Sunrise on the Reaping Summary, Characters and Themes

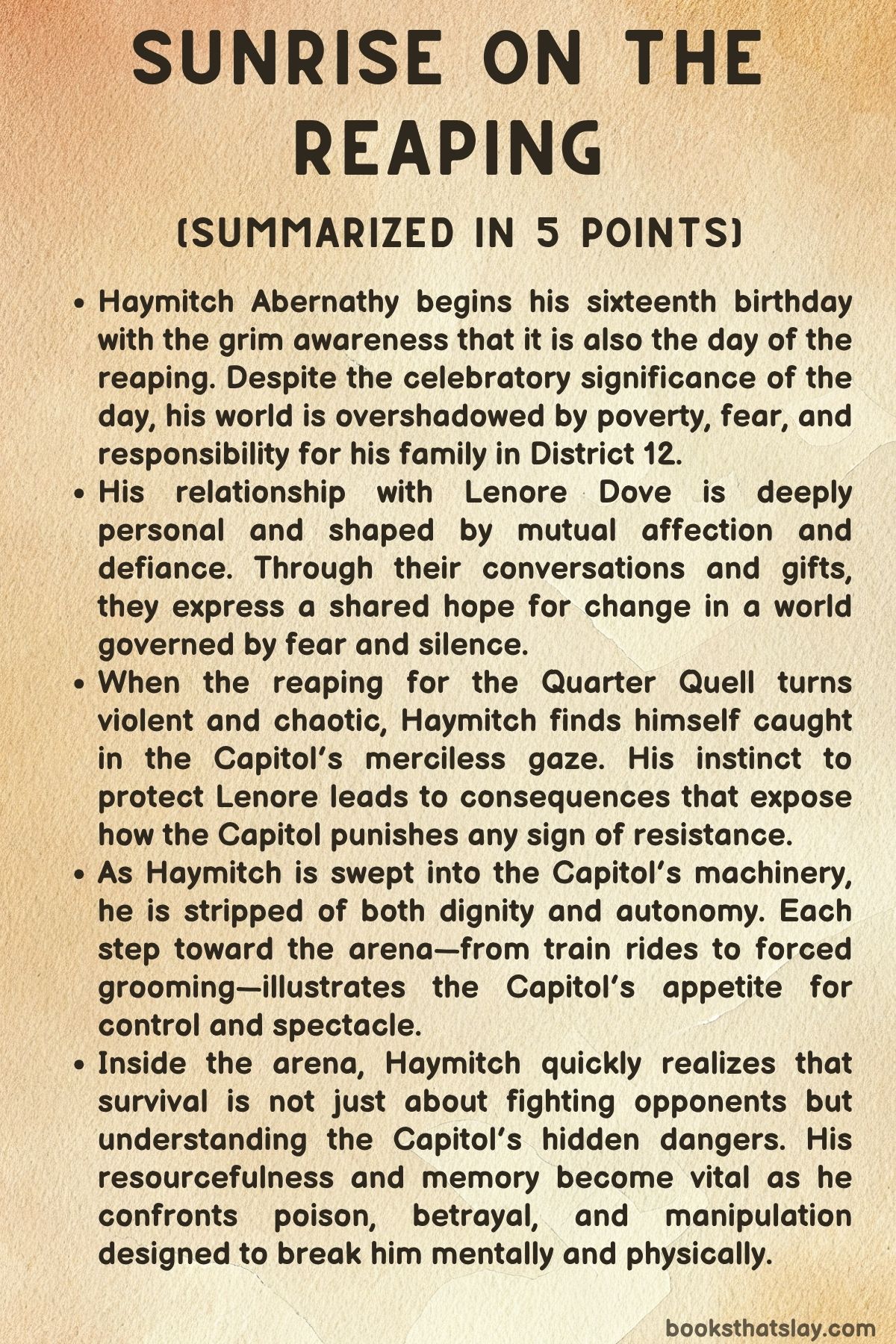

Sunrise on the Reaping by Suzanne Collins returns to the brutal world of Panem through the eyes of Haymitch Abernathy, the sardonic mentor known from the original Hunger Games trilogy. This narrative offers an unflinching, emotionally raw account of Haymitch’s teenage years, his experience in the 50th Hunger Games, and the aftermath that shapes his future.

Set against the backdrop of the Quarter Quell, the story explores the psychological scars of surviving institutional violence and the toll it exacts on love, hope, and identity. Collins focuses on Haymitch’s inner life, making him not only a survivor but a reluctant symbol of resistance and loss.

Summary

On the morning of his sixteenth birthday, Haymitch Abernathy wakes up in District 12 with a sense of dread. The reaping is hours away, and though it’s supposed to be a day of personal celebration, the grim shadow of the Hunger Games looms over everything.

Haymitch lives in the Seam with his widowed mother and younger brother Sid, both of whom rely on his ingenuity and resilience. He earns a living by brewing moonshine in the woods with a woman named Hattie Meeney.

Despite the illegality of the job, it’s preferable to catching rats, and the income helps keep his family afloat. Hattie gives him a birthday gift—an unspoken sign of affection and respect—which represents the close-knit, barter-driven community of District 12.

Haymitch’s life is marked by both quiet responsibility and stolen moments of freedom, particularly with Lenore Dove, a girl from the Covey. Lenore is passionate, musically gifted, and politically aware.

Her songs, often banned by the Capitol, push Haymitch to consider a world beyond fear and obedience. She gives him a flint striker, a simple gift that represents survival and rebellion.

Their relationship is filled with quiet moments of joy and discussion, yet always tinged with the knowledge that the Capitol controls every aspect of their lives.

At the reaping, things spiral rapidly. The second Quarter Quell requires double the tributes, and after the names of Maysilee Donner and Louella McCoy are called, a tribute named Woodbine Chance attempts to flee.

He is executed on the spot. As the chaos unfolds, Haymitch tries to protect Lenore from a Peacekeeper’s assault.

This act of defiance leads to a Capitol escort, Drusilla Sickle, choosing him as a replacement tribute. His selection is not a matter of chance but punishment for stepping out of line.

The crowd’s horror, the Capitol’s delayed broadcast, and the abrupt imposition of order all highlight the powerlessness of the districts and the performative cruelty of the Capitol.

Instead of the customary farewells at the Justice Building, the Capitol stages a tightly managed set of “goodbyes” to harvest emotion for the cameras. Plutarch Heavensbee intervenes to allow Haymitch a staged moment with his family, during which Haymitch gives Sid his possessions and charges him with caring for their mother.

Haymitch tries to leave Sid with a sense of strength, though the underlying despair is unmissable.

On the train to the Capitol, Haymitch is restrained, electrocuted, and silenced. The most heartbreaking image remains etched in his mind: Lenore on a distant ridge, holding the gumdrops he gave her, drenched in rain.

It’s a moment the Capitol doesn’t catch, but it becomes one of the most profound memories of his life. As the train speeds toward the Capitol, Haymitch is consumed by a storm of emotions—rage, guilt, fear, and helplessness.

He reflects on the dreams he once had: a life with Lenore, a better future for Sid, escape from poverty. Now, those dreams seem impossible.

Onboard, he reconnects with Louella, who quickly becomes a trusted ally. They share history and humor, a fragile balm against the horrors to come.

Haymitch distrusts Maysilee and finds Wyatt difficult to read. As the Capitol begins its preparation for the Games, the tributes are subjected to grooming, psychological manipulation, and surveillance.

Even small kindnesses, like a birthday cupcake, come with an agenda. Plutarch seems warmer than others, but Haymitch knows every gesture is calculated.

Louella’s erratic behavior and her knowledge of a District 11 harvest song hint at Capitol interference—possibly abduction or brainwashing. As Haymitch prepares to enter the arena, the weight of history and horror presses down on him.

Mags, a past victor, offers the only real kindness, acknowledging that not all of them will return and offering a sliver of comfort.

The arena appears tranquil—a trap disguised as beauty. Haymitch escapes the bloodbath and finds a pack of limited supplies.

Poisoned water nearly kills him until he remembers an old remedy involving charcoal, a lesson from his grandmother. This becomes a key insight: everything in the arena, no matter how innocuous, is a weapon.

His survival becomes increasingly dependent on intelligence, memory, and luck.

Haymitch grieves Wyatt’s death, which he believes was an act of protection for Louella. Louella finds him again, but she’s clearly being manipulated.

He cares for her, despite her unstable behavior, and tries to protect her. Her death—triggered by contact with a poisonous plant—devastates him.

Her body reacts violently, and Haymitch, in a moment of rage and resistance, rips out her Capitol-embedded tracker. This act is one of open defiance, and the Gamemakers retaliate immediately.

They send in muttation butterflies with electric stings. Haymitch survives by using a gas plant to ignite an explosion, killing the mutts.

He discovers their hidden tunnel entry, confirming a weakness in the arena’s design. That night, he camps in a tree and watches Louella’s face projected in the sky, a tragic memorial.

A sponsor sends him food and drink, temporarily lifting his spirits. He eats alone, now fully aware that survival will come through cunning and adaptability.

Ampert, a fellow tribute, appears and shares information: Maysilee is alive, a mountain battle is unfolding, and the Newcomers are dying. Haymitch and Ampert form a secret alliance, disguised as student and guide.

Haymitch provides knowledge on poisons and mutts, readying for an arena sabotage: a plan to flood the system.

The narrative then shifts to the aftermath. Haymitch wins the Games but returns home to devastation.

The Capitol has murdered Lenore using poisoned gumdrops, and Haymitch is left shattered. The loss of Lenore is the final blow.

She dies in his arms, and he blames himself for breaking his promise to keep her safe. President Snow uses her death to punish Haymitch for mocking the Capitol during the Games.

He retreats into isolation and alcoholism. Weekly food and money deliveries from the Capitol are cruel reminders that they still own him.

Haunted by dreams and guilt, he can’t escape Lenore’s memory. Her absence becomes a ghost he cannot exorcise.

Her love was once his reason to hope, and now it’s a wound he can’t close.

Even as the Capitol attempts to keep him emotionally broken, her final message—“You promised me”—forces him to survive. He begins to recognize signs of rebellion in graffiti and underground resistance.

Plutarch approaches him, suggesting Haymitch still has a role to play. Though emotionally numb and physically ruined, Haymitch chooses to live, not for himself, but because Lenore’s memory won’t allow him to surrender completely.

As years pass, he becomes a mentor, finding fragments of himself in tributes like Katniss and Peeta. Lenore never leaves him.

In dreams, she ages as he does, always loving him, always waiting. She is the last remnant of who he once was, and through her, he endures—damaged, unwilling, but alive.

Characters

Haymitch Abernathy

Haymitch is at the heart of Sunrise on the Reaping, a character rendered in complex emotional layers that evolve through trauma, love, and resistance. At sixteen, Haymitch begins as a boy burdened by poverty and familial responsibility, but he displays quiet resilience and practical intelligence.

His work making moonshine, while illicit, is emblematic of his ingenuity and the economic improvisation required to survive in District 12. What separates Haymitch from many of his peers is his capacity for emotional depth, particularly in his love for Lenore Dove.

This relationship is a touchstone for his humanity and emerging political consciousness. Lenore challenges him to think beyond fatalism, to hope, and ultimately to resist.

When Haymitch is thrust into the 50th Hunger Games, his transformation begins in earnest. His strategic thinking and moral compass guide him, even amid horror, suggesting a mind that works not only to survive but to preserve dignity.

Post-victory, Haymitch’s descent into alcoholism and emotional collapse reflects the cost of defying the Capitol. The loss of Lenore — assassinated by Snow through poisoned gumdrops — becomes his crucifixion.

He never recovers, not entirely. Yet, even as he spirals, Haymitch clings to the ideals she embodied.

Haunted by memory, he becomes a reluctant revolutionary, his pain reframed as fuel for rebellion. His eventual bond with Katniss and Peeta shows a man still capable of love and mentorship, even while hollowed out.

In essence, Haymitch is a survivor not merely of the Games, but of the Capitol’s ongoing campaign to destroy the soul of its people.

Lenore Dove

Lenore Dove emerges as the emotional and moral center of Sunrise on the Reaping, even though her physical presence is limited. A daughter of the Covey, Lenore is portrayed as both artist and rebel.

Her music is not simply aesthetic; it is revolutionary. She sings forbidden songs with an unshakable awareness of their political resonance.

Her love for Haymitch is both intimate and philosophical, filled with whispered debates about fate, freedom, and survival. The flint striker she gifts him functions as a symbol of resistance — a token of hope meant to ignite not just fire, but belief in a future beyond the Capitol’s reach.

Lenore’s tragic death at the hands of Snow — murdered through a calculated poisoning — underscores her importance. She is not collateral damage but a target, eliminated to break Haymitch’s spirit.

Her final message, scrawled in rebel graffiti, suggests she remains a guiding force from beyond the grave. Lenore is more than a love interest; she represents the dream of a different world.

Her presence haunts the narrative as a ghost of what could have been, and her influence shapes Haymitch’s enduring hatred for the Capitol and eventual quiet acts of defiance.

Sid Abernathy

Sid, Haymitch’s younger brother, serves as a poignant representation of innocence lost in the harsh reality of Panem. Throughout Sunrise on the Reaping, Sid is portrayed as vulnerable but eager, watching his brother for cues on how to navigate a brutal world.

During Haymitch’s forced farewell, Sid becomes the recipient of a symbolic passing of the torch. Haymitch gives him gumdrops, peanuts, and a command to be strong — all small gestures infused with heartbreaking weight.

Sid is emotionally shattered by Haymitch’s reaping, but he channels that grief into a moment of performance for the Capitol cameras, forced into composure by the cruelty of propaganda. This coerced farewell represents the emotional mutilation Panem demands of its citizens.

While the narrative does not follow Sid’s arc post-reaping, his image remains a beacon for Haymitch — a reason to continue resisting, to survive, to one day fulfill his promise of ending the cycle of violence. Sid, like Lenore, becomes a part of Haymitch’s internal moral compass, a voice reminding him of love, duty, and the unbearable stakes of surrender.

Drusilla Sickle

Drusilla Sickle is the grotesque face of Capitol cruelty in Sunrise on the Reaping, embodying the perverse theatricality that governs Panem. She is the Capitol escort assigned to District 12, and her every word and gesture seem surgically engineered to dehumanize.

Her tone-deaf enthusiasm, exaggerated outfits, and vapid commentary serve as satire of media complicity in tyranny. Drusilla is not merely annoying — she is dangerous.

She weaponizes the reaping process by choosing Haymitch in a moment that blends vengeance, spectacle, and arbitrary punishment. Her decision to cancel the Justice Building farewells robs families of closure, a strategic cruelty masked as crowd control.

Her role later in the train and Capitol preparations, including her unhinged attack on Maysilee, further reveals her instability and venomous nature. Yet, she is tolerated and even celebrated in the Capitol — a sign of how deeply ingrained cruelty has become in their social fabric.

Drusilla functions not just as a villain but as a symbol of systemic rot, where violence is normalized and empathy is absent.

Louella McCoy (Lou Lou)

Louella McCoy, affectionately called Lou Lou, is a heartbreaking portrait of innocence shattered and repurposed by the Capitol’s machinery in Sunrise on the Reaping. Initially introduced as a younger tribute from District 12, Louella’s early bond with Haymitch hints at shared history and affection.

However, her behavior quickly reveals signs of trauma, manipulation, or even mind control — she hums songs from District 11 despite being from 12, and her detached demeanor suggests Capitol interference. Her tragic arc culminates when she consumes a poisonous flower, and her death is a moment of unfiltered anguish for Haymitch.

He is both protector and mourner, holding her as she convulses and dies, unable to prevent the inevitable. Her implanted tracker, which Haymitch later destroys in a moment of rebellion, becomes symbolic — she was not a child anymore but a tool in the Capitol’s sick narrative.

Lou Lou’s death radicalizes Haymitch further and marks one of the clearest emotional ruptures in his Games experience. Her image, projected into the sky post-mortem, is both memorial and manipulation.

Maysilee Donner

Maysilee is initially portrayed through Haymitch’s judgmental lens — as self-important and out of touch. However, her character undergoes a striking transformation as Sunrise on the Reaping unfolds.

Her strength, intellect, and moral clarity become undeniable. When Drusilla attacks her and she fights back, it becomes a defining moment: she refuses to be dehumanized.

Maysilee is courageous and principled, and although her initial friction with Haymitch suggests incompatibility, they are more alike than he admits. She, too, believes in making the Games about more than just death — a chance to challenge the system, even in small ways.

By the time she reenters the narrative through Ampert’s updates, her absence is felt as a strategic loss, reinforcing her value in the alliance. Maysilee, like Lenore, represents a kind of feminine resistance that is deeply intellectual, compassionate, and quietly revolutionary.

Plutarch Heavensbee

Plutarch Heavensbee is a master manipulator and enigmatic figure whose role in Sunrise on the Reaping complicates the idea of allyship. He is part of the Capitol elite but also a secret rebel, walking the razor’s edge between complicity and subversion.

His interactions with Haymitch are layered with duplicity: he negotiates with Snow to secure farewells but spins them for emotional capital; he offers kindness but always through a strategic lens. His interest in Haymitch is less about friendship and more about utility — seeing in him the spark of defiance necessary for rebellion.

Later, as Haymitch spirals, Plutarch reappears to recruit him into the resistance. His pitch is manipulative but not wrong: Haymitch, shaped by grief and fury, is a perfect candidate for subversive warfare.

Plutarch is less a character of warmth and more a symbol of moral grayness — willing to use pain as a weapon for revolution, and justified in doing so.

President Snow

Though he does not appear directly in much of Sunrise on the Reaping, President Snow’s influence looms over every decision, punishment, and act of violence. He is the architect of terror, the orchestrator of Lenore’s assassination, and the grand manipulator behind the Games’ sadism.

His cruelty is precise and personalized — he doesn’t just kill people; he kills what they represent. Lenore is eliminated not as a rebel, but as a symbol of Haymitch’s hope.

Snow’s style of tyranny is surgical: he allows Haymitch to live, sending money and food as constant reminders of his power. Every act of “generosity” from Snow is a leash, not a gift.

He is both omnipotent and petty, using state violence to enforce emotional ruin. In Haymitch’s psyche, Snow becomes a mythic force, the embodiment of every nightmare and loss.

Ampert

Ampert is a secondary but vital character in Sunrise on the Reaping, embodying quiet strength and pragmatic courage. His reentry into Haymitch’s narrative during the Games serves as a moment of reunion and cooperation.

He is the voice of information, confirming deaths, strategies, and opportunities. Ampert’s plan to work together covertly, sharing knowledge rather than direct alliance, is a testament to the evolving nature of resistance.

His presence restores Haymitch’s sense of purpose, and the sunflower tokens he carries add a bittersweet touch, connecting the fallen with the living. Ampert is a stabilizing force, not defined by grand gestures but by his clarity, empathy, and willingness to adapt.

His role, though limited in page time, represents the possibility of solidarity and intelligence amid chaos.

Themes

State Violence and Systemic Oppression

The world of Sunrise on the Reaping is defined by an unrelenting structure of state-sanctioned brutality, where the Capitol’s authority is maintained through spectacle, punishment, and manipulation. The Hunger Games are not merely a tool of entertainment, but a deliberate mechanism of terror.

The reaping day, marked by its grim rituals and forced cheer, strips individuals of their agency. Haymitch’s journey begins with this spectacle, as his sixteenth birthday becomes inseparable from the state’s annual cruelty.

What could be a day of personal celebration is instead swallowed by dread and surveillance. The public execution of Woodbine Chance serves as a horrifying display of control, meant to quell resistance and demonstrate the absolute reach of Capitol power.

The manipulation continues when the Capitol denies Haymitch a chance to say goodbye to his family and then weaponizes their grief for propaganda. This duality—punishing emotion while harvesting it—captures how Panem’s regime co-opts humanity itself.

The Peacekeepers, stylists, and handlers each play their part in reducing tributes to symbols rather than people. Even “kindness” becomes a tool of coercion, making it clear that under such a regime, nothing is given without an ulterior motive.

The Capitol’s control is not limited to physical domination but extends into psychological erosion, leaving tributes broken before they ever enter the arena.

Personal Love as Resistance

The relationship between Haymitch and Lenore Dove stands in sharp contrast to the cruelty around them. Their bond is not only rooted in affection but also in shared intellect and values.

Lenore is not just a romantic figure; she challenges Haymitch’s acceptance of the world’s fatalism, offering him an alternate vision—one where individual choice and symbolic acts matter. Her songs, her gift of the flint striker, and her insistence on hope represent subtle acts of resistance.

Their stolen moments in the Meadow are defiant in their simplicity; in a world where even time and space are governed by fear, their choice to love, debate, and dream freely becomes revolutionary. When Haymitch protects her during the reaping chaos, he steps directly into the Capitol’s crosshairs.

This act of love—fueled by instinct and courage—seals his fate. After Lenore’s death, her influence remains, pushing Haymitch to confront his own despair.

Her message, “You promised me,” acts as a tether to meaning and purpose, pulling him from the brink of emotional obliteration. Love, in this context, becomes more than personal comfort—it is memory, motivation, and the seed of rebellion.

Even in death, Lenore’s presence forces Haymitch to endure and act, proving that true love in an oppressive world is not just a solace—it is a quiet refusal to submit.

Grief and Endurance

Haymitch’s character is built around sustained loss, and Sunrise on the Reaping tracks the long arc of his grieving process. From the moment he is taken from District 12, every relationship he treasures is stripped away.

The deaths of Wyatt, Lou Lou, and especially Lenore push him into emotional freefall. The Capitol ensures that his grief is not just a byproduct of war, but a punishment designed to fracture his spirit.

President Snow’s calculated decision to murder Lenore through poisoned gumdrops is not merely an act of revenge—it is a psychological assassination. In the aftermath, Haymitch turns to alcohol and isolation, his mind haunted by memories that refuse to fade.

Quotations from “The Raven” mark his descent into obsessive mourning, with “Nevermore” echoing through his failed attempts to forget, forgive, or move on. Yet grief also becomes a crucible.

It hardens Haymitch but also preserves his core humanity. Despite the Capitol’s attempts to erase meaning from his life, the memory of love, of lost friendships, and of broken promises keep him tethered to the world.

Even his eventual mentorship of Katniss and Peeta reflects this endurance. His grief never disappears, but it becomes part of his identity—informing his bitterness, but also his refusal to be fully consumed by it.

The Illusion of Choice and the Mechanics of Control

Choice is a carefully curated illusion in Panem, and Sunrise on the Reaping illustrates this theme with devastating clarity. Haymitch’s so-called selection during the reaping is not by random lottery, but the result of his defiance and the Capitol’s desire to make an example of him.

Every action thereafter—from his grooming to his forced sponsorship displays—is manipulated. Even moments that seem spontaneous, like a birthday party on the train, are staged to reinforce the Capitol’s narrative.

Lou Lou’s tragic arc as a reprogrammed or drugged tribute reveals how control extends even into the body and mind, removing autonomy entirely. Haymitch’s refusal to participate in the farce—his rejection of the birthday spectacle, his destruction of Capitol surveillance tools, and his eventual decision to flood the arena—are significant because they reintroduce real choice into a space designed to eliminate it.

By reclaiming control, even briefly, he undermines the Capitol’s entire structure. However, the cost is immense, and the illusion remains dominant.

Even victories are framed within the Capitol’s context, ensuring that rebellion is either hidden or punished. The reader is left with the understanding that autonomy under tyranny is rare, fleeting, and always dangerous—but nonetheless vital.

Memory as Weapon and Refuge

Throughout Haymitch’s journey, memory acts both as a torment and a means of survival. His flashbacks to time with Lenore, his recollection of his grandmother’s advice, and his images of his brother Sid serve as emotional lifelines in moments of despair.

The Capitol understands the power of memory, which is why it seeks to rewrite or manipulate it—editing footage, staging reactions, and crafting false narratives for public consumption. In contrast, Haymitch clings to truth, even when it causes pain.

The loss of Lenore is unbearable, but forgetting her would be a second death, one inflicted by compliance. His dreams, haunted by her presence, evolve from nightmares into moments of clarity.

She ages with him in those dreams, a sign that memory is alive and evolving, not static. This continued connection protects a piece of Haymitch that the Capitol cannot touch.

At the same time, memory becomes a burden. Each new tribute death adds to the weight of remembrance, threatening to drown him.

But without memory, there would be no rebellion, no purpose, no promise to fulfill. In this narrative, remembering becomes a political act.

It asserts humanity in the face of dehumanization, insists on individual truth over state narrative, and preserves the love, pain, and resistance that define Haymitch’s life.