Saving Five Summary and Analysis | Amanda Nguyen

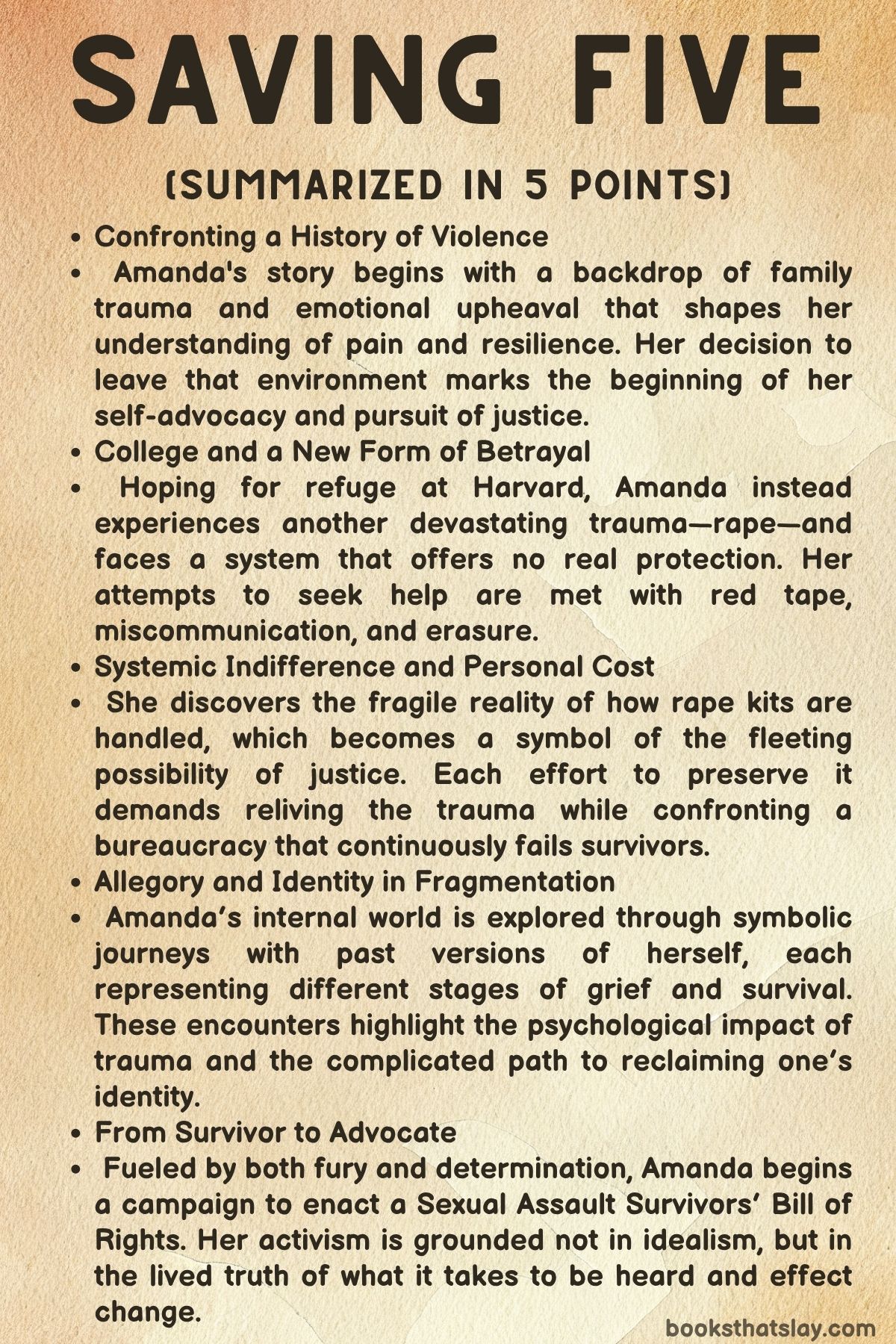

Saving Five: A Memoir of Hope by Amanda Nguyen is a courageous, intricate memoir that navigates the terrain between personal trauma and public activism. Blending psychological realism with symbolic imagination, Nguyen tells the story of surviving rape while a student at Harvard and the subsequent battle to preserve her rape kit—an experience that catalyzes her transformation from victim to legislative advocate.

The book is not just a record of events, but a vivid reckoning with memory, identity, grief, and justice. Moving between intimate personal experiences and the complex world of political advocacy, Nguyen’s account is as much about healing and survival as it is about the tenacity required to reform broken systems.

Summary

Amanda Nguyen’s story begins with the pain of her family life, shaped by emotional abuse and violence. Her childhood is defined by her father’s volatility and her mother’s unpredictable mental state.

During one explosive episode, Amanda’s mother threatens suicide and harms herself during an argument, forcing Amanda to confront the dysfunction that has shaped her upbringing. This rupture ends her connection to the home she knew and sparks the emergence of a new, self-protective identity.

When Amanda begins college at Harvard, she sees it as a place of refuge from her family. But it becomes the setting of another violent betrayal—her rape.

After following all the steps survivors are advised to take—submitting to a rape kit, contacting the police, reporting the assault—she finds herself entangled in a legal and medical system that dehumanizes victims and renders their pain invisible. Her rape kit, the very foundation of her pursuit of justice, is set to be destroyed within six months unless she herself ensures its preservation.

The realization that her right to justice is contingent on a bureaucratic clock sends her into a spiral of obsession and determination. She begins counting every minute left on her rape kit’s existence, understanding it not just as evidence, but as a symbol of the system’s failure to value survivors.

Amanda becomes consumed by the effort to preserve her kit. She calls forensic labs and police departments, only to be misled, dismissed, or stonewalled.

She discovers the responsibility for ensuring the preservation of her own evidence falls entirely on her. The process is costly, emotionally exhausting, and retraumatizing.

Every six months, she must revisit the crime—not only in memory, but in paperwork, legal forms, and renewal fees. This cycle of trauma becomes unbearable, yet she refuses to surrender.

Simultaneously, Amanda is attempting to build her professional future. She’s undergoing the intense interview process for the CIA, where disclosure of legal proceedings related to her rape would jeopardize her candidacy.

She is placed in a no-win scenario: pursue justice at the cost of her career, or suppress her truth in order to move forward. The situation illustrates the systemic cruelty survivors face—punished for demanding justice, forced to choose between healing and ambition.

Amid this chaos, Amanda finds strength in relationships. Friends like Alex and Mark offer moments of normalcy and comfort—washing her bedsheets, taking her for ice cream.

Professor Diane Rosenfeld becomes a guiding force, introducing Amanda to the social model of bonobos—female primates who collectively resist male dominance. This idea of a sisterhood founded on solidarity and mutual protection reshapes Amanda’s understanding of empowerment.

It becomes the conceptual backbone for her next step: organizing not just for herself, but for all survivors.

The memoir shifts into a dual mode—one part reality, one part internal allegory. Amanda imagines herself split into versions across time: the child (5), the teenager (15), the survivor (22), and the adult advocate (30).

These identities interact, mourn, fight, and grow together in surreal landscapes that represent emotional terrain. They travel through storms, deserts, and lighthouses, encountering personifications of emotions such as Anger, Sadness, and Acceptance.

The allegorical arc gives shape to Amanda’s internal healing, showing how trauma fragments the self and how memory, when faced with honesty and love, can be integrated rather than erased.

In the real world, Amanda begins drafting a Survivors’ Bill of Rights. Her legislative journey is filled with roadblocks: congressional apathy, performative politics, and even sabotage from supposed allies.

A Senate aide named Chad becomes the face of this betrayal, attempting to hijack the bill for credit while coercing Amanda into silence. She counters this manipulation by recording his threats, using them to ensure the bill’s passage.

Her activism, while noble, is never easy. She experiences exploitation and burnout, and is forced to relive her trauma in public spaces.

Yet her perseverance eventually bears fruit. Her bill is passed, providing essential protections for sexual assault survivors nationwide.

The moment of legislative victory is bittersweet. Amanda stands at the Lincoln Memorial, reflecting on the distance she has traveled—from the helpless girl counting stars on the curb, to the woman who convinced a nation to recognize her rights.

She rejects the idea of naming the legislation after herself, understanding the importance of collective identity. Her final cathartic moment is not in the halls of power but in solitude, where she cries, screams, and releases years of contained pain.

Her breakdown is also a rebirth, an acceptance of her full self—not as broken or heroic, but as real.

In the epilogue, Amanda achieves something once unimaginable: becoming the first Southeast Asian woman to travel to space aboard a Blue Origin mission. With her she carries a sign that reads, “Never Never Never Give Up.

” This phrase, once whispered to herself in despair, becomes a declaration etched into both legal history and the sky. Through this symbolic act, she reminds readers that survival, advocacy, and healing are not linear but interconnected.

Saving Five closes with Amanda no longer fragmented, but whole—every version of herself finally seen, heard, and held.

Key People

Amanda Nguyen

Amanda Nguyen, the central figure of Saving Five, emerges as both narrator and protagonist of a memoir that fuses emotional depth with political urgency. Her character is shaped by a multiplicity of identities—survivor, activist, daughter, astronaut, and advocate—each forged in the crucible of trauma, injustice, and resistance.

At the story’s core lies her experience of sexual assault while attending Harvard and the indifference she encounters from the very systems designed to deliver justice. This defining trauma becomes the ignition for Amanda’s metamorphosis from a young woman grappling with grief and silence into a relentless agent of change.

What distinguishes Amanda’s character is not only her resilience but her extraordinary capacity for transformation. She does not merely seek healing for herself but turns her anguish into legislative action, catalyzing change through the Survivors’ Bill of Rights.

Her refusal to accept symbolic victories—rejecting the name “Amanda’s Law” for broader representation—reinforces her selfless and collective vision of justice.

Amanda’s psychological landscape is as rich as her public actions are powerful. Through allegorical dreamscapes and fragmented memory, she interacts with different versions of herself—5, 15, 22, and 30—each representing phases of innocence, anger, grief, and wisdom.

These inner selves are not mere flashbacks but active participants in her journey, reflecting the profound emotional fragmentation that trauma inflicts. Yet Amanda’s ability to integrate these selves into a coherent identity speaks to her growth and self-reclamation.

Her rage, once overwhelming, becomes righteous; her grief, once splintering, becomes the groundwork of empathy and resolve. Even in moments of vulnerability—such as collapsing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial—Amanda exhibits a rare courage to be wholly seen, to break down and, in doing so, to rise anew.

The book’s final note, where she becomes the first Southeast Asian woman in space carrying the message “Never Never Never Give Up,” enshrines Amanda not only as a survivor but as a cultural symbol of transcendence, radical hope, and purpose-driven defiance.

Amanda at Age 5

The version of Amanda known as “5” represents lost innocence and the earliest spiritual bruises of her life. This iteration of her psyche is defined by confusion, tenderness, and an instinct to believe in safety even when it is routinely denied.

She is the embodiment of a child seeking comfort in a dangerous world—a world shaped by parental abuse, gendered disappointment, and emotional neglect. Her clinging to idealized memories, even when they prove false, underlines how trauma often roots itself in fantasy as a defense mechanism.

Amanda as 5 is not just a figure of innocence, but one of deep symbolic power. When she becomes the representation of “Acceptance” by the book’s end, it signals Amanda’s profound psychological reconciliation: the part of her most damaged is also the part that offers peace.

This child-self, once lost in grief’s labyrinth, becomes the compass guiding Amanda’s healing.

Amanda at Age 15

Fifteen-year-old Amanda stands as the bridge between naiveté and awareness. She is shaped by the rage of betrayal and the dawning recognition that her world—home, family, and gendered expectations—is neither safe nor fair.

She embodies the anger that erupts when illusions of protection crumble. In the allegorical arc, she is often reactive, volatile, and heartbroken, especially after the disappearance of 22 into the sea.

Her volatility mirrors the teenage struggle to process injustice with limited tools. Yet 15 is not simply angry—she is perceptive.

She voices truths that Amanda at 30 often suppresses. Her presence in Amanda’s inner journey is essential not only because she names the betrayal of family and culture but because she refuses to allow those betrayals to be glossed over.

Though not yet wise, 15’s refusal to forget or forgive prematurely becomes a necessary stage in Amanda’s evolution.

Amanda at Age 22

Amanda at 22 is the version closest to the moment of rupture—the rape and its immediate aftermath. She is analytical, detail-oriented, obsessed with the countdown to the rape kit’s destruction, and yet emotionally paralyzed.

She serves as a mirror of Amanda’s attempt to control chaos through logic, to extract meaning from bureaucratic indifference, and to impose order on a world that offers none. Her burden is tremendous: she carries not only fresh trauma but the responsibility of deciding whether to stay silent or risk everything in pursuit of justice.

Her strategic thinking—seen in her dealings with law enforcement and her near admission to the CIA—contrasts sharply with her internal fracturing. The loss of 22 to the sea in Amanda’s inner allegory is poignant, signifying the part of Amanda that was almost lost to despair and emotional shutdown.

Yet this disappearance also represents transformation: the end of a chapter where strength was defined by survival, and the beginning of one where strength is defined by advocacy.

Amanda at Age 30

Amanda at 30, the present-day self who narrates much of Saving Five, represents synthesis and reckoning. She is both the culmination of all her younger selves and the voice striving to hold them together.

At 30, Amanda has accumulated wisdom through suffering, strategy through setbacks, and clarity through chaos. Her return to Harvard for her ten-year reunion, her standing at the Lincoln Memorial, and her reflections in the Capitol define her as a woman deeply aware of her place in history—personal, political, and symbolic.

She balances grief with determination, activism with introspection. Unlike her younger selves, who often lived in reaction to trauma, Amanda at 30 lives in deliberate response.

She leverages trauma not as a weight but as a lever. Her decisions are guided by both lived experience and visionary ideals.

This Amanda is unafraid to be seen, unafraid to break, and ultimately unafraid to lead.

Melanie

Melanie, another survivor Amanda meets during her healing process, represents the sacred power of solidarity. Though her appearances are limited, her impact is profound.

Melanie functions as a grounding presence—one who understands without the need for explanation. In a world that often silences or disbelieves survivors, Melanie affirms Amanda’s truth through shared experience.

Their friendship signals that healing is not a solitary endeavor; it requires witnessing, companionship, and the comfort of being fully understood. Melanie also symbolizes the broader network of survivors who have endured, resisted, and quietly rebuilt their lives in the aftermath of violence.

She is a reminder that resilience is not exceptional—it is, tragically, common among those society has failed.

Diane Rosenfeld

Diane Rosenfeld, a Harvard Law professor, serves as a mentor and intellectual anchor for Amanda. Her introduction of the bonobo metaphor—female primates who protect each other from male violence—resonates deeply and provides Amanda with a new framework of empowerment.

Diane is not simply an academic; she is a kind of revolutionary maternal figure, offering tools of interpretation, sisterhood, and resistance. Her role is pivotal in helping Amanda transition from isolated suffering to strategic activism.

Diane’s support legitimizes Amanda’s mission and connects her to a broader lineage of feminist legal advocacy. She embodies the potential of institutions—when inhabited by the right people—to become sites of transformation rather than harm.

Chad

Chad, a junior Senate aide, is the embodiment of political opportunism and systemic gaslighting. While he initially appears to be a gatekeeper to legislative progress, he quickly reveals himself as a saboteur.

By attempting to take credit for Amanda’s work, silencing her voice, and introducing the bill as a performative stunt, Chad exemplifies how even well-meaning legislation can be co-opted by those seeking power rather than justice. His manipulation and coercion threaten to undo Amanda’s progress, making him not just an antagonist but a symbol of institutional betrayal.

Amanda’s ultimate triumph over Chad—recording his threats and outmaneuvering him—serves as a crucial reversal of power. It is not merely a personal victory but a reminder that truth, when wielded strategically, can unmask corruption and compel accountability.

Amanda’s Parents

Amanda’s parents—particularly her father—are haunting presences throughout Saving Five, representing the first betrayal Amanda ever experiences. Her father is physically and emotionally abusive, a patriarch who equates value with gender conformity and obedience.

Her mother, though also a victim of generational trauma and displacement, is complicit in Amanda’s suffering by her silence and inaction. The violence and neglect Amanda experiences at home foreshadow her later encounters with systemic violence in the justice system.

Yet, the memoir also acknowledges the complexity of her parents’ histories—refugees, survivors in their own right—adding layers to their portrayal. Amanda’s eventual confrontation with them is both literal and symbolic: a breaking away from inherited cycles of silence and shame, and a step toward reclaiming her own narrative.

Their presence in her inner world, particularly during her lowest moments, underlines how family trauma often lays the foundation for later wounds and how healing requires confronting not only what was done to us, but who we once needed and never had.

analysis of Themes

Bureaucratic Betrayal and Systemic Injustice

Amanda’s experience illustrates how bureaucracy, rather than being a neutral apparatus of justice, often becomes a source of secondary trauma. After enduring the violence of rape, she is thrust into a system where her identity is systematically stripped away.

The case name, “Commonwealth vs. the perpetrator,” displaces her from the narrative of her own suffering.

This bureaucratic distancing becomes even more brutal through the absurd hurdles she must navigate just to preserve her rape kit. The six-month expiration on unrequested preservation is not just a policy oversight—it represents a moral failure.

Amanda’s obsession with the ticking clock encapsulates the cruelty of a system that places the burden of maintaining evidence on the survivor. This transforms the justice system into a theater of cruelty, where victims are not supported but constantly retraumatized by cold procedures, fragmented communication, and institutional indifference.

Amanda’s phone calls, appeals, and frantic efforts to locate, verify, and protect her evidence demonstrate that the administrative machinery operates more to protect itself than to seek justice. The bureaucracy doesn’t simply fail her; it makes her responsible for navigating its maze at the worst moment of her life.

And when she steps into political advocacy, the pattern continues. Legislators tokenize her trauma, use her bill for public image management, and stall substantive change.

The reality that fewer than one percent of bills pass reinforces the farce. The system is not broken—it is working exactly as designed, for those it was designed to protect.

Amanda’s story shows how legal and governmental institutions often replicate the very violence they claim to remedy.

Fragmentation of Self and the Psychology of Trauma

The inner journey that Amanda embarks upon is not a metaphorical device but a precise psychological map of trauma’s impact on the self. Her mind fractures into distinct identities—5, 15, 22, 30—each representing specific developmental milestones marred by abuse, shame, and survival strategies.

This fragmentation is not symbolic whimsy; it’s an honest expression of how trauma dislocates identity. The five-year-old clings to imagined safety, the fifteen-year-old lashes out in pain, the twenty-two-year-old embodies raw rage, and the thirty-year-old carries the wisdom of scars.

These selves do not merely coexist; they struggle, argue, and resist integration, echoing the dissociative survival mechanisms that many trauma survivors endure. The surreal landscapes—stormy seas, memory vaults, sadness’s lighthouse—are psychological terrains.

Sadness tells her that sorrow lies not in pain itself but in love’s absence. That statement frames grief not as weakness, but as a capacity to remember what was once meaningful.

When Amanda must choose whether to abandon her inner child or carry her forward, it is a decisive moment that mirrors the psychological choice between repression and acceptance. Her survival hinges on uniting these selves—not by erasing them, but by honoring their truths.

Her final recognition of the child-self as the embodiment of Acceptance suggests that healing is not found in denial or strength alone, but in softness, remembrance, and a quiet, hard-won peace. The fractured self, when seen and heard, becomes whole again—not through linear progression, but through compassion across internal time.

Grief, Memory, and Generational Pain

Grief permeates Amanda’s narrative—not just the grief of personal violation, but of legacy, family, and unrealized safety. Her upbringing is marked by a fraught lineage of pain: a father bearing hidden trauma, a mother marked by the refugee experience and cultural silence, and a childhood home laced with emotional and physical volatility.

Amanda’s mother’s suicide threats, her father’s violence, and the generational expectations placed on her frame her trauma within a broader context of inherited suffering. Grief in Saving Five is shown to be both individual and ancestral, an emotional inheritance passed down silently but deeply felt.

Memory plays a dual role—sometimes oppressive, sometimes revelatory. It drags Amanda back into moments she would rather forget, but it also roots her to truth.

In Sadness’s lighthouse, she is told that memory is both gift and burden. This assertion helps Amanda understand that healing cannot occur through forgetting.

The act of remembering becomes radical: a confrontation with the past that breaks cycles of silence. When Amanda chooses to carry the memory of all her former selves into her future, she makes peace not only with her own story but with the generations before her who did not have that luxury.

By anchoring her grief in love rather than despair, she transforms inherited pain into a source of wisdom. Her advocacy, then, becomes not only an act of justice for herself and other survivors, but also a form of ancestral reparation.

Anger as Power and Catalyst

Anger is often dismissed as irrational or unproductive, especially when expressed by women or marginalized individuals. Yet in Amanda’s journey, anger is a vital and clarifying force.

When 22—the version of her most saturated with rage—disappears, Amanda must finally listen to the fury that she had tried to suppress, compartmentalize, or reframe. This anger is not just about her rape.

It stems from childhood neglect, institutional betrayal, gendered expectations, and cultural silencing. It is layered, old, and elemental.

The realm of Anger in the allegorical journey is a desert—not chaotic but scorched and barren, suggesting not a lack of control but a lack of nourishment. Amanda’s walk through this desert is not a loss of herself, but a confrontation with power denied.

Anger sharpens her resolve, fuels her policy battles, and helps her identify exploitation in political allies who treat her as a pawn. In the real world, Amanda’s ability to record Chad’s coercion and use it strategically is not cold logic—it is righteous fury transmuted into precision.

Her anger gives her the clarity to reject false peace and insist on meaningful change. It’s the engine behind her bill, her advocacy, and ultimately her healing.

Rather than being consumed by rage, she learns to wield it. Anger, in this narrative, is not merely an emotion but a tool—one that lights her path through darkness.

It becomes the fire that cauterizes wounds and illuminates the road to transformation.

Survival as Radical Defiance

Throughout Saving Five, survival is not portrayed as a passive state of endurance but as a radical and ongoing choice. Amanda’s refusal to give up—to abandon her rape kit, to be silenced by political opportunism, to accept the limitations imposed on her as a woman of color, a daughter of immigrants, a trauma survivor—is a form of defiance.

When she writes “Never Never Never Give Up,” it is not inspirational fluff. It is the manifesto of someone who has had to fight for every inch of ground beneath her feet.

Survival here is not just physical but legal, psychological, and existential. She has to survive the hospital, the police station, the courtroom, the Senate floor, and her own mind.

The decision not to drop out of the fight—even when pursuing the CIA might have offered comfort and anonymity—demonstrates that survival is about choosing purpose over escape. Amanda becomes an astronaut, not despite her trauma but because of the strength she has built through it.

That she carries her personal sign into space is not symbolic alone; it is an assertion of presence, of taking up space in a world that tried to erase her. Her very existence becomes an act of resistance.

The survivor narrative is often flattened into “she made it through. ” Amanda complicates that.

She survived not only by enduring, but by refusing to be reduced to what was done to her. Her survival becomes a declaration of selfhood, activism, and unstoppable momentum.