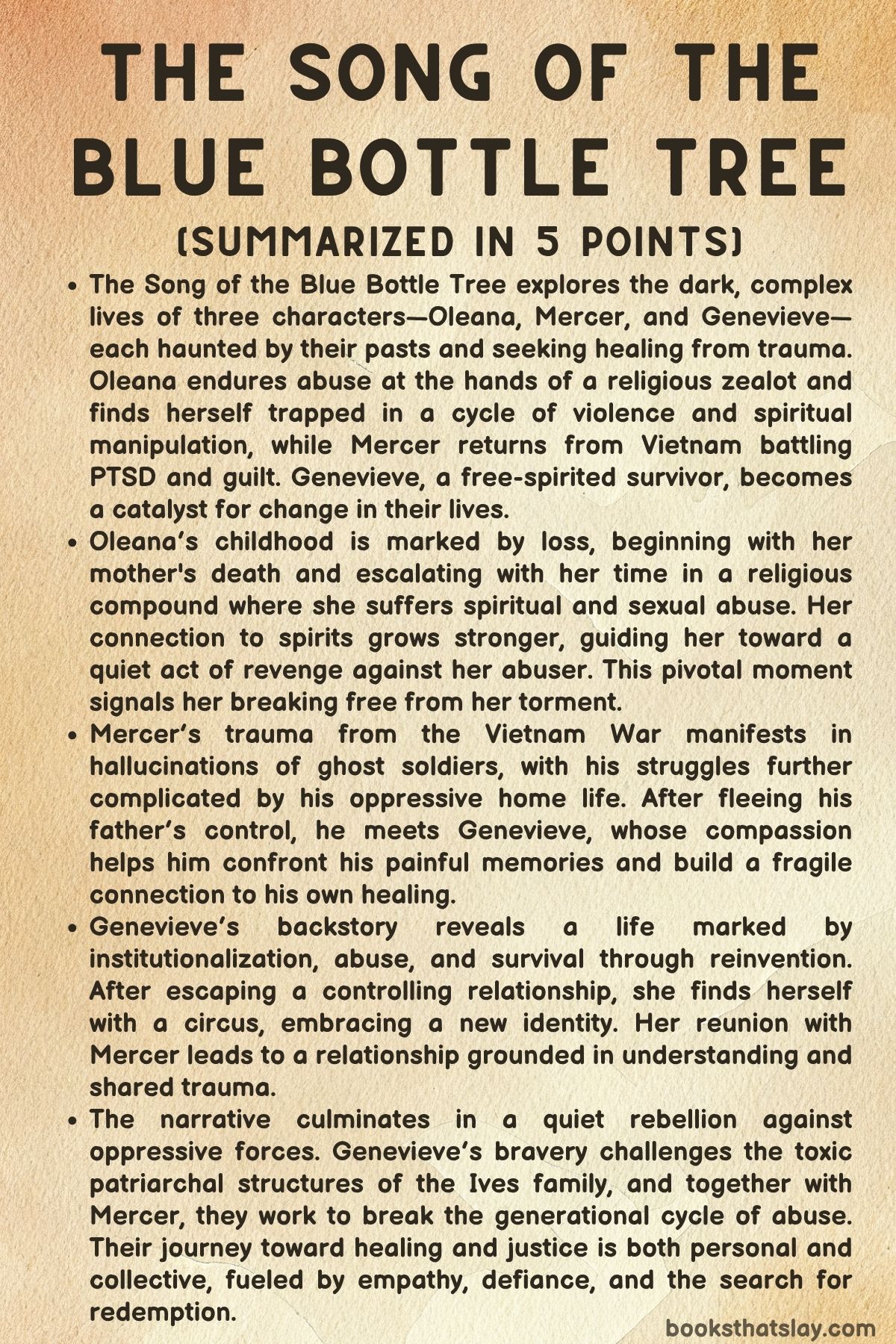

The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree Summary, Characters and Themes

The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree by India Hayford is a sweeping Southern Gothic novel about inherited trauma, spiritual resistance, and the desperate search for safety and selfhood. Told through a chorus of voices—children and adults, the living and the dead—it explores the lives of Oleana, Mercer, Genevieve, Wreath, and Jezzie, all of whom carry burdens shaped by abuse, abandonment, and religion gone wrong.

Set across a haunted American South, the story exposes the corrosive power of patriarchal control and spiritual manipulation while holding up defiant love, chosen family, and resilience as the path to healing. It is as much a ghost story as it is a reckoning.

Summary

The story begins with twelve-year-old Oleana, whose life is marked by physical awakening and a spiritual sensitivity to ghosts. After her mother’s death, she lives with her eccentric but loving grandmother Meema in Arkansas.

Oleana begins menstruating and simultaneously starts hearing spirits call her name. Meema dies after her house is destroyed in a tornado and her spirit is broken.

With her father unwilling to care for her, Oleana is placed in the custody of Reverend Burgess Darnell and his mother Aunt Nette in a religious compound called Kingdom Come in Alabama. What follows is a harrowing stretch of spiritual and sexual abuse, wrapped in a grotesque interpretation of Christian practice—complete with snake-handling, violent sermons, and fear-mongering.

The ghost of Mara, a woman who died during a church service, haunts Oleana and helps guide her through the horror. Eventually, she quietly kills Burgess with a rattlesnake in an act of supernatural vengeance, driven by her psychic connection with the dead and her grandmother’s ghostly encouragement.

The narrative shifts to Mercer, a young Vietnam veteran suffering from PTSD and hallucinations, especially of a ghost-soldier named Bigger Than You. Mercer returns to his family home in Louisiana, only to find the same kind of controlling religious environment that exacerbated his trauma.

His father, John Luther Ives, is a preacher with a dominating personality. Mercer cannot endure the emotional suffocation and flees into the wilderness.

In a cemetery, he meets Genevieve, a woman who also hears the dead. She tends to Mercer’s physical and emotional wounds and encourages him to reconnect with his mother Wreath, who has long suffered under John Luther’s rule.

Genevieve’s past is marked by institutionalization after a mental breakdown and abuse from a controlling lover. She adopts the name Genevieve from a dead baby’s gravestone and reinvents herself through a traveling circus, where she works as a snake dancer and trapeze artist.

Despite her hard past, she remains strong, defiant, and fiercely empathetic. She moves into the Ives household and soon witnesses the abusive dynamic firsthand.

John Luther is immediately threatening, particularly toward Wreath, whose entire married life has been shaped by coercion and submission. Genevieve intervenes when John Luther tries to beat Wreath, throwing a rock through a window to stop him, risking her safety in the process.

Wreath’s backstory is detailed in parallel. Once a radiant Southern girl, she is seduced and raped by John Luther during their courtship under the guise of a religious ritual.

Pregnant and ashamed, she is pressured into marrying him, a decision that leads to years of abuse, emotional suppression, and the gradual destruction of her spirit. Her children, including Mercer and Jezzie, grow up in this atmosphere of control and fear.

Genevieve becomes a source of strength for Wreath, helping her reflect on her past and confront the legacy of abuse.

Genevieve and Mercer grow closer, sharing moments of vulnerability and recognition. Their bond deepens when Genevieve, determined to go to college, begins dancing again to pay tuition.

Despite Mercer’s offer to support her financially, she insists on keeping her independence. When she is violently targeted—her apartment trashed and her possessions destroyed—Mercer becomes more protective, recognizing how deeply he cares for her.

Genevieve breaks down emotionally during one of her dance performances, overwhelmed by trauma and dissociation. Mercer brings her home, and she starts to reclaim her agency with his quiet support.

Delilah, a cousin in the Ives family, offers her perspective next. Her jealousy and sanctimony are rooted in her own history of childhood abuse, where she was trained in “wife lessons” by her father.

Delilah sees Genevieve as a threat to the family’s status quo. Meanwhile, Genevieve finds peace in the ruins of Meema’s old farm, where she speaks with the ghost of Bigger, Mercer’s wartime companion.

The encounter strengthens her resolve and confirms her spiritual gifts.

Jezzie, now a teenager, becomes the next flashpoint. John Luther plans to force her into an arranged marriage and pull her out of school.

When she resists, he assaults her and drags her home. That night, during a storm, he drags her to the church for a deranged ritual to resurrect the dead.

There, he is bitten by a rattlesnake—mirroring Mara’s earlier death—and dies. Jezzie escapes into the storm while Genevieve and Mercer search for her.

Meanwhile, Wreath fights off her husband to protect Jezzie, sustaining injuries but rediscovering her own agency.

After John Luther’s death, the community covers up the incident as an accident, unwilling to acknowledge the truth. Delilah tries to claim control with a supposed will, only for Wreath to reveal it was just a pie recipe.

Wreath reclaims the home and begins rebuilding her life. Jezzie changes her name to Jessica, symbolizing rebirth.

Genevieve inherits Meema’s farm and forms a chosen family with Mercer, Jessica, and Wreath. Young Leah, another child in the family, recognizes Genevieve as a force of goodness and burns the false will, affirming the end of John Luther’s legacy.

In the final scenes, Mercer honors his fallen friend Bigger with a quiet, personal ritual. The family gathers for a picnic—simple, joyous, and real.

Though their scars remain, they have broken the cycle of violence. Healing comes not from institutions or grand resolutions but from love, resistance, and standing up for one another in a world that too often punishes the vulnerable.

Characters

Oleana

Oleana is the emotional and spiritual heart of The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree, and her journey from innocence to haunted resolve forms one of the novel’s most visceral arcs. Initially introduced as a twelve-year-old on the cusp of bodily and psychic awakening, Oleana lives in the sanctuary of her grandmother Meema’s Arkansas farmhouse, where eccentricity and spiritual openness provide a buffer against the harsher realities of the outside world.

Her gift—or curse—of hearing the dead marks her early as a liminal figure, one who straddles the natural and supernatural. When Meema dies, both literally through a tornado and figuratively from heartbreak, Oleana is cast into a cruel and unforgiving world.

Her father’s refusal to take her in forces her into the clutches of Burgess Darnell and Aunt Nette, whose religious compound, Kingdom Come, becomes the site of her spiritual, emotional, and sexual torment. There, her psychic sensitivity intensifies, not just as a tool of horror but as a lifeline to power and resistance.

Oleana’s growth is painful but unflinching; her eventual act of vengeance—covert and poetic—becomes a reclamation of agency in a world that sought to obliterate her.

Mercer

Mercer is a man haunted by war, dogma, and the contradictions of masculinity in the post-Vietnam South. As a former Navy corpsman, he returns home burdened by PTSD and literal ghosts, including a spectral soldier named Bigger Than You who serves as both tormentor and companion.

Mercer’s psychological fragmentation is exacerbated by his father, John Luther, a brutal patriarch whose brand of righteousness leaves no space for vulnerability or healing. Trapped between trauma and religious repression, Mercer’s escape into the wilderness is not a descent but a necessary step toward rebirth.

His meeting with Genevieve marks a shift in his arc—her fierce compassion and otherworldly understanding begin to thaw his emotional paralysis. Despite his confusion and internal conflict, Mercer gradually evolves from passive sufferer to an active protector, especially for Genevieve and Jezzie.

His love is cautious, wounded, and sincere, offering a quiet but profound alternative to the coercive models of masculinity he was raised under. Mercer’s final scenes—where he honors the memory of Bigger and joins in a family celebration—symbolize not an end to his haunting, but a willingness to live with the dead without being ruled by them.

Genevieve

Genevieve is the fierce, untamed soul of the novel, a woman who has stitched together a life from trauma, wanderlust, and stubborn autonomy. Her origins are obscured and self-fashioned; she borrows her name from a tombstone, escapes institutionalization and abuse, and remakes herself through the circus, adopting identities as a snake dancer and fortune teller.

Yet beneath her flamboyant exterior lies a survivor who has never stopped calculating the cost of vulnerability. Genevieve’s compassion is hard-earned and fiercely protective, most vividly demonstrated in her intervention on behalf of Wreath and Jezzie.

She is a woman who chooses empathy not because it is easy, but because she understands its absence. Her relationship with Mercer is tentative, defined not by romance but by mutual recognition of damage and effort.

Even when she strips again to fund her college education, Genevieve insists on her independence, rejecting Mercer’s offers of financial support. Her confrontation with John Luther, her bond with Jezzie, and her conversations with ghosts mark her as both witness and warrior in the intergenerational struggle against violence.

By the novel’s end, Genevieve is no longer rootless—she inherits Meema’s farm and becomes the spiritual matriarch for a reassembled family, binding the living and dead with her unrelenting will.

Wreath

Wreath is a tragic figure, a Southern belle destroyed from within by the very ideals that once crowned her. Her initial persona—charming, devout, proper—belies a deep loneliness and a longing for emotional refuge, which leads her into the arms of the charismatic predator John Luther.

What follows is a cascade of violation: drugged and raped under the guise of “holy communion,” Wreath is coerced into marriage and endures a lifetime of sexual, emotional, and physical abuse, all masked as religious duty. Yet Wreath’s story is not one of passive victimhood.

Her love for her children is visceral and enduring, and her subtle resistance—hiding truths, protecting Jezzie, and finally attacking John Luther to save her daughter—reveals a spine of steel beneath her genteel exterior. Wreath’s transformation after John Luther’s death is quiet but potent.

She dismisses Delilah’s attempted power grab with withering composure and begins to rewrite her family’s story on her own terms. Her storytelling at the end of the novel symbolizes more than healing—it is an act of authorship, of reclaiming narrative power long denied.

Jezzie

Jezzie embodies the ferocious, flailing hope of the next generation. She is Wreath’s daughter and John Luther’s target of increasingly violent patriarchal control.

Her rebellion is not political or even fully conscious—it is a primal, instinctual refusal to accept a future of submission. From her sarcastic retorts to her internal fantasies of revenge, Jezzie’s defiance is deeply human and heartbreakingly youthful.

She dreams of college and freedom, only to be met with the nightmare of a forced marriage and the end of her education. Her abuse at the hands of her father is graphic and relentless, culminating in a surreal and horrific church service where John Luther attempts to force a resurrection miracle.

Despite the terror, Jezzie survives—thanks in part to Wreath and Genevieve—and emerges from the ordeal battered but not broken. Her decision to change her name to Jessica marks a reclamation of self, a symbolic shedding of the violence and control she endured.

Through Jezzie, the novel articulates the brutal costs of silence and the transformative power of resistance, even from someone still on the cusp of adulthood.

John Luther Ives

John Luther is the embodiment of charismatic evil—a man who twists scripture into weaponry and uses religious authority to cloak his sociopathy. As a preacher, he commands obedience through performance and fear, seducing women under the guise of divine calling and punishing dissent with physical brutality.

His domination of Wreath, corruption of Delilah, and abuse of Jezzie are not isolated incidents but part of a systemic, patriarchal structure that thrives on secrecy and shame. John Luther is not merely an abuser; he is a symbol of institutionalized cruelty, of generational trauma sanctified by religion.

His madness culminates in a deranged attempt to raise the dead, where his own delusions lead him to a grotesque death by snakebite—a form of divine retribution that underscores the poetic justice at the heart of the novel. Even in death, his presence looms, but those he tormented find ways to exorcise his memory—not with revenge, but with renewal.

Delilah

Delilah is a study in internalized abuse, a woman who has converted her victimhood into a desperate hunger for control. Raised under the same roof of patriarchal violence as Wreath, Delilah channels her trauma into sanctimony, cruelty, and manipulation.

Her jealousy of Genevieve, her policing of Jezzie, and her obsession with propriety reflect a brittle identity built on repression. Delilah is not merely an enforcer of John Luther’s tyranny—she is its extension.

Yet even in her cruelty, the novel offers glimpses of her own pain: the so-called “wife lessons” she endured as a child suggest a foundation of horror masked by etiquette. In the end, Delilah’s attempt to usurp Wreath through a fake will collapses under its own absurdity, and she is left exposed as both a perpetrator and a casualty of the system she upheld.

Themes

Trauma and Survival

The theme of trauma and survival is deeply woven throughout The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree, as the characters are forced to confront the harrowing effects of abuse, both physical and emotional. Oleana, Genevieve, and Mercer each carry their own burdens of trauma, with their pasts often haunting their present.

Oleana’s experiences in the religious compound, where she endures spiritual and sexual abuse under the guise of religious righteousness, shape her psyche in profound and chilling ways. Her trauma is compounded by the haunting spirits of the dead, which she feels a deep psychic connection to, giving her both a sense of isolation and a link to a larger, mysterious world.

Similarly, Genevieve’s trauma stems from her past in an abusive relationship that left her emotionally scarred. Her time in an institution and her life on the road with the circus are survival mechanisms, allowing her to escape a past full of neglect and control.

Mercer, on the other hand, suffers from PTSD, stemming from his experiences as a Navy corpsman in Vietnam, where he is haunted by the ghosts of his fallen comrades. Each character’s survival is not merely about physical endurance but also about their capacity to cope with the emotional and psychological wounds left by their pasts.

Throughout the narrative, the characters struggle to make sense of their pain, attempting to heal while battling the ghosts of their trauma. The theme of survival here is about finding ways to navigate a life that is forever altered by the past, and each character’s journey is marked by an ongoing process of recovery.

Religious Extremism and Abuse of Power

Religious extremism is a pervasive and destructive force in The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree, manifesting primarily through the character of John Luther Ives, who uses religion as a tool for manipulation, control, and violence. His marriage to Wreath, marked by sexual violence and spiritual justification, is an embodiment of how religious authority can be twisted into a mechanism for abuse.

This theme explores the corrupting influence of power when it is cloaked in the guise of divine will. The religious rituals at Kingdom Come, including snake-handling and grotesque sermons, reflect the extremes to which John Luther goes to assert his dominance over others, manipulating his followers into believing that their suffering is a path to spiritual enlightenment.

The cruelty he inflicts on his family, particularly Wreath and Jezzie, is justified by his perverse interpretation of scripture, creating an environment where abuse is not only tolerated but enforced as a divine mandate. In contrast, Genevieve’s role in confronting this abuse reflects the theme of resistance, as she stands against the toxic and tyrannical power that religion, when misused, can wield.

The theme of religious extremism in the novel serves as a stark commentary on the dangers of unquestioned faith and the devastating consequences of using religion to control, harm, and dominate others.

Generational Trauma and Breaking the Cycle

The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree also explores the theme of generational trauma and the difficult but necessary process of breaking the cycle of abuse. The narrative reveals how the suffering inflicted on one generation often carries over to the next, perpetuating a legacy of pain, silence, and powerlessness.

Wreath, in particular, represents a generation of women who have internalized their subjugation, passing down their own trauma to their children. Her quiet submission to John Luther’s abuse and her failure to protect Jezzie from a similar fate illustrate the insidiousness of generational trauma.

However, the arrival of Genevieve—a woman who has suffered her own traumas but has also learned to fight back—signals the possibility of breaking free from this cycle. Genevieve’s act of throwing a rock through the window to stop John Luther’s abuse of Wreath is a pivotal moment in the narrative, representing not only a physical act of defiance but also the breaking of the generational chain of silence and subjugation.

Similarly, Jezzie’s escape from her father’s abuse and her eventual reclaiming of her identity as Jessica is a key turning point, marking the end of one generation’s trauma and the beginning of healing for the next. The theme of breaking the cycle of abuse highlights the importance of intervention, resistance, and the courage to defy oppressive systems in order to create space for future generations to heal and thrive.

The Haunting Presence of the Past

Throughout The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree, the past is never truly gone; it lingers, haunting the characters and shaping their decisions, relationships, and identities. For Oleana, the past is filled with the spirits of the dead, including the tragic figure of Mara, whose death at the hands of Burgess Darnell looms over her.

These ghosts are not just figurative representations of trauma but actual entities that continue to exert influence on the living, urging Oleana to confront her own past and seek justice. The ghosts that haunt her are symbolic of the way that unresolved pain and injustice can never truly be buried; instead, they continue to call out for recognition, resolution, and reckoning.

Genevieve’s connection to the past is similarly fraught, as she carries the weight of her abusive history, both in the form of the trauma she endured and the ghosts she communicates with. Her interaction with the ghost of Bigger, Mercer’s fallen friend, emphasizes how the past never fully lets go, shaping the characters’ present lives in ways they cannot control.

This theme of the past’s persistent influence reflects a larger commentary on how history—whether personal or collective—shapes the present, often in ways that the characters are forced to confront, even if they would prefer to forget.

Redemption and the Power of Connection

In the midst of trauma, violence, and suffering, The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree also explores the theme of redemption, which is often achieved through human connection, empathy, and support. Genevieve’s role in helping Mercer confront his PTSD and reconnect with his family is a powerful example of the redemptive potential of relationships.

Her compassion, bravery, and willingness to fight for others provide the emotional foundation upon which Mercer can rebuild his sense of self. Similarly, Oleana’s eventual act of revenge against her abuser, though chilling, is ultimately a form of reclaiming power and agency over her life.

It marks her transition from a victim to someone who can exercise control over her circumstances, and in doing so, she begins to heal. The theme of redemption is also embodied in the relationships between the characters, especially the way that they act as protectors for one another.

Genevieve’s protection of Jezzie, as well as her efforts to shield Mercer from further harm, are acts of both resistance and love that offer the possibility of redemption not only for the individuals involved but for the broader community they inhabit. Through these connections, the characters find healing, forgiveness, and a path forward, even in the face of deep-seated pain and loss.