Who Is Government Summary and Analysis

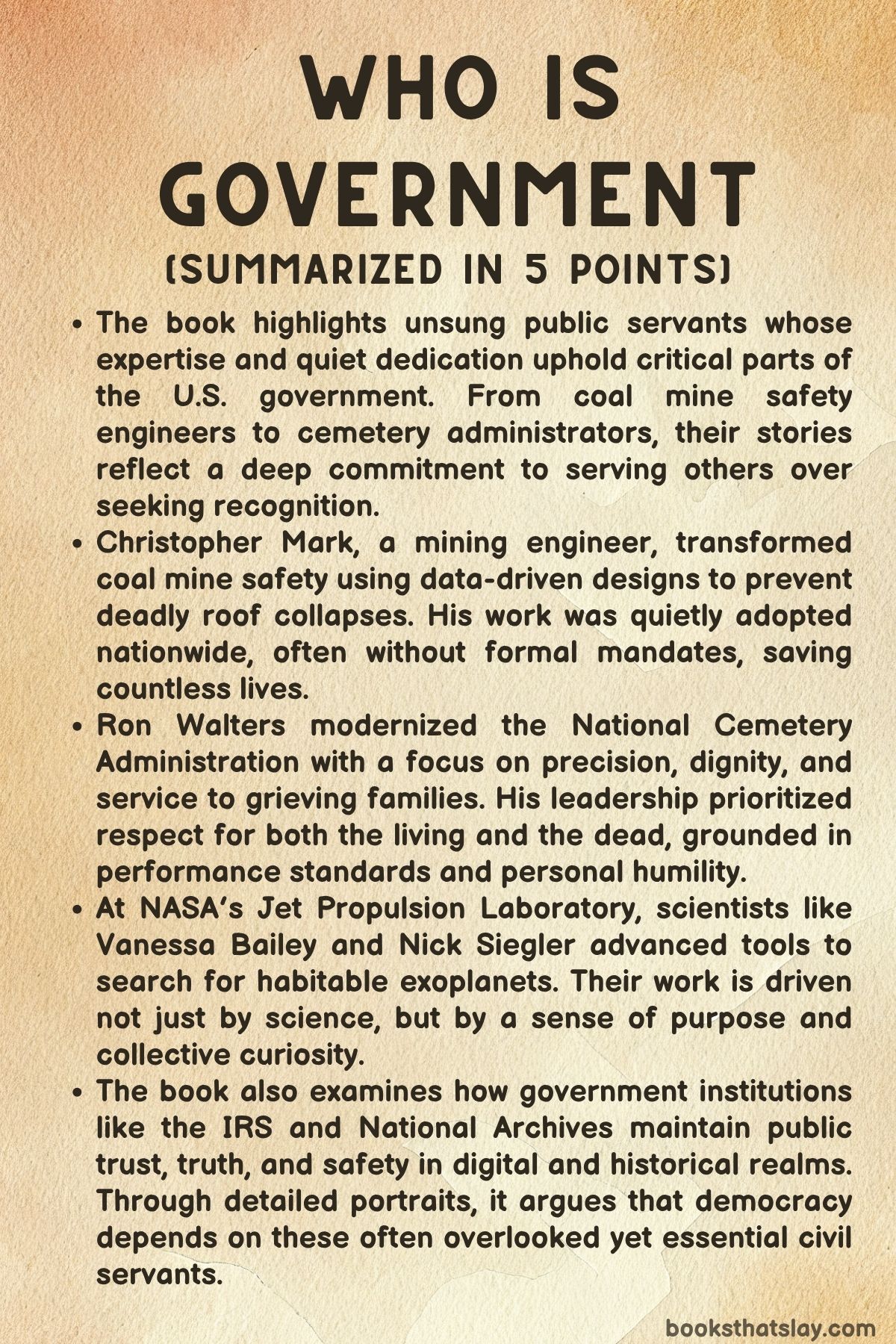

Who Is Government by Michael Lewis is an examination of the quiet, determined individuals who make the American federal government function—not in theory or law, but in daily practice. Far from the spectacle of elections or the spotlight of scandal, Lewis centers his narrative on civil servants who use intellect, perseverance, and moral clarity to safeguard public welfare, preserve institutional memory, and execute missions of justice, innovation, and compassion.

By chronicling their largely unheralded efforts, he presents a powerful case for why democracy relies not only on elected leaders, but on those who labor beyond the public eye—ordinary professionals whose commitment defines good governance in its most essential form.

Summary

Who Is Government by Michael Lewis is a collection of deeply human stories, each centered on a federal employee who exemplifies integrity, competence, and commitment in an era when public trust in government is waning. These profiles challenge the narrative of government inefficiency and bureaucracy by spotlighting civil servants whose work directly improves and protects American lives, often with little recognition.

One central figure in the book is Christopher Mark, a mining engineer who revolutionized coal mine safety. Initially inspired by his father, an engineering professor who studied the hidden structural strengths of Gothic cathedrals, Chris applied similar analytical rigor to one of the deadliest working environments in the U.S. —coal mines.

Despite being raised in a privileged, academic environment, Chris immersed himself in the working-class culture of West Virginia miners. His early radicalism evolved into a focus on technical solutions rather than ideological protest.

This shift led him to Penn State’s mining engineering program, where he embarked on a lifelong mission to understand and prevent roof collapses in longwall mines.

Chris’s work produced the first empirically supported system for designing mine support structures. He combined low-tech field techniques with advanced data modeling to create tools miners and engineers could actually use.

His methods were so effective that even without legal mandates, they were widely adopted across the industry. In 2016, the U.S. celebrated a year without a single roof collapse-related death—a milestone directly tied to Chris’s innovations.

The tragic 2007 Crandall Canyon mine collapse, which occurred after executives ignored his recommendations, solidified the importance of his contributions and pushed for new oversight policies.

Another chapter explores Ron Walters, a federal executive who reshaped the National Cemetery Administration. Walters focused on excellence through operational detail—like perfecting how grass is cut or how signs are displayed—to instill a deep sense of respect and dignity in national cemeteries.

He applied performance models from the private sector, set up training and apprenticeship programs (including for homeless veterans), and helped build call centers to streamline funeral services. Walters emphasized humility, refusing even to be buried in a veteran’s cemetery because he never served in the military.

His ethos of service extended to every level of the organization, nurturing a culture where employees saw every small act as a moral responsibility.

The narrative moves beyond Earth in the profiles of scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, particularly Vanessa Bailey and Nick Siegler. Bailey, who once captured a rare image of an exoplanet, contributes to the Roman Space Telescope’s mission to search for habitable worlds using a cutting-edge coronagraph.

Siegler, on the other hand, champions an ambitious, visually arresting alternative called the Starshade—a spaceborne device that could revolutionize the search for life. Both scientists reflect different approaches to discovery: Bailey, methodical and humble; Siegler, bold and visionary.

Their work underscores a quiet pursuit of knowledge that, while publicly underappreciated, could redefine humanity’s place in the cosmos.

The story of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) at the Bureau of Labor Statistics serves as a grounding contrast. Constructed with immense methodological complexity, the CPI translates economic experience into policy-informing data.

Despite its imperfections, it is crucial to understanding inflation and guiding government action. The growing skepticism toward such tools—fueled by populist distrust in institutions—signals a cultural shift that Lewis views with alarm.

Referencing Carl Sagan’s warnings about anti-scientific thinking, the narrative frames the CPI as a litmus test for society’s commitment to shared truths and rational governance.

In a more action-oriented segment, Lewis introduces Jarod Koopman, who leads the cybercrime division of the IRS Criminal Investigation unit. A martial arts black belt, Koopman oversees high-stakes operations that dismantle terrorist funding networks, rescue victims of child exploitation, and recover billions in stolen digital assets.

Despite the moral and strategic importance of his work, Koopman and his team are often demonized in political rhetoric. Nevertheless, his focus remains unwavering—defending public interest without seeking acclaim, his discipline grounded as much in personal ethics as in federal mission.

Pamela Wright’s story offers a different type of public service—one focused on access and memory. As chief innovation officer at the National Archives and Records Administration, Wright spearheaded digitization projects and interactive platforms like History Hub.

These tools democratize access to historical documents, allowing Americans to connect with their past from anywhere in the country. Raised far from Washington, Wright never saw power as local or exclusive.

Her commitment to transparency and technological engagement reflects a belief that government documents should not remain locked away, but should serve the people they were created for.

The book closes with a narrative that encapsulates the stakes of visibility and action. A little girl named Alaina is saved from a deadly brain infection thanks to a rarely used antibiotic called nitroxoline.

The treatment was identified and accelerated by Joe DeRisi, a researcher, and Heather Stone, a Food and Drug Administration official. Heather’s platform, CURE ID, was designed to crowdsource treatment breakthroughs for rare diseases, yet it remained underutilized—another example of life-saving tools hindered by bureaucratic neglect.

That the system almost failed Alaina serves as both a triumph and a warning: brilliance and potential abound in public service, but without systemic support and visibility, they can be tragically underleveraged.

Throughout Who Is Government, Lewis argues that these people—scientists, analysts, engineers, archivists—are the real infrastructure of democracy. Their labor is often dismissed or politicized, but their contributions are both measurable and morally resonant.

They hold up the literal and figurative foundations of the nation, and their continued efforts represent an act of faith in the idea that the government can and should serve its people—not through spectacle, but through competence, humility, and devotion.

Key People

Christopher Mark

Christopher Mark stands as one of the most technically gifted and ideologically principled characters in Who Is Government. Raised by a university engineering professor who decoded the mechanics of Gothic cathedrals, Chris inherited both intellectual rigor and a deep respect for invisible forces shaping the physical world.

His early attempts at labor activism—working as an undercover coal miner—were driven by his rejection of elitism and establishment politics. However, rather than becoming a political firebrand, Chris rechanneled his energy into engineering, realizing that saving lives would come not through rhetoric but through design.

His innovations in coal mine roof stability, particularly the empirically derived “stability factor” and practical classification tools, marked a transformative era in mine safety. Chris’s character is steeped in humility; he identifies more with miners than academics, despite his elite education and pioneering technical contributions.

His story is a portrait of integrity shaped by working-class empathy and scientific precision, one that underscores the book’s reverence for invisible yet critical public work.

Ron Walters

Ron Walters exemplifies the dignity of public service conducted with precision, empathy, and a strong managerial ethos. As acting undersecretary for memorial affairs at the National Cemetery Administration, Walters transformed what might be dismissed as bureaucratic maintenance into an emotionally charged mission of national reverence.

His reforms, rooted in performance management models like Baldrige and PDCA, were not about metrics for their own sake—they were about respect. From perfect mowing patterns to training programs for homeless veterans, Walters redefined burial services as an act of devotion.

He cultivated a culture where even minor gestures, like offering dry socks to grieving families, carried sacred meaning. Importantly, his leadership is defined by modesty and the refusal of personal acclaim; he declined burial in a veterans’ cemetery out of deference to those who served.

Walters’s story is not about ambition or innovation in the traditional sense, but about the quiet excellence of care that endures beyond public recognition.

Vanessa Bailey

Vanessa Bailey embodies the spirit of collaborative ambition and scientific humility in Who Is Government. As a key figure at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory working on the Roman Space Telescope, Bailey has dedicated her career to the search for life beyond Earth.

Her earlier imaging of a rare exoplanet and her ongoing work on the coronagraph highlight her technical brilliance, yet it is her philosophical orientation that stands out most. Bailey embraces “existential humility,” recognizing that humanity is but a fragment of the cosmos, and that the significance of discovering alien life lies not in novelty but in perspective.

She does not seek fame or recognition; instead, she focuses on the implications of her work for civilization’s collective imagination. In a world increasingly dominated by egos and individualism, Bailey’s ethos is a reminder that great science is often a communal, patient, and awe-filled endeavor.

Nick Siegler

Nick Siegler represents the audacious dreamer within the federal scientific complex. His advocacy for the Starshade—a massive deployable device designed to enable direct imaging of exoplanets—demonstrates his daring and charisma.

Unlike Bailey’s contemplative reserve, Siegler radiates energy and conviction, a trait rooted in his own improbable journey from factory worker to Harvard graduate to leading technologist at NASA. The Starshade, though still awaiting mission approval, symbolizes not just a technological feat but a personal one—a testament to perseverance, bold thinking, and belief in the value of government-led exploration.

Siegler’s presence in the narrative illustrates how individual imagination and public investment can intersect to yield visions of radical possibility.

Jarod Koopman

Jarod Koopman brings moral clarity and physical intensity to his role as head of the IRS Criminal Investigation cybercrime unit. A black belt in jiu-jitsu and a relentless investigator of digital wrongdoing, Koopman’s dual life mirrors his internal discipline and ethical resolve.

He chases down cybercriminals, rescues children from dark web predators, and dismantles terrorist financing pipelines—all while enduring public suspicion and political backlash. Koopman’s character reflects the inherent tensions of public service in the digital age: extraordinary stakes, often thankless labor, and a political environment that misconstrues caution for conspiracy.

Despite these challenges, he remains firmly rooted in purpose, driven by a commitment to public good rather than profit. His story is a modern-day parable of moral grit and technical mastery in service of justice.

Pamela Wright

Pamela Wright is a visionary within the National Archives and Records Administration who bridges historical stewardship with digital transformation. Raised far from Washington’s corridors of power, Wright has made it her life’s mission to ensure that America’s public records are accessible to everyone—not just the privileged few.

Her leadership in launching citizen archivist programs and digital platforms like History Hub reflects a profound belief in participatory democracy. Wright’s innovations have not only made federal archives more navigable but have also empowered ordinary citizens to uncover their personal and collective histories.

She is the embodiment of inclusive government—one that uses technology not to distance but to connect, not to obfuscate but to illuminate. Her character reminds readers that stewardship of history is not about preservation alone, but about democratization.

Olivia

Olivia, a young paralegal in the DOJ’s Antitrust Division, represents a new generation of idealistic public servants caught between aspiration and economic reality. Her deep engagement in antitrust work—uncovering monopolistic behavior in industries ranging from publishing to sports—demonstrates her intellectual seriousness and civic commitment.

Yet her personal narrative, shaped by the looming burden of student debt, mirrors the structural hurdles that often discourage young people from entering or remaining in public service. Olivia is a compelling symbol of both hope and fragility—she believes in fairness, equity, and the power of government to protect consumers, but she is also uncertain whether she can afford to stay in the fight.

Her story is not just about youth in government; it is about a country that must decide whether it values service enough to sustain those who choose it.

Max Stier

Max Stier serves as a philosophical anchor in Who Is Government, championing the vital yet often neglected domain of federal human capital. As founder of the Partnership for Public Service and creator of initiatives like the Sammies, Stier has made it his mission to reinvigorate faith in government through people.

His efforts to recruit young, idealistic workers like Olivia signal a strategic understanding of demographics: without a generational renewal, government itself may falter. Yet Stier is not a blind optimist; he understands the systemic challenges—bureaucracy, political vilification, financial disincentives—that erode faith in public institutions.

His character blends urgency with pragmatism, making him one of the book’s most articulate defenders of democratic infrastructure. Through Max, the reader confronts a core truth: institutions are only as strong as those who inhabit them.

Heather Stone

Heather Stone, an FDA analyst, represents the unsung ingenuity that lies buried in the federal bureaucracy. Her role in rescuing a child from a deadly amoeba using nitroxoline—an obscure antibiotic—exemplifies the transformative potential of resourcefulness within the system.

But Heather’s story is also one of frustration. Despite creating CURE ID, a groundbreaking tool for surfacing off-label drug successes, she struggles to gain institutional traction.

Her persistence in the face of neglect underscores the costs of invisibility in government work: breakthroughs may be made, but without adequate support or recognition, they risk withering. Heather’s character captures the moral complexity of bureaucratic labor: devotion despite obstruction, brilliance shrouded in red tape, and the quiet heroism of refusing to give up when lives are on the line.

Alaina

Alaina, the little girl who survives a fatal brain infection thanks to Heather Stone and Joe DeRisi’s work, appears only briefly but serves as an emotional fulcrum for the narrative. Her recovery is not merely a personal miracle—it is a symbol of what is at stake in public health, research, and federal responsiveness.

Though not a character with agency, her presence amplifies the human consequences of bureaucratic success or failure. Through Alaina, the abstract becomes tangible: lives are saved not by institutions alone, but by people within them willing to defy inertia.

analysis of Themes

Civic Duty as a Form of Quiet Heroism

Across the stories chronicled in Who Is Government, civic duty emerges not as a ceremonial or theoretical notion but as an ethic deeply rooted in personal humility, endurance, and often anonymity. Civil servants like Christopher Mark, Ron Walters, and Pamela Wright do not view their roles as pathways to glory or recognition but as essential acts of responsibility toward the larger social fabric.

Their choices—to perfect burial procedures, engineer coal mine safety systems, or democratize access to archival records—represent a profound commitment to the idea that democracy is upheld not just by votes or elected officials, but by the unseen labor of those who work behind the scenes. These individuals embody a version of heroism that is neither cinematic nor brash.

They willingly immerse themselves in tasks that require painstaking attention to detail, institutional navigation, and moral clarity. For Mark, that meant translating empirical data into engineering practices that saved lives, even without the support of Congressional mandates.

For Walters, it meant holding national cemeteries to sacred standards of care and comfort. The book insists that these are not isolated cases but representative of a vast, underacknowledged workforce whose value is often ignored or denigrated.

This theme challenges the prevailing cultural caricature of the bureaucrat as lazy or obstructive and instead offers a compelling image of public servants as stewards of the collective good, carrying out their roles with grace under the radar.

The Tension Between Institutional Inertia and Innovation

A central thread in Who Is Government is the friction between visionary individuals and the slow-moving institutions in which they operate. While the book is filled with stories of transformation—technological, procedural, or philosophical—these changes rarely come easily.

Christopher Mark’s contributions to mine safety, for example, were not mandated by law but adopted because their outcomes were too compelling to ignore. Similarly, Heather Stone’s development of CURE ID at the FDA was envisioned as a way to democratize drug efficacy data, yet the platform struggled to gain traction within a system that often privileges procedural orthodoxy over urgent innovation.

Institutional inertia appears as both a protective structure and a barrier: it preserves processes and rules intended to ensure fairness and consistency, but it can also prevent timely action, especially in matters of life and death. This theme becomes especially potent when systemic sluggishness has tangible costs—as in the near-missed opportunity to save a child from a rare disease or in the deadly disregard of mining safety protocols.

Yet innovation is often forced through by individuals who understand not only science or management but also institutional psychology. Ron Walters reshaped the NCA by adapting business-world metrics and investing in staff culture; Pamela Wright used digital tools to breach the distance between citizens and their histories.

These agents of change are successful not because they rebel against the system entirely, but because they learn to work within and around it, changing it from the inside out.

The Moral and Political Value of Expertise

In an era of growing distrust toward elites and institutions, Who Is Government makes a strong case for the moral necessity of expertise. The book does not romanticize credentials or academic prestige—in fact, several of its most celebrated figures actively resist those associations.

But it does insist that technical mastery, domain-specific knowledge, and procedural rigor are not only useful but foundational to a functioning democracy. Whether it’s the meticulous calibration of the Consumer Price Index by the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the high-stakes engineering behind NASA’s coronagraphs and starshades, the work described requires not just intelligence but a deep, sustained application of specialized knowledge.

These civil servants do not simply “follow the science”; they build it, maintain it, and explain it in the service of public good. Their commitment to truth, precision, and accountability pushes back against a cultural moment increasingly dominated by opinion, disinformation, and ideological certainty.

The book presents expertise not as an elite monopoly but as a public resource, one that depends on open access, peer validation, and institutional continuity. The stakes are made clear: when expertise is discredited or ignored—as in the Crandall Canyon mine disaster or the underfunding of disease research—the consequences are fatal.

Thus, the book makes a vital philosophical argument: democratic societies must safeguard and value technical truth, not only as a matter of efficiency but as a matter of justice.

Service, Recognition, and the Politics of Visibility

A recurring motif in Who Is Government is the paradox of visibility: those who sustain the very systems that uphold national ideals often remain in obscurity. The Sammies—the awards initiated to spotlight exemplary federal service—were created precisely to counter this tendency.

Yet the stories of Walters, Mark, Wright, and others reveal how uncomfortable many of these public servants are with personal acclaim. Walters, for instance, refuses to be buried in a national cemetery because he never served in the military, despite revolutionizing how those cemeteries function.

Christopher Mark’s humility is rooted in his allegiance to working people, not to professional accolades. The book interrogates why so many essential contributors remain unseen and unappreciated, even as their work touches millions.

It also questions a media and political culture that often reduces the concept of government to slogans, headlines, and scandals, ignoring the quieter processes of maintenance, innovation, and care. The absence of recognition is not merely symbolic; it has material consequences.

It leads to underfunding, burnout, and a generational talent gap—highlighted in the narrative about Olivia and her student debt dilemma. By revealing these blind spots, the book argues for a cultural and institutional shift toward recognizing the full scope of what government is and who makes it work.

Visibility, in this context, becomes not a matter of ego but of justice and democratic sustainability.

Government as a Site of Moral Choice and Institutional Resilience

Beyond its individual portraits, Who Is Government proposes that federal institutions are not faceless monoliths but dynamic systems shaped by human choices. The IRS cybercrime division under Jarod Koopman is not simply a tax enforcement body; it becomes a site where children are saved, terrorist networks are disrupted, and billion-dollar crimes are tracked.

The National Archives is not just a repository; under Pamela Wright, it becomes a tool for social memory and civic engagement. These transformations suggest that even within rule-bound structures, moral clarity and institutional evolution are possible.

The civil servants portrayed in the book are not passive executors of policy but moral agents who grapple with decisions that affect lives, rights, and futures. This framing matters profoundly in an age of democratic erosion.

When trust in institutions is low, it becomes easy to abandon them. But the book argues that the solution lies not in dismantling the state but in reforming it through dedicated stewardship.

These federal workers model what that stewardship looks like—measured, principled, and people-centered. Institutional resilience, then, is not just about budget continuity or legal frameworks; it’s about culture, ethics, and the presence of people who care deeply about outcomes.

By embedding moral choice within institutional life, the book resists cynicism and offers a hopeful, if complex, vision of government as both structure and soul.