The Antidote Summary, Characters and Themes | Karen Russell

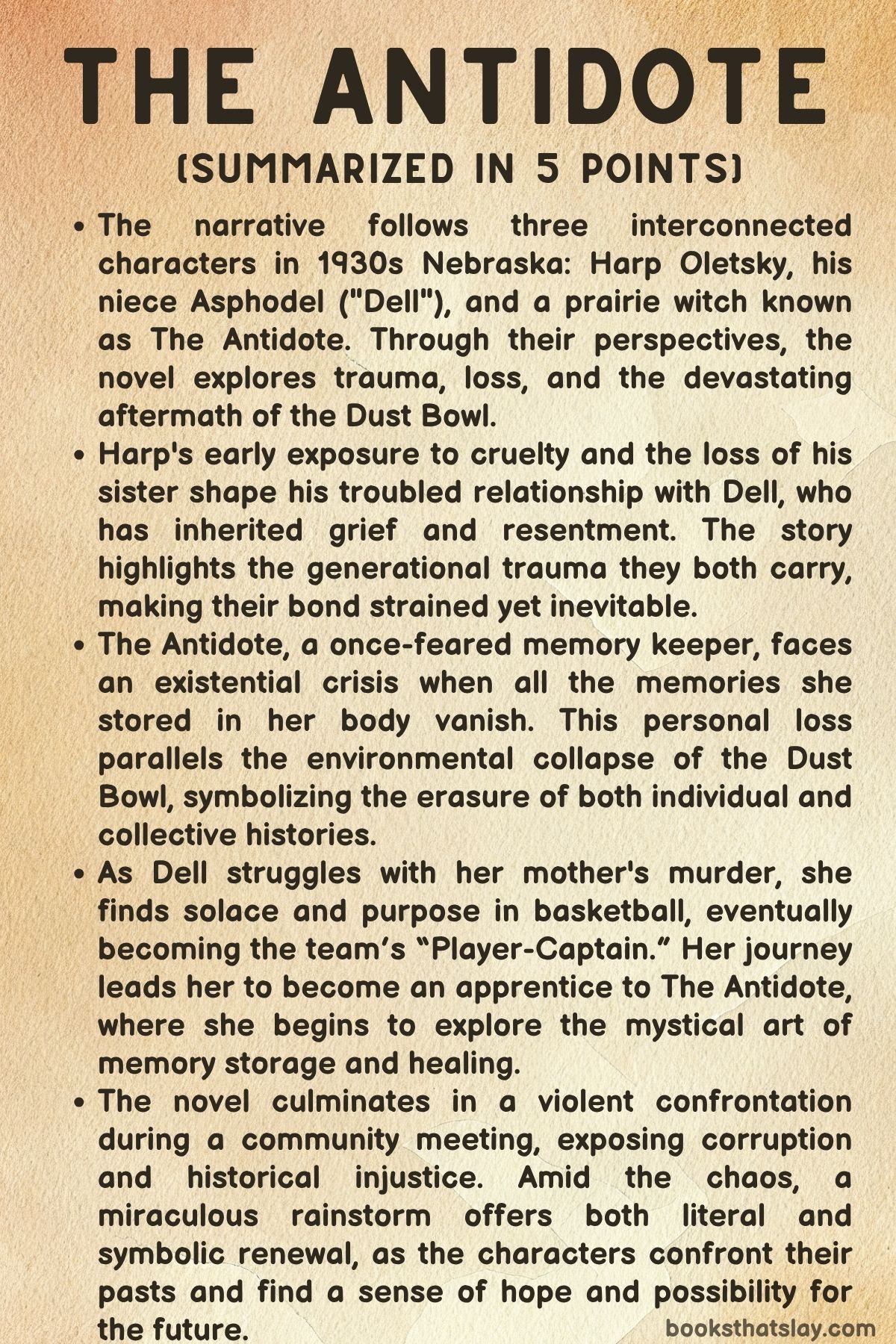

The Antidote by Karen Russell is a dark, lyrical novel set against the haunting backdrop of 1930s Dust Bowl-era Nebraska. Blending historical fiction with speculative elements, it traces the lives of three central characters—Harp Oletsky, his niece Asphodel “Dell,” and a memory-storing prairie witch known as “The Antidote.

” Through these interlaced narratives, the novel explores inherited trauma, the politics of memory, institutional corruption, and the resilience of women and girls in a collapsing world. The land is scorched and the soil is gone, but memories persist—some repressed, some stolen, and some resurrected to tell hard truths. In a time of dust and silence, memory becomes both a weapon and a cure.

Summary

In the small, drought-ravaged town of Uz, Nebraska, three lives—each shaped by loss, guilt, and buried secrets—intersect during the ecological and emotional collapse of the 1930s Dust Bowl. The story begins with Harp Oletsky, who, as a child, witnesses a brutal jackrabbit culling that marks his first encounter with collective violence.

The memory haunts him into adulthood, where he lives as a disillusioned farmer, weighed down by the suicide of his brother, the murder of his sister Lada, and the responsibility of raising her orphaned daughter, Asphodel “Dell” Oletsky.

Dell is a grief-stricken and angry teenager living in Harp’s home, resentful of his inability to recognize her pain and obsessed with the circumstances of her mother’s death. The man convicted of Lada’s murder, Clemson Louis Dew, suffers a botched execution that only deepens Dell’s confusion.

She remembers Dew not as a monster but as a frail, stuttering boy. Eavesdropping on the town’s Party Line, she collects rumors and contradictory accounts that undermine the community’s sanctioned narrative of guilt and justice.

Her growing doubts about Dew’s culpability serve as a broader critique of institutional memory, corruption, and the violent rewriting of truth.

As dust storms loom over the town, another character awakens: a nameless prairie witch known professionally as “The Antidote. ” She once operated as a memory banker, allowing people to deposit painful recollections into her body through a magical earhorn.

But on Black Sunday—April 14, 1935—she wakes in jail to discover that all the memories she stored over the years have vanished. Her personal amnesia mirrors the ecological collapse outside.

She feels hollow, weightless, and spiritually bereft, echoing the townspeople’s existential loss as they wander through a landscape stripped of meaning and sustenance.

The witch’s body was once a vault for truths too heavy to bear, including the memories of victims, criminals, and the morally conflicted. Sheriff Vick Iscoe exploited her talents to erase evidence and manipulate testimony for his own political gain.

His cruelty extends from drowning kittens to fabricating memories to cover up his role in serial murders. He raped the witch under the guise of tenderness, highlighting the disconnect between power and accountability in Uz.

Her silence and endurance, though mistaken for submission, are actually part of a quiet rebellion—one that grows in strength as she reflects on her failures, including her abandonment of a long-lost child taken from her at birth.

Dell, seeking agency and a means to control her inner turmoil, becomes obsessed with basketball and finds community and purpose in her all-girls team, The Dangers. When their coach abandons them, Dell steps up as “Player-Captain,” symbolizing her reluctant emergence as a leader.

To sustain the team, she approaches the witch, requesting to become her apprentice. Initially resistant, the witch recognizes something familiar in Dell—a young Vault, someone capable of housing the collective suffering of others.

Their bond grows, grounded in shared pain and a yearning for transformation.

The narrative deepens with stories from the witch’s past and the lives of other marginalized women. Zintkala Nuni, a Lakota girl stolen from Wounded Knee and raised as a spectacle by white benefactors, becomes a haunting presence in the witch’s memories.

Zintka’s journey through boarding schools, institutions, and repeated betrayals is one of cultural loss, survival, and resistance. She, like many others in the witch’s life, becomes both a moral touchstone and a reminder of the cost of silence.

As the dust storm known as Black Sunday strikes, the community’s social order temporarily collapses. Harp, a reluctant orator, seizes the moment to speak at the local Grange Hall, exposing the Sheriff’s long-hidden crimes.

Using photographic evidence and the witch’s testimony, Harp reveals that the so-called Lucky Rabbit’s Foot Killer was a myth manufactured by the Sheriff to close unsolved cases. The town’s demand for justice quickly turns to confusion and rage.

Harp pushes further, confronting the town with its founding sins—land stolen from the Pawnee and prosperity built on exclusion. His plea for acknowledgment and reparations fractures the crowd’s fragile unity.

The witch, Dell, and other young girls are nearly consumed by the ensuing chaos, as the mob turns on them. But a sudden rainstorm—symbolic of both divine intervention and ecological reprieve—halts the violence.

In the storm’s aftermath, the Sheriff corners the protagonists at the Oletsky farm, where a supernatural encounter involving a scarecrow, a basketball, and a bolt of wind disarms him. He flees, blinded and broken, while Dell and her allies retreat to Harp’s miraculous wheat field.

The novel ends in the refuge of the root cellar. There, the witch, whose name is revealed as Antonina Rossi, communes with the spirit of her deceased son Benjamin.

Through the memory-storing earhorn and the scarecrow’s form, she is flooded with visions of his life and death. Her connection to Dell transforms from mentorship to something more maternal, filling a void in both their lives.

Kittens are born, crops grow, and though the world remains deeply damaged, something like hope flickers through the storm’s residue.

The Antidote closes on a moment of tentative renewal. The characters—Dell, Antonina, Harp, Cleo the photographer—are not healed, but they have confronted the truth.

In doing so, they inherit the burden of remembrance and the possibility of change. The rain does not erase the past; it sanctifies it.

Their survival is not just physical but spiritual, and their shared memory may be the only thing strong enough to rebuild what the dust nearly destroyed.

Characters

Asphodel “Dell” Oletsky

Asphodel “Dell” Oletsky stands at the emotional and symbolic heart of The Antidote, embodying the painful journey from grief to self-determination in a world shattered by ecological collapse and human cruelty. A teenager orphaned by her mother Lada’s murder, Dell grows up haunted by unanswered questions, conflicting narratives, and a suffocating legacy of trauma.

Her home in Uz, Nebraska is both a literal and metaphorical dustbowl—barren, judgmental, and unrelenting. Dell’s relationship with her uncle Harp is fraught, strained by his inability to see her beyond the shadow of her mother, whom he continues to idealize.

Dell carries not just her mother’s death, but also the psychological weight of surviving in a town where violence against women is normalized and memory itself is malleable.

Her obsession with Clemson Louis Dew, the man accused of her mother’s murder, marks Dell’s descent into a labyrinth of moral ambiguity. The details of Dew’s botched execution and his vulnerable demeanor sow doubts in Dell’s mind, disrupting the town’s comfortable villainization of him.

Her hunger for truth, complicated by guilt and empathy, mirrors the novel’s broader interrogation of justice and memory. Simultaneously, Dell’s athletic passion—particularly her leadership of the basketball team, The Dangers—becomes a crucible through which she hones resilience and agency.

Her desire to become the Antidote’s apprentice reveals her longing for control over her own pain and the desire to transmute suffering into something redemptive. Though her first trance is flawed, her resolve and raw power suggest a transition into mystical adulthood, firmly positioning her as both inheritor and breaker of generational cycles.

Harp Oletsky

Harp Oletsky, Dell’s uncle, is a broken man trying to preserve dignity in the wake of personal and national ruin. His memory of the jackrabbit culling—a childhood initiation into communal violence—reverberates throughout his adult life, shaping him into a man both numbed and haunted by brutality.

As a dryland farmer whose life has been decimated by drought, war, and family tragedies, Harp clings to pragmatism, cynicism, and guilt. He mourns his brother Frank, a casualty of World War I and systemic neglect, and his sister Lada, whose death he could neither prevent nor emotionally process.

Yet Harp is not merely a vessel of despair; he is also a reluctant moral compass. His confrontation with the town’s corruption, particularly during his climactic Grange Hall speech, reveals a buried idealism and courage.

The “green miracle” on his farm—the sudden appearance of healthy wheat after Black Sunday—throws Harp into spiritual disarray. Skeptical of divine providence, he nonetheless senses that something sacred and strange has taken root on his land.

This paradox—of a man who disbelieves miracles yet becomes a vessel for one—deepens his character. Ultimately, Harp becomes a catalyst for truth-telling.

His denunciation of Uz’s historical and institutional sins, from land theft to wrongful convictions, ignites both clarity and chaos. He is the embodiment of the novel’s reckoning, a man who speaks truths too painful for his community to hear, and pays the price for it.

Still, Harp’s act of naming injustice allows others, like Dell and Antonina, to act boldly and survive.

Antonina Rossi (“The Antidote”)

Antonina Rossi, known professionally as “The Antidote,” is perhaps the most complex and morally burdened character in The Antidote. As a prairie witch who once ran a business allowing people to deposit and retrieve memories via a magical earhorn, she is both a healer and an instrument of systemic violence.

Her body has served as a vault for others’ pain, confessions, and crimes, making her both repository and prisoner of communal suffering. Her “bankruptcy” on Black Sunday, when all the stored memories vanish, parallels the Dust Bowl’s physical erasure of the land.

Yet it also signals a deeper spiritual disintegration—her own self has been so overwritten that her identity becomes fragile and fragmented.

Her entanglement with Sheriff Vick Iscoe exposes the novel’s darkest truths. He uses her services to manipulate the legal system, suppress dissent, and even violate her body under the guise of power.

Antonina’s silence during these abuses is not consent but survival, a strategy that belies the immense courage it takes to endure. Her internal struggle is marked by remorse, particularly in her failure to protect Zintka, a girl she loved and admired.

She begins to question whether her memory work has served healing or merely helped powerful men rewrite history. In her bond with Dell, Antonina finds a chance at partial redemption.

As she apprentices Dell and confronts her own past—especially her grief over the son taken from her—Antonina begins the long, painful journey from complicity to resistance. Her final communion with her son’s memory suggests a possibility of rebirth through remembrance, not erasure.

Sheriff Vick Iscoe

Sheriff Vick Iscoe embodies the oppressive forces of patriarchy, racism, and state violence that course through The Antidote. Charismatic on the surface, he masks profound brutality beneath a veneer of public duty.

As both enforcer of the law and its most frequent abuser, Vick manipulates truth to consolidate power. He orchestrates the framing of Clemson Louis Dew as the Lucky Rabbit’s Foot Killer, planting fake evidence and exploiting Antonina’s memory-banking to falsify testimonies.

His desire for control extends to physical violation: his rape of Antonina is an ultimate act of domination, cloaked in warped affection.

Vick’s terror lies in his capacity to convince others of his righteousness while committing unspeakable crimes. He is not just a personal villain but a systemic one—a product and perpetuator of institutional rot.

His encounter with supernatural forces during the final storm strips him of this manufactured authority. The image of him blinded by a scarecrow’s hat and fleeing into the dust illustrates not only a physical defeat but a symbolic one: the land and its truth have risen against him.

Yet the fact that Vick is not killed, but shamed and repelled, reflects the novel’s nuanced depiction of justice—not always punitive, but always revelatory.

Clemson Louis Dew

Clemson Louis Dew is less a fully developed character than a symbol of collective guilt and miscarriage of justice. Convicted of murdering Dell’s mother and executed in a spectacle of state violence, Dew remains a spectral presence in the narrative.

His physical attributes—his stutter, cracked glasses, and vulnerability—stand in stark contrast to the monstrous image painted by the town. Through Dell’s reflections and eavesdropping, readers are invited to question whether Dew was truly guilty or simply convenient.

His execution, particularly the failure of the electric chair, becomes a grotesque performance that underscores the inhumanity of the justice system. Dew’s memory haunts Dell, not just as a personal mystery, but as a moral indictment of how fear, prejudice, and silence can kill the wrong man.

Zintkala Nuni (“Zintka”)

Zintkala Nuni, or Zintka, represents the intersecting traumas of colonial violence, racial erasure, and institutional control. A Lakota child stolen from Wounded Knee and paraded as a war trophy, her life is defined by forced assimilation and incarceration.

Despite relentless abuse—from suffragette saviors to state homes—Zintka resists with fierce intelligence and pride. Her bond with Antonina is emotionally rich but fraught; Zintka is betrayed by Antonina’s failure to defend her in a critical moment.

Still, her legacy looms large in Antonina’s conscience and the narrative at large. Zintka’s life is a testimony to both resilience and the high cost of silence.

She embodies the question the novel keeps asking: What is remembered, and who gets to forget?

Cleo Allfrey

Cleo Allfrey, the photographer and chronicler, operates at the margins of power yet becomes crucial in capturing and preserving truth. Through her camera, she documents both the horrors and the hopes of the narrative’s unfolding.

She is witness to Antonina’s suffering and Harp’s confession, and her work represents an alternative form of memory banking—one rooted in vision rather than voice. Her refusal to flee, her protection of Antonina, and her confrontation with Vick signal a moral awakening.

Though her camera is destroyed, Cleo’s act of bearing witness stands as a defiant gesture against oblivion. In the final scenes, she becomes one of the women co-creating a future founded on accountability, solidarity, and survival.

Themes

Memory as Burden and Repository

Memory functions not only as a source of personal history but as a communal force that defines identity and enforces accountability in The Antidote. The witch’s role as a human Vault—capable of storing and recalling others’ memories—makes her both a guardian and prisoner of a collective past.

Her body becomes a living archive of atrocities, confessions, regrets, and lost joys, and this embodiment is not symbolic but physical: she carries weight, illness, and psychic deterioration from the memories she has absorbed. The idea that memories are not contained solely in the brain but are distributed throughout the body complicates the concept of erasure.

Even when memories are withdrawn or artificially altered, they linger in the body’s tension, illness, and shame. When the Vault collapses on Black Sunday and her memories are lost, the resulting void reflects the ecological and societal collapse around her.

This absence is not a relief, but a terrifying disconnection from meaning. The witch’s yearning to recover memory is not nostalgia—it is a cry for moral continuity and justice.

Memory, even when painful or incomplete, is necessary for truth to persist and for healing to begin. The story warns against the desire to forget, revealing that erasure—whether magical or institutional—ultimately leads to further violence and disorientation.

The people of Uz may want to forget their complicity or their pain, but the earth, the body, and the story itself refuse to allow them to do so.

Generational Trauma and Historical Complicity

The violence of the past reverberates across generations, shaping not only individual psyches but communal structures in The Antidote. Harp Oletsky’s childhood memory of the jackrabbit culling becomes emblematic of this theme.

That act of mass killing—sanctioned and normalized by adults—lays the groundwork for the moral numbness and institutional cruelty that permeates Uz. Harp, who never fully processes his trauma, passes on unresolved guilt and emotional rigidity to his niece Dell, who grows up in an environment defined by silence, grief, and emotional absence.

Dell’s life is shaped by her mother’s murder and her community’s refusal to question the official narrative, creating a void where truth should be. This intergenerational trauma is not merely psychological; it is reflected in the land itself.

The Dust Bowl, a product of ecological exploitation and industrial arrogance, mirrors the moral desolation of a town that thrives on erasure and exclusion. When Harp exposes the town’s founding theft of Pawnee land and its historical pact of silence, he is not just confronting contemporary corruption but naming the original sin from which all others descend.

The townspeople’s violent backlash shows how fiercely societies defend their sanitized myths. Trauma, then, is not only inherited biologically or emotionally—it is reinforced by systems, retold through lies, and punished when challenged.

The story confronts the reader with a brutal question: who benefits from forgetting, and who suffers because of it?

Institutional Cruelty and Gendered Power

Institutions in The Antidote—from sheriffs’ offices to orphanages and medical wards—operate less as protectors of order and more as enforcers of silence and suffering. Sheriff Vick Iscoe’s manipulation of the witch, his brutal cover-ups, and his sexual violence exemplify how power justifies itself through righteous performance while committing atrocities in the shadows.

His use of the witch to fabricate or erase memories turns a sacred, feminine act—memory-keeping—into a tool of control. His repeated assault cloaked in a performative tenderness reveals how language is weaponized to distort meaning and mask harm.

Similarly, the institutionalized girls like Zintka and Toni are subjected to physical restraint, surveillance, and psychological degradation, often framed as “rehabilitation” or “reform. ” Zintka’s story, in particular, exposes how colonial violence persists through the assimilationist machinery of boarding schools and state guardianship, robbing Indigenous girls of identity and agency.

Even those who survive do so at immense personal cost, often forced into complicity. The sexual exploitation of Ellda, who trades her body to secure a bus ride for her team, speaks to the dire economic and social conditions that compel girls to sacrifice autonomy for communal survival.

These violences are not isolated events but institutional habits. The story portrays women not as passive victims but as agents negotiating impossible conditions, often turning the same tools used against them—like the earhorn or the camera—into instruments of resistance.

But the cost of resistance is always high, measured in scars, silence, and strategic surrender.

Resistance and Feminine Solidarity

Resistance in The Antidote emerges not as a singular act of heroism but as a pattern of quiet, cumulative choices made mostly by women. Whether it’s Toni deciding to stay and fight rather than run, Cleo documenting abuses through photography, or Dell transforming her grief into a source of spiritual strength, the women in the story model endurance that is political as well as emotional.

The witch’s moral awakening and refusal to continue fabricating memories mark a crucial shift—from complicity to active defiance, despite the personal danger it invites. Solidarity, while imperfect and at times fraught with betrayal, becomes a lifeline.

Dottie Iscoe’s contradictory treatment of the witch illustrates how even tenuous alliances can become critical when navigating patriarchal violence. The final stand in the root cellar, where generations of women and girls shelter together, is not just a moment of refuge but one of redefinition.

They are no longer isolated figures on the margins but a collective asserting a claim to truth, survival, and future. Feminine power here is neither mystical nor idealized—it is grounded in resilience, caretaking, and mutual recognition.

The birth of kittens, the basketball championship, and the miracle of the wheat are all symbolic gestures of continuity, showing that life endures not through dominance but through connection. These acts of resistance—some public, others private—offer a vision of hope that resists false absolution.

They suggest that the antidote to collapse is not forgetting, but remembering together.

Moral Ambiguity and the Cost of Truth

Truth in The Antidote is unstable, often distorted by power, self-interest, or the limits of memory. Clemson Louis Dew’s wrongful execution becomes a narrative pivot around which questions of guilt, justice, and narrative manipulation swirl.

Dell’s uncertainty about Dew’s culpability echoes a deeper unease: how does one pursue justice in a world where institutions lie and memories are malleable? Even the witch—tasked with safeguarding others’ truths—questions the morality of her own role, especially as she recalls her failure to protect Zintka or to resist Vick’s coercion earlier.

Harp’s speech, which bravely exposes the founding myths of Uz, is both necessary and self-sabotaging. It speaks to the painful paradox of truth-telling: those who illuminate uncomfortable histories are rarely rewarded and often attacked.

The mob’s swift turn from sympathy for Clemson to rage at Harp reflects a communal preference for convenient lies over destabilizing truth. Even within the team of girls, truth is bartered—Ellda’s silent sacrifice remains mostly unacknowledged.

The story asks whether honesty, especially about historical wrongs, can coexist with community, or whether it inevitably isolates the speaker. And it does not offer easy answers.

Instead, it insists on truth’s costliness and necessity. To tell the truth in this world is to risk violence, rejection, and loneliness.

But it is also the only way to stop the cycle of forgetting that leads back to cruelty. In that sense, the antidote is not forgiveness or vengeance, but the fragile, persistent act of remembering what the world would rather erase.