrines of Thornbrook Abbey but evolves into one of self-realization, defiance, and personal truth. At the outset, Brielle is shaped by her desire to be seen and acknowledged, striving for the esteemed role of acolyte within a rigid, hierarchical religious institution.

Her rescue of the wounded Zephyrus, in violation of the Abbey’s foundational rules, marks the beginning of her transformation. What begins as an act of quiet rebellion driven by compassion steadily grows into a series of choices that challenge the very bedrock of her beliefs.

As she journeys into Under, a strange and dangerous realm of fair folk and divine beings, Brielle is thrust into increasingly surreal and morally ambiguous situations. These trials strip away the certainties that once defined her.

Despite facing betrayal, physical punishment, and profound spiritual disillusionment, Brielle’s core strength lies in her willingness to keep searching—for truth, for love, and for her own agency. Her evolving relationship with Zephyrus, initially built on secrecy and mistrust, grows into a symbol of mutual sacrifice and recognition.

Even when memories of him are erased, her soul retains an echo of their bond, underscoring the profound emotional threads that tie her identity to love and defiance.

Brielle’s final decisions—choosing to leave Thornbrook, rejecting a life of dogma, and embracing a future forged by her own hand—demonstrate the full arc of her development. No longer the obedient novitiate longing for approval, she emerges as a woman capable of seeing through illusions, challenging power, and trusting in the messy, painful, and redemptive nature of human love.

Her journey is one of liberation, hard-earned through suffering and marked by an unwavering commitment to moral clarity, even in a world cloaked in ambiguity.

Zephyrus

Zephyrus, the titular West Wind, is a character woven from contradiction—divine and mortal, powerful and bound, self-serving and sacrificial. At first introduced as a mysterious, wounded man, his reluctance to reveal his true nature mirrors the guardedness that defines much of his early relationship with Brielle.

His charm, cryptic warnings, and emotional distance cast him as both a guide and a possible danger, especially as his ties to the shadow realm of Under deepen and grow more unsettling. Though he denies being fair folk, his actions and the magical world he moves through betray a far more complicated origin, which is later revealed when Lissi exposes him as a banished god.

Throughout The West Wind, Zephyrus oscillates between being a figure of temptation and one of redemption. His early manipulations—particularly regarding the quest for the god-forged sword Meirlach—fracture his bond with Brielle, nearly destroying what fragile trust they’ve built.

Yet it is through his remorse, his confession, and ultimately his sacrifices that he begins to emerge as more than a tragic immortal. He willingly gives up his godhood to save Brielle, a profound gesture that reorients his arc from divine detachment to deeply human love.

His torment under Pierus, his endurance of Under’s parasitic hunger, and his final transformation into a mortal man all serve to strip away the grandeur of godhood, leaving only the purity of his devotion.

By the end of the novel, Zephyrus has not only been physically broken but emotionally reborn. His reunion with Brielle, devoid of powers or expectations, affirms his longing not for worship or power but for partnership.

His arc is one of self-deconstruction—a former god learning what it means to be human, to be loved, and to live free from divine design.

Mother Mabel

Mother Mabel is a figure of immense influence and contradiction within The West Wind, a woman who straddles the line between oppressive authority and deeply wounded survivor. As the head of Thornbrook Abbey, she appears initially as a symbol of divine order, a strict enforcer of rules who serves as both an obstacle and gatekeeper to Brielle’s ambitions.

Her favor is a coveted blessing, and her disfavor a spiritual death sentence. Yet, Mabel’s harshness masks a tragic history—revealed only late in the story—that reshapes the reader’s understanding of her actions.

A survivor of seven years in Under, Mabel’s stoicism is born of deep trauma. Her failure to retrieve Meirlach and her survival through torturous magic explain, if not excuse, her obsessive control over the Abbey and its daughters.

Her willingness to erase Brielle and Harper’s memories after mistakenly stabbing Brielle reveals both a fear of her own fallibility and a twisted desire to protect the girls from truths she herself could not bear. This instinct to overwrite reality in the name of spiritual safety paints her as both a guardian and a tyrant.

Mabel’s eventual confrontation with Pierus, and her triumphant slaying of the Orchid King, reveals a woman capable of immense courage and strength. But her subsequent attack on Zephyrus and near-murder of Brielle complicate that image, framing her as a tragic villain whose trauma-driven rigidity blinds her to the consequences of her actions.

Her eventual participation in Brielle’s resurrection redeems her in part, but not fully. Mabel is not a character of easy resolution—she embodies the dangers of unchecked authority and the thin line between protection and control.

Harper

Harper begins as Brielle’s adversary, a cruel and competitive novitiate who taunts her about her appearance, social isolation, and lack of recognition. In the early chapters of The West Wind, Harper represents everything Brielle resents: favoritism, superficial beauty, and the cutthroat rivalry bred within the Abbey’s narrow hierarchy.

Yet, as the story progresses, Harper undergoes a striking transformation that reflects one of the novel’s most poignant arcs—how bitterness can evolve into empathy, and enemies into allies.

Initially, Harper’s barbed words and superiority make her a clear antagonist. However, once both girls journey into Under and return changed, their dynamic begins to shift.

Harper’s remorse for past behavior, coupled with her open vulnerability and apology, signals the beginning of a new phase in their relationship. Her comfort of Brielle after Zephyrus’s betrayal, and her honest account of being manipulated herself, help dissolve years of antagonism.

This evolution is one of mutual recognition—both women begin to see each other as complex individuals shaped by pain, competition, and shared struggle.

Harper’s acceptance of the acolyte role, while Brielle declines it, underscores their diverging paths. Yet, this does not reignite rivalry.

Instead, Harper’s visit to Brielle’s forge to make amends marks a sincere act of bridge-building. By the end of the novel, Harper is no longer a foil to Brielle, but a mirror—another young woman grappling with identity, spirituality, and power in a world that pits them against each other.

Her character speaks to the novel’s deeper commentary on internalized conflict among women and the healing power of humility and dialogue.

Pierus, the Orchid King

Pierus is a figure of corrupted divinity, the primary antagonist who represents the seductive and sadistic forces of Under. As the Orchid King, he presides over rituals of pain and pleasure with a detached cruelty that marks him as a symbol of patriarchal control cloaked in sensual beauty.

His power is absolute within his realm, and his subjugation of Zephyrus—piercing and feeding upon him in a grotesque ceremony—illustrates his need to dominate and debase others to assert his divinity.

In The West Wind, Pierus’s presence is both terrifying and mesmerizing. He embodies the extremes of Under’s morality: a place where boundaries blur, and where beauty masks predation.

His relationship with Zephyrus is not merely antagonistic but parasitic—he sustains himself by exploiting the West Wind’s essence. This dynamic draws a stark contrast between divinity and monstrosity, and exposes the cost of power when it exists without compassion or restraint.

Pierus’s death at the hands of Mother Mabel is not just a narrative climax but a symbolic exorcism. His defeat signals the collapse of Under’s old order and the breaking of the cycle of violence and submission.

Yet, his legacy lingers—in Zephyrus’s scars, in Brielle’s trauma, and in the question of what kind of power replaces the old. Pierus functions less as a complex character and more as a mythic antagonist, a necessary evil that forces others to confront their inner strength and moral clarity.

Lissi

Lissi, the sprite who inhabits Under’s more liminal spaces, acts as both a trickster and a truth-teller. Small in stature but significant in narrative weight, Lissi serves as a reluctant ally to Brielle.

Her demeanor is sardonic, her loyalty slippery, yet her role is essential in peeling back the layers of deception surrounding Zephyrus and the workings of Under.

Lissi reveals key truths—most notably Zephyrus’s identity as a god and the grotesque reality of his subjugation by Pierus. Her cynicism toward mortals and gods alike is rooted in survival and disillusionment.

Though she warns Brielle not to trust Zephyrus, her actions are not purely antagonistic. When Brielle later returns to Under to save Zephyrus, Lissi reluctantly aids her once more, proving that her jaded worldview has not entirely extinguished her capacity for compassion.

What makes Lissi memorable in The West Wind is her refusal to fit into neat categories. She is neither friend nor foe, divine nor human, but something else entirely—a witness to suffering who does not flinch, and a creature who, despite her resistance, acts when it matters most.

Her bargain for the sacred Text is a transaction born not of malice but necessity, reinforcing the novel’s recurring theme that even in the darkest realms, morality is rarely black and white.

Themes

Faith and Institutional Control

In The West Wind, the Abbey of Thornbrook serves as both a sanctuary and a prison, a sacred institution that espouses piety but thrives on dogmatic rigidity. Brielle’s experience within its stone walls reveals how organized religion can sometimes morph into an authoritarian system where obedience is valued over personal discernment.

Mother Mabel, as the figurehead of this institution, exemplifies the paradoxes of spiritual leadership—she is wise and resilient, yet also manipulative and secretive. The Abbey demands unwavering loyalty and suppresses dissent or deviation, as evidenced by its harsh punishments and the pressure Brielle faces to conform to its expectations.

The lashes she receives for her unexplained absence, the secrecy about Under, and the political competition for acolyte status all contribute to an environment where faith becomes entangled with control. Even divine elements are gatekept and mediated through a rigid hierarchy.

Brielle’s internal battle is not against her belief in the divine but against an institution that treats piety as performance. Her final decision to reject the acolyte path and leave Thornbrook underscores the idea that true spiritual awakening often requires disentangling oneself from institutional dogma.

Faith, the book suggests, should be an act of personal conviction, not a cage constructed by those in power. The Abbey’s control over the narratives of its members—even erasing their memories—underscores the extent to which institutional religion can manipulate truth in service of maintaining order and obedience.

Autonomy and the Pursuit of Identity

Brielle’s journey throughout The West Wind is deeply rooted in her search for autonomy and self-definition. From the very beginning, she is positioned as someone caught between who she is and who she is expected to be.

At Thornbrook, her identity is shaped by her status as a novitiate, defined by religious expectation and the ever-present goal of becoming an acolyte. Yet, even after years of dedication, she remains unchosen, her individuality diminished by rules and rigid roles.

It is only when she steps into Under—a space both lawless and unnervingly seductive—that she begins to question these boundaries. The rules of Under are different, emphasizing instinct, desire, and power.

Here, Brielle is forced to make decisions without institutional guidance. Each choice—whether to trust Zephyrus, to resist temptations, to seek answers from Willow, or to confront her fears—becomes a declaration of her agency.

The climax of her journey comes when she refuses the acolyte position not out of rebellion but out of clarity that the role no longer aligns with her identity. Her memory loss and subsequent rediscovery of self through scattered clues and emotional resonance mark her transformation.

No longer a woman shaped by duty or manipulation, she reclaims her agency by piecing together her past, challenging authority, and forging a new path. Identity, in this narrative, is not something inherited or bestowed—it is something reclaimed, wrested back from the hands of others, and shaped through acts of personal courage and conscious choice.

Power, Consent, and Bodily Sovereignty

The narrative explores multiple layers of power dynamics—physical, spiritual, and emotional—and how they relate to consent and sovereignty over one’s body and choices. Brielle’s body becomes a site of conflict: punished by the Abbey, violated in memory by institutional erasure, and ultimately sacrificed in her defense of Zephyrus.

At the same time, Zephyrus’s own body is used as a battery to power Under, his divinity commodified and harvested without his consent. These mirrored violations draw attention to how control is exercised over the body, particularly when tied to systems of belief or magical obligation.

Pierus, the Orchid King, embodies the most grotesque abuse of power—forcing rituals of consumption and submission upon Zephyrus and Brielle as a demonstration of dominion. In contrast, Brielle’s eventual choices reflect a reclamation of bodily autonomy: she chooses to fight the Stallion for Meirlach, to save Zephyrus despite warnings, and to reject divine roles imposed on her.

Even her emotional decisions—like pushing Zephyrus away, forgiving Harper, or proposing marriage—are framed as acts of personal agency rather than passive responses. The theme interrogates what it means to truly own one’s body and decisions in worlds where others constantly try to possess or define them.

Through Brielle and Zephyrus, the story critiques the systems—both divine and human—that exploit bodies for their ends and honors the struggle to reclaim them as vessels of personal will.

Memory, Trauma, and the Reconstruction of Truth

Memory plays a vital role in The West Wind, especially in how it intersects with trauma and the search for truth. When Brielle awakens after her near-death experience without any recollection of Zephyrus or the events in Under, she is unmoored, haunted by a sense of incompleteness.

This erasure of memory is not accidental—it is a deliberate act by Mother Mabel to protect and control. By manipulating Brielle’s recollections, Mabel tries to sanitize a traumatic event, shaping a palatable version of reality that aligns with the Abbey’s narrative.

But memory, even fragmented, refuses to be silenced. Clues resurface in Brielle’s journal, in conversations with Harper, in her emotional reactions to the world around her.

Trauma, rather than destroying her, becomes a trigger for awakening. It compels her to question, to investigate, and ultimately to recover a version of the past that had been stolen from her.

The process of reconstructing her memory becomes an act of rebellion and healing. It allows her to confront what was done to her and what she willingly endured.

In doing so, the narrative underscores that truth is not always what is presented, especially when institutions or powerful figures benefit from concealment. Remembering becomes a political act, a form of liberation from imposed narratives.

Through this theme, the novel honors the slow, painful process of confronting one’s past and the strength it takes to reclaim what has been buried, denied, or forcibly taken.

Love, Sacrifice, and the Choice of Humanity

At the core of The West Wind lies a love story defined not by destiny or divine design but by the hard choices and personal sacrifices of two flawed beings. Zephyrus and Brielle’s relationship begins with secrecy and grows through shared vulnerability, betrayal, and forgiveness.

What makes their bond so compelling is that it is constantly challenged—by power imbalances, personal ambition, and deep emotional wounds. Zephyrus begins as an enigma, a god stripped of full agency, and ends as a mortal man who has chosen love over divinity.

Brielle begins as a loyal servant of faith and transforms into a woman who defies godhood to rescue someone she loves. Their journey reflects a love that is not fated but forged through hardship.

It is not only romantic but also deeply existential. When Zephyrus gives up his godhood to save Brielle, and when she risks everything to rescue him from the parasitic vines of Under, these acts represent more than affection—they symbolize a shared belief that love is only real when chosen freely.

Their final reunion is marked not by grand mythic closure but by mutual recognition of sacrifice and consent. Even the botched proposal, turned on its head by Brielle, highlights that their love is no longer defined by tradition or divine plan—it is something they author together.

The theme celebrates the power of love not as an inevitability but as a radical, human decision made in the face of pain, uncertainty, and loss.