Propaganda Girls Summary, Characters and Themes | Lisa Rogak

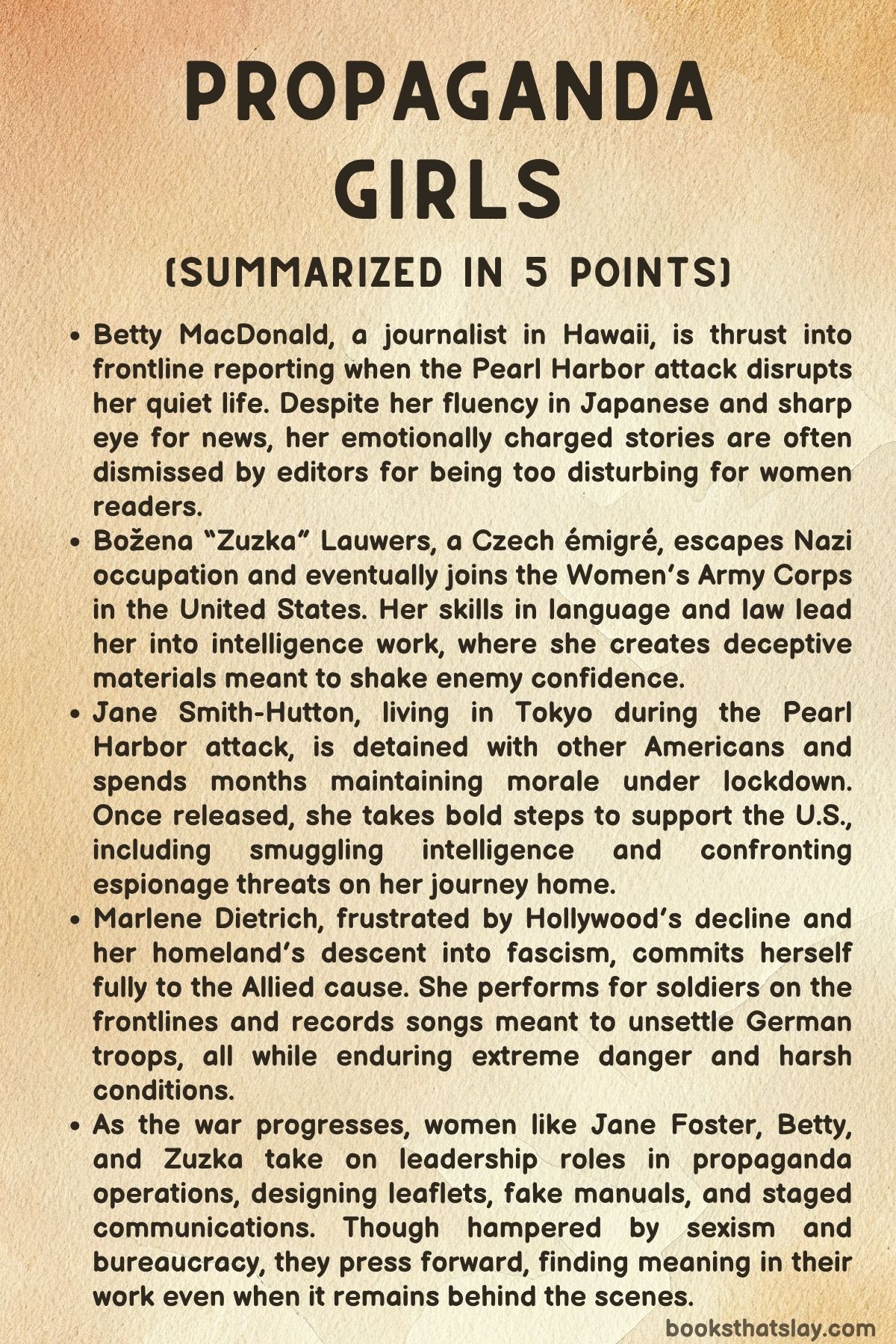

Propaganda Girls:The Secret War of the Women in the OSS by Lisa Rogak is a nonfiction book that brings to light the little-known yet deeply significant roles women played in psychological warfare during World War II. It focuses on a diverse group of courageous, skilled, and boundary-pushing women—journalists, actresses, intelligence agents, and creatives—who took on missions not with weapons, but with wit, language, and influence.

Through a blend of character study and historical storytelling, the book explores how these women navigated sexism, danger, and bureaucratic resistance to impact the war effort through propaganda, psychological operations, and cultural subversion. Their stories reveal both the visible and invisible contributions of women during a time of global upheaval.

Summary

Propaganda Girls opens on the morning of December 7, 1941, with Elizabeth “Betty” MacDonald, a Honolulu society editor, waking to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Trained in journalism and fluent in Japanese, Betty longed for meaningful news stories and rushed to the devastation with a photographer.

Amid the chaos, she orchestrated a photo of a crying boy that later appeared in Life magazine. Though her editor censored her firsthand hospital accounts as too distressing, she persisted.

Betty contributed to the war effort by volunteering locally and, after her husband joined the Navy, she began reporting for the San Francisco Chronicle, though she remained frustrated by the limitations placed on women in journalism.

Simultaneously, Božena “Zuzka” Lauwers, a Slovakian woman raised in Brno, fled the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia after marrying Belgian-American Charles Lauwers. The couple escaped through Africa and ultimately landed in New York.

There, Zuzka began ghostwriting for the Czech embassy and later penned a book under a colonel’s name. Determined to serve actively, she joined the Women’s Army Corps, took on the name Barbara, and became a U.S. citizen.

Her skill set and boldness made her an ideal candidate for intelligence work.

Meanwhile, in Tokyo, Jane Smith-Hutton found herself trapped after Pearl Harbor. Married to a diplomat, Jane endured six months of confinement by Japanese military police at the U.S. embassy.

She documented life in captivity and boosted morale among the detainees. After being released in a diplomatic exchange, she helped smuggle information back to the United States and supported Allied efforts with zeal.

In the next chapters, Marlene Dietrich emerges as a faded film star finding new purpose in opposing fascism. She rejected Nazi propaganda overtures and became an American citizen.

Her humanitarian instincts and opposition to Hitler fueled her efforts to help refugees and later led her to serve with the OSS. Her contributions would evolve into powerful propaganda campaigns using music and radio broadcasts.

Zuzka, now embedded within the OSS, undertook psychological warfare operations from Rome. She was involved in Operation Sauerkraut, where German POWs were used to plant misinformation.

She oversaw the creation of fake newspapers, leaflets, and postcards meant to demoralize enemy troops. Her unorthodox methods, including a violent confrontation with a Nazi prisoner, demonstrated both her resilience and her willingness to take risks.

Betty’s journey took a similar turn when she joined the OSS’s Morale Operations division. Stationed in India, she struggled with the sexism and resource constraints typical of the time.

Still, her fluency in Japanese proved critical as she authored forged imperial documents, including a fake surrender order allegedly from Emperor Hirohito. These tactics led to genuine enemy surrenders and showcased her strategic thinking.

She used inventive delivery methods, like floating waterproofed leaflets on the sea, to reach enemy-held islands.

Marlene Dietrich reappears, reinvigorated by her bond with soldiers. She joined USO tours, performed under hazardous conditions, and even carried a pistol provided by General Patton during the Battle of the Bulge.

Beyond her stage presence, her participation in the OSS’s MUZAK Project, where she recorded melancholy German songs like “Lili Marlene,” targeted enemy morale. Though these broadcasts infuriated Nazi leadership, they left a mark on German listeners.

Marlene’s sense of duty eclipsed her former Hollywood life, and her voice became a subtle yet effective weapon.

The book then focuses on the bureaucratic challenges faced by Jane Foster and Betty McIntosh in their leadership roles within Morale Operations. Jane Foster led Project Marigold, which tapped into the talents of Japanese-American artists to create satirical propaganda.

Her team developed leaflets and publications that undermined military values and planted seeds of doubt. Despite her successes, Jane faced gender discrimination and systemic barriers, eventually resigning from her post, proud of her work but disillusioned by the lack of recognition.

Betty continued to push boundaries, grappling with the ethical complexity of her mission—crafting propaganda that could both save and destroy lives. She balanced creativity with calculated manipulation, all while navigating a male-dominated field.

Her efforts contributed to the psychological destabilization of Japanese troops, a factor that aided Allied victories in the Pacific.

Zuzka’s postwar life took a different direction. She helped revive Austria’s cultural scene by organizing the Salzburg Festival and later returned to her ravaged hometown in Czechoslovakia.

Her reunion with her surviving parents was bittersweet. After returning to the U.S. , she embraced American life fully.

She became a mother, resumed work in media, and eventually lent her voice to Voice of America, helping shape Czech-American relations until her passing in 2009.

Marlene, after the war, found civilian life unsatisfying. Though she returned to performing, her wartime experience had redefined her sense of self.

Her contributions to the Allied cause, which included enduring hardships on the front and bearing the scorn of her native Germany, became her proudest legacy. She never forgot the camaraderie she shared with soldiers and saw her wartime work as the most meaningful chapter of her life.

For Betty, the war’s end was equally disorienting. She found closure by assisting in the liberation of POW camps and eventually chronicled her experiences in her memoir Undercover Girl.

She married fellow OSS operative Richard Heppner, and although she briefly withdrew from professional life after his death, she later returned to government work. The war had reshaped her ambitions and solidified her belief in the power of words as instruments of resistance.

Across these narratives, Propaganda Girls spotlights the critical yet overlooked roles women played in manipulating morale, spreading strategic misinformation, and shaping wartime culture. They were writers, performers, and strategists who used intellect and innovation to confront totalitarianism.

Their impact did not come through traditional combat but through influence, deception, and psychological endurance. Their legacy lies in proving that the battlefield of minds is just as vital as the one of weapons—and that women belonged in both.

Characters

Elizabeth “Betty” MacDonald

Elizabeth “Betty” MacDonald emerges in Propaganda Girls as a fiercely determined and morally complex figure, driven by her passion for journalism and her hunger to report the truth. Initially constrained to soft news as a society editor in Honolulu, Betty feels stifled by the superficial trappings of luncheon reporting.

Her desire for more impactful storytelling is not just professional ambition—it’s a form of resistance against the gendered expectations of her time. The attack on Pearl Harbor becomes her defining pivot point, thrusting her into action as she races toward the devastation, capturing the now-infamous image of a crying child by deliberately provoking his tears.

This unsettling yet iconic moment speaks volumes about her complicated relationship with truth, ethics, and the power of imagery in wartime storytelling.

Betty’s later transition into psychological warfare through the OSS reveals her continued pursuit of high-stakes, influential work. Her Japanese fluency becomes a tool of propaganda as she writes forged decrees and misleading narratives intended to weaken Japanese resolve.

Her most notable success—a fake surrender order attributed to Emperor Hirohito—blurs the lines between deception and salvation. She is deeply aware of the moral cost of her work: the lives it may save, the deaths it may cause, and the ambiguity that lies between.

This tension haunts her after the war, when peace brings a loss of purpose rather than relief. Her emotional depth, professional resolve, and internal conflicts make her one of the most richly drawn characters in the book, standing at the intersection of journalism, espionage, and emotional truth.

Božena “Zuzka” Lauwers / Barbara Weinberger

Zuzka’s character is marked by intellectual independence, linguistic brilliance, and a tenacious rejection of traditional gender roles. Born in Czechoslovakia to rigidly conservative parents, she defies familial and societal norms by pursuing higher education and a career in advertising before WWII reshapes her trajectory.

Her whirlwind marriage and subsequent escape from Nazi-occupied Europe reveal her ability to adapt quickly and decisively in crisis. Reborn in America as “Barbara,” Zuzka brings her razor-sharp mind and command of multiple languages to bear in the U.S. military intelligence community.

Her role in the OSS’s Morale Operations division is perhaps one of the most daring of all the women profiled in Propaganda Girls. She doesn’t merely support psychological warfare—she shapes it.

Whether producing forged German newspapers or working on Operation Sauerkraut to manipulate enemy POWs, Zuzka thrives on intellectual risk and ideological confrontation. She faces not just bureaucratic sexism but also physical danger, as seen in her tense standoff with a Nazi prisoner.

Her postwar journey is equally profound. Returning to her bombed hometown and finding her parents alive offers her a moment of personal closure, but also a realization that home is now elsewhere.

As a broadcaster, mother, and cultural ambassador, Zuzka’s legacy extends well beyond the battlefield. She embodies both the personal and political consequences of war, carving out space for herself where few women dared to exist.

Jane Smith-Hutton

Jane Smith-Hutton is portrayed as a calm yet formidable presence, whose diplomatic experience, cultural fluency, and maternal instincts converge during one of the most precarious moments of WWII. Living in Tokyo before Pearl Harbor, Jane is more than just a diplomat’s wife—she is a keen observer of Japanese society, immersed in its language and customs.

When the Japanese military raids the U. S. embassy, she transforms from a passive bystander into an active orchestrator of morale and resistance. Her leadership during their internment is quiet but resolute: organizing games, maintaining a sense of dignity, and using her camera to document a chapter of history few outsiders would ever witness.

What distinguishes Jane is her psychological resilience and sense of duty. On the diplomatic ship returning to the U.S., she is already back to work—monitoring for spies and smuggling intelligence.

Her transition from interned diplomat to covert agent is seamless and driven not by vengeance, but by a moral imperative to contribute. Though she receives less institutional recognition than others, her work in morale operations—particularly Project Marigold—demonstrates her creative brilliance and resolve.

She also faces the crushing weight of bureaucratic sexism. Despite leading crucial initiatives and managing diverse teams, Jane is repeatedly denied advancement.

Her resignation is both an act of protest and a testament to the structural barriers faced by women in intelligence roles. Nonetheless, her narrative is one of bravery, grace under pressure, and an enduring sense of purpose.

Marlene Dietrich

Marlene Dietrich represents a stunning fusion of glamour, political defiance, and emotional authenticity. Once a luminous star of the silver screen, her career had begun to wane by the late 1930s, prompting her to redefine her identity not through celebrity, but through principled action.

Her categorical rejection of Nazi overtures and her renunciation of German citizenship make her a political exile by choice—one who sacrifices fame and homeland for ideology. Her commitment to the Allied cause is deeply personal, born from a disgust with fascism and a profound identification with democratic values.

Marlene’s contributions to psychological warfare are multifaceted. From her stirring USO performances on the front lines to her haunting renditions for the OSS’s MUZAK Project, she uses her voice—literally—as a weapon.

Her version of “Lili Marlene” becomes both a balm and a subversive tool, capturing the hearts of German soldiers while enraging Nazi officials. Dietrich’s persona, once marked by mystique and seduction, evolves into something rawer and more elemental: a weary voice singing through snow and blood to soldiers who see her as a surrogate for everything they left behind.

Her wartime service nearly costs her her life, and she carries a pistol in case of capture, underscoring her awareness of the personal stakes involved.

After the war, she struggles with a loss of purpose that acting can no longer fill. But she remains proud of her contributions, seeing them not as a detour from her career, but as its moral apex.

In Propaganda Girls, Marlene stands as a beacon of transformative patriotism—glamour wielded in service of resistance.

Jane Foster

Jane Foster’s narrative adds another layer to the tapestry of brilliant, under-recognized women in wartime intelligence. Operating in the OSS’s Morale Operations unit, she stands out for her innovative spirit and managerial skill.

As director of Project Marigold, she organizes the creative work of Japanese-American artists—many from internment camps—and channels their talents into producing razor-sharp propaganda. This includes doctored military manuals, children’s magazines, and black parodies of Japanese codes, all designed to fracture enemy morale.

Jane’s work is less about brute force and more about psychological finesse—using wit, satire, and visual irony to destabilize cultural certainties.

What complicates Jane’s story is her continuous confrontation with institutional sexism. Despite her success and creative leadership, she is systematically sidelined in favor of less capable male colleagues.

Her eventual resignation is a consequence of this frustration, a quiet but powerful indictment of the misogyny that pervaded even the most progressive wartime efforts. Yet she remains proud of her work, having contributed something uniquely effective to the war—artful dissent and imaginative sabotage.

Her legacy is not in medals or ranks, but in the moral and psychological victories she enabled through intelligence and creativity.

Themes

Women Subverting Gender Norms in Wartime Roles

Throughout Propaganda Girls, the women at the heart of the narrative repeatedly challenge and exceed the societal limitations placed on them due to gender. Betty MacDonald’s desire to break out of “soft news” and cover serious, on-the-ground war reporting is emblematic of this rebellion.

Her editors continually stifle her contributions, assuming women cannot or should not digest harsh realities, yet Betty’s determination overrides their constraints. She inserts herself into dangerous scenes and ultimately transitions into a psychological warfare agent—roles traditionally reserved for men.

Similarly, Zuzka’s transition from Czech refugee to an integral figure in the OSS’s black propaganda efforts illustrates an active disruption of the passive female role. Her linguistic prowess, adaptability, and commitment lead her to participate in missions involving disinformation and POW manipulation—domains dominated by men and considered dangerous.

Marlene Dietrich, too, refuses to be merely ornamental. Rather than accept an easy role as a figurehead of morale or be co-opted by Nazi propaganda, she asserts herself as a symbol of resistance, weaponizing her artistry and identity for Allied objectives.

Even Jane Foster, working within the Morale Operations division, contends with bureaucratic sexism that bars her from promotion despite demonstrable leadership. Their stories create a pattern: women defying traditional domestic or ornamental roles by seizing positions in espionage, propaganda, and combat-adjacent zones.

These roles were not offered—they were demanded, often at great personal cost. Collectively, they expose how the war became both a stage for extraordinary service and a crucible for testing the boundaries of womanhood.

The Power and Moral Ambiguity of Propaganda

The use of psychological warfare, particularly through black propaganda, emerges as a central thematic tension in Propaganda Girls, revealing both its strategic necessity and its moral complexity. Propaganda is portrayed not merely as a supplemental tool but as a powerful weapon capable of shifting the momentum of war.

Betty’s forged imperial edict, which results in actual Japanese surrenders, demonstrates the immediate tactical efficacy of deception. The forged materials, be they fake newspapers or manipulated manuals, destabilize enemy morale and sow confusion behind enemy lines.

However, these acts carry a profound ethical weight. Betty herself is haunted by the possibility that her misinformation could lead to deaths or manipulation on a massive scale.

The line between saving lives and orchestrating suffering becomes blurred. Marlene’s participation in the MUZAK Project also brings this theme to the fore.

Her emotional renditions of altered German songs serve as subtle forms of psychological sabotage, manipulating nostalgia and homesickness to erode soldier confidence. In Jane Foster’s work directing interned Japanese-Americans to craft anti-Japanese material, the contradiction of exploiting those harmed by American policy for American ends adds another layer of ethical dissonance.

The book never simplifies propaganda into a force of good or evil but rather presents it as a deeply human undertaking—one filled with rationalizations, justifications, and regret. This theme captures the double-edged nature of influence and persuasion during wartime, suggesting that winning minds can be as morally fraught as winning battles.

Identity, Reinvention, and Personal Transformation

Propaganda Girls continuously explores how wartime necessity forces the women in the narrative to reevaluate, reconstruct, and sometimes wholly reinvent their identities. These transformations are rarely cosmetic—they are existential shifts dictated by survival, ambition, and purpose.

Zuzka’s journey from Czech lawyer to American intelligence officer involves multiple name changes, linguistic adaptations, and a complete overhaul of her personal and professional identity. She takes on the name “Barbara” for bureaucratic convenience, but the change signals a deeper transition from displaced refugee to active agent of change.

Betty MacDonald similarly transitions from society reporter to government operative, adopting new ethical frameworks and skill sets that diverge radically from her earlier persona. Her capacity for emotional detachment and moral calculation grows in tandem with her role in the OSS.

Marlene Dietrich’s transformation, though less about professional shift and more about self-definition, is no less profound. Her renunciation of German citizenship is not simply a political act but a rejection of heritage and a reinvention as an artist-soldier.

These women redefine themselves not in reaction to men but in response to global conflict, asserting autonomy over who they are and what they represent. Their identities become tools of war, fluid and functional, yet grounded in deeply personal convictions.

This theme underscores how extreme conditions challenge fixed notions of self, enabling new forms of agency and purpose to emerge.

Sacrifice and the Emotional Cost of War

While heroism is visible in the actions of the women portrayed, Propaganda Girls also emphasizes the long-lasting emotional and psychological toll their wartime efforts exact. The trauma they experience is rarely recognized or honored in real-time, and their sacrifices often lead to postwar isolation or existential emptiness.

Marlene Dietrich’s disillusionment with postwar entertainment speaks volumes about the gap between wartime meaning and peacetime banality. Her efforts during the war were met with public backlash from her homeland and private exhaustion from physical and emotional strain, yet they became the defining period of her life.

Betty, too, feels hollow in the postwar years. The adrenaline, moral clarity, and urgent purpose of wartime are replaced by domestic losses and a sense of irrelevance.

She finds fleeting peace only in helping liberate POW camps—tasks that resonate with her deep need to feel useful in a shattered world. Zuzka’s return to Brno, while joyful in the reunion with her parents, is also marked by a rupture in belonging.

Her war-forged identity as an American intelligence agent cannot be reconciled with the ruins of her past. These emotional reckonings reveal that the costs of service are not limited to the battlefield.

They are endured in silence, in dislocation, and in the loss of a prior self. The theme resists triumphant resolution, instead portraying sacrifice as complex, necessary, and deeply wounding.

Patriotic Defiance and Personal Agency

One of the most compelling undercurrents throughout Propaganda Girls is the recurring choice to resist through personal conviction, often in opposition to institutional or national expectations. These women do not conform to their governments or societies blindly; they challenge, resist, and often operate at the margins to assert their own vision of justice and patriotism.

Marlene Dietrich’s refusal to support the Nazi regime despite repeated overtures from Goebbels is a bold statement of ideological rejection. She chooses exile, public scorn, and even danger at the front lines over compliance.

Zuzka’s declaration that she would join the military if a male colleague refused embodies a similar spirit of defiance—an active reclaiming of agency in the face of apathy. Jane Foster works around internment injustices by recruiting Japanese-American artists to contribute to anti-Axis propaganda, using creativity to both resist enemy ideology and reclaim dignity for the oppressed.

Betty challenges her editors, her colleagues, and even military hierarchy to ensure her voice is heard and her skills put to use. Their brand of patriotism is never performative.

It is shaped by thoughtful dissent, personal risk, and an unrelenting desire to shape outcomes rather than be passively shaped by them. The theme underscores how true allegiance can often involve saying no—no to injustice, to exclusion, to silence—and how such refusals can be powerful forms of resistance.