We Three Queens Summary, Characters and Themes

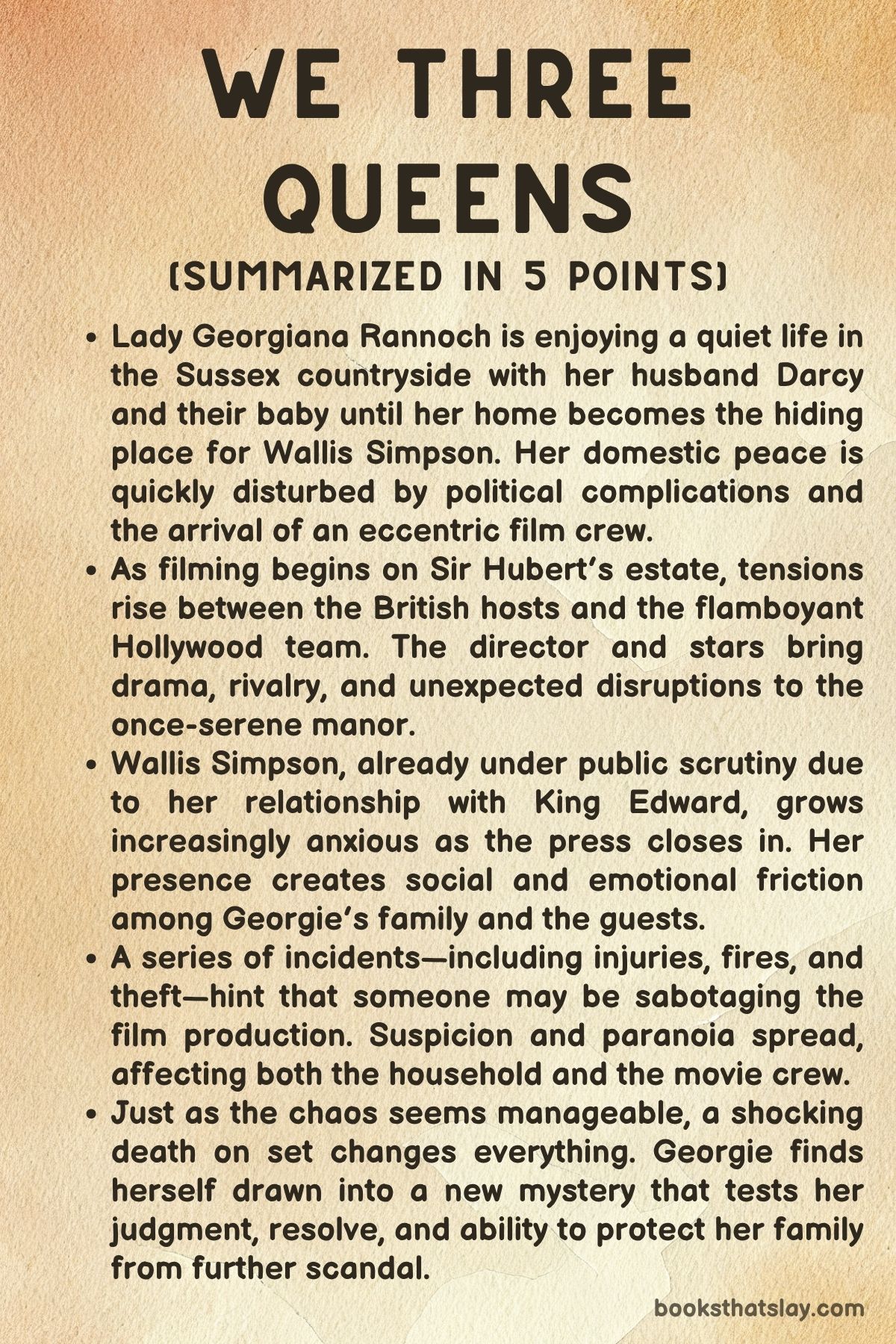

We Three Queens by Rhys Bowen is a historical mystery novel set against the backdrop of 1936 England, where political instability, royal scandal, and personal intrigue collide at a quiet country estate. At the center is Lady Georgiana, a charming, intelligent, and often overwhelmed aristocrat navigating the chaos that descends upon her life.

Her role as hostess to high-profile guests—including Wallis Simpson, the woman at the heart of King Edward VIII’s abdication crisis—thrusts her into a whirlwind of emotional turmoil, international drama, and a double dose of crime and celebrity. With humor, wit, and insight, Bowen crafts a story that is both socially observant and cleverly plotted.

Summary

Lady Georgiana begins the story basking in the rare comfort of peace. Married to Darcy and raising their son James at Eynsleigh Manor, her life finally seems stable.

However, her domestic bliss is short-lived. Her husband, freshly returned from a government mission to Germany, reveals troubling developments—Adolf Hitler’s regime is tightening its grip on Europe, and Georgiana’s mother is involved in a Nazi propaganda film and might soon marry a German man.

This would endanger her British citizenship and align her with a regime that Georgiana and Darcy distrust. On top of that, King Edward VIII—Georgiana’s cousin—is determined to marry Wallis Simpson, an American divorcée, threatening a constitutional crisis.

He requests that Georgiana hide Wallis at Eynsleigh to escape the press. Though reluctant, she agrees at Darcy’s urging.

Soon, the tranquil country home is anything but. Georgiana’s judgmental sister-in-law, Fig, arrives with her children, further disrupting the household.

Fig is critical of Georgiana’s modern parenting, and the tension between traditional expectations and Georgiana’s more relaxed values is ever-present. When Wallis Simpson arrives, she is dramatic, entitled, and dismissive of Georgiana’s home.

Complaining constantly, she nevertheless hides upstairs, fearing the press. The household begins to buckle under the strain of divided loyalties, social roles, and the politics of the day.

Compounding this chaos is the unexpected return of Sir Hubert, the estate’s owner, from America—with a full Hollywood film crew in tow. The crew is set to film a fictionalized and wildly inaccurate version of the lives of Henry VIII’s wives.

Georgiana must now manage a chaotic film set on top of her already difficult guests. The actors and producers—larger than life, demanding, and clueless about English customs—add to the confusion.

Among them are Grant Hathaway, who plays Henry VIII and makes inappropriate advances toward Georgiana, and Rosie Trapp, a pampered child star whose pushy mother demands constant attention.

Rosie bonds with Addy, Fig’s daughter, and Addy even becomes her stand-in. Meanwhile, Dorothy Hart, another young actress, forms a quiet friendship with Georgiana and confides about her discomfort with Hathaway’s behavior.

As filming progresses, Eynsleigh transforms into a surreal hub of royal scandal, family tension, and Hollywood glitz. Mrs.

Simpson grows more anxious, and Georgiana tries to offer moral support while maintaining decorum. Local boys Jacob and Donnie join the project as extras, deepening the mingling of local and celebrity worlds.

Then, the already strained atmosphere breaks when Rosie and Mrs. Simpson vanish.

Georgiana, alarmed, checks on her baby and niece before alerting the authorities. Chief Inspector Harlow arrives and begins an investigation.

The confusion is worsened by class misunderstandings and conflicting accounts of the last time Rosie was seen. Soon, a ransom note is delivered, demanding money and threatening harm if police are involved.

Mrs. Trapp insists on handling it herself, while Darcy prepares to shadow the drop.

Georgiana begins to suspect someone inside the house or the crew is involved. Suspicion falls on Jacob, the farm boy who might have unwittingly aided the kidnappers.

A visit to his family farm raises more red flags, and Georgiana’s fear deepens. As tensions rise, the spectacle of the press, the absurdities of the film world, and the cold calculations of aristocratic politics converge.

The reappearance of Georgiana’s glamorous mother adds comic relief but also highlights Georgiana’s longing for a more emotionally connected parent.

Eventually, Rosie is found alive, bringing momentary relief. But the real shock comes when Gloria Bishop, one of the actresses, is found murdered.

Investigations uncover her secret: Gloria was actually Jacob’s mother. She had fled an abusive husband years ago, reinvented herself as a star, and returned to England hoping to reconnect with her son.

But her ex-husband, learning of her reappearance, followed her and attacked her when she refused to give him money. Jacob, threatened and traumatized, helped him dispose of the body.

The murder reveals deep generational trauma, family secrets, and the harsh costs of escaping the past.

Parallel to this deeply personal tragedy is the escalating national crisis. King Edward VIII remains determined to abdicate for Wallis Simpson.

Despite efforts by the royal family to change his mind, he refuses, triggering anxiety throughout England. Georgiana’s husband Darcy is involved in these behind-the-scenes efforts.

Georgiana herself speaks with Queen Mary, who is distressed by her son’s defiance and worried about Bertie’s suitability as king. This conversation underscores the themes of duty, modernity, and tradition.

With the murder mystery resolved, Jacob is treated with compassion. Georgiana, Darcy, and Sir Hubert recognize the psychological scars he bears and offer him a chance to rebuild his life.

He is not villainized but portrayed as a victim of circumstances beyond his control. This empathy reflects Georgiana’s own resolve to raise her son with love and presence, unlike the emotionally distant parenting she endured.

In the end, Edward’s abdication becomes public. The nation braces for change, and Georgiana finally experiences a sense of closure.

Eynsleigh, once a peaceful home turned stage for drama and scandal, returns to quiet domesticity. Yet everything has changed—politically, emotionally, and socially.

Georgiana has grown stronger, more assured, and more resolute in her values. The novel closes with a fragile but enduring peace, as the characters look toward uncertain futures with renewed strength.

Characters

Lady Georgiana

Lady Georgiana is the heart and conscience of We Three Queens, and her evolution from a previously impoverished aristocrat to a resilient woman juggling domestic life, royal duty, and investigative challenges is central to the narrative. She is portrayed as intelligent, grounded, and deeply humane, marked by a remarkable ability to adapt to the absurdities of her social standing.

Though married into comfort, she maintains a practical perspective, resisting the haughty norms of the aristocracy. Her warmth and accessibility contrast with the cold detachment of many of her peers.

She consistently balances the tension between modern values and inherited traditions, as seen in her parenting choices and the way she treats guests and staff. Her empathy is evident in her concern for Rosie Trapp, her defense of Dorothy Hart, and her compassion toward Jacob, who becomes a tragic symbol of lost innocence.

Even under intense pressure—managing a royal scandal, a kidnapping, and a murder—Georgiana upholds her duties with grace, never losing her moral compass. She acts as a bridge between old-world aristocracy and a more modern, ethical sensibility.

Darcy O’Mara

Darcy O’Mara, Georgiana’s husband, operates in the shadowy world of espionage and government affairs, which often distances him from the domestic chaos at Eynsleigh. Though physically absent at crucial times, his presence looms large through his strategic thinking and moral clarity.

Darcy embodies loyalty and a quiet patriotism, evident in his clandestine missions and deep involvement in England’s political affairs, particularly the looming crisis around King Edward’s abdication. He trusts Georgiana implicitly and often supports her judgments even when they challenge traditional norms.

His steady, composed demeanor contrasts with the flamboyance and instability of the film crew and royal guests, anchoring the narrative’s more chaotic elements. Though he doesn’t dominate the story’s emotional core, his partnership with Georgiana reflects a rare equality in marriage during that era.

Wallis Simpson

Wallis Simpson is a forceful and polarizing figure in the narrative, characterized by self-importance, emotional volatility, and aristocratic disdain. Her presence at Eynsleigh is a symbolic intrusion—an embodiment of national controversy and personal entitlement.

She is not presented as evil, but as someone consumed by her role in history and overwhelmed by the consequences of her relationship with King Edward. Wallis is often dismissive of Georgiana’s domestic arrangements and critical of her choices, embodying a certain aloofness born of insecurity and fear.

Her anxiety over being discovered and the potential fallout of her presence at Eynsleigh reveal a vulnerability beneath the bravado. Still, her inability to show gratitude or empathy places her at odds with Georgiana, highlighting the cultural and personal chasm between them.

Fig (Figgy)

Fig, Georgiana’s sister-in-law, serves as a foil to Georgiana’s progressive and compassionate nature. She is rigid, snobbish, and obsessed with social propriety, constantly scrutinizing Georgiana’s parenting and household decisions.

Fig represents the clinging grip of the upper-class conservatism that Georgiana resists. However, Fig is not one-dimensional.

Her motivations—like wanting the best for her children or pushing Addy to earn money as a stand-in—are rooted in practical concerns, even if selfishly executed. Her character underscores the subtle pressures of class expectations and maternal ambition, offering a contrast to Georgiana’s more instinctual, empathetic approach to motherhood and duty.

Jacob Parsons

Jacob is one of the most complex and tragic characters in We Three Queens. Initially portrayed as a shy and evasive farm boy, Jacob’s true significance unfolds dramatically in the latter half of the novel.

His connection to Gloria Bishop—revealed to be his estranged mother—and his coercion by his abusive father pull him into the heart of the novel’s darkest moments. Jacob’s trauma and emotional silence speak volumes about the cost of abandonment, poverty, and violence.

His reluctant role in moving Gloria’s body is portrayed not as complicity but as a desperate act of survival. Georgiana’s empathy toward Jacob, and the way he is ultimately treated with compassion rather than condemnation, marks one of the story’s most poignant arcs, exposing the human cost of secrets and unresolved pain.

Gloria Bishop

Gloria Bishop embodies both Hollywood glamour and deep-rooted sorrow. Initially appearing as a flirtatious and attention-seeking actress, Gloria’s character later becomes a conduit for the novel’s exploration of shame, identity, and motherhood.

Her decision to return to England under a false name to film near her son suggests a longing for redemption or reconciliation. Her past—marked by an abusive marriage and the relinquishment of her child—casts a shadow over her glittering present.

Gloria’s death is shocking not only for its brutality but for the wasted opportunity for healing. In death, her true identity reshapes the narrative, forcing characters to confront the hidden costs of fame, secrecy, and family estrangement.

Rosie Trapp

Rosie Trapp, the young film star, symbolizes both the exploitative nature of the entertainment industry and the innocence it often consumes. Her disappearance catalyzes a major arc of the story, triggering panic, introspection, and unity among disparate characters.

Rosie is precocious and lonely, more accustomed to adult company and performance than childhood play. Her bond with Addy reveals a yearning for normalcy, and her situation draws attention to the pressures placed on child actors.

Her recovery is not just a resolution of plot but a moral reaffirmation—underscoring the need to protect childhood and challenge systems that commodify it.

Dorothy Hart

Dorothy Hart stands out as a quietly courageous presence in the narrative. Playing the role of young Mary Tudor, she is serious, sincere, and emotionally mature.

Dorothy confides in Georgiana about Grant Hathaway’s inappropriate behavior, illustrating the abuse of power and the importance of speaking up. Unlike the more self-involved guests, Dorothy connects with Georgiana on a deeper level, driven by mutual respect and vulnerability.

Her character lends a grounded realism to the tale, reminding readers of the silent strength often overlooked in chaotic environments.

Sir Hubert

Sir Hubert, the absent owner of Eynsleigh who returns mid-novel, offers comic relief and light-hearted eccentricity. His indulgence of the film crew and flirtation with Gloria Bishop suggest a man drawn to spectacle but ultimately harmless in intent.

Hubert represents the old guard of English gentry—tolerant, whimsical, and increasingly irrelevant. Yet his loyalty to Georgiana and Darcy, as well as his support during the crises that unfold, show him to be a dependable ally, even if occasionally impractical.

Queenie

Queenie, Georgiana’s servant and sometimes cook, is portrayed with affection and comedic flair. Often inept in her duties, she nonetheless provides essential support to Georgiana, particularly during the chaos brought on by the film crew.

Her interactions with the temperamental chef Pierre and her accidental culinary contributions underscore her unpredictability. Queenie represents the chaos of domestic life, but also the loyalty and warmth that run beneath the surface of even the most chaotic households.

King Edward VIII (David)

Though largely offstage, King Edward VIII—David—casts a long shadow over the novel’s events. His determination to marry Wallis Simpson despite political opposition introduces the broader theme of love versus duty.

David’s choices are treated with a mix of empathy and frustration, particularly through the lens of his cousin Georgiana. His abdication becomes symbolic of a generational shift, one that challenges the institutions of monarchy and tradition.

Addy

Addy, Georgiana’s young niece, adds a layer of innocence and emotional richness to the story. Her role as Rosie’s stand-in and her bond with the Hollywood starlet showcase her adaptability and kindness.

Through Addy, readers witness the contrast between a child’s natural exuberance and the artificiality imposed by fame. Her interactions with Georgiana and Fig also deepen the story’s exploration of differing maternal philosophies and class expectations.

Themes

Domestic Identity Versus Public Responsibility

The central conflict for Lady Georgiana arises from her attempts to cultivate a stable, personal life while constantly being drawn into high-stakes matters that are public, political, and historically significant. At Eynsleigh Manor, she envisions a peaceful existence focused on motherhood, modest domesticity, and privacy.

Yet this personal sanctuary is routinely invaded—first by Wallis Simpson and then by a chaotic film crew, both of whom symbolize disruptive elements from the outer world of fame, politics, and royal obligations. Georgiana is repeatedly forced to prioritize her duties to crown, family, or guests over her own comfort and emotional needs.

Her role as a hostess becomes symbolic of a larger burden: she must mediate not only social tensions but also national and personal responsibilities. The strain between her desire for a quiet, fulfilled life and the impositions of royalty and history plays out in increasingly absurd circumstances.

This internal struggle sharpens with each new intrusion, revealing how Georgiana’s identity as a wife and mother is constantly challenged by the expectations others place upon her because of her status. The push and pull between who she wants to be privately and what she must represent publicly form a constant, quiet tension throughout the novel, reflecting a broader commentary on the ways women in positions of visibility are rarely granted the luxury of self-containment.

Class Tensions and Social Pretense

Class differences permeate nearly every interaction at Eynsleigh, often presented with both humor and sharp critique. Georgiana herself straddles an unusual position: she is royal-adjacent but not wealthy, aristocratic by birth but progressive by nature.

Her household becomes a meeting ground for various social groups—the old aristocracy represented by her relatives and in-laws, the flashy and demanding American film crew, and the working-class characters like Queenie and Jacob, whose lives are dictated by necessity more than ceremony. The condescending attitude of figures like Wallis Simpson and Fig highlights the rigidity and entitlement often embedded in upper-class behavior, while the quiet resilience and earnestness of characters like Queenie and the farm workers subtly underscore the dignity of labor and lived experience.

Even Chief Inspector Harlow’s initial assumption that Georgiana is a servant reflects entrenched societal attitudes about appearances and class roles. The absurdities that arise from the Hollywood invasion—actors expecting butlers, crew members lounging in formal guest spaces, or producers treating aristocratic traditions with impatience—amplify the disconnect between social realities and performative elitism.

The novel satirizes these class tensions while also acknowledging the emotional cost of maintaining facades, particularly for someone like Georgiana, who is expected to move seamlessly between all these worlds.

Female Autonomy and Constraint

The novel offers a layered exploration of how women navigate a society structured to limit their independence. Georgiana, though relatively privileged, must constantly negotiate her voice and choices in a male-dominated world—whether it is Darcy deciding unilaterally to host Mrs.

Simpson or film producers assuming her home can be repurposed at will. Her internal compass often clashes with the social decorum expected of her.

The theme is even more pronounced with characters like Gloria Bishop, whose attempts to reinvent herself in Hollywood after surviving an abusive marriage end tragically. Her choice to abandon her son and recreate herself as a star is ultimately punished, not only by society’s judgment but by literal violence at the hands of her past.

Wallis Simpson, too, presents a provocative figure: she suffers publicly for her pursuit of love, labeled as a threat to the monarchy for daring to place personal happiness above institutional tradition. Even Rosie Trapp, a child, is treated as a commodity by her mother and the studio system.

Meanwhile, Dorothy Hart’s discomfort with inappropriate behavior on set reveals how young women are often forced to endure harassment in silence. Across these varied stories, the theme highlights the limited avenues for female empowerment, even as these characters try, in different ways, to assert control over their lives.

Georgiana’s final resolution to parent her son differently—to be present and emotionally available—signals a hopeful resistance against generational patterns of neglect and emotional suppression.

Scandal, Secrecy, and the Performance of Respectability

The narrative constantly oscillates between what is seen and what must remain hidden. The presence of Wallis Simpson is itself a secret with geopolitical consequences, and her concealment at Eynsleigh speaks volumes about the performance required to maintain appearances.

The film crew’s presence, ostensibly about reenacting royal history, becomes a parody of truth, turning respected historical figures into caricatures for entertainment. This layered performance—the actual filming, the roles people play in front of each other, and the careful concealment of scandal—serves as a running motif.

Gloria Bishop’s identity as Jacob’s mother is another carefully kept secret, rooted in shame and trauma. Her decision to hide her past ultimately leads to her death, suggesting that secrecy—especially about one’s origins—can be dangerous.

Rosie’s kidnapping initially masquerades as a mystery but reveals how vulnerable children are to adult manipulations and ambitions. Meanwhile, Georgiana must continually perform the role of perfect hostess and composed aristocrat even as her world spins out of control.

The need to uphold respectability, to keep scandal at bay, governs not only individual choices but entire lives. This theme underscores the performative demands of upper-class life, where truth is often secondary to appearances, and where the emotional cost of such deception is steep.

The Burden and Fragility of Loyalty

Loyalty is treated not as a virtue in We Three Queens, but as a complex, often heavy obligation. Georgiana is expected to show loyalty to her family, her class, her husband’s judgment, and her royal cousins.

This expectation becomes particularly burdensome when it clashes with her moral instincts or practical concerns. Her loyalty to duty demands that she host Wallis Simpson, despite personal objections.

Her loyalty to Darcy means supporting his government work and decisions, even when it exposes her household to danger. Jacob’s loyalty to his abusive father tragically reflects the darker side of familial allegiance: his silence and complicity are born not from agreement but from fear and emotional entrapment.

Even the loyalty of servants like Queenie, who continues to serve despite her chaotic efforts, underscores the often invisible labor behind such devotion. On a national scale, King Edward’s decision to abdicate for Wallis is framed as a loyalty to love over duty, with seismic consequences.

Georgiana’s growing awareness of how these loyalties can conflict—and even harm—those involved forces her to reflect on the values she wants to instill in her own family. Loyalty, in this world, is never simple; it is a tightrope walked between love, responsibility, and personal sacrifice.

The fragility of these bonds becomes clear in moments of crisis, when characters are forced to choose which version of loyalty they can live with.