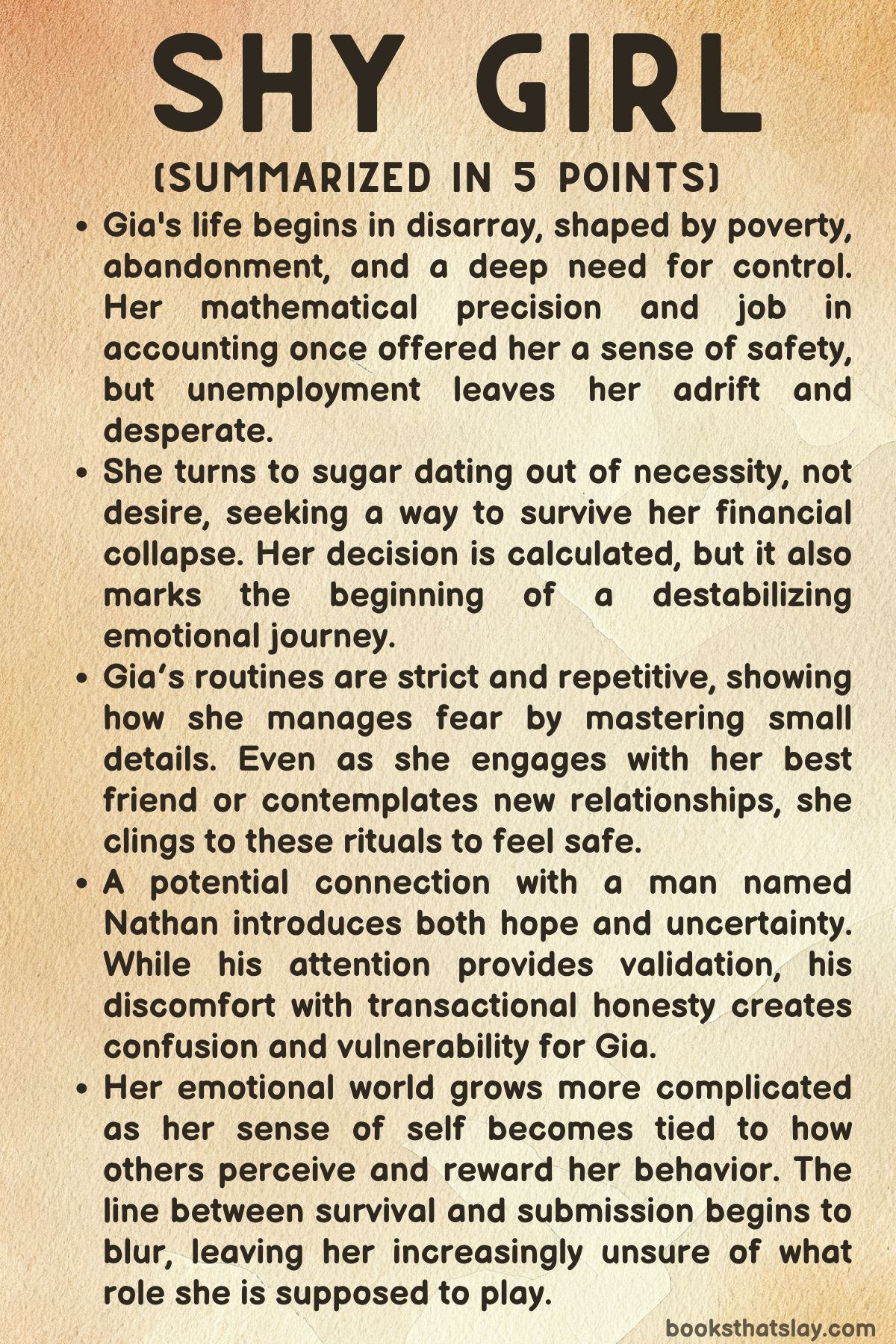

Shy Girl by Mia Ballard Summary, Characters and Themes

Shy Girl by Mia Ballard is a stark and harrowing exploration of captivity, identity erosion, and the psychological machinery of control. Told through the eyes of Gia, a woman crushed by economic instability and emotional abandonment, the novel traces her gradual transformation from a self-aware but desperate individual into a being stripped of autonomy and molded into the submissive ideal of her abuser.

Ballard uses Gia’s descent into pet-play and eventual imprisonment to comment on the dangers of survivalist compromise and how trauma rewires one’s sense of worth and freedom. Through a narrative that moves from desperation to dehumanization and finally to grotesque reclamation, Shy Girl forces readers to confront the terrifying consequences of erasure—both self-imposed and externally inflicted.

Summary

Gia is introduced in a state of extreme subjugation. The prologue features her locked in a humiliating pink dress, crawling and barking on command, forced to celebrate her own dehumanization with a birthday cake presented by her captor.

This disturbing scene sets the tone for a story where survival is bought at the price of dignity and where identity fractures under prolonged domination.

Rewinding to her past, we find Gia’s early life marked by abandonment and premature responsibility. Her mother left when she was six, and her father, though physically present, was emotionally vacant.

Forced into adult responsibilities too early, Gia latched onto mathematics as a tool for certainty and control, which later guided her into an accounting career. But when the pressures of adult life become too heavy and she loses her job, Gia is left with no emotional or financial buffer.

This disintegration of her structured world forces her to register on a sugar dating site—SDForMe. com—out of sheer economic necessity.

Her decision is confided to her best friend Kennedy, who surprisingly reacts with support, offering a flicker of understanding in an otherwise lonely existence. Still, Gia remains gripped by rigid daily routines, obsessively measuring and controlling every aspect of her life, from her oatmeal to her tears.

It’s a coping mechanism for a reality that feels increasingly unmanageable.

When Nathan contacts her through the site, the trajectory of Gia’s life takes a darker turn. He presents himself as polite and wealthy, but also evasive.

Gia becomes anxious yet hopeful, determined to impress and fulfill the expectations of this arrangement. Their first meeting at a lavish restaurant is both tense and revealing—Nathan exerts quiet dominance by ordering for her and ignoring her attempts to initiate personal conversation.

When she brings up financial matters directly, he is repulsed by her candor, instead claiming he wants something “real. ” The contradiction in his expectations leaves Gia confused and ashamed.

Eventually, Nathan invites Gia to his home. Once there, he introduces a collar and instructs her to bark and crawl, initiating her into a pet-play dynamic.

Gia complies, her submission fueled by desperation and the hope for financial stability. He offers her a more permanent arrangement: eight hours a day as his “dog,” in exchange for economic support.

Gia returns home and begins training herself—researching dog behavior, practicing movements, and seeking to perfect her obedience.

Her messages to Nathan reveal a stark power imbalance. She asks for permission to do basic things, and he responds with cold, clipped directions.

Her sense of self begins to dissolve. A visit to Kennedy’s well-ordered suburban life intensifies Gia’s feelings of inadequacy.

She smiles and nods through the visit, fully aware that she is about to return to a life not of intimacy, but servitude.

Her first full shift in Nathan’s home is marked by total control. He takes her purse and phone, strips her, cages her, and controls every moment of her existence.

There is no physical violence at first, but the psychological toll is enormous. The rhythm of obedience and reward—his “Good girl”—becomes the anchor of her existence.

Eventually, Nathan declares the eight-hour agreement null, stating that he intends to “keep” her. Gia submits without protest, retreating into routine, which slowly solidifies into a new identity.

As time passes, Nathan’s control deepens. He removes all markers of time and isolates her further.

Her voice, once articulate and questioning, is reduced to barking and gestures. Her body is punished for small infractions.

When she meets Cupcake, another woman who has long since been broken by the same system, Gia glimpses her likely future. Cupcake is mute, submissive, and quickly disappears, presumably discarded.

The threat of disposability haunts every moment.

Gia briefly attempts escape but fails. Nathan catches her and punishes her with starvation and silence.

Her resistance crumbles. She eats dog food, accepts tasering, and eventually gives up all pretense of autonomy.

Nathan moves her to the “Pink Room,” a grotesque, childlike prison filled with lace, stuffed animals, and surveillance cameras. There, she is renamed “Shy Girl.

” Her humanity erodes further as the outside world fades away. Kennedy’s efforts to find her are mocked by Nathan, who shows her a missing person flyer.

Gia’s voice is gone; only whispers remain.

Years pass. She loses all sense of time and begins to physically transform—fur, claws, teeth.

This metamorphosis is a symbolic manifestation of the identity Nathan imposed, but it takes on a life of its own. Gia’s transformation into an animal is no longer for his pleasure but a terrifying act of resistance.

She becomes the dog he wanted, but in a way he cannot control. The pregnancy resulting from his assaults ends in her self-induced abortion and consumption of the malformed fetus—a horrifying assertion of bodily autonomy.

Nathan, disturbed by her new form, offers her freedom. He provides her with money and her old belongings, including blackmail photos.

But Gia no longer recognizes these things as meaningful. She mauls and kills Nathan in a brutal, feral act of revenge.

His fantasy destroyed, she devours him and escapes.

Outside, she meets Cupcake again, who reveals she was complicit, emotionally tethered to Nathan, and has been captive for over a decade. Cupcake gives Gia a ten-minute head start rather than stop her.

Gia takes it.

The final scenes show her escaping into the wild. She crashes a car, shrugs it off, and runs.

Her transformation is complete. She is no longer Gia, or Shy Girl, or anyone who can be reclaimed.

She is something new—free, terrifying, and irrevocably changed.

Shy Girl ends not with rescue, but rupture. Freedom does not return Gia to who she was; it births someone entirely different.

What she gains is not healing, but release. The novel leaves readers not with closure, but with the echo of a woman who refused to be shaped any longer by someone else’s design—even if it meant becoming something inhuman.

Characters

Gia / Shy Girl

Gia, later renamed “Shy Girl,” is the emotional and psychological nucleus of Shy Girl by Mia Ballard. Her character journey unfolds through an arc of economic desperation, psychological unraveling, and profound transformation—first into a submissive object of control and eventually into a creature of vengeance.

At the start, Gia is introduced as a woman teetering on the edge of survival: intelligent, regimented, and deeply repressed. Her career in accounting and her obsession with control manifest in daily rituals—counting blueberries, rehearsing emotions, compartmentalizing grief.

This precision is a shield against a lifetime of abandonment and poverty, stemming from a mother who left and a father who checked out emotionally. The sudden loss of her job breaks that carefully maintained balance, forcing her into the world of sugar dating not out of desire but out of raw necessity.

Gia’s descent into her submissive role is both calculated and tragic. When she meets Nathan through SDForMe.

com, her fear and financial panic override her instincts. Her transformation is initially framed as a pragmatic decision—an exchange of time for money—but quickly turns into an erosion of agency.

As Nathan’s control intensifies, Gia slips into the persona of “Shy Girl,” an identity stripped of humanity. The obedience, crawling, and barking begin as performances but soon become instinctive, highlighting how survival mechanisms can become self-erasing.

What is especially haunting is Gia’s complicity in her own dehumanization; she rationalizes, trains herself, and even begins to embrace the structure. Her inner monologue doesn’t protest—she clings to routine, to Nathan’s approval, to the “good girl” affirmations as if they are the only life raft in a sea of disorientation.

And yet, Gia is not a passive victim. Her endurance and adaptability are testaments to a buried resilience.

When Nathan escalates from psychological manipulation to complete imprisonment, Gia experiences a surreal transformation—her body growing fur, claws, and fangs, a grotesque physical metaphor for the psychological beast she has become. This metamorphosis is not just survival—it is rebellion.

By the novel’s end, Gia rejects victimhood, devours Nathan, and disappears into the wilderness, more feral than human. She doesn’t reclaim her former self but births a new identity forged in pain, violence, and a primal hunger for freedom.

Her journey is less about redemption and more about reclamation—of her body, her will, and the narrative of her own existence.

Nathan

Nathan is the chilling architect of Gia’s descent—a figure cloaked in gentleness, rationality, and control. From his introduction, he positions himself as a benefactor, offering financial salvation in exchange for vague companionship.

He is polite, clean, articulate—a man who masks coercion in civility. This duplicity is Nathan’s most terrifying trait: he never yells, rarely raises a hand, but exerts omnipresent power.

His insistence that their arrangement is “real” blurs boundaries, luring Gia deeper into a dynamic that is entirely on his terms. Nathan’s home is staged like a showroom, devoid of intimacy, much like his emotions.

He commands obedience not through brute force, initially, but through structure—rules, praise, punishments—a grooming tactic that turns Gia into a dependent, eager for validation.

As the relationship progresses, Nathan becomes increasingly sadistic. He removes Gia’s agency piece by piece, beginning with the symbolic stripping of her name and autonomy.

He orchestrates her captivity with eerie precision, introducing cages, collars, and infantilized rooms to reinforce domination. What makes Nathan so disturbing is his unflinching detachment: he tortures Gia emotionally and physically while maintaining an affect of calm, never overtly enraged but always in control.

His surveillance of Gia, his manipulative punishments (like tooth extraction or starvation), and his use of live broadcasting for sexual acts reveal a profound need for power and validation through complete subjugation.

Nathan’s unraveling occurs not through confrontation but through the collapse of his own fantasy. When Gia’s body begins to physically transform, he recoils—not because she’s dangerous, but because he loses control over her.

Her becoming is his undoing. In the final scenes, he attempts to reassert dominance by offering money and blackmail, but by then, the power dynamic has inverted.

Nathan’s death at Gia’s hands—ripped apart and devoured—is the narrative’s brutal justice. He is a predator undone by the monster he thought he created, unaware she had been evolving all along.

Kennedy

Kennedy, Gia’s best friend, serves as the emotional and narrative contrast to the protagonist’s unraveling. She represents a version of conventional success and domestic stability: a suburban mother, socially adept, full of warmth and judgment-free support.

Kennedy’s presence in Shy Girl offers a glimpse of what Gia’s life might have looked like in another timeline—if she had a more secure upbringing, more emotional safety, more choices. Her reactions to Gia’s confessions are strikingly nonjudgmental, but also naively optimistic.

She listens, reassures, and tries to maintain normalcy, but remains unaware of the extent of Gia’s suffering.

Kennedy is not a savior but a symbol—of a world that Gia cannot return to. Even when she searches for Gia after her disappearance, her concern exists within the limits of a world that still plays by rational rules.

She cannot imagine the magnitude of Gia’s captivity or transformation. In Gia’s imagination, Kennedy becomes a ghost—someone to whom she whispers apologies, someone who reminds her of who she used to be.

Kennedy’s failure to rescue Gia isn’t an act of neglect but of powerlessness; the systems and expectations she represents are insufficient in the face of the extremity of Gia’s reality. Yet her continued existence offers a subtle emotional tether to humanity, reminding Gia—and the reader—that there was once a version of life before the cage.

Cupcake

Cupcake is perhaps the most tragic and eerie figure in the novel. Introduced first as another captive—bruised, silent, submissive—she seems at first to be a harrowing glimpse of Gia’s possible future.

Cupcake is the “good dog,” a girl who has long since stopped resisting, who moves with the mechanical obedience of someone who’s forgotten freedom. Her presence heightens the horror of Gia’s situation, acting as a ghostly mirror of what awaits.

But later, in a shocking twist, Cupcake returns—not as a victim, but as a willing participant. Her deep psychological entanglement with Nathan reveals that she has stayed with him out of twisted love, loyalty, or perhaps dependency so ingrained it feels like love.

Her revelation adds emotional complexity to the narrative’s moral center. Cupcake mourns Nathan, defends him, and even facilitates his control over Gia.

She is both betrayer and fellow prisoner. Her complicity is not born of malice but of years of psychological grooming and brokenness.

When Gia finally escapes and exacts her vengeance, Cupcake does not stop her. Instead, she gives her ten minutes to flee—an ambiguous gesture that is both enabling and elegiac.

In this moment, Cupcake is neither antagonist nor ally, but a tragic figure who chose captivity when freedom seemed more frightening. Her presence lingers as a cautionary tale: not all cages have visible bars, and not all prisoners seek escape.

Themes

Submission as a Survival Strategy

Gia’s transformation into “Shy Girl” is not the result of a singular decision but the accumulation of countless calculated compromises, each made in the interest of surviving economic instability, social alienation, and deep psychological wounds. Her decision to enter into a sugar dating arrangement, and later to accept the humiliating role of a submissive pet, begins as a transaction—one rooted in the urgent need to pay rent, escape joblessness, and recover a semblance of control.

But what unfolds is not simply a story of financial dependence; it is a chronicle of how submission becomes a means of enduring a world that has repeatedly denied her dignity. Rather than romanticize or eroticize the dynamic, Shy Girl frames submission as a pragmatic response to desperation.

Gia does not dream of obedience—she performs it out of necessity. Initially, she regulates her emotions, routines, and interactions with meticulous control to prevent chaos.

When that fails, she turns to another form of control—externalized and imposed by Nathan, but still understood as structure. Her acceptance of commands, punishments, and roles is not driven by fetish but by the numb pragmatism of someone who has already lost everything.

The progression from financial agreement to permanent imprisonment is not marked by dramatic resistance but by a dull surrender that feels logical, even inevitable. This reveals a disturbing reality: when the world offers no viable choices, submission may masquerade as agency.

The tragedy is not that Gia chooses this path, but that she believes it is the only one available.

Erasure of Identity Through Psychological Control

Gia’s erasure is both literal and symbolic. From the moment Nathan renames her “Shy Girl,” he initiates a comprehensive dismantling of her identity, targeting not just her body, but her language, memory, and sense of time.

Names, objects, routines—all once essential to her carefully constructed world—are stripped away. She is no longer allowed to speak freely, to use her phone, or to retain personal belongings.

This eradication of personal signifiers is central to Nathan’s methodology of control. His power lies not in overt violence alone but in the systematic breakdown of the boundaries that define Gia’s humanity.

She begins as a woman struggling to hold herself together through routines and rituals, but over time, those routines are replaced by ones designed by Nathan: barking, crawling, wagging, waiting for commands. These acts, repeated daily, replace independent thought with behavioral conditioning.

The Pink Room, with its pastel colors and infantilized decor, completes this regression. Gia is not just imprisoned physically; she is psychologically reverted to a state of dependency so complete that her internal voice is drowned out.

Even her memories begin to fade, replaced by imagined conversations and apologies whispered to absent people. The final transformation into a dog-like creature—complete with fur, claws, and sharpened teeth—underscores the extent to which identity, when methodically denied, will eventually mutate into something unrecognizable.

What remains is not the woman who once loved numbers and blueberry oatmeal, but a shell built from obedience, silence, and survival.

Commodification of the Female Body

Gia’s journey illustrates how the female body is treated as both product and performance—purchased, evaluated, and ultimately disposed of. Her initial encounter with sugar dating already positions her body as a currency, but Shy Girl does not stop at economic exploitation.

The novel tracks how commodification evolves into spectacle. Nathan’s voyeuristic impulses—filming their encounters, broadcasting her abuse, critiquing her obedience—reveal that Gia is not merely owned; she is exhibited.

Her value is based on her ability to conform to a role, to entertain, to behave. When a new woman enters the picture and fails to meet these standards, Nathan’s dissatisfaction reveals the transactional logic underlying their dynamic: even among captives, there is competition and comparison.

The female body becomes a site of consumption and performance, with standards of perfection applied regardless of consent. This objectification is not confined to Nathan alone.

The men on SDForMe. com, the people in Gino’s, even society at large participate in the commodification that brought Gia to Nathan’s door in the first place.

Her descent into pethood is not an anomaly but a metaphor for the social reality many women experience—judged not on their personhood, but on how well they play the part expected of them. The grotesque final act, in which Gia devours Nathan, functions as both vengeance and reversal.

She reclaims her body—not as object, but as weapon—and in doing so, flips the gaze back onto her abuser, refusing to be consumed any longer.

Isolation and the Collapse of Human Connection

Throughout Shy Girl, isolation is as much a weapon as the collar or the cage. Gia begins her journey already estranged from the world: a childhood marked by abandonment, an adulthood of financial instability, and friendships that exist more in theory than in practice.

Her connection to Kennedy, while comforting at times, is unable to bridge the chasm of Gia’s internal suffering. As her entanglement with Nathan deepens, all remaining links to the outside world are severed.

He strips her of communication tools, eliminates time markers, and limits her social contact. The introduction of Cupcake, another broken captive, does not provide solace but reinforces her solitude.

Cupcake’s silence and complicity underline that even among others, Gia is alone in her suffering. When Kennedy’s search efforts appear briefly through a missing person flyer, Nathan uses it not as a sign of hope but as psychological leverage, taunting Gia with the illusion that no one truly cares.

Over time, this erosion of human connection begins to warp Gia’s inner life. She imagines conversations, speaks to herself in apology, and begins to inhabit a mental world where isolation is not just a condition but an identity.

The final chapters make clear that her transformation is shaped not only by abuse but by loneliness so profound it redefines her understanding of reality. Even her escape at the end is not a return to people or community, but a flight into the wild—her last remaining refuge from a human world that failed to protect her.

Reclamation of Power Through Transformation

The arc of Gia’s metamorphosis—from Gia to Shy Girl to a beast-like entity—complicates traditional narratives of trauma and survival. Her transformation is not clean or redemptive.

It is grotesque, primal, and horrifying, but it is hers. For most of the narrative, power belongs to Nathan: he commands, punishes, names, and rewrites reality.

But as Gia’s body begins to mutate—sprouting fur, sharpening teeth—she becomes something ungovernable. What was once a fantasy for Nathan becomes a nightmare he cannot control.

Her final acts, including aborting a pregnancy through violent self-harm and ultimately killing and consuming Nathan, mark a reclaiming of autonomy through destruction. She no longer seeks approval, money, or even freedom in the conventional sense.

Her agency is expressed through annihilation. By embodying the very image of the “dog” Nathan constructed, she distorts it into something that terrifies him.

Her final escape is not a return to humanity, but a liberation from it. She abandons language, identity, money, and even logic in favor of instinct, rage, and self-direction.

This reclamation is radical in its rejection of societal norms. Rather than seek healing, Gia becomes a new creature entirely—one unbound by the systems that caged her.

Shy Girl proposes that sometimes, survival does not mean returning to who one was before trauma, but becoming someone—or something—entirely different. In Gia’s case, that evolution is monstrous, but it is hers alone.

It is the first and only decision in the narrative she makes without fear, apology, or submission.