Toto by A. J. Hackwith Summary, Characters and Themes

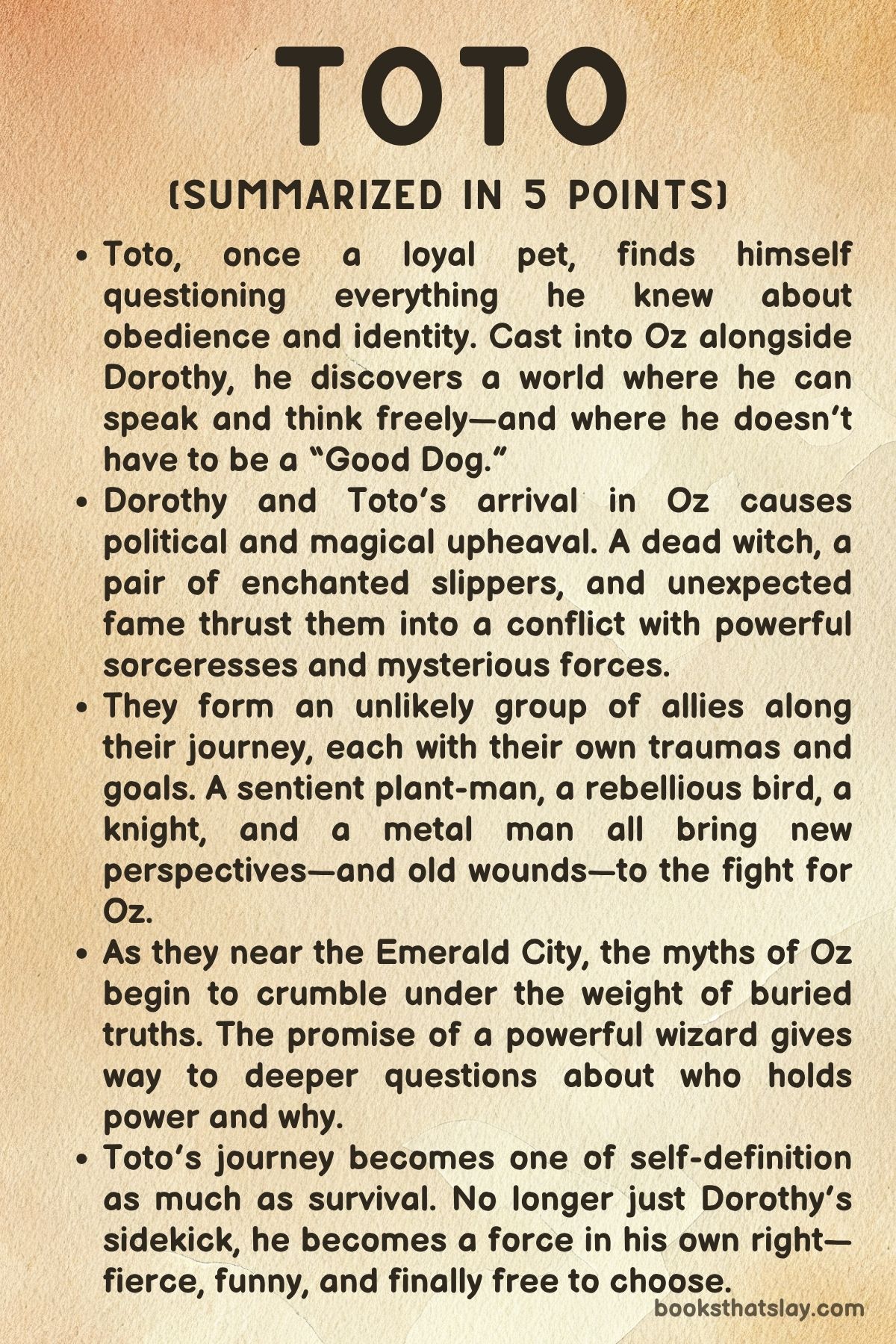

Toto by A. J. Hackwith is a daring and darkly comic reimagining of The Wizard of Oz, told from the sardonic, sharp-eyed perspective of Toto, Dorothy’s dog. Far from a loyal sidekick, Toto is a sentient narrator wrestling with betrayal, moral ambiguity, and the complexities of power.

This version of Oz is no bright and simple fantasy; it’s a fractured realm of deceitful authority figures, revolutionaries with questionable ethics, and magic systems loaded with social commentary. With irreverent wit and biting insight, Toto transforms a familiar story into a philosophical journey through rebellion, loyalty, and the painful evolution of self-awareness.

Summary

Toto’s story begins not with a whimsical journey, but with betrayal. After biting a neighbor in defense of Dorothy, he’s handed over to animal control by the people he thought were his family.

This fracture shatters his self-perception as a “Good Dog,” introducing a recurring emotional wound that frames his cynical voice throughout. Shortly after, a tornado strikes and transports him, Dorothy, and their Kansas home into the bizarre land of Oz.

Oz, from Toto’s eyes, is not just surreal—it’s sinister. The Munchkins’ suspiciously cheerful demeanor unsettles him, especially when layered with vague political undertones.

Glinda’s entrance in a bubble, her labeling of Dorothy as a witch killer, and her bestowal of silver slippers don’t read as whimsical gestures to Toto—they resemble rites in a magical power hierarchy. The appearance of the Wicked Witch of the West and her challenge to Dorothy further convinces Toto that they’ve stumbled into a cold war between elite magical factions, and Dorothy has unwittingly become a pawn.

The trio’s journey to the Emerald City begins with this unease already festering. When they encounter a living Scarecrow hanging from a post, Toto is more alarmed than curious.

Dorothy insists on rescuing the Scarecrow, who turns out to be unsettlingly humanlike and clearly altered by dark enchantment. Alongside him is Crow, a flamboyant blue bird who insists he’s a crow, not a jay.

Crow’s revolutionary fervor and exaggerated storytelling add ideological chaos to the group. Toto, mistrustful and sardonic, becomes the reluctant center of this growing entourage.

The group barely survives an assault by sentient trees, which reinforces the constant danger of Oz’s wilderness. After a near-fatal fall down an embankment, Dorothy and Toto come across a rusted metal man with an axe.

He is revived by Dorothy but attacks in confusion, nearly killing Toto. He is soon revealed to be Chopper, a Munchkin blacksmith transformed into a mechanical golem by the cult-like Tartpatch Gang.

His sister, Lettie, arrives to explain her desperate efforts to restore his humanity. Her struggle introduces themes of identity lost to ideology and the corruption of kindness by manipulation.

The group reconvenes, but the forest shifts, splitting Toto and Crow from the others. They are drafted into a rebellion of birds fighting against Barth, a tyrannical tiger king.

Crow praises Toto as a legendary strategist, thrusting him into a farcical leadership role. The rebellion’s tactics and ethics are questionable, and Toto watches the line between liberation and cruelty blur.

In the climax, Toto manages to defeat Barth, only to see the rebels replace one despot with a listless cousin, highlighting how revolutions may not birth justice—just new rulers.

Toto’s inner conflict intensifies. Though he postures as uncaring, his thoughts often return to Dorothy.

Crow’s radical optimism clashes with Toto’s growing wariness of all systems—whether imposed by oppressors or rebels. When the group finally reaches the Emerald City, the contradictions of Oz become unignorable.

While the city dazzles with spectacle, it thrives by extracting magical resources from surrounding lands, leaving ecological and societal decay in its wake.

The Wizard himself is a fraudulent tech guru in Earth clothes—disconnected from the world he exploits. He offers reductive answers to the group’s quests for courage, brains, and heart, exposing his hollowness.

When Dorothy refuses his manipulative “gifts,” the Wizard retaliates, sending them on a new mission: kill the Witch of the West and bring back her broomstick. The group’s fall from grace within the city marks a critical turning point—Oz’s grand promises collapse under the weight of its hollow core.

As they move toward the Witch’s territory, their unity falters. Lion attempts to leave, but Dorothy’s plea keeps him grounded.

In a rare moment of vulnerability, the group confesses their fears and failures, binding them again, if temporarily. But soon, they’re ambushed by monstrous stone Rooks.

Dorothy is abducted, and Toto finds himself imprisoned at the Witch’s fortress.

Inside, he meets Min, a gentle Rook guard who offers compassion and reveals more of Oz’s buried truths. The Rooks, once radiant beings with gemstone markings, were deformed by a plague unleashed during the Wizard’s reckless mining.

Their homeland was destroyed, and their history erased. Min and Toto develop an unexpected alliance, grounded in shared grief and disillusionment.

Meanwhile, Dorothy delays the Witch by feigning knowledge of a mythical sword, giving her friends time to act.

With Min’s help, Toto escapes and reconnects with Crow. They learn that Min harbors dreams of killing the Wizard herself.

Her people’s suffering, mirrored by the corrupted land and fractured societies of Oz, exposes the Wizard as the true villain. The group infiltrates the Wizard’s sanctum, discovering the Mother Opal—an ancient gem holding ancestral imprints and potentially a cure for the Rooks.

When Min touches it, her affliction briefly reverses, giving hope and urgency to their mission.

Dorothy confronts the Wizard with the broom, only to be manipulated again. Min’s fury bursts forth, and the group attempts to stop the Wizard’s escape via drone.

A chaotic battle ensues inside the craft. In a moment of courage and grief, Crow sacrifices himself to shield Dorothy from a lethal magical strike launched by Glinda, who reveals herself as a final antagonist driven by greed and control.

In the climax, Min’s sabotage ensures the stolen opal reaches safety. Evaline—the Witch of the West—returns and traps Glinda, neutralizing her threat.

The revolution does not end in triumph, but in a fragile rebalancing. Scarecrow becomes the interim governor, Min works to rebuild her people’s legacy, and the group grieves Crow’s loss.

Dorothy prepares to return home. Toto, once eager for freedom from duty, chooses to remain in Oz, drawn to its unfinished business and the friends who need him.

The closing note is not of triumph but of transformation. Loyalty, pain, and choice reframe the idea of home—not as a place, but a commitment to protect and belong.

Through Toto’s evolution, Toto becomes a story not about escaping fantasy but about confronting it, reshaping it, and choosing to stand where it matters most.

Characters

Toto

Toto is the sardonic, emotionally scarred terrier at the heart of Toto by A. J.

Hackwith. His voice frames the entire narrative, transforming what could have been a whimsical adventure into a deeply introspective journey about loyalty, betrayal, and the burdens of sentience.

At the start, Toto’s identity crisis is rooted in a personal betrayal—his family’s decision to hand him over to animal control. This act shatters his image of himself as a “Good Dog,” creating a fracture that drives his cynicism throughout the story.

As the journey in Oz unfolds, Toto becomes both guide and commentator, dissecting the surreal environment with biting wit and wary skepticism. His protective instincts never quite leave him, especially regarding Dorothy, but he wrestles with the emotional dissonance of still caring for someone who abandoned him.

Toto’s evolution is marked by a reluctant embrace of heroism, resistance against oppressive systems, and ultimately a complex understanding that being “bad” in a broken world may be the truest form of goodness. His decision to remain in Oz at the end is not just a personal liberation, but a conscious choice to fight for a land that mirrors his own fragmented but fiercely loyal self.

Dorothy

Dorothy is reimagined in this version as a practical, compassionate, and emotionally resilient young woman who serves as Toto’s moral compass and narrative foil. Though the betrayal at the story’s beginning causes a rupture in their bond, Dorothy never loses her protective instincts or her optimism.

She consistently believes in helping others—even when it places her at risk—and her compassion manifests in moments like reactivating Chopper and trusting Min. Despite the manipulations she endures at the hands of the Wizard and Glinda, Dorothy clings to her moral clarity, challenging authority and refusing to accept easy answers.

Her deepening relationship with Toto adds emotional richness, culminating in a quietly powerful revelation that she has always understood him, even when he doubted her. Dorothy’s journey through Oz is both external and internal; she grows not just as a leader of the group, but as a young woman navigating systemic corruption with empathy and courage.

Her invitation to Evaline to join her on Earth signals a widening worldview, one that embraces difference, redemption, and ongoing resistance.

Crow

Crow is an anarchic burst of flamboyance, chaos, and radical ideology whose presence electrifies every scene he enters. A blue jay who insists on being called a crow, his identity is a deliberate subversion of expectations, just like his politics.

He champions rebellion for its own sake, spinning grand narratives about resistance, revolution, and overthrowing tyrants—many of which are more theatrical than practical. Crow’s charisma masks a profound vulnerability, especially in his loyalty to Toto and his eventual sacrifice during Glinda’s ambush.

While his antics often blur the line between genuine revolution and performative heroism, his final moments reveal the depth of his commitment. By crashing into Glinda’s magical attack to save Dorothy, Crow proves that even the loudest, most chaotic voices in a revolution can act with deep conviction.

His death is a shattering moment, forcing the group—and especially Toto—to reckon with the cost of rebellion and the heartbreak of losing a friend who was more than just comic relief.

Scarecrow

Scarecrow is a haunting presence, not the lighthearted companion from earlier Oz tales but a darkly reimagined creature shaped by necromancy and loss. His origin story and behavior imply a transformation not born of whimsy but of corruption and magic gone awry.

Scarecrow’s intelligence and eloquence are tempered by bouts of silence and existential dread, especially in moments of trauma like the ambush by the Rooks. He is deeply affected by violence and haunted by the inhumanity he senses in himself.

Despite these inner demons, Scarecrow proves to be a wise and compassionate companion, forming strong bonds with the group and serving as an emotional stabilizer, particularly for Toto. His ascension to provisional governor at the end of the story marks a poignant evolution—from a creature made to hang and rot to one trusted with rebuilding a fractured world.

His journey captures the tension between constructed identity and self-actualization, echoing the book’s central theme that true wisdom lies in acknowledging and embracing one’s broken parts.

Chopper

Chopper is one of the most tragic figures in Toto, a once-kind blacksmith turned into a mindless, axe-wielding tin golem by the Tartpatch Gang. His transformation reflects a broader commentary on societal manipulation and the loss of agency under cult-like control.

Although initially terrifying, his reawakening by Dorothy and subsequent interactions with his sister Lettie reveal the emotional wreckage beneath his metal exterior. Chopper’s struggle to regain a semblance of his former self is both physical and symbolic—every swing of his axe and stutter of his voice a testament to the war between programming and memory.

His bond with Lettie and the other companions hints at a slow, painful healing process, but he never entirely recovers. Instead, Chopper stands as a living metaphor for those damaged by systemic indoctrination, carrying both immense strength and unhealed trauma.

Lettie (Violetta)

Lettie, the fierce and articulate Munchkin knight, subverts the stereotype of her people as quaint and harmless. As Chopper’s sister and caretaker, she embodies resilience, practicality, and quiet rage against the systems that destroyed her brother.

Her background with the Tartpatch Gang adds depth to her character, portraying her not just as a guardian but as someone who intimately understands the seductive pull of ideology. Lettie is deeply principled, willing to challenge even Dorothy and Toto when necessary, but she also shows vulnerability in her inability to fully “fix” her brother.

Her alliance with Dorothy is born from mutual respect rather than convenience, and she quickly becomes one of the most level-headed members of the group. Through Lettie, the story critiques the ease with which the marginalized are overlooked or stereotyped, even in a magical land.

Lion

Lion in this retelling is melancholic, sardonic, and disillusioned, a sovereign more interested in solitude than glory. As Barth’s cousin, he inherits a throne he neither wants nor believes in, embodying the dissonance between power and desire.

His depressive temperament and reluctance to engage in leadership are understandable given the brutal coronation and the parade of Barth’s mutilated form, which he quietly endures rather than celebrates. Lion’s strength lies in his introspection; he is acutely aware of the cyclical nature of power and violence.

Though he threatens to leave the group at one point, Dorothy’s plea brings him back, hinting at a latent nobility and commitment to justice. He remains a quiet presence but one that adds emotional ballast to the group, a reminder that courage often takes the form of choosing to stay even when everything inside urges retreat.

Min

Min, the gentle Rook guard, becomes a revelation in the final act of Toto. At first glance, she appears meek and obedient, but as her backstory unfolds, she emerges as one of the most quietly revolutionary characters in the novel.

A survivor of the Rook blight caused by the Wizard’s exploitative mining, Min’s arc is one of reclaimed agency and ancestral healing. Her interaction with the Mother Opal and her choice to smuggle fragments back to her people signal a rebirth of Rook identity.

Her partnership with Toto, grounded in mutual respect and shared trauma, adds another layer to Toto’s evolving understanding of loyalty. Min’s final confrontation with the Wizard is not just cathartic but symbolic, representing the silenced rising to confront their oppressors with truth and courage.

By the end, Min stands as a figure of hope—quiet, firm, and unyielding in her pursuit of justice.

The Wizard

The Wizard is a hollow, self-serving charlatan whose presence shatters the myth of benevolent authority in Oz. Portrayed as a tech-bro masquerading as a mystical savior, his arrogance and emotional detachment expose the story’s core themes of manipulation and false heroism.

He offers transactional solutions that trivialize the emotional and psychological needs of Dorothy’s companions, revealing an ideology grounded in control rather than compassion. His true villainy lies in his exploitation of the Rooks and his willingness to rewrite history to maintain power.

Even when cornered, he clings to rhetorical deflection and manipulation, never truly admitting fault. His ultimate failure is not just political but existential—he cannot imagine a world in which he is not worshipped or in control.

His demise comes not as a grand fall but as a rejection by the very people he tried to dominate.

Glinda

Glinda undergoes one of the most shocking character transformations in the novel, evolving from benevolent guide to final antagonist. Her initial charm and regal aura mask a deep hunger for control, revealed only at the climax when she seizes the opportunity to claim the shoes and power for herself.

Her betrayal cuts deeply, particularly because she manipulates Dorothy under the guise of mentorship. Glinda’s true nature—a practitioner of magical feudalism who sees allies as pawns—serves as a mirror to the Wizard’s authoritarianism.

Her entrapment inside a magical bauble by Evaline is not just a plot twist but a symbolic reckoning, suggesting that even the most polished, well-spoken leaders must be held accountable for the systems they perpetuate. In Glinda, the book finds its most chilling commentary on the seductive nature of seemingly benevolent authority.

Evaline (The Witch of the West)

Evaline’s presence in Toto is a powerful inversion of her original archetype. Initially framed as the antagonist, she evolves into a nuanced figure of resistance, resilience, and truth-telling.

Her motivations are revealed to be far less malevolent than the propaganda suggests; she is not a tyrant, but a survivor pushing back against a colonial structure that has labeled her dangerous. Her alliance with Min and eventual rescue of the group at the climax reframes her as a necessary disruptor of entrenched power.

Evaline’s decision to join Dorothy on Earth at the end underscores the novel’s message of solidarity across boundaries and the importance of listening to those labeled as “monsters. ” She is not a witch to be feared, but a woman willing to burn everything down to protect what remains.

Themes

Betrayal and Disillusionment

Toto’s emotional journey begins with a profound act of betrayal: being handed over to animal control by Dorothy’s guardians. This foundational rupture in his sense of belonging and trust informs his entire psychological landscape throughout Toto.

He defines himself as a “Good Dog,” a concept loaded with moral simplicity and unconditional loyalty, and the moment that identity is shattered, his worldview begins to unravel. The act of betrayal isn’t isolated—it echoes across the fantastical world of Oz, where almost every institution and relationship is layered with deception, manipulation, or hidden agendas.

From the eerie performativity of the Munchkins’ utopia to Glinda’s coercive benevolence, Toto perceives his surroundings as treacherous. What begins as a personal betrayal expands into a thematic exploration of systemic disillusionment.

The Wizard, revealed to be a hollow figure of power wrapped in technological arrogance, embodies institutional betrayal at a societal level. He promises salvation and meaning but delivers condescension and exploitation.

Even supposed revolutions, like the bird rebellion, succumb to the same patterns of cruelty and corruption as the regimes they overthrow. Toto’s growing cynicism, born from an initial wound, is constantly validated by the layers of betrayal around him.

This thread reaches its peak in Glinda’s final revelation as a power-hungry manipulator, and in Toto’s painful realization that heroism, revolution, and even friendship are susceptible to compromise. Betrayal, then, is not just an inciting incident but the lens through which Toto learns to navigate the treacherous structures of loyalty, governance, and power.

Identity and Moral Complexity

Toto’s narrative is driven by a crisis of identity. Once tethered to the simplistic dichotomy of “Good Dog” versus “Bad Dog,” Toto is thrust into a world where those binaries no longer apply.

His betrayal shatters his moral compass, leaving him to reconstruct a sense of self in an environment that defies traditional notions of right and wrong. As he journeys through Oz, his sarcastic commentary masks a deeply introspective inquiry into his own ethics.

His actions often contradict his proclaimed cynicism—he protects Dorothy, guides Crow, questions authority, and even spares enemies when he could exact revenge. These inconsistencies aren’t flaws but representations of moral complexity.

Toto doesn’t reject goodness; he redefines it. His transformation is mirrored in other characters as well—Crow’s naive idealism collides with reality, Chopper’s metallic body becomes a metaphor for coerced transformation, and Min’s gentle resistance defies expectations of her monstrous appearance.

The characters are never wholly virtuous or villainous, reinforcing the idea that identity is not static but forged in response to systems of oppression and personal trauma. Toto’s final decision to remain in Oz, not as Dorothy’s pet but as an autonomous protector of a new world, signifies his acceptance of a complex, self-defined identity.

He no longer clings to the comfort of moral absolutes. Instead, he chooses a path that balances care with resistance, loyalty with autonomy—a blend that redefines what it means to be “good” in a broken world.

Corruption of Power and False Authority

Throughout Toto, the narrative repeatedly exposes the emptiness and danger of unearned authority. From Glinda’s glamorized manipulations to the Wizard’s techno-charlatanry, power is shown not as earned through wisdom or moral fortitude, but through performance, spectacle, and exploitation.

The Wizard, in particular, is a scathing caricature of technocratic dominance: he presents himself as a benevolent force while hoarding magical resources, exploiting native populations, and reducing individuals to metrics of utility. His gifts to the classic trio—brains, heart, courage—are recast as patronizing gimmicks rather than meaningful transformations.

The very architecture of Oz, from the hollow pomp of Emerald City to the militarized bird kingdom, reinforces how centralized power thrives on image and fear. Even the revolutionaries, like the bird rebels under Crow’s influence, become complicit in cycles of cruelty when they publicly mutilate their former oppressor.

The succession of power from one figure to another rarely brings justice—it simply reshuffles who wields control. Glinda’s final betrayal underscores this theme with brutal clarity: her genteel exterior hides a ruthless hunger for dominion.

The critique is neither subtle nor fantastical—it’s direct, political, and biting. Toto, initially eager to follow rules and respect order, becomes a reluctant revolutionary not because he idolizes chaos, but because the structures he once believed in have failed him utterly.

The message is clear: power without accountability is corrosive, and challenging it often requires those on the margins—talking dogs, flightless birds, grieving stone soldiers—to step into the vacuum and reshape the world.

Revolution and the Cost of Change

Rebellion in Toto is presented not as a cathartic triumph but as a messy, morally ambiguous process fraught with contradictions. The bird rebellion against Barth offers a microcosm of revolution’s dual nature—its necessity and its danger.

Toto is reluctantly cast as a symbol of resistance, despite his deep skepticism of ideology and his discomfort with hero worship. The rebellion succeeds, but the aftermath is unsettling: Barth is paraded as a broken trophy, and his melancholic cousin inherits a crown he does not want.

The revolution, in many ways, replaces one flawed regime with another. The idea that liberation can reproduce violence is further reinforced by the behavior of the victorious birds, whose performative justice echoes the cruelty of their oppressors.

Crow’s arc exemplifies the seductions and failures of revolutionary idealism. Initially full of slogans and passion, he is ultimately confronted with the harsh reality of loss, betrayal, and sacrifice.

His final act—sacrificing himself to save Dorothy—marks a shift from symbolic resistance to personal responsibility. Min’s quiet, purposeful resistance contrasts with the spectacle-driven rebellion, offering a more grounded vision of change rooted in care and community healing.

Toto’s evolution mirrors this complexity: he becomes a leader not by ambition but by necessity, learning that true change often requires compromise, grief, and uncelebrated labor. The narrative reframes revolution as a process, not a singular moment, where the end goal isn’t power but protection, restoration, and the courage to choose compassion over vengeance.

Home, Belonging, and Emotional Reclamation

Beneath the action and satire, Toto is ultimately a story about the search for home—not just as a physical place, but as an emotional truth. Toto’s journey begins with his violent removal from what he considered home, followed by a cascade of betrayals and moral reckonings that strip him of all comforting certainties.

Oz, with its surreal landscapes and unpredictable magic, is never truly home, but it becomes the setting where Toto redefines what belonging means. His relationship with Dorothy is central to this evolution.

Though hurt by her earlier betrayal, he never fully severs his emotional tether to her. Their moments of reconciliation—particularly when he learns she’s always understood him—are laden with the kind of emotional honesty that reorients Toto’s understanding of love and loyalty.

Similarly, his alliances with Crow, Min, and others represent chosen connections, not imposed roles. These relationships aren’t idealized; they are fraught, painful, and often tested.

But they are real. The choice Toto makes at the end—to stay in Oz, not as a sidekick but as an agent of his own purpose—marks a profound reclamation of agency and emotional truth.

He doesn’t return “home” in the traditional sense because he’s built a new one, forged through shared struggle, mutual care, and hard-won insight. In a world of shifting allegiances and uncertain futures, Toto’s sense of home becomes less about geography and more about emotional anchoring—those moments where love is chosen, not assumed, and where loyalty is born not of obedience, but of earned trust.