You Can’t Hurt Me Summary, Characters and Themes

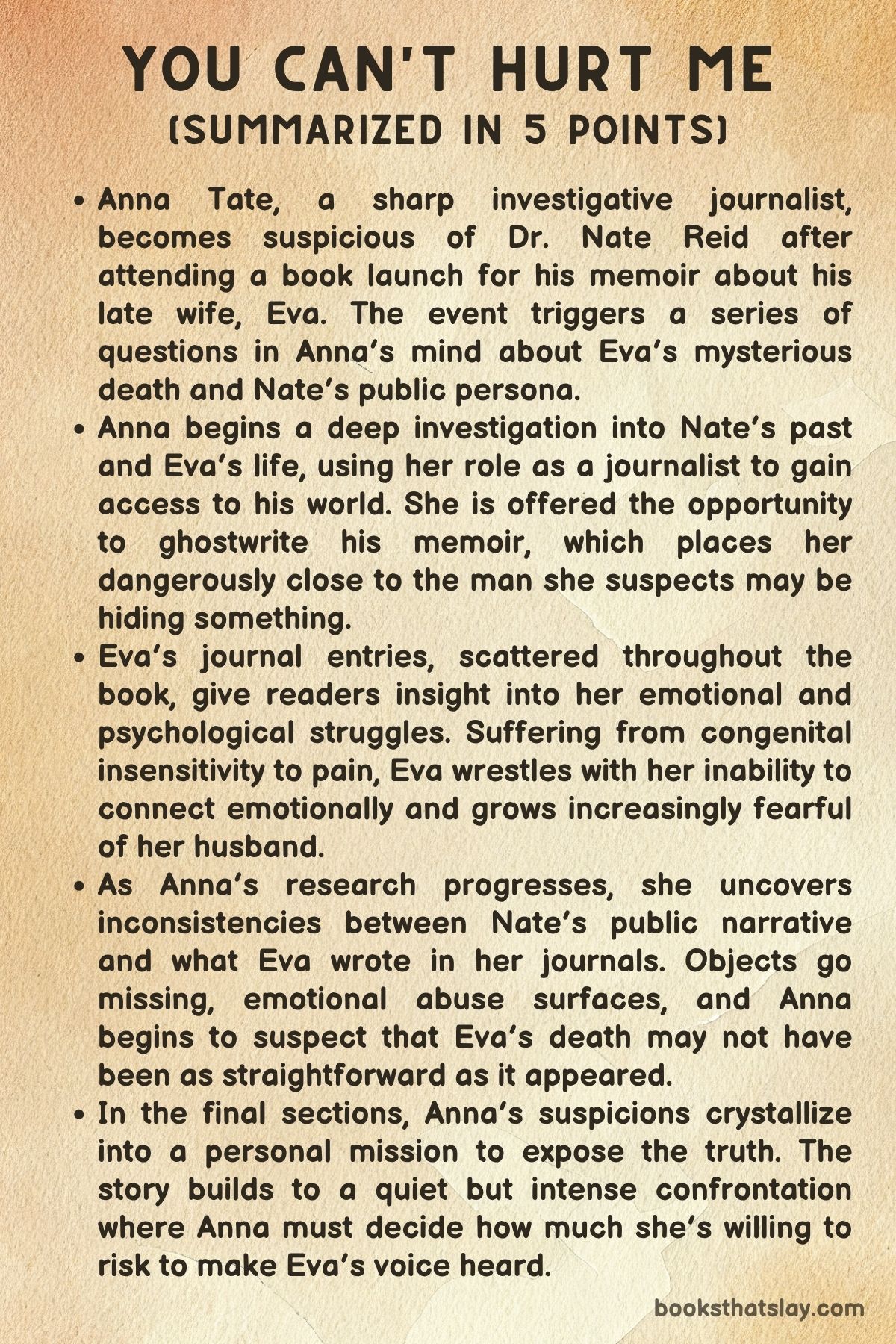

You Can’t Hurt Me by Emma Cook is a psychological thriller that navigates the treacherous boundaries between truth, memory, grief, and ambition.

At its core lies the story of Anna Tate, a journalist whose professional curiosity spirals into dangerous obsession when she becomes entangled in the lives of neuroscientist Dr. Nate Reid and his late wife Eva. What begins as an investigative profile morphs into a dark journey of ghostwriting, personal reckoning, and unraveling a mystery laced with trauma, betrayal, and buried secrets. With shifting loyalties and blurred moral lines, the novel examines the cost of storytelling and the damage inflicted by those who claim to speak for the dead.

Summary

Anna Tate attends a book launch under a false identity, blending into the crowd as she watches neuroscientist Dr. Nate Reid promote his memoir centered on his late wife, Eva.

To Anna, the ceremony reeks of fabrication and control, especially when a woman interrupts it, accusing Nate of murder. The interruption mirrors Anna’s own suspicions about the inconsistencies in Nate’s narrative.

Once comforted by literature, Anna now sees books as tools of manipulation, exemplified by Nate’s polished retelling of Eva’s life. Eva, a sculptor and therapist who lived with congenital analgesia, is being reshaped in public memory, and Anna suspects that the truth about her death is still obscured.

A year prior, Anna pitched a neuroscience article to her editor, a cover for her desire to become Nate’s ghostwriter. She had once spoken to Eva on the phone—an impactful conversation where Eva encouraged Anna to reclaim her own story rather than become a mere side character in others’.

Eva’s death soon after left Anna both haunted and intrigued. She sees ghostwriting Nate’s memoir as an opportunity to reclaim some power and perhaps uncover the real story behind Eva’s death.

Meeting Nate at the Rosen Institute, Anna is unexpectedly subjected to experimental pain trials—needles, burns, and emotional detachment. Her discomfort grows as she becomes the one being analyzed, reversing her usual journalistic role.

Yet she persists and gains access to Nate’s home, Algos House, the site of Eva’s supposed accidental death. The house feels curated and clinical, filled with order but devoid of warmth.

Eva’s niece, Jade, lives there too and acts defensively, unwilling to open up about what happened.

The circumstances of Eva’s death remain murky. Though officially labeled an accident, a first inquest hinted at suspicious bruising and the unexplained state of her studio.

Her sister Kath has pushed for a second investigation, believing that something was concealed. Meanwhile, fragments from Eva’s journal punctuate the narrative, offering an inside view into her struggles with authenticity, her resentment of Nate’s fascination with her condition, and her increasing disillusionment with their relationship.

Eva questioned whether her uniqueness made her lovable or simply useful—her identity becoming blurred under Nate’s gaze.

As Anna delves deeper, the tension with Nate increases. During a home interview, Anna secretly takes a photo of a personal image, provoking Nate’s cold anger.

His behavior vacillates between charm and calculated control, particularly when discussing Eva in emotionless, clinical terms. Yet he expresses interest in writing a memoir to humanize his grief, presenting Anna with an opportunity that is both professional and ethically fraught.

Anna’s personal life complicates her pursuit of truth. Her flatmate Amira is involved with Tony, Anna’s half-brother, whose relationship with Anna is shadowed by unresolved trauma from their shared past.

Abuse from their father and Tony’s manipulative tendencies continue to destabilize Anna. Her trauma deepens when she suspects that Tony is connected to Eva in ways he hasn’t admitted.

Despite professional risks, Anna continues her ghostwriting work. Her magazine botches a quote in her article, sensationalizing it, but Nate remains oddly nonreactive.

Instead, his publisher, Priya, offers Anna the ghostwriting job. Priya seems wary and perhaps romantically entangled with Nate.

As Anna and Nate collaborate, their relationship intensifies emotionally and physically, leading to ambiguous moments that further blur the professional boundary.

A trip to Dungeness reveals new truths. Nate opens up about Eva’s possessiveness and infidelity—specifically her affair with Priya—and confesses to Eva’s terminated pregnancy due to fears of passing on her condition.

These revelations make their marriage appear fractured and complex. The day ends in a kiss, pushing Anna into deeper emotional territory.

Soon after, Anna’s brother Tony confronts her, revealing he witnessed the kiss and reminding her of long-buried traumas, including their father’s death.

Back at Algos House, Anna finds Eva’s hidden journal and discovers a horrifying truth—Eva had been her therapist and had written about Anna’s personal disclosures. Anna was “Patient X.” The betrayal destabilizes her, but she continues the memoir, now knowing it is riddled with lies. Nate’s draft is devoid of real emotion, and Anna begins manipulating facts to craft a version of events that will resonate publicly.

Another kiss at a fundraiser and Priya’s announcement that Nate is moving to New York leave Anna feeling betrayed again—used for publicity and discarded when no longer needed.

In desperation, Anna contacts Kath, who reveals that Tony, not Nate, was the father of Eva’s unborn child. Nate had lied at the inquest about his whereabouts the night Eva died.

These revelations shift suspicion further. Anna discovers Tony’s name in Eva’s therapy notes and realizes that Eva had feared him.

He had confessed to being complicit in their stepfather’s death—information he used to control Anna. When Tony assaults Amira and begins stalking Anna, the danger becomes immediate.

The story hurtles to its climax when Tony confronts Anna and Nate at Algos House with a knife, accusing Nate of stealing Eva and driving her to suicide. During the ensuing struggle, Anna kills Tony in self-defense using one of Eva’s sculptures.

They stage the scene as a break-in, and Nate uses Eva’s journal to support their version of events. His memoir becomes a sensational bestseller, crafted from carefully selected truths.

Anna, however, finds her own voice. She writes her own book that challenges Nate’s narrative and reclaims Eva’s story.

Her book launch is a moment of resolution. Though she is still haunted by the trauma, Anna has chosen truth over complicity.

She sees someone she thinks is Nate in the crowd, but he disappears—a fitting metaphor for the ghosts she has finally begun to let go. Through pain and deception, Anna reclaims her story, refusing to be a footnote in anyone else’s book.

Characters

Anna Tate

Anna Tate stands at the emotional and narrative center of You Can’t Hurt Me. She is a journalist whose professional drive is fueled by a blend of ambition and unresolved trauma.

Anna enters the story seeking a scoop under the pretense of writing a feature on Dr. Nate Reid, but her motivations are deeply tangled with a desire to reclaim Eva Reid’s narrative.

Haunted by her past, especially the abusive legacy of her father and a toxic, incestuous dynamic with her half-brother Tony, Anna’s present actions are inextricably linked to her emotional wounds. Her relationship with books shifts from refuge to weapon, revealing a woman growing wary of language’s power to conceal rather than reveal truth.

Over time, Anna moves from passive observer to active participant, even manipulator, as her ghostwriting of Nate’s memoir becomes a quest not just for publication, but for control over narrative and meaning. Her arc is defined by increasing ethical compromise and disillusionment, culminating in a final act of violence that forces her to reckon with the moral ambiguities of survival, truth, and authorship.

By the novel’s end, Anna emerges bruised but empowered, finally reclaiming her agency through authorship of her own book and refusing to be anyone’s footnote again.

Dr. Nate Reid

Dr. Nate Reid is the enigmatic neuroscientist at the heart of You Can’t Hurt Me, whose polished grief and clinical demeanor mask a complex interior life.

A man obsessed with pain—both its absence and presence—Nate approaches life through the prism of control and dissection. His relationship with Eva, a woman incapable of feeling physical pain, doubles as both romantic partnership and scientific fascination.

He often appears cold, detached, even when discussing trauma or death, and this emotional remove becomes a shield against scrutiny. While publicly performing the role of grieving widower, he is privately manipulative, rewriting Eva’s legacy through a memoir curated for public consumption.

His interactions with Anna are laced with power dynamics: he tests her physically in pain experiments, emotionally through ambiguous affection, and professionally by making her a gatekeeper to his narrative. Nate’s revelations—his wife’s affair, the pregnancy, his knowledge of her secrets—reveal him as someone haunted by guilt but incapable of true vulnerability.

In the end, his complicity in moral transgressions is left ambiguous, yet he continues to thrive professionally, highlighting his capacity for self-preservation through narrative control and strategic charm.

Eva Reid

Eva Reid exists at the novel’s haunting core, more present in absence than she was in life. A therapist and sculptor with congenital insensitivity to pain, Eva’s existence is shaped by a condition that makes her both unique and unknowable—to others and to herself.

Through journal entries and memories, Eva’s psychological landscape emerges as conflicted and fractured. She questions her capacity for real empathy, resents being objectified by Nate for her uniqueness, and wrestles with the authenticity of her own creativity and relationships.

Her artistic work becomes a physical manifestation of inner torment—sculptures born of pain she cannot physically feel but emotionally senses. The revelation that she violated ethical boundaries by treating Anna and writing about her as “Patient X” adds a layer of tragic irony: the therapist who once seemed empathetic proves capable of exploitation.

Eva’s life becomes a contested narrative, shaped and reshaped by others after her death. Yet her own writings, discovered by Anna, offer a piercing counter-narrative—one that reveals a woman desperate to be seen for who she is, not what she represents.

Through Eva, the novel meditates on whether identity can ever truly belong to the person who lived it.

Tony

Tony is Anna’s half-brother, and perhaps the most volatile character in You Can’t Hurt Me. His presence is a living echo of Anna’s trauma, a catalyst for her psychological unraveling.

With a past marred by parental abuse and shared guilt over their stepfather’s death, Tony exists in a moral grey zone—charming yet dangerous, victimized yet manipulative. His rekindled romance with Anna’s friend Amira and his erratic behavior intensify the tension, as do revelations that he was both Eva’s patient and lover.

His violent tendencies surface when he assaults Amira and stalks Anna, behavior that mirrors the predatory control he’s exerted over her since childhood. Tony’s confession about his involvement in past deaths, coupled with his explosive jealousy and sense of betrayal, reveal a man ruled by resentment and emotional chaos.

His final act—confronting Anna and Nate with a knife—ends in his own death, a moment of catharsis for Anna but one that raises troubling questions about cycles of abuse and familial enmeshment. Tony represents the destructive potential of unprocessed trauma, and his demise symbolizes the painful but necessary severing of ties that have long defined Anna’s identity.

Priya

Priya is a shrewd and commanding presence in the world of publishing, acting as both gatekeeper and potential ally in Anna’s career. As Nate’s publisher, Priya walks a delicate line between professional loyalty and personal entanglement—there are hints of a past or ongoing romantic involvement with Nate, especially in the way she controls access and information.

She is skeptical of Anna, viewing her with a mixture of curiosity and disdain, and her interactions often place Anna on the defensive. Priya’s role is crucial in shaping the memoir’s trajectory, ensuring it aligns with market expectations while protecting Nate’s public image.

She represents the commercialization of grief, turning trauma into a consumable narrative. When she withholds key information—such as Nate’s move to New York—she exposes the fragile trust within their triangle, suggesting that professional alliances in this story are always laced with personal stakes.

Priya’s presence complicates the dynamics between Anna and Nate, and her final act of exclusion serves as a catalyst for Anna’s awakening to her own exploitation.

Kath

Kath, Eva’s sister, is a peripheral but vital character whose dogged pursuit of truth acts as a moral counterbalance to the rest of the cast. Unlike Nate or Anna, who manipulate the truth for personal or professional gain, Kath is driven by loyalty and justice.

She refuses to accept the sanitized version of Eva’s life and death, pushing for a second inquest and exposing inconsistencies that others would rather bury. When Anna finally turns to her, Kath offers a clear-eyed view of Nate’s manipulation and Eva’s unacknowledged suffering.

Her warnings shake Anna from complicity and reignite the ethical fire at the heart of her investigation. Though she operates mostly from the margins, Kath’s unwavering belief in her sister’s truth gives voice to the story’s central theme: that narratives shaped by grief and ambition can never replace the raw, inconvenient facts of a life.

Amira

Amira, Anna’s flatmate and briefly Tony’s lover, plays a key role in illuminating Anna’s fractured sense of loyalty and vulnerability. Initially presented as a stabilizing presence, Amira becomes a source of discomfort as she re-engages romantically with Tony.

Her involvement with him dredges up Anna’s suppressed traumas and triggers deep insecurity. Amira’s eventual assault at Tony’s hands catalyzes a crucial turning point—forcing Anna to confront the danger he poses not only to others but to herself.

Amira’s character represents the normalcy and ethical compass that Anna risks losing in her obsessive quest for truth. Though not heavily featured, her fate acts as a moral wake-up call for Anna, reminding her of the real-world stakes of the psychological web she’s entangled in.

Jade

Jade, Eva’s niece and current resident of Algos House, is a quiet yet unnerving presence who adds further ambiguity to the narrative. Her loyalty to Nate is unsettling, especially given the unclear circumstances of Eva’s death.

Jade’s caginess and defensiveness hint at knowledge she’s unwilling—or afraid—to share. As a character, she embodies the unsettling power of secrets passed between generations and households.

Her silence is not empty but laden with complicity, grief, and possible fear. Though her role remains minor, she serves as a spectral presence, much like Eva, underscoring the layers of control, suppression, and performance that define Algos House.

Her existence within Nate’s domain is a subtle yet significant marker of the novel’s overarching question: who gets to tell the story, and who is silenced by the telling.

Themes

Narrative Ownership and the Ethics of Storytelling

The question of who gets to tell a story—and how it is shaped by power, proximity, and motive—lies at the heart of You Can’t Hurt Me. Through Anna’s pursuit of ghostwriting Nate Reid’s memoir, the novel examines how narratives are not static reflections of truth but dynamic tools used to assert control, exonerate guilt, or shape public perception.

Anna’s initial intent to write about Nate under the pretext of a science feature gradually becomes a deeper, more ambiguous desire to reclaim Eva’s legacy. What starts as professional curiosity evolves into a moral obligation, especially as she uncovers distortions in Nate’s version of events and grapples with the weight of Eva’s journal.

The layers of storytelling—Nate’s memoir, Eva’s private writings, Anna’s article and eventual book—form a contested battlefield over legacy and truth. The ethical dilemmas of ghostwriting become clear when Anna, ostensibly giving voice to someone else, begins to manipulate facts for impact.

Her own trauma, loyalties, and ambition blur the lines between justice and self-preservation. This theme reveals how stories can simultaneously illuminate and obscure, heal and harm.

It challenges the reader to consider the cost of authorship, especially when the subject is no longer alive to offer consent or correction. In reclaiming Eva’s story, Anna must confront not only what has been hidden but also the uncomfortable reality that truth, when filtered through memory and motive, may never be fully recoverable.

Pain, Vulnerability, and Control

Throughout the novel, pain—physical, emotional, and psychological—functions as both a literal and metaphorical force. Eva’s congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP) is not portrayed as a superhuman advantage but as an existential curse.

Her inability to feel becomes symbolic of deeper emotional disconnection, as she struggles with authenticity, empathy, and intimacy. Nate’s obsession with studying pain, including his experimentation on Anna, is disturbingly clinical, revealing his need to dominate and dissect what he cannot emotionally process.

Anna’s willingness to endure these trials speaks volumes about her fractured relationship with control and her history of trauma. Pain is framed as something that defines personhood and connects individuals to the world—when it is denied, minimized, or pathologized, one’s sense of identity can disintegrate.

The novel also examines how trauma lingers, shaping behavior and emotional response. Anna’s relationship with Tony, marked by blurred boundaries and unresolved childhood suffering, underscores the theme’s psychological depth.

The act of ghostwriting itself becomes a form of emotional exposure: by trying to write about others, Anna inadvertently writes herself into the text, confronting her own vulnerability. Pain is not just something inflicted—it is something survived, hidden, and, at times, performed.

In the end, control over pain—whether physical like Eva’s or emotional like Anna’s—becomes a contested terrain where power is exerted and identities are negotiated.

Power, Manipulation, and Gender

The novel is deeply invested in exposing the subtle and overt manipulations that operate in personal relationships, particularly along gendered lines. Nate, a charismatic and calculating neuroscientist, embodies a form of male dominance that cloaks itself in civility and intellect.

His charm, professionalism, and grief are revealed to be curated performances, masking a need to dominate women emotionally, intellectually, and even biologically. His control over Eva—presented as both muse and subject—reflects how women’s pain is often aestheticized or co-opted for male advancement.

Anna, despite her initial skepticism, is not immune to Nate’s influence. Her growing entanglement with him—personal, professional, and romantic—highlights how even critical observers can be ensnared by charisma and power.

Similarly, Tony, her half-brother, wields emotional manipulation and threat in a more chaotic but equally coercive way. The legacy of childhood abuse and incestuous undertones reveal the long-term psychological scars of male control over female agency.

The women in the novel—Eva, Anna, Amira, Kath—are often left to navigate the emotional wreckage of male violence and secrecy. Even Priya, Nate’s publisher, appears complicit in maintaining the façade, benefiting professionally from the sanitized narrative.

This theme offers a nuanced critique of how women’s voices and experiences are often marginalized or reinterpreted to serve the ambitions of powerful men, and how reclaiming that agency can be both liberating and dangerous.

Memory, Guilt, and Self-Destruction

Memory in You Can’t Hurt Me is not a static archive but a volatile, emotionally charged space. Anna’s recollections are fragmented, tainted by trauma and repression.

Her past with Tony and their shared guilt over their father’s death haunts her present, influencing her decisions and relationships. The guilt she carries is compounded by her eventual realization that Eva once treated her as a patient, ethically violating her trust.

This moment forces Anna to reevaluate her memories of Eva, understanding that even her idealized impressions were colored by deception. Nate, for his part, also exhibits selective memory—omitting or justifying aspects of his relationship with Eva to maintain a coherent self-image.

His story of Eva is meticulously edited, reframing her abortion, her affair, and her emotional distance as components of a tragic love story rather than symptoms of mutual dysfunction. Guilt is shown to be a corrosive force, one that can manifest in self-sabotage, denial, and moral compromise.

Anna’s descent into complicity—altering facts, covering up Tony’s death, maintaining her silence—demonstrates how guilt, when not addressed, can turn victims into collaborators. The novel interrogates the reliability of memory and the ethics of redemption.

It suggests that confronting the past with honesty is painful but necessary, while avoiding it only perpetuates cycles of harm.

Grief as Performance and Commodity

One of the novel’s most disturbing insights is its portrayal of grief not as a private emotional process but as something that can be curated, performed, and even monetized. Nate’s public grief is suspect from the start—his polished speeches, his meticulous control over Eva’s image, and his willingness to profit from her story raise uncomfortable questions.

The line between mourning and self-marketing blurs as his memoir becomes a bestseller, sanitized and seductive in equal measure. Anna, too, becomes complicit, shaping a narrative that she knows is emotionally resonant if not entirely truthful.

The publishing industry’s role in commodifying pain is sharply critiqued through characters like Priya, who is more concerned with marketability than authenticity. Eva’s posthumous portrayal is filtered through competing agendas: scientific marvel, tragic muse, artistic genius.

Yet her private journals suggest someone deeply conflicted, longing to be understood for who she was—not for what made her unusual or profitable. This tension between authentic mourning and performative grief also plays out in Anna’s internal world.

Her efforts to mourn Eva, make sense of Tony, and process her family history are complicated by her public responsibilities as a writer. The theme underscores how capitalist and patriarchal systems often co-opt personal suffering, turning human experience into content.

It ultimately poses the question: can grief ever be honest when its expression is mediated by ambition, fear, or economic incentive?

The answer remains unsettlingly ambiguous.