Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert Summary, Characters and Themes

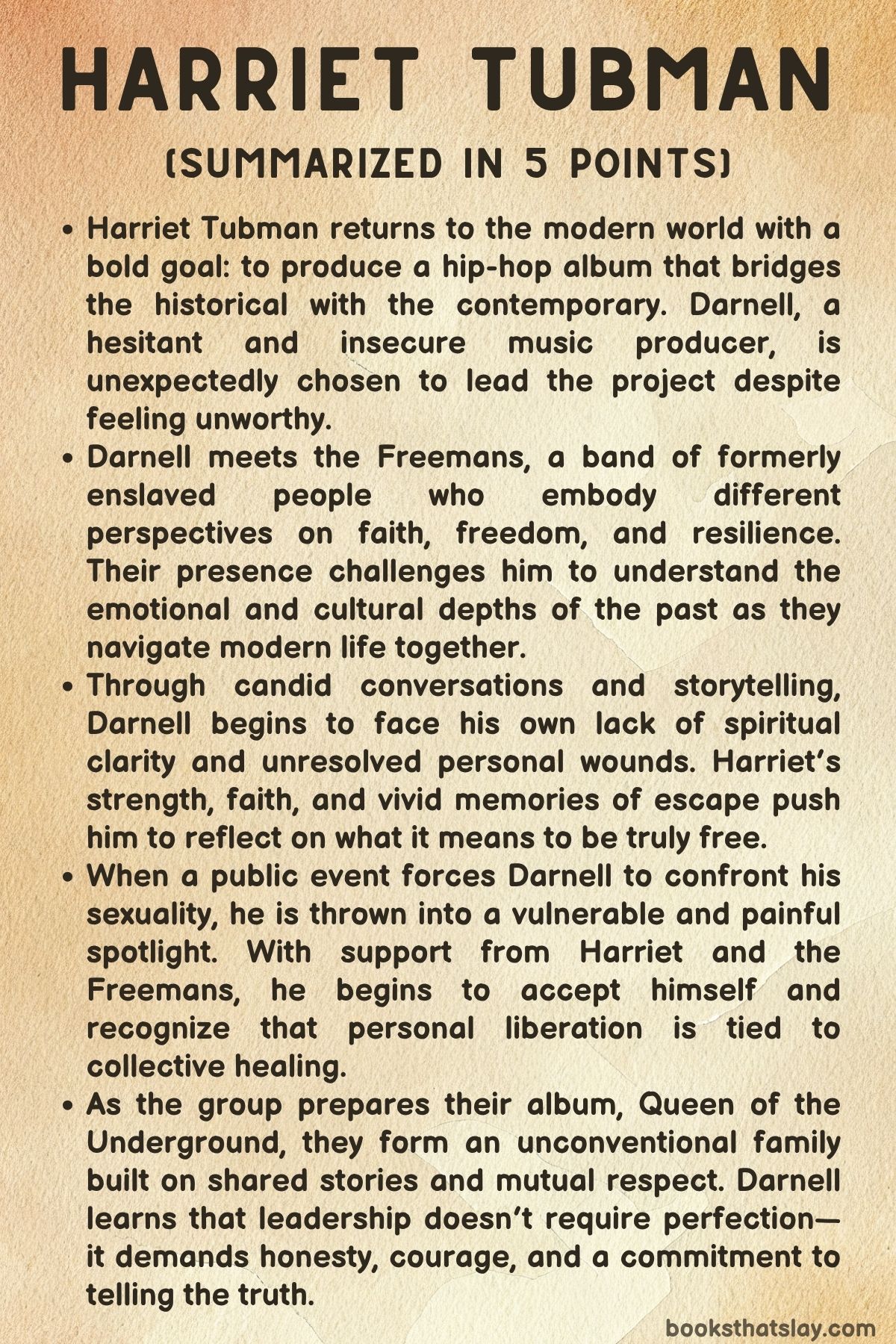

Harriet Tubman: Live in Concert by Bob the Drag Queen is a boldly inventive novel that reimagines one of America’s most iconic historical figures in an unexpected and satirical light. Told through the eyes of a disillusioned music producer named Darnell, the story follows the miraculous return of Harriet Tubman to the modern day with a singular mission: to produce a hip-hop album that fuses the spirituals of her era with contemporary Black musical expression.

Infused with humor, Afrofuturism, and deeply personal reckoning, this novel is not just a tale of cultural remixing—it’s a confrontation with trauma, legacy, queerness, and the evolving meanings of liberation. With vivid characters, sharply tuned dialogue, and moments of radical reflection, the novel questions what it means to be free in body, mind, and spirit.

Summary

Darnell, a once-successful music producer turned industry has-been, is unexpectedly summoned by none other than Harriet Tubman—alive and imposing, with a powerful aura of conviction. Tubman informs him that she plans to make an album that merges Negro spirituals with modern hip-hop, creating a sonic bridge across generations of Black resistance and expression.

Though Darnell is skeptical and insecure about his relevance, he’s drawn into her confidence and embarks on the surreal project.

Darnell is introduced to Tubman’s musical ensemble, the Freemans, each of whom was once led to freedom by Harriet herself. Among them are Odessa, a gracious former house slave navigating a bewildering modern world; Buck, a fiercely intelligent guitarist critical of Christianity; Quakes, a peaceful Quaker DJ with dwarfism; and Moses, Harriet’s deeply empathetic brother.

These characters offer layered insights into the legacy of slavery and its emotional and spiritual aftermath. Darnell bonds especially with Odessa during a walk through Harlem, where the sensory overload of the present day unsettles her.

Her confusion underscores the emotional rupture between past and present.

As Darnell listens to the Freemans’ stories, he gains an education in the personal dimensions of historical trauma. Odessa’s account of her life in proximity to white power, and her liberation during the Combahee River Raid, challenges Darnell to consider what he has done with his own freedom.

Conversations with Quakes lead to a gentle but illuminating examination of faith, while Buck provides a far more confrontational critique of religion, reminding Darnell that spiritual institutions often colluded in Black subjugation.

The project deepens in meaning when Harriet shares the story of her first escape, highlighting the tactical use of spirituals like “Wade in the Water” to convey secret messages. Her tales of physical injury, divine visions, and unwavering purpose overwhelm Darnell.

He breaks down in her arms, cracked open by awe, humility, and the slow reclamation of purpose. From this moment on, the boundaries between music production and spiritual restoration begin to blur.

The group experiences a new level of intimacy after Harriet collapses during one of her trances. These incidents, initially mistaken as medical emergencies, are revealed to be spiritual communions that leave her physically spent.

With Harriet incapacitated, Darnell must step up. He begins organizing the music sessions, leaning into a leadership role he never imagined for himself.

Moses, ever humble and grounded, becomes Darnell’s quiet mentor, offering reassurance and reminding him that greatness comes in many forms.

A particularly moving scene unfolds when Moses shares how Harriet would signal her presence in the woods by singing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot. ” This revelation leads to a powerful communal moment in the studio, where the group sings together, transforming the space into a living altar of memory and sound.

Darnell, now more than just a producer, is becoming the custodian of stories that demand to be remembered.

As the sessions continue, Darnell gains new understanding of the high-stakes dangers Harriet faced while running the Underground Railroad. Buck describes the harsh truth of betrayal—sometimes even by other Black people—under the pressure of survival.

Harriet’s threat to shoot deserters is recontextualized not as ruthlessness, but as a tragic necessity for the safety of all involved. These revelations shatter any sanitized version of history Darnell might have held.

When Harriet recovers, she confronts Darnell directly. She accuses him of not being free, challenging him to name what still holds him back.

It’s a raw moment, one that reframes freedom as a multidimensional journey rather than a single moment of release. Harriet promises to help Darnell reach his promised land, reframing her role from historical hero to personal guide.

Soon after, Darnell is scheduled for a live television appearance with Slim, a famous rapper and his old acquaintance. The event is meant to be a mutual coming-out moment.

However, during the interview, Slim outs Darnell on air without his consent. Darnell is humiliated and furious, confronting Slim off-stage and walking out.

In the aftermath, he returns to Harriet and the Freemans, who accept him without hesitation.

Harriet reminds him that freedom is not just individual—it echoes through generations. Moses tells him the story of William Dorsey Swann, a real historical figure who was a formerly enslaved man and the first self-proclaimed drag queen.

These stories reclaim queerness from historical erasure, helping Darnell understand that his identity has always had a place in the broader fight for liberation.

With renewed focus, Darnell throws himself into producing the album, now titled Queen of the Underground. The creative process becomes a collaborative act of healing.

Harriet’s presence binds the group together, but it’s Darnell’s voice and leadership that propel them forward. When Slim returns, now a record label executive and aligned with old friends, Darnell refuses to be manipulated again.

He knows who he is, and what he stands for.

Harriet continues to guide Darnell with stories of courage, including the story of Ellen Craft, a woman who escaped slavery by disguising herself as a white man. When Darnell compares his workload to slavery, Harriet corrects him forcefully.

The moment becomes a hard but essential reminder of the gravity of real suffering. Moses gently supports Darnell afterward, helping him see the path forward lies in acknowledging missteps and learning from them.

The album is completed, and the group prepares for a concert at the Apollo. Quakes adds dramatic flair to the stage design, transforming the show into a historical and cultural event.

On the night of the performance, Darnell is a mix of nerves and anticipation. Harriet tells him her work is done—it’s now his time to lead.

As the curtain rises, Darnell walks on stage fully himself: a Black, queer, formerly lost man now grounded in legacy, music, and purpose. In stepping forward, he steps into freedom—not just for himself, but for everyone listening.

Characters

Darnell

Darnell, the narrator of Harriet Tubman, is a complex character whose emotional arc anchors the entire narrative. Initially portrayed as insecure and washed-up, Darnell is burdened by feelings of inadequacy after his failed career as a music producer.

His self-doubt is amplified when he’s summoned by none other than Harriet Tubman, a towering historical figure he reveres. This reverence borders on paralyzing, leaving him fumbling in her presence and questioning why he was chosen.

Yet, Tubman’s unwavering faith in his potential forces Darnell to confront parts of himself he’s long buried. Over the course of the story, Darnell’s emotional transformation is profound.

He evolves from someone alienated from faith, history, and self-worth into a figure of purpose and conviction. His public outing, forced upon him by Slim, triggers both a breakdown and a breakthrough, compelling him to shed shame and own his identity as a queer Black man.

The support of the Freemans and Tubman helps him reclaim agency, not just in his career, but in how he chooses to live and lead. Ultimately, Darnell becomes the successor to Tubman’s mission—not in a literal historical sense, but in the spiritual sense of shepherding others toward liberation, creativity, and authenticity.

Harriet Tubman

In Harriet Tubman, Harriet Tubman is not merely resurrected for narrative shock—she is reimagined as a timeless, prophetic force with a fierce vision. Still carrying the battle scars of her past, Harriet commands attention with her moral authority, divine connection, and unyielding resolve.

She is equal parts warrior, artist, and spiritual guide. Her decision to record a hip-hop album isn’t played for absurdity; it becomes a bold act of cultural fusion, meant to link the coded messages of spirituals with the rhythmic urgency of contemporary Black life.

Tubman’s spirituality is profound, manifesting in physically draining divine episodes that reinforce her connection to a higher purpose. Her collapses aren’t moments of weakness, but proof of her sacrificial leadership.

Even her sternness carries deep love—when she chastises Darnell for likening his work to slavery, it’s not to humiliate him but to restore the sacred gravity of her legacy. Her challenge to Darnell—“you ain’t free from something”—is both a provocation and a promise.

In Tubman, we see a character who transcends time to become a living metaphor for intergenerational freedom and unflinching truth.

Odessa

Odessa is a former house slave whose gentleness and genteel mannerisms mask a deep well of pain, insight, and resilience. She embodies the complexities of proximity to whiteness during slavery—treated with superficial kindness, yet subject to the same dehumanization.

Her reflections on her experience, especially during the Combahee River Raid, reveal a nuanced understanding of survival, liberation, and the costs of being “freed. ” When she walks through Harlem, her wonder and disorientation expose the deep emotional rift between past and present.

Odessa is not naïve; she is fully aware of the emotional toll of having lived so long under someone else’s control. Her bond with Darnell is one of mutual respect, offering him both nurturing support and pointed questions about what he does with the freedom she never took for granted.

Odessa represents not only historical pain but the grace and clarity that can come with surviving it.

Buck

Buck is a thunderstorm of righteous rage, intellect, and defiance. As a guitarist and a proud atheist, Buck forcefully rejects Christianity, which he sees as a tool of Black oppression used to pacify enslaved people.

His fury is not reckless but deeply rooted in a painful, clear-eyed reading of history. He offers a powerful counterpoint to Quakes’ gentle spirituality and Tubman’s divine visions, providing a necessary reminder that liberation can also be secular, intellectual, and born of indignation.

Buck’s stories about betrayal—especially Black bounty hunters used to sabotage escapes—reveal a layered understanding of how systems of oppression manipulate even the oppressed. Yet beneath his anger lies loyalty and conviction.

He may not embrace God, but he believes in the power of community and in Harriet’s mission. Buck pushes Darnell to confront uncomfortable truths and reframe what it means to be “free.

” He is the embodiment of resistance forged in the fire of history.

Quakes

Quakes, a dwarf Quaker DJ, is the group’s spiritual anchor and quiet philosopher. His peaceful demeanor and gentle wisdom contrast with Buck’s volcanic intensity, and this difference creates space for dialogue around faith, forgiveness, and healing.

Quakes doesn’t impose belief but embodies it, allowing Darnell to encounter faith as something soothing and expansive rather than dogmatic or coercive. His spirituality feels organic, rooted in humility and love, making him a safe presence for both Odessa and Darnell.

Despite his small stature, Quakes occupies a large emotional space in the story, guiding others through his music and his insight. His creative flair, particularly in helping design the show’s spectacle, showcases his theatrical imagination and reverence for history.

Through Quakes, the narrative reminds us that spirituality need not be loud to be powerful—and that gentleness can be revolutionary.

Moses

Moses, Harriet’s younger brother, is the emotional backbone of the Freemans and the most grounded of the group. While Harriet is a mythic figure and Buck an ideological firebrand, Moses is deeply human, accessible, and empathetic.

His stories bring intimacy to the historical weight of the narrative—like how Harriet signaled her presence with songs in the woods. Moses represents the importance of familial bonds and the sustaining power of memory.

His calm presence provides Darnell with a model of masculine tenderness and grounded strength. When Harriet collapses, Moses doesn’t panic; he supports Darnell and subtly urges him to step into leadership.

Later, his recounting of queer historical figures like William Dorsey Swann challenges erasure and offers Darnell a lineage of queer resilience. Moses shows that heroism isn’t always grand—it can live in everyday care, steady support, and honest storytelling.

Dr. Slim

Dr. Slim serves as both foil and catalyst in Darnell’s journey.

A successful rapper hiding his sexuality, Slim embodies the contradictions and pressures of hypermasculinity in the hip-hop world. His decision to out Darnell on live television is a profound betrayal, one that forces Darnell into a painful reckoning with his own silence.

Slim’s actions are shaped by fear and a desire for control—his own coming-out is tied to publicity and image management. Despite this, Slim’s presence is necessary.

He reflects the compromises some make in navigating fame and queerness in a hostile industry. When he returns later in the narrative, now running a major label and aligned with Raphael, Slim appears more self-possessed but still untrustworthy.

Darnell’s refusal to be manipulated by him a second time signals growth and resolve. Slim’s role is not redemptive, but instructive—he helps illuminate the cost of denial and the courage of truth.

Suzanne

Suzanne, Darnell’s manager, is a figure of ambition and performance management. Focused on optics and control, she pressures Darnell into the public eye, insisting Slim is the “main event.

” She represents the impersonal mechanisms of the entertainment industry—concerned with branding over well-being. While not malevolent, Suzanne’s tunnel vision makes her blind to the emotional stakes of Darnell’s outing.

Her character adds tension and realism to the story, reminding readers that even well-intentioned allies can cause harm when they prioritize success over humanity.

Big House and Raphael

Big House, a closeted mentor from Darnell’s past, symbolizes the hidden lineage of queerness in hip-hop—a lineage often erased or buried. Charismatic and tragic, Big House taught Darnell how to survive in a homophobic industry.

His memory haunts the narrative as a cautionary tale about the dangers of never living truthfully. Raphael, his former partner, appears later as Slim’s husband, further complicating the personal and professional web Darnell must navigate.

Together, Big House and Raphael’s story gestures to the unseen queer histories that exist within all spaces, even those that pretend to be monolithic. They serve as reminders that identity is never isolated, but part of a larger, often silenced legacy.

Themes

Historical Memory and the Reanimation of Legacy

Harriet Tubman reshapes the concept of legacy by bringing a revered historical figure into the present day, not as a distant icon but as an active agent of cultural relevance. Harriet’s decision to create a hip-hop album is more than a fantastical conceit—it’s a statement about the continuous need to transmit memory across generations in forms that resonate.

The Negro spirituals she once relied on were revolutionary in their time, functioning as both coded language and spiritual sustenance. By fusing these with hip-hop, a genre birthed from urban Black expression and political struggle, Harriet seeks to ensure that the language of resistance does not stagnate.

The past is not a museum exhibit in this narrative; it’s a living, rhythmic force that insists on modern reinterpretation. Harriet’s ability to converse and collaborate with a present-day producer like Darnell blurs the boundary between historical myth and lived memory, showing that the fight for freedom did not conclude with emancipation—it merely changed battlegrounds.

Her presence interrogates how we sanctify historical figures into inaction, stripping them of their urgency. Instead, this book animates Tubman as a vessel of wisdom and fire, demanding that the legacy of survival, rebellion, and vision be actively engaged with, not simply admired.

Personal Liberation and Queer Identity

Darnell’s coming out journey occupies a central arc in the novel’s emotional structure, offering a deeply personal counterpoint to Harriet Tubman’s broader political mission. His sexual identity, long suppressed by fear of judgment, industry homophobia, and internalized shame, parallels a different kind of bondage—one that restricts truth rather than physical movement.

The public outing orchestrated by Dr. Slim is a violent rupture, exposing how queer identities are still manipulated, exploited, and erased, especially in spaces like hip-hop that have traditionally upheld heteronormative masculinity.

But this rupture also becomes a moment of transformation. With Harriet and the Freemans by his side, Darnell is reminded that the path to freedom, though painful, is essential.

Harriet reframes liberation as a spiritual and psychological act, not limited to historical slavery. Her confrontation—”you ain’t free from something”—pierces through Darnell’s defenses, urging him to interrogate his own silences.

Through Moses’ recounting of William Dorsey Swann and other forgotten queer figures, the book restores queer visibility into Black history. This theme reveals that self-acceptance is not an isolated goal but a political act, one that reclaims space and history that has been denied.

Darnell’s eventual pride in his identity, and his refusal to be commodified by Slim’s publicity stunts, marks a radical shift from fear to agency, mirroring Harriet’s own fearless approach to resistance.

Faith, Spirituality, and Sacred Purpose

The story presents multiple views on faith, not as a uniform system, but as a constellation of beliefs and doubts that define the characters’ inner lives. Harriet’s spiritual calling is central—her visions, her collapses into communion, and her unwavering sense of divine mission offer a portrayal of faith that is not rhetorical but visceral.

She sees her purpose as anointed, and this certainty gives her not just courage but clarity. Contrasting her are Buck and Darnell, whose relationships to religion are strained or hostile.

Buck sees Christianity as a tool of enslavement, wielded by oppressors to pacify the enslaved. His anger is rooted in historical betrayal, and his atheism is a form of resistance.

Darnell, initially caught between reverence and resentment, finds himself challenged by both perspectives. It’s through his interactions with Quakes and later Harriet that he begins to reconsider faith—not as blind obedience, but as a deep connection to history, music, and moral responsibility.

Spirituality in this book is not about worshipping a deity; it’s about belief in something bigger than the self. Whether that’s justice, liberation, or creative purpose, each character channels this energy differently.

Ultimately, Harriet’s example convinces Darnell that purpose without faith is hollow, and that leadership requires a belief in one’s power to affect others, even in the absence of complete certainty.

The Weight of Leadership and Legacy

Darnell’s arc is defined by his gradual acceptance of responsibility. Initially introduced as a down-on-his-luck producer full of self-doubt and imposter syndrome, he is reluctant to see himself as anything but secondary.

His role as a reluctant sidekick to Harriet contrasts sharply with the grandeur of her mission. But as Harriet begins to physically and spiritually wane, it becomes clear that she’s not here to reclaim her old mission—she’s here to pass it on.

Her collapse is symbolic, transferring weight to Darnell. The moment he instructs the Freemans to sing and carry on the project in her absence signals a shift: he begins to embody the leadership he once deferred.

The narrative frames leadership not as innate brilliance but as chosen accountability. Darnell becomes a steward of Harriet’s vision, not by mimicking her, but by interpreting it through his own lens.

His missteps—especially his flippant comparison between music production and slavery—highlight that leadership also involves correction, humility, and growth. Harriet’s stern response is not a dismissal, but a reminder of the stakes.

Moses, Odessa, and Quakes become mentors and mirrors, showing him how legacy must be earned through integrity, not assumed through proximity. By the story’s end, Darnell no longer hides behind others; he steps forward, not because he believes he’s ready, but because the work must go on—and he’s the one left to carry it.

Music as Resistance and Cultural Memory

Music in Harriet Tubman is not entertainment; it’s language, memory, and resistance. From the spirituals that signaled danger or freedom during Tubman’s rescues, to the beats and verses of hip-hop that narrate urban survival, the book presents music as a lineage of defiance.

Harriet’s desire to blend spirituals with hip-hop is not a gimmick—it’s a mission to restore context and meaning to sounds that have often been commodified or sanitized. Darnell’s role as a producer becomes an act of cultural archaeology, not just mixing sounds but reconstructing stories.

The album they create, Queen of the Underground, becomes a metaphorical railroad of its own, transporting listeners through pain, survival, and triumph. Every member of the Freemans contributes something to this process, reflecting the communal nature of both spirituals and rap.

Whether it’s Quakes with his DJ flair, Buck’s raw emotion on guitar, or Odessa’s poignant storytelling, their collaboration reclaims music from being a product and reestablishes it as power. Even the final performance at the Apollo is more than a concert—it’s a resurrection, a proclamation, and a reminder that music has always been the pulse of Black resistance.

Through rhythm, harmony, and lyric, the album doesn’t just entertain; it educates, consoles, and calls to action. It insists that the past is not silent—it sings, it shouts, and it demands to be heard anew.