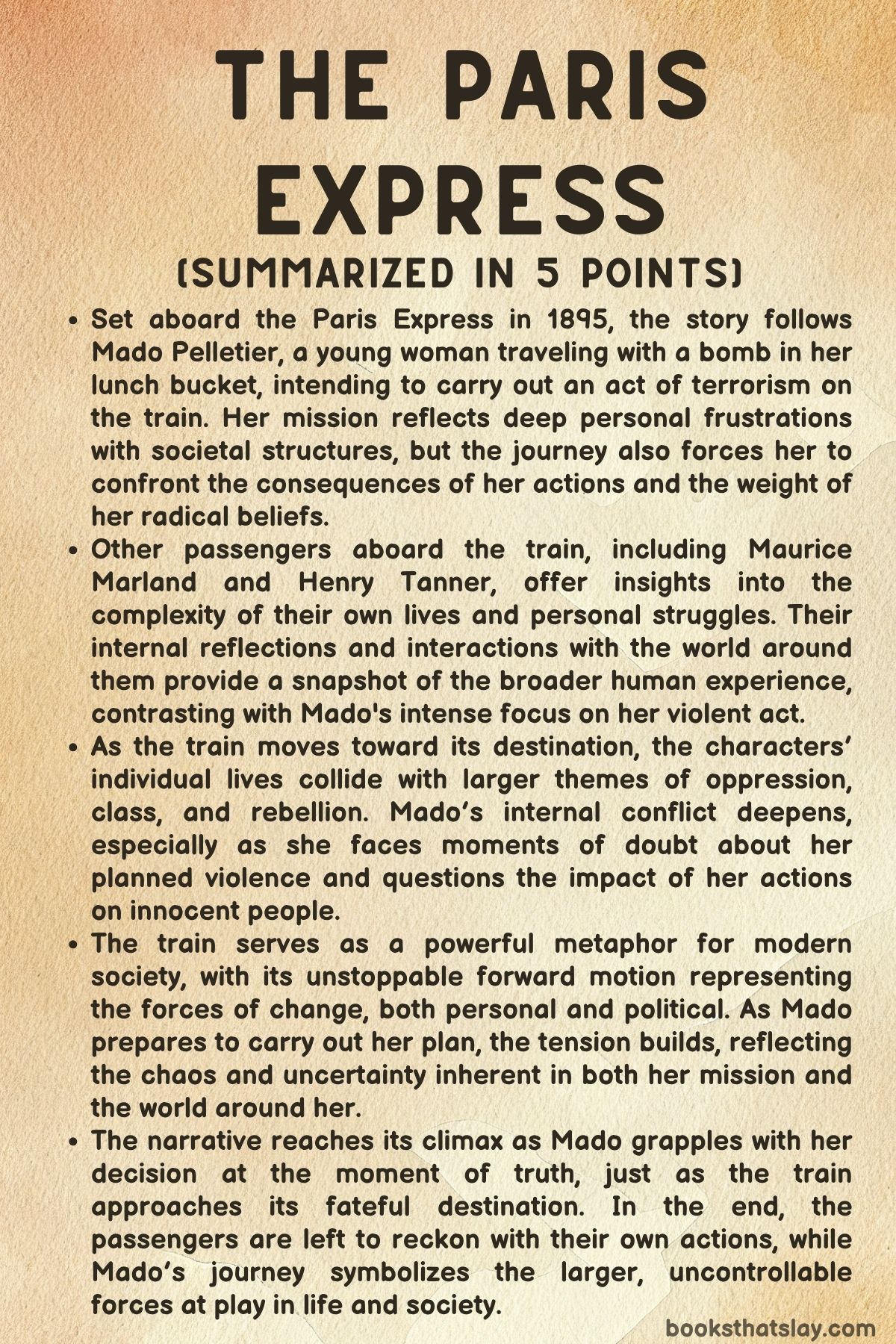

The Paris Express Summary, Characters and Themes

The Paris Express by Emma Donoghue is a tense narrative set aboard a train journey in 1895. The novel explores the lives of a diverse group of passengers on the Paris Express, highlighting themes of political unrest, personal conflict, and societal divides.

Central to the story is Mado Pelletier, a young woman driven by anarchistic ideals, who carries a bomb in her lunch bucket with plans to target political figures. As the journey unfolds, her inner turmoil, along with the personal stories of other passengers, intertwines with a dramatic and tragic event, revealing the fragility of human lives and the tension between rebellion and the impact of choices.

Summary

The novel begins on the morning of October 22, 1895, at Granville Station, located on the Normandy coast. Mado Pelletier, a 21-year-old woman, stands outside the station in androgynous clothing, preparing for her journey back to Paris.

She arrives from Paris on the down train the day before, and although she could leave later, she is determined to catch the Paris Express by lunchtime. This rare trip to Granville represents a brief escape from her mundane life in the greengrocery her family runs in Paris, a life overshadowed by her mother’s grief and the weight of family responsibility.

Mado, rejecting societal norms regarding gender and femininity, embraces a life outside traditional female roles. She is deeply critical of the societal expectations placed upon women, feeling suffocated by them.

As Mado observes the people around her, she notes a small boy who imitates her stillness, and she reflects on the judgments she faces for her appearance, especially her short hair and gender-neutral attire. Her train of thought is interrupted by a man on a bicycle, who glances at her with a smirk, reminding her of the oppressive societal gaze she constantly faces.

Mado’s background, shaped by the hardships of her working-class family, fuels her suspicion of a system that seems to entrap people like her, particularly women, in cycles of poverty and inequality.

When the train departs, the focus shifts to several other passengers. Maurice Marland, a young boy traveling alone for the first time, reflects on the strange difference between two clocks at the station, contemplating the absurdity of time.

Henry Tanner, an American artist traveling in second class, observes the fleeting nature of time as he watches the landscape pass by. The narrative provides glimpses into their internal thoughts and the ways in which the train journey becomes an introspective moment for each of them.

Mado’s internal conflict deepens as she grapples with her anger toward the system. She rejects the conventions that confine her, but her resolve is also tested as she contemplates the consequences of her actions.

Her thoughts on class, gender, and identity are contrasted with the mundane exchanges around her. A conversation between Maurice and a priest about time reveals the complexities of human perception and modernity’s effect on experience.

Meanwhile, Mado’s discomfort in the cramped Third-Class carriage grows, and she clutches her lunch bucket—a symbol of her rebellion—tightly. This lunch bucket holds the bomb she meticulously crafted, designed to bring destruction to the oppressive political figures she blames for the suffering of the working class.

Her anger toward the system has pushed her to the edge of violence, and the train journey becomes symbolic not only of physical movement but of her emotional journey toward a decision she feels is necessary for societal change.

As the train moves toward its destination, Mado’s resolve hardens, and she reflects on her carefully laid plans. She intends to detonate the bomb when the train reaches Briouze, where a political deputy she has targeted will be on board.

Her thoughts grow more intense, driven by her belief that only radical action can shake the oppressive system that she feels exploits people like her.

The narrative switches between the lives of other passengers. Léon Mariette, a train guard, deals with the logistics of the journey, reminding himself of the importance of safety and order, even as the physical strain of his work wears him down.

Alice Guy, a secretary, experiences the tension of her subordinate position as she travels with her boss, while Marcelle de Heredia, a young woman engrossed in academic studies, finds solace in the distraction of her work. These characters’ experiences offer insight into the lives of those aboard the train and the different roles they play in a society divided by class and power.

The tension builds as Mado’s plan to target the deputy draws closer. The weight of her decision, as well as the emotional turmoil she faces, amplifies the stakes of the journey.

As the train nears Briouze, Mado’s thoughts and feelings about her mission intensify, and she struggles to reconcile her belief in violent revolution with the reality of innocent lives affected by her actions.

Simultaneously, Cécile Langlois, a pregnant woman traveling on the train, goes into labor. Her suffering contrasts with Mado’s cold resolve.

Mado, who had initially been focused solely on her plan for violence, is suddenly confronted with the reality of life and death. She finds herself at a crossroads when Cécile gives birth prematurely, and Mado, in an unexpected turn of events, begins to question her motivations.

She feels a sense of personal failure, grappling with her desires for glory and martyrdom, and the realization that her grief stems from her own vanity.

As the train hurtles toward its destination, a mechanical failure strikes, and the train is unable to stop. Panic spreads among the passengers as the collision with Montparnasse Station seems inevitable.

The passengers’ reactions reflect a mixture of fear, confusion, and desperation. In the chaos, Mado makes the decision to abandon her plan, unable to go through with the bombing.

Instead, she assists with the birth of Cécile’s child, experiencing a moment of connection with life amidst the impending disaster.

In the final stretch of the journey, the train crashes through the station platform, causing widespread destruction. The only fatality is a newspaper seller who happens to be standing beneath the station when the train bursts through the façade.

The crash serves as a symbol of industrial power and the fragility of life, highlighting the randomness of fate and the way individuals confront mortality. Survivors, including Mado, reflect on their near-death experiences, realizing that their lives, like the train, have been propelled forward by forces beyond their control.

In the aftermath of the crash, the characters are left to confront their choices. Mado, who once sought revolutionary change through violence, finds herself at a crossroads.

The bomb she had intended to use lies unused, and the birth of Cécile’s child serves as a stark contrast to the destruction she had planned. The train journey, with all its personal dramas, ultimately becomes a metaphor for the chaotic, unpredictable forces that shape human lives.

The narrative closes with a reflection on the randomness of life, fate, and the consequences of the choices we make.

Characters

Mado Pelletier

Mado Pelletier is the central figure in The Paris Express whose internal conflict and radical beliefs drive the narrative. A 21-year-old woman, Mado stands outside Granville Station in androgynous clothing, embodying her rejection of conventional femininity and societal norms.

Raised in a working-class environment, Mado is burdened by the weight of family responsibility and her mother’s grief. These hardships shape her view of the world, cultivating a deep disdain for the social systems that oppress people like her.

Her appearance, particularly her short hair and gender-neutral attire, makes her a target for judgment, and she navigates the world with a sense of defiance against societal expectations of marriage, gender roles, and conformity. As she travels aboard the Paris Express, Mado is on a mission that goes beyond physical movement—it is an emotional and ideological journey.

She has prepared a bomb in her lunch bucket with the intent to commit an act of violence against those she sees as oppressors. Mado’s deep-seated anger towards the rich and powerful, whom she perceives as exploiting the poor, drives her toward radical action.

However, her inner turmoil becomes apparent as she grapples with the moral implications of her plan. Despite the certainty of her cause, Mado faces the haunting reality of what her actions could mean for innocent passengers, like Cécile Langlois, and the weight of her own ideological conflict.

Her evolution from cold resolve to a moment of personal failure and redemption highlights the complex tension between individual desire and societal pressures.

Maurice Marland

Maurice Marland is a young boy traveling alone for the first time on the Paris Express. His presence offers a lens through which the passage of time and human experience are reflected.

Maurice is keenly aware of the differences between the clocks at the station, an innocent observation that hints at his broader contemplation of time, the absurdities of life, and human existence. His thoughts, seemingly simple, are infused with a deeper questioning of the world around him.

Maurice represents a juxtaposition to the adult passengers, embodying innocence and the pure curiosity of youth. His experiences on the train, however, are shaped by more than just the immediate journey.

Maurice’s perspective adds a layer of complexity to the narrative, symbolizing the transition from childhood to adulthood, and how individuals encounter the world with a mix of wonder and confusion as they grow older.

Henry Tanner

Henry Tanner, an American artist traveling in second class, is a reflective figure whose inner world contrasts sharply with the frenetic pace of the external journey. As he watches the changing landscape from the train, Tanner contemplates the fleeting nature of time, mirroring the transient nature of the train journey itself.

His observations on the passage of time and the impermanence of human existence speak to the larger themes of modernity and the inevitable changes that accompany it. Tanner is more of a passive observer in the narrative, removed from the active tensions aboard the train.

His focus on the world around him, particularly on the physical movement of the train and the changing landscape, illustrates a character deeply connected to the rhythms of nature and art. His reflections offer a contrast to the more urgent, political motivations of characters like Mado, serving as a reminder of the quieter, more contemplative ways in which individuals experience life.

Léon Mariette

Léon Mariette is the train guard who plays a crucial role in ensuring the smooth operation of the journey. His work, which requires constant vigilance and attention to detail, is punctuated by the monotonous strain of his daily duties.

Though he upholds the importance of safety and order, Mariette is plagued by the physical exhaustion and the mind-numbing repetition of his tasks. His reflections on the mechanics of his job reveal his deep connection to the train as a symbol of industrial progress, even though he feels trapped within the confines of the rigid system he helps maintain.

Léon represents the working-class figures who are often unnoticed in the grand narrative of social change, yet whose labor is integral to the functioning of the very systems that affect everyone on board. His internal struggle, marked by both a sense of duty and a desire to break free from his routine, provides insight into the lives of those who serve without question, often for a system that does not acknowledge their personal desires or well-being.

Alice Guy

Alice Guy, a secretary traveling with her boss, embodies the professional tensions of the late 19th century. Her character offers a window into the subtleties of power dynamics in the workplace, as she navigates the complexities of her relationship with her employer.

Alice is caught in the quiet struggle between her role as a subordinate and the desire to assert herself within the confines of a rigid social structure. Though her role on the train may seem peripheral to the central plot, her thoughts reflect the broader themes of gender and power, as well as the limitations placed on women during the period.

Alice’s journey, while physically on the train, is also one of self-awareness, as she reflects on the confines of her professional life and the quiet rebellions that women often face in the pursuit of personal agency.

Marcelle de Heredia

Marcelle de Heredia is a young woman engrossed in her academic work, representing the intellectual class on the train. Her focus on her studies provides her with a temporary escape from the social tensions and complexities that surround her.

Marcelle’s concentration on her academic pursuits highlights the role of education and intellect as a means of finding solace amidst a world filled with chaos and uncertainty. However, her intellectual escape also contrasts with the revolutionary energy embodied by characters like Mado, suggesting a divide between those who seek refuge in personal pursuits and those who are driven to take radical action to challenge the world around them.

Marcelle’s character reflects the ways in which individuals seek personal meaning and fulfillment, often turning to their intellectual or professional ambitions as a way to distance themselves from the political and social strife unfolding in the larger world.

Blonska

Blonska, an older woman who has witnessed the ravages of time and change, serves as a poignant reflection on the cost of radical ideologies and the long-lasting effects of personal history. Having lived through various periods of upheaval, Blonska is acutely aware of the implications of Mado’s radical intentions.

She feels a mixture of fear and sympathy for Mado, recognizing both the girl’s misguided passion and the pain that fuels her actions. Blonska’s thoughts on revolution and making a difference are steeped in the wisdom of age, offering a counterpoint to Mado’s youthful idealism.

Her reflections highlight the generational divide between those who have seen the consequences of radical change and those who still believe in the power of revolutionary action. Blonska’s internal conflict, as she grapples with whether to expose Mado’s plan, further emphasizes the theme of moral ambiguity and the question of what one should do in the face of potential disaster.

Her character represents the quieter, more reflective approach to societal change, as she tries to reconcile her own life experiences with the present moment of crisis.

Cécile Langlois

Cécile Langlois is a pregnant woman traveling aboard the train, and her experience on the journey introduces a contrasting theme to Mado’s radicalism. As Cécile experiences the pain of premature labor, her personal crisis highlights the human side of the story, where individual suffering is intertwined with the larger societal tensions at play.

Cécile’s condition, marked by the impending birth of her child, stands in stark contrast to Mado’s destructive mission, offering a reminder of the fragility of life and the cyclical nature of existence. In the midst of Mado’s violent intentions, Cécile’s labor serves as a moment of life and hope, symbolizing the continuation of the human race despite the chaos that surrounds it.

Her role in the narrative underscores the theme of birth and renewal, providing a grounding force in the midst of the political and ideological currents that drive the other characters.

Themes

Class and Social Inequality

The theme of class and social inequality is at the forefront of The Paris Express, especially as it relates to Mado Pelletier’s character. Mado, raised in a working-class environment and burdened by the responsibilities of running her family’s greengrocery in Paris, develops a deep distrust of the societal systems that keep people like her trapped in poverty.

Her journey represents more than a physical move from Granville to Paris—it reflects her desire to escape the limitations of her social class and the oppressive roles society imposes, particularly on women. Mado’s rejection of conventional femininity and the rejection of the traditional paths that women in her class typically follow, such as marriage and motherhood, exemplifies her broader disdain for a system that marginalizes people based on their economic and social status.

This theme runs parallel to the other passengers aboard the train, who are also defined by their place in the social hierarchy, from Maurice Marland’s youthful innocence to the more privileged American artist Henry Tanner. The train itself, symbolizing the very systems of modernity, progress, and state control, becomes a tool of oppression for Mado.

The contrast between Mado’s revolutionary fervor and the relatively ordinary, privileged lives of many of the other passengers highlights the stark divisions between social classes, reinforcing the book’s exploration of societal exploitation.

Radicalism and Political Rebellion

Mado’s internal conflict regarding radicalism and her belief in political rebellion form the core of her character’s psychological journey in The Paris Express. Mado’s anarchistic ideology is driven by a belief that violence is the only way to combat the injustices she perceives around her.

She sees herself as a martyr, willing to sacrifice herself for the greater good, targeting those she believes uphold the oppressive systems of government and capitalism. Her carefully planned bombing is meant to send a message to the political figures she perceives as responsible for the suffering of the working class.

However, as the narrative unfolds, Mado’s internal struggle becomes increasingly evident. Her act of violence, meant to bring justice to those who suffer in poverty, is at odds with her own growing sense of personal failure, vanity, and the recognition that innocent lives would inevitably be caught in the crossfire.

This conflict between her radical beliefs and the human cost of those beliefs is amplified by her interactions with the other passengers, especially those who represent the very structures she opposes. The tension between the necessity of revolution and the reality of its consequences provides the emotional depth of the story.

Identity and Gender

Gender identity and societal expectations of femininity and masculinity play a critical role in shaping the narrative of The Paris Express, particularly through Mado Pelletier’s character. Her rejection of traditional gender roles—represented by her choice of androgynous clothing and short hair—places her in direct opposition to the conventional ideas of what a woman should be in the late 19th century.

Her appearance invites judgment and exposes the harsh scrutiny that women, especially those who defy societal norms, face in a patriarchal society. Mado’s struggle with her own identity is compounded by the pressures from her family and society to adhere to prescribed roles.

This theme extends to her interactions with others, such as the fleeting moment of connection she feels with a young boy who imitates her stillness, highlighting how gender norms are internalized and mirrored in others. Mado’s resistance to these expectations is a key aspect of her character, yet the story suggests that her defiance is both a source of empowerment and isolation.

As the narrative progresses, Mado’s emotional growth is marked by her increasing recognition of the role that gender plays in shaping her destiny and her decisions.

Fate and Human Mortality

The theme of fate and human mortality is central to the story’s climax, where the journey toward Montparnasse station becomes a metaphor for the inevitability of life and death. Throughout the narrative, the passengers grapple with their mortality in different ways.

Mado, once resolute in her desire for violence, begins to question the consequences of her actions and the potential harm to innocent lives, illustrating her growing awareness of the fragility of life. This theme is underscored by the events surrounding the premature birth of Cécile Langlois’s child and the tragic Montparnasse derailment.

The derailment, though an accident, forces the characters to confront their own survival, with some like Mado reflecting on the randomness of life and death. The train itself, a symbol of progress and human control, is helpless in the face of mechanical failure, emphasizing the futility of trying to control one’s fate.

As the story moves toward its conclusion, the characters’ reflections on the randomness of their survival underscore the vulnerability of human existence. The train’s collision with the station, causing chaos and destruction, mirrors the unpredictable nature of life and the inescapable forces that guide individual destinies.

Human Connection and Compassion

Despite the overarching themes of rebellion, violence, and societal critique, The Paris Express also delves deeply into the theme of human connection and compassion. This theme is most powerfully embodied in Mado’s eventual decision to abandon her plan for terrorism and assist Cécile during the birth of her child.

Initially, Mado is consumed with anger and frustration, her vision clouded by the perceived injustices of the world. Yet, in a moment of profound vulnerability, she shifts from her revolutionary zeal to a more personal, human act of kindness.

This act of compassion reveals Mado’s capacity for empathy and suggests a deeper conflict within her: a yearning for connection that is at odds with her radical beliefs. The narrative juxtaposes these personal moments of connection with the broader social tensions that Mado faces, illustrating how human connection can act as a counterbalance to the alienation fostered by societal pressures.

The bond between individuals, even in the most dire of circumstances, emerges as a powerful force, providing an alternative to the violence and rebellion that Mado had once seen as the only solution to her grievances. This shift in Mado’s character highlights the potential for transformation and redemption, even in the face of overwhelming adversity.