Say a Little Prayer Summary, Characters and Themes

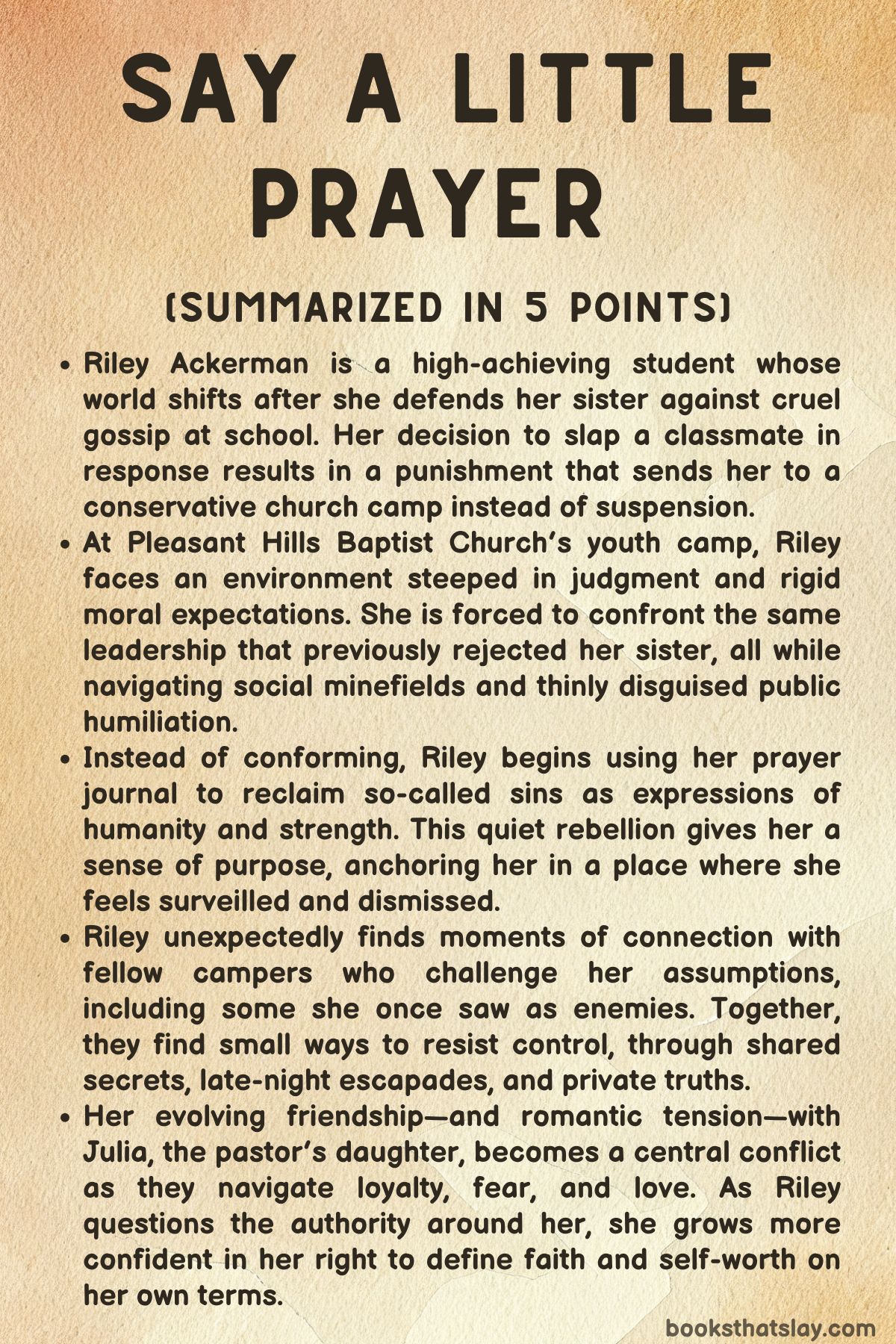

Say a Little Prayer by Jenna Voris is a sharp, emotionally charged coming-of-age novel about a queer teenage girl who dares to challenge the sanctity of religious hypocrisy. Set against the backdrop of a conservative church camp in the American South, the story follows Riley Ackerman as she navigates punishment, faith, shame, and the power of resistance.

Her journey is both deeply personal and strikingly political, exploring how institutions use dogma to marginalize, silence, and control. With biting humor and raw vulnerability, the novel delivers a nuanced portrayal of courage, community, and reclaiming one’s voice in a world that demands conformity.

Summary

Riley Ackerman, a high school overachiever and dedicated theater kid, finds herself in the principal’s office—not to be celebrated, but to face consequences after slapping her classmate Amanda Clarke. Amanda had cruelly mocked Riley’s older sister, Hannah, who was publicly shamed and alienated from their religious community after having an abortion.

In a school steeped in performative kindness and Christian platitudes, Riley’s act of violence is condemned, even as Amanda’s provocation is overlooked. Principal Rider, while acknowledging Riley’s academic record, insists she must face discipline.

When Riley begs not to miss Shrek the Musical’s tech week—her first starring role—he offers a compromise: instead of suspension, she must attend a weeklong church camp and write a reflective essay.

Riley, reluctant but determined not to lose her role in the show, agrees. But Pleasant Hills Baptist Church, the camp’s sponsor, is the same institution that turned its back on Hannah.

Pastor Young, the church’s domineering leader, once shamed Hannah from the pulpit, and Riley has never forgotten it. As she prepares for camp, Riley vents to Hannah, who supports her but reminds her not to lose herself in the system that rejected them.

Riley’s friends, Julia and Ben—Pastor Young’s children—try to be supportive, but the weight of Riley’s unease grows heavier as camp approaches.

Upon arriving at camp, Riley is met with rigid rules, confiscated phones, and thinly veiled efforts at public shaming cloaked as prayer. She is placed in a cabin with Amanda and Greer, adding to her sense of isolation.

The curriculum centers on resisting temptation and rejecting sin, taught through the lens of absolute morality. Pastor Young’s authority is absolute, and his sermons focus on guilt, fear, and conformity.

Riley quickly sees that this place is not about healing or community; it is about control.

Riley’s internal resistance begins to take shape. Rather than yielding to guilt, she questions the framework that defines sin and virtue.

She begins reimagining the seven deadly sins—not as vices, but as misunderstood aspects of human nature. Her camp essay becomes a manifesto, in which she examines how each sin can be an act of resistance or self-empowerment.

Sloth becomes rest in the face of burnout. Wrath becomes righteous anger against injustice.

Her journal entries reflect a growing awareness of how morality is weaponized, particularly against women and queer people.

She forms bonds with Delaney, a chaotic but supportive fellow camper, and even begins to soften toward Greer, who reveals her own regrets over abandoning Hannah. In secret acts of rebellion—watching banned movies, sneaking snacks, or skipping chores—Riley and her new friends push back against the camp’s control.

These small moments of defiance become acts of survival and solidarity.

Julia, Riley’s longtime friend and the pastor’s daughter, becomes a focal point of emotional tension. Their connection is deep, complicated by past feelings and unspoken truths.

Riley’s feelings for Julia simmer beneath the surface, surfacing in fleeting touches, long glances, and quiet acts of intimacy. Julia, caught between her loyalty to her father and her feelings for Riley, walks a tightrope of silence and complicity.

Despite this, she joins Riley on a thrift store outing—coded as an act of “greed”—and quietly supports her rebellion.

The emotional climax builds as Riley leads a secret kitchen raid during a camp-wide fasting ritual. Framing the act as a reclamation of gluttony, she and the other girls sneak into the kitchen and feast on forbidden food.

The moment is joyous and sacred, a communion of rebellion. Even Amanda, once Riley’s nemesis, joins in, revealing vulnerability and loneliness beneath her confident facade.

The event becomes a bonding experience, uniting girls who were once strangers or enemies.

Tensions boil over when Riley confronts Greer about her past betrayal of Hannah. Greer admits she acted out of fear—fear of being cast out, fear of the same judgment Hannah faced.

The acknowledgment doesn’t erase the hurt, but it begins a path toward understanding. A similar moment occurs between Riley and Amanda, who confesses to fabricating her college acceptance and failing in ways she was too ashamed to admit.

Their mutual destruction of ornaments—symbols of false perfection—serves as catharsis, an angry but honest truce.

After a storm forces the camp to end early, Riley returns home emotionally battered. She opens up to Hannah, admitting her confusion, guilt, and unresolved feelings for Julia.

Hannah offers comfort and insight, challenging Riley’s belief that she must be the strong one and validating her pain. This conversation helps Riley let go of the need to carry everything alone.

Determined to confront Julia, Riley attends a church event where Pastor Young publicly reads a queer confession found in a prayer journal—Julia’s journal—with the intent to shame its anonymous author. In a bold move, Riley claims it as her own to protect Julia.

One by one, her friends—Greer, Amanda, Ben, Delaney—stand and do the same, turning Pastor Young’s weapon against him. Julia finally confesses, outing herself and refusing to let Riley take the fall.

The group escapes to the bathroom where Julia and Riley reconcile. Julia admits her feelings and regrets, and the two share a kiss that affirms their relationship.

Prom night serves as a quiet epilogue. Riley and her friends, no longer bound by the church’s judgment, gather at Torres’s house to prepare for the dance.

Letters of excommunication arrive, but instead of breaking them, they bind the group closer. Riley and Julia skip the dance for Taco Bell, choosing joy and freedom over tradition.

As they kiss under the car’s dome light, Riley realizes that what she wants is not perfection or acceptance from others, but the right to define her own future.

In the end, Riley’s story is about refusing to be shamed into silence. She stands not just for herself, but for every girl taught that her body, love, or anger is a sin.

Say a Little Prayer becomes a declaration of spiritual independence—a quiet, furious act of faith in herself.

Characters

Riley Ackerman

Riley is the fierce, thoughtful, and emotionally complex protagonist of Say a Little Prayer. Her character arc traces a transformation from principled resentment to radical self-acceptance.

At the outset, Riley is a high-achieving theater student, proud of her academic and creative pursuits, yet emotionally burdened by the moral duplicity of her community. Her decision to slap Amanda Clarke, though impulsive, is driven by a deep sense of justice for her sister Hannah, who was publicly shamed after an abortion.

This act sets her on a collision course with Pleasant Hills Baptist Church and Pastor Young’s ideological dominion. Sent to a youth camp as punishment, Riley initially views it as a necessary evil to save her role in the school musical, but it evolves into something more transformative.

Her internal rebellion begins to take shape as she confronts institutional hypocrisy and crafts her own framework of morality by reinterpreting the seven deadly sins as virtues. Her relationship with Julia—tentative, longing, and painfully authentic—complicates her emotional landscape, revealing Riley’s deep need to be seen and loved for who she truly is.

Throughout the novel, Riley’s sharp wit, unwavering sense of justice, and capacity for love make her a magnetic and deeply empathetic character. By the end, she is no longer just reacting to the world around her; she actively reshapes it, defending Julia from public humiliation, reclaiming her faith on her own terms, and finding strength in vulnerability.

Julia Young

Julia is the quiet storm at the center of Riley’s emotional and spiritual upheaval. As Pastor Young’s daughter, Julia occupies a paradoxical space—she is both complicit in and victimized by the moral codes that govern Pleasant Hills.

Her closeness with Riley is tinged with romantic undercurrents and emotional longing, yet it is constantly obstructed by fear—fear of her father, her community, and her own identity. Julia’s gestures are subtle but loaded with meaning: helping Riley thrift-shop, squeezing her hand in bed, and finally confessing her love.

Her journey is marked by hesitation, internal conflict, and a slow-burning courage that culminates in her public coming out. Her arc is not as overtly defiant as Riley’s, but it is equally powerful.

In the end, Julia emerges as someone who chooses love and truth, even at the cost of familial acceptance. Her emotional reconciliation with Riley, especially in the safety of the women’s bathroom after the prayer book incident, is one of the most poignant moments in the novel, signifying healing, love, and mutual recognition.

Hannah Ackerman

Hannah, Riley’s older sister, is both a symbol of past trauma and a grounding force in Riley’s life. Ostracized by their church community after her abortion, Hannah bears the scars of public shame and spiritual condemnation.

Yet she refuses to be broken. Her character embodies quiet resilience and unconditional love.

She listens to Riley’s frustrations without judgment, pushes her sister to confront her feelings, and ultimately serves as a mirror for Riley’s own emotional burdens. In confronting Riley’s savior complex, Hannah helps dismantle the idea that strength is synonymous with silence or emotional suppression.

Her presence underscores the long-term consequences of religious ostracization and serves as a cautionary figure against internalized shame. At the same time, her support and honesty offer Riley a path to self-understanding and forgiveness.

Pastor Young

Pastor Young represents the oppressive institutional power that the novel critiques. He is a charismatic yet deeply manipulative figure, wielding religious rhetoric to enforce conformity and punish deviation.

His public shaming of Hannah, veiled condemnations of Riley, and final act of weaponizing a prayer book confession highlight his obsession with control. He operates through fear, conditioning others to equate obedience with morality.

Yet his power begins to wane when the very teenagers he seeks to dominate start resisting. In many ways, Pastor Young is less a character and more a looming ideological force—embodying the danger of unchecked authority masked as piety.

His silent presence at the bonfire, even after his public shaming tactic fails, reinforces his insidious influence, but it is also a turning point: he is no longer untouchable.

Greer

Greer begins the novel as a rule-follower, seemingly aligned with Amanda and the church establishment. Yet her character is more nuanced.

Her fractured past with Hannah and subtle acts of rebellion—like joining the kitchen raid—reveal a girl torn between fear and conscience. Greer’s eventual confrontation with Riley about Hannah’s abandonment is raw and illuminating.

She admits to her own fear of being cast out, revealing the emotional blackmail at the heart of the church’s social hierarchy. Greer is not naturally cruel; she is someone who has internalized the fear of exclusion so deeply that it governs her actions.

Her shift from passive bystander to quiet rebel is a testament to the power of solidarity and the complexities of guilt.

Amanda Clarke

Amanda is initially cast as the antagonist—a popular girl who gossips, lies, and gets Riley punished. However, as the story unfolds, she is revealed to be a deeply insecure and disillusioned figure.

Her lies about her college acceptance and her own feelings of alienation paint the picture of a girl who performs confidence but feels invisible. Her participation in the kitchen heist and her late-night confession to Riley—culminating in their joint act of destruction—transform her from a one-dimensional bully into a symbol of suppressed rage and brokenness.

Amanda’s arc reminds readers that complicity often masks pain and that even those who perpetuate harm can be victims of the system.

Delaney

Delaney is a refreshing force of chaos, humor, and loyalty in the emotionally charged landscape of church camp. She immediately bonds with Riley and becomes her co-conspirator in various acts of rebellion.

Delaney doesn’t need much convincing to join the kitchen raid or stand up to Pastor Young, and her actions are driven more by gut instinct than calculated resistance. Yet, she is no less brave for it.

Delaney’s humor and emotional intelligence make her a key member of Riley’s found family. She helps diffuse tension and reminds the others—especially Riley—that resistance doesn’t always have to be solemn.

Her unapologetic presence is vital to the narrative’s spirit of joyful defiance.

Ben Young

Ben, Julia’s brother and Pastor Young’s son, serves as a bridge between the two worlds. Though not central to the plot’s emotional core, his support for Riley and Hannah quietly undermines his father’s authority.

His character is marked by quiet rebellion and compassion. Unlike Julia, he doesn’t struggle as visibly with his loyalties, and his alliance with Riley’s family, especially Hannah, hints at a more inclusive future.

Ben’s significance lies in his refusal to inherit his father’s legacy and his willingness to support those cast out by the system he was born into.

Themes

Religious Hypocrisy and Moral Policing

In Say a Little Prayer, the most omnipresent and oppressive force is the culture of religious hypocrisy entrenched in the school and church community. Riley’s initial act of rebellion—slapping Amanda for her cruel comment about Hannah’s abortion—unfolds in an environment cloaked in moral superiority, where the hallways are lined with Bible verses and hollow kindness slogans.

This environment masks a culture that weaponizes religious ideals to control and ostracize rather than uplift. Figures like Principal Rider and Pastor Young represent institutions that cloak their actions in sanctimony while practicing blatant double standards, particularly toward women.

Riley’s punishment for standing up for her sister is severe, while football players are let off the hook for worse offenses, illustrating how moral judgment is selectively applied to reinforce patriarchal norms. Pastor Young’s platform is not just a pulpit but a stage for spiritual manipulation, casting shame as virtue and control as discipline.

The public reading of the queer confession during a sermon is a particularly harrowing moment, where he leverages his authority not to heal but to expose and punish. Throughout the narrative, the church is less a spiritual sanctuary and more a surveillance state, where virtue is performative and conformity is rewarded.

Riley’s journey becomes a resistance to this form of moral policing, as she sees the way religious authority has been twisted to silence people like Hannah, herself, and eventually Julia. The story critiques a faith community more concerned with appearances and control than with compassion, exposing how easily religion can be misused to hurt those most in need of love and support.

Queer Identity and the Right to Self-Definition

Riley’s sexuality is not just a subplot in Say a Little Prayer but the lens through which many of the book’s central conflicts unfold. Her love for Julia, her fraught relationship with the church, and her emotional battle with shame and pride are all rooted in her need to live truthfully in a community that insists she must remain hidden.

Riley’s queerness is never treated as something that needs resolving; rather, the tension lies in how others react to it. Her affection for Julia is tender and sincere, filled with emotional honesty even when it’s messy.

Their evolving dynamic—from childhood best friends to tentative romance—is continually tested by the fear of exposure. Julia’s internalized fear of being outed and her initial complicity with her father’s dogma wounds Riley deeply, reinforcing how silence can be as harmful as rejection.

But the story also allows room for evolution. Julia’s eventual public admission of her identity is a monumental act of bravery and a moment of shared redemption.

Together, they reclaim agency over their love, defining it outside the terms dictated by others. In a broader sense, Riley’s refusal to apologize for who she is—even under threat of excommunication—cements the novel’s commitment to queer resistance.

Her journey is not about seeking acceptance from oppressive institutions but rejecting their premise entirely. She carves space for her identity not within the church’s rigid framework, but against it, forging a spiritual and emotional compass rooted in love, solidarity, and truth.

Solidarity, Found Family, and Collective Resistance

One of the most powerful arcs in Say a Little Prayer is Riley’s gradual movement from isolation to solidarity. Initially thrust into camp as a disciplinary measure, Riley braces for a week of judgment and alienation.

However, through a series of emotionally charged and rebellious moments—sharing secrets, staging a midnight kitchen raid, and supporting one another through spiritual hunger—she forms deep bonds with campers like Delaney, Greer, and eventually even Amanda. These relationships are not built on shared dogma, but shared experiences of marginalization and resistance.

Delaney’s chaotic energy, Greer’s guilt over abandoning Hannah, and Amanda’s emotional unraveling all reflect different forms of struggle within the same oppressive system. These girls do not band together because they are alike, but because they recognize each other’s pain and choose empathy over judgment.

Their midnight feast becomes an act of spiritual reclamation—a way to create joy and communion in a place designed to suppress both. The climactic moment when multiple girls and boys stand up in church to claim responsibility for Julia’s confession is the novel’s emotional high point.

It is an act of collective defiance that strips Pastor Young of his power and reframes shame as solidarity. This theme underscores that healing and justice are not achieved through individual martyrdom, but through mutual recognition and support.

Riley’s found family does more than shield her from harm—it empowers her to speak her truth and demand better from those around her.

Anger as a Form of Healing and Resistance

In many traditional narratives, anger is something to be tempered or overcome, especially for young women. Say a Little Prayer turns that expectation on its head by treating Riley’s anger as justified, cathartic, and ultimately transformative.

Her slap, her outbursts, and her righteous fury are not signs of immaturity but clear, human responses to profound injustice. Riley’s anger is not born of impulsivity but from a deep well of betrayal—by her school, her church, and even her friend Julia.

Her journal entries become a conduit for that rage, reframing each of the seven deadly sins as tools of survival rather than damnation. When she writes about wrath, it’s not to condemn it but to assert her right to feel it.

The moment she and Amanda smash glass ornaments together is especially potent: it’s a release of shared pain and a reclaiming of narrative control. For Amanda, who had maintained an armor of superiority, this act is a collapse of pretense.

For Riley, it’s a declaration that her emotions are valid. The story refuses to sanitize her emotions, instead honoring them as a necessary part of her coming-of-age.

Even the adults—particularly Pastor Young—fear her anger because it represents a challenge to their control. But Riley’s wrath is never directionless.

It is aimed squarely at hypocrisy, manipulation, and injustice. It gives her the fuel to stand up in church, to protect Julia, and to articulate her identity on her own terms.

Her anger is not what destroys her faith; it is what purifies it.

The Injustice of Institutional Power

Throughout Say a Little Prayer, institutional authority—whether in the form of the school system, the church, or even the family—is consistently depicted as fallible and self-interested. Principal Rider’s selective discipline, Pastor Young’s performative sermons, and even Julia’s mother’s willful ignorance all point to a system that prioritizes control over compassion.

Riley, Hannah, and the other girls are consistently told to “choose kindness” while being subjected to harsh judgment, double standards, and exclusion. These institutions thrive on appearances and obedience, expecting young people to remain silent and pliant in the face of real emotional trauma.

Hannah’s ostracization following her abortion is particularly damning: a church that preaches forgiveness and grace turns its back on her when she needs it most. Pastor Young, cloaked in religious authority, becomes the embodiment of this hypocrisy, using his pulpit to maintain his dominance rather than to minister.

Even Riley’s initial willingness to compromise—for the sake of her theater role—illustrates how institutional power co-opts ambition and passion, weaponizing it against individual conscience. But the book also shows how this power can be dismantled.

Through small acts of rebellion, shared vulnerability, and collective resistance, the characters chip away at the illusion of institutional infallibility. By the end, letters of excommunication have become badges of honor, and Riley no longer seeks the validation of a system that failed her.

The message is clear: real power comes not from titles or rituals, but from the courage to confront injustice, even when it wears a halo.