Vanishing Treasures Summary and Analysis

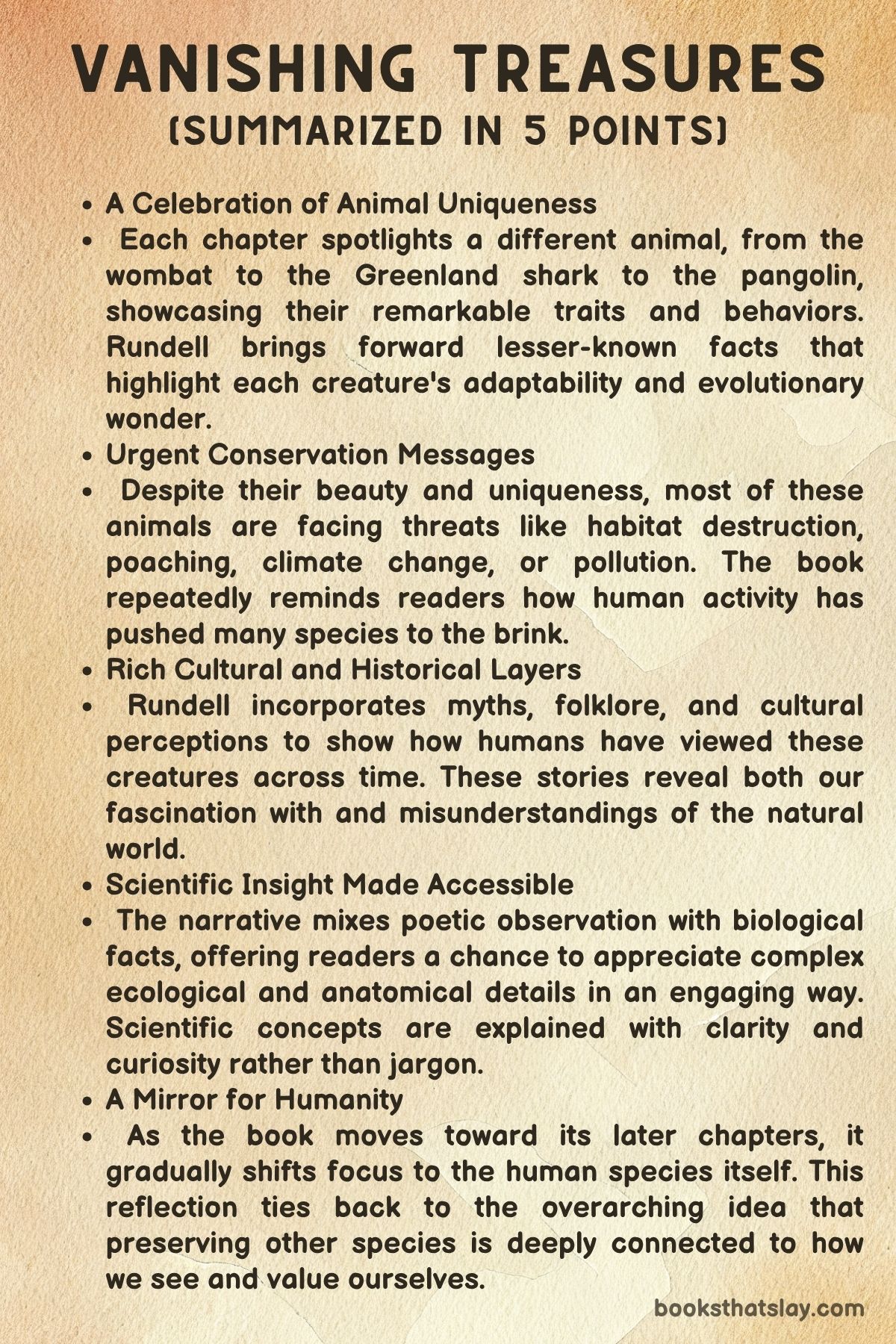

Katherine Rundell’s Vanishing Treasures is a lyrical and elegiac collection of essays that examines the mysterious beauty and imperiled status of some of the world’s most fascinating animals. With a blend of scientific precision and emotional depth, Rundell brings to light how human fascination, myth-making, and environmental destruction intersect across centuries and species.

From the speech-mimicking seal to the flame-colored bat, each chapter reflects on the strangeness of nature, our cultural interpretations of animals, and the urgent ecological crises that threaten their survival. This book invites readers not just to admire these creatures, but to mourn and protect what is steadily disappearing.

Summary

Vanishing Treasures opens with an examination of the wombat, whose docile appearance conceals remarkable physical power and defensive traits. Once beloved by Dante Gabriel Rossetti for its misleading charm, the wombat emerges as a creature of evolutionary brilliance—muscular, fast, and equipped with an upside-down pouch that helps it dig and nurture simultaneously.

Despite their intelligence and complex physiology, wombats were once hunted as pests, a fate that nearly wiped out certain species. While now legally protected, many still teeter on the brink of extinction, especially the rare northern hairy-nosed wombat.

The Greenland shark follows, an ancient and near-mythical animal that might live for over 400 years. One shark may have swum beneath the Arctic ice when Shakespeare was alive.

Blind and slow-moving, these sharks are marvels of endurance and longevity. But they too face threats from industrial overfishing, particularly for the luminous oil found in their livers.

Their late reproductive age means any decline in numbers could prove catastrophic. These creatures, ancient and almost ghostly, are framed as living monuments to endurance in a world that values speed and profit.

Raccoons appear next—symbols of contradiction. Highly intelligent and famously adaptable, they are capable of thriving in urban landscapes.

One raccoon even made it to the White House as a would-be meal for President Coolidge, only to become a beloved pet named Rebecca. But the raccoon’s cultural history is fraught.

The word “coon” became a racial slur rooted in 19th-century minstrelsy, attaching harmful stereotypes to an animal celebrated for its cleverness. In the essay, the raccoon becomes an emblem of how animals can be both adored and abused, symbolically and physically.

Their ability to survive in human-dominated spaces is remarkable, but it hides the losses of their rarer cousins, such as those from Barbados and Cozumel, now almost extinct.

The giraffe takes center stage as an animal that has long been perceived as otherworldly. From ancient misinterpretations to Parisian obsession in the 19th century, the giraffe has oscillated between icon and commodity.

Its unique anatomical features—an extraordinarily long neck, a deep blue tongue, and a vulnerable drinking posture—remain partly unexplained by modern science. Once symbols of prestige, giraffes are now poached for their skins and bones.

Their dwindling numbers echo a theme that runs throughout the book: admiration often leads to exploitation, and beauty can invite destruction.

Swifts, the aerial artists of the sky, live almost entirely in flight. They eat, sleep, and even mate on the wing, a feat enabled by their ability to sleep with one hemisphere of the brain at a time.

These birds are incredibly efficient and aerodynamic, yet they are threatened by the collapse of insect populations and the loss of nesting sites. Despite their seeming invincibility in the air, they are vulnerable.

Their decline is symbolic of a broader ecological imbalance. The swift’s flight becomes a visual metaphor for existence itself—constantly in motion, breathtaking, but now at risk of disappearing.

Lemurs, with their complex social structures and female-led groups, are portrayed as evolutionary anomalies in the best sense. Found only in Madagascar, lemurs once flourished, but now face existential threats from deforestation and hunting.

These creatures exhibit unique behaviors, from musical calls to scent-marking with elaborate rituals. Yet their habitat is vanishing, and with it, the cultural and biological heritage they represent.

Rundell paints them not as exotic curiosities, but as deeply social beings losing their ancestral homes.

Hermit crabs are introduced not as isolated misfits, but as symbols of cooperation and adaptability. Often seen dragging mismatched shells across the beach, these crabs actually participate in complex social negotiations over shell ownership.

When one outgrows its home, others line up to swap, forming a temporary communal effort. Their use of sea anemones as defense mechanisms and their ability to use trash as shelter speaks to their resourcefulness in a polluted world.

Hermit crabs show that survival in the Anthropocene requires ingenuity and flexibility, but also highlight the irony of creatures evolving to live in what humans discard.

The narrative then moves to Hoover, a harbor seal raised in Maine who astounded scientists by mimicking human speech. His story blurs the line between animal behavior and human imagination.

Seals, it turns out, are capable of complex vocalizations, often misinterpreted as ghostly cries in seafaring lore. Harp seals, particularly their maternal behavior, illustrate the brutal consequences of climate change: melting ice deprives pups of the time they need to nurse, leading to mass drownings.

This becomes a stark symbol of the immediacy of environmental collapse.

The world of pinnipeds expands into a dazzling gallery—elephant seals with their prodigious diving capacities, ribbon seals with their painted elegance, hooded seals with their inflatable sacs. Each species is a testament to evolutionary whimsy and functional genius.

But their lives are shrinking due to habitat destruction, warming waters, and human activity. The text renders each one not just as a zoological entry, but as a character with drama and vulnerability.

The selkie, a mythic creature torn between sea and shore, provides a mythological counterpoint. As a being forced to shed its skin and live among humans, the selkie embodies the sense of loss animals might feel when torn from their ecosystems.

This folkloric figure becomes a metaphor for captivity, domestication, and ecological grief. Like Hoover, the selkie represents the forced transformation of wildness into spectacle.

Bears then rise into view, straddling reverence and cruelty. Once believed to be shapeless blobs licked into form by their mothers, bears have been both adored and tortured throughout history.

From Pliny’s odd theories to Elizabethan bear-baiting and cosmetic use of bear fat, the contradictions abound. Romanticized by poets and massacred in practice, bears are caught in humanity’s shifting gaze.

Today, six of the eight bear species face extinction. Their story becomes a mirror for our conflicting desires to admire, possess, and annihilate.

In the final sections, the narrative shifts to creatures lesser known but no less emblematic. The stork is mythologized as a divine courier, bearing infants and messages through war and peace.

Their migration puzzled scientists for centuries until one was discovered in Germany with an African spear lodged in its neck—proof of its intercontinental journey. Storks, once hunted to extinction in parts of Europe, are now cautiously being reintroduced.

Spiders provoke fear and awe. Jumping spiders, with their hydraulic limbs and acute vision, become miniature marvels.

Spider silk’s strength and use in wartime optics underscore their overlooked utility. Yet spiders are feared globally and rarely protected.

Rare species disappear without notice.

Bats, long associated with darkness and fear, are actually diverse and ecologically critical. Echolocation, misunderstood for centuries, was finally proven through rigorous scientific inquiry.

Bats pollinate, consume pests, and maintain ecosystem balance. Still, they are threatened by habitat loss, superstition, and tourism.

Tuna, especially the bluefin, represent the tragedy of abundance exploited. Celebrated by Hemingway and hunted to near extinction, tuna are commodified to the point where extinction may mean profit.

Some corporations are already freezing bodies, speculating on future scarcity.

The golden mole closes the book—a nearly invisible creature that lives underground, iridescent and blind. Its shimmering coat and reclusive life embody the paradox of unnoticed beauty.

The mole stands as a final symbol: of life that exists beyond human recognition, and of the treasures we are letting slip away.

Throughout Vanishing Treasures, Rundell delivers a passionate appeal. These animals are not just biological oddities; they are stories, voices, and presences that challenge and enrich human understanding.

Without action, their stories will become elegies, their lives footnotes in our history of destruction.

Analysis of Themes

Human Fascination as Double-Edged Attention

Human curiosity toward animals in Vanishing Treasures is presented as a force capable of both wonder and ruin. Throughout the essays, Katherine Rundell highlights how our enchantment with animals has sparked myth, art, and science—but also destruction.

This tension is visible in the treatment of animals like giraffes and wombats, which were once revered in courtly circles and artistic circles but ultimately commodified. A giraffe becomes a symbol of royal novelty, its elegance reduced to a consumerist fascination that later justifies its hunting.

Similarly, the wombat is both muse and target, adored in Victorian parlors yet nearly exterminated due to misconceptions and agricultural hostility. The seal’s transformation into folklore figures such as selkies and the mythologizing of raccoons through racialized caricature further reflect the danger of projecting human narratives onto non-human lives.

These distortions elevate animals to the realm of symbolism while often erasing their ecological realities. Even Hoover the talking seal, a marvel of linguistic mimicry, is caught between admiration and spectacle.

Human fascination, then, becomes a double-edged attention—an impulse that can generate care, legislation, and conservation, or morph into misrepresentation, commercial exploitation, and negligence. Rundell suggests that while love can preserve, unchecked awe can distort.

The act of noticing, she implies, must evolve beyond enchantment into responsible empathy, or else we risk turning living marvels into fading stories.

The Fragility of Adaptation

Many of the creatures profiled exhibit extraordinary evolutionary traits, but Vanishing Treasures reveals how these adaptations, though impressive, are fragile under anthropogenic pressures. The Greenland shark has survived centuries, its metabolism so slow it is practically frozen in time, yet this ancient longevity is easily disrupted by modern fishing practices.

The swift, a marvel of aerial design, survives almost entirely in flight, yet cannot withstand habitat collapse or pesticide-induced insect loss. Lemurs, complex in their matriarchal social systems and honed by millennia of geographic isolation, find themselves powerless against deforestation.

These species are not failing because they are unfit, but because the environment to which they were perfectly adapted is being irreversibly altered. Even the hermit crab, whose ingenuity lies in communal shell exchange and improvisation, is being pushed to inhabit plastic refuse due to ocean pollution.

The text shows that evolution does not promise permanence; it is a response to conditions that are no longer stable. Rundell’s essays emphasize that adaptation, while a testament to nature’s ingenuity, cannot keep pace with the rapidity and scale of human-induced change.

The underlying suggestion is that survival traits are only as useful as the ecosystem that allows them to function. In the modern world, resilience is insufficient without sanctuary.

Commodification of Wildness

Across species, Vanishing Treasures scrutinizes the commodification of wildness—how animals are transformed into products, metaphors, or sources of human gain. Bluefin tuna, prized for their speed and stamina, are industrially harvested to the brink of extinction, not for sustenance but for luxury and speculative investment.

Raccoons are manipulated into mascots or slurs, their identities fragmented across cultural and racial discourses. Bears are farmed for bile, seals killed for pelts, and spiders exploited for military use.

Even more symbolically, golden moles and their beauty—accidental, unseen, and iridescent—highlight how commercial value often only emerges at the edge of extinction. Rundell argues that wildness is often admired only when it serves a human function—whether in war, myth, medicine, or aesthetic inspiration.

Animals become vessels for human fantasies, their ecological roles diminished in favor of symbolic ones. This theme underscores the transactional lens through which we view nature: as either threat, tool, or treasure.

Commodification is not limited to economic activity—it includes linguistic appropriation, scientific exploitation, and artistic co-option. Through lyrical yet biting observation, Rundell presses the urgency of recognizing animals not for their use but for their own sake, advocating for a paradigm shift from ownership to kinship.

Ecological Memory and Amnesia

Vanishing Treasures operates as a catalog of ecological memory, restoring forgotten histories of animals that once lived abundantly or in closer communion with humans. From the arrow-struck stork that helped scientists trace migratory routes to the overlooked intelligence of jumping spiders, Rundell reveals how much of nature’s story remains hidden or misunderstood.

Yet this act of remembrance is haunted by amnesia. Animals like the Cozumel raccoon or monk seals exist as flickers in memory and myth, often only rediscovered when they are nearly gone.

The essays reveal how quickly cultural and biological knowledge is lost—swifts vanish from skylines before their mating rituals are even understood, and hermit crabs adopt garbage in lieu of ancestral shell systems without our notice. Rundell laments not only the extinction of species, but the extinction of awareness.

She draws parallels between folkloric erasure and biological disappearance, suggesting that both are symptoms of a deeper cognitive loss. In retelling these stories, the book itself becomes a form of resistance to forgetting, an attempt to keep alive what the modern world seems determined to dismiss.

By pairing natural history with poetic resonance, Rundell rekindles a sense of continuity, urging readers to restore a broken lineage between human beings and the rest of life on Earth.

Myth and Science as Co-narrators

Rather than treating myth and science as opposing forces, Vanishing Treasures presents them as twin modes of engagement with the natural world. The seal, for instance, is both a subject of scientific study and a selkie of folklore.

Rundell treats Hoover’s mimicry not only as a neurobiological feat but also as a modern incarnation of ancient sea legends. Similarly, the stork exists as both migratory bird and magical courier of infants, while the bat toggles between echolocating marvel and Dracula’s familiar.

This dual narrative structure allows readers to appreciate that human understanding is not purely empirical or poetic—it is both. By using myth to humanize animals and science to affirm their reality, Rundell challenges the reader to value animals as more than data points or symbols.

She shows that myths, though factually incorrect, often arise from deep attention and shared cultural recognition of an animal’s mystery. Conversely, scientific observation, while grounded in evidence, is not devoid of wonder.

In framing myth and science as co-narrators, the book defies the false binary between rationality and imagination. This narrative choice deepens our empathy and expands our epistemology—how we know and why it matters.

Rundell’s essays suggest that awe is not weakened by understanding; if anything, knowledge intensifies reverence.

The Emotional Burden of Witnessing

Running beneath the ecological insight and poetic flourishes of Vanishing Treasures is a quiet but persistent emotional current: the grief of bearing witness to loss. The tone of the essays oscillates between celebration and elegy, admiration and mourning.

Whether describing a colony of seal pups drowned by melting ice or the eerie foresight of companies profiting from tuna extinction, Rundell writes with the consciousness of someone watching irreplaceable things disappear. This emotional burden is not numbing but galvanizing.

It transforms passive observation into active moral engagement. The book does not wallow in despair, but neither does it offer false hope.

Instead, it acknowledges the psychological weight of caring deeply in a time of collapse. The golden mole, shimmering in subterranean darkness, encapsulates this final tension—the beauty that survives unnoticed, perhaps doomed, yet still deserving of love.

Rundell insists that sadness is not weakness but an ethical response, and that love for animals must persist even when solutions seem distant. In this way, the act of witnessing becomes a form of stewardship.

The essays ask not only what animals are, but what kind of humans we want to be in relation to them. The burden of knowing is heavy, but necessary.

And it is through this weight that responsibility, and possibly redemption, emerges.