Woodworking by Emily St. James Summary, Characters and Themes

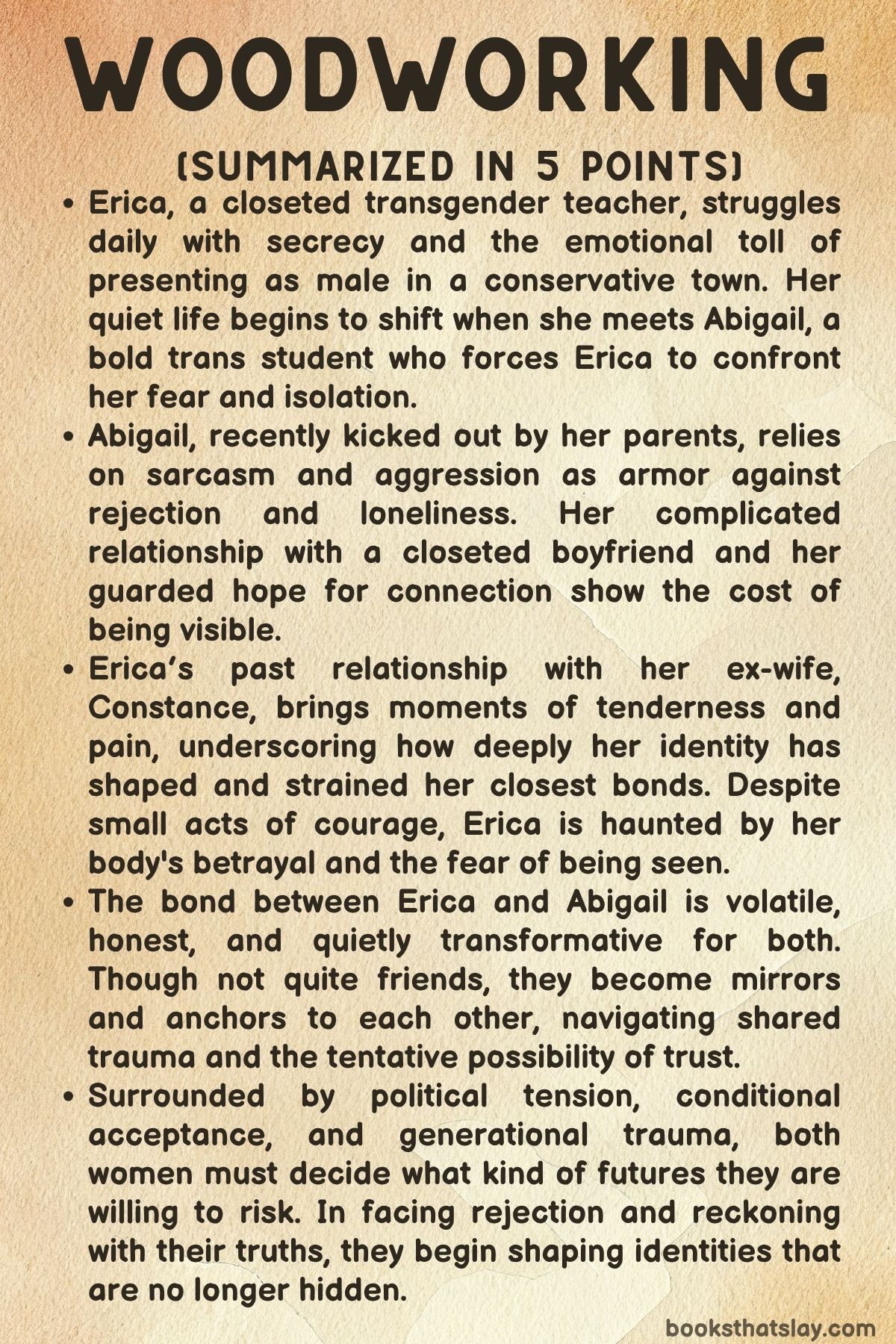

Woodworking by Emily St. James is a deeply reflective and emotionally rich novel that explores the quiet, brutal, and transformative realities of being transgender in a conservative American town.

Through the intertwined lives of Erica, a middle-aged teacher quietly transitioning in secrecy, and Abigail, a sharp-tongued trans teenager navigating rejection and resistance, the novel explores themes of identity, visibility, connection, and survival. Set in Mitchell, South Dakota, it traces one month of tentative friendship, hard truths, and small victories in the face of overwhelming hostility. The story is not about spectacular change but about the emotional labor of becoming—slow, uneven, but deeply human.

Summary

Erica, a high school teacher in her forties, lives behind a constructed identity. She is a closeted transgender woman who continues to go by “Mr. Skyberg” at work and maintains the appearance of her old life to avoid scrutiny. Her transition is internal, guarded, and full of fear.

She polices her mannerisms, her speech, and even the way she walks. The isolation and shame weigh heavily, but something changes when she learns that one of her students—Abigail, an openly trans teen—used incendiary language in class.

Erica switches detention duties with a colleague to confront, and perhaps connect with, the only other trans woman she knows in town.

Abigail is bold, angry, and armed with sharp sarcasm. Kicked out by her parents and living with her older sister Jennifer, she has learned to speak first and hardest to protect herself.

Her relationship with Caleb, a closeted boy from a prominent local family, is riddled with secrecy and internalized hate. Her sense of safety is fractured, and she carries the pain of constant misgendering and rejection.

Despite her guarded exterior, Abigail feels an unexpected affinity with Erica. Their first interactions are bristling with tension, but a shared understanding begins to form—fragile but real.

Erica, meanwhile, battles regret and longing in her relationship with Constance, her ex-wife. The marriage fell apart not in conflict but in silence—Erica could never share her true self.

Constance, now pregnant with her new partner John, offers moments of kindness that Erica clings to. But Erica is also destabilized by John’s easy masculinity and what it reminds her she is not.

She attends a support group for trans people, starts daily walks, and helps with local political campaigning, tentatively exploring what it means to be seen.

Abigail and Erica’s relationship grows into something ambiguous but vital. Abigail insists they are not friends but cannot help being drawn to Erica’s awkward vulnerability.

She challenges Erica to be braver, to stop hiding, to take up space as a trans woman. In return, Erica offers quiet presence, listening ears, and perhaps a kind of maternal understanding that Abigail never received.

They clash often—both wounded, both projecting—but neither walks away.

Abigail’s world remains volatile. Her sister Jennifer tries to gain legal guardianship, but Abigail feels blindsided and betrayed by the process.

She escapes to Caleb’s house only to find that his family’s tolerance is conditional. Brooke, Caleb’s mother, supports her son but dismisses trans people who don’t meet her standards of respectability.

The sanctuary Abigail hoped for turns out to be another form of rejection. Meanwhile, Erica grapples with dysphoria so intense it ruins a night of rekindled intimacy with Constance.

The physical reality of her body becomes too painful to bear, and Erica spirals back into hiding, reverting to the name “Asdf” and adopting masculine behaviors to numb herself.

This retreat devastates Abigail. She lashes out, calling Erica a coward and abandoning their fragile alliance.

Yet even in her anger, she cannot fully detach. When Erica’s mental state crumbles under the pressure of rejection and invisibility, Abigail returns—not with sentiment, but with sharp honesty and reluctant care.

The narrative intensifies when Abigail’s parents reappear and try to force her home. In a tense confrontation, allies step forward: Megan, Abigail’s classmate; Constance; Caleb; and Erica.

Megan physically intervenes, enabling Abigail to escape. They flee to Brooke’s house, which surprisingly becomes a site of deeper understanding.

Brooke admits to Abigail that she is also trans, revealing a hidden lineage of queer survival that reframes their connection. Later, Abigail visits Brooke’s mother, Danielle, extending the theme of generational resilience.

Political tensions in town mirror these personal reckonings. At a state senate debate, liberal candidate Helen, who knows both Erica and Abigail, speaks out against the religious right’s targeting of trans people.

She shares her own experience with abortion and uses it to highlight the dangers of moral hypocrisy. Though she knows she will lose the race, her declaration is an act of public truth-telling that ripples through the lives of those around her.

Erica, having been quietly ousted from her teaching position under false pretenses, makes a decisive move. She comes out to Helen, hoping to both defend herself and claim her identity.

The act of telling the truth becomes a personal victory. Helen acknowledges the risk and affirms Erica’s courage, even as she expresses concern for Abigail’s well-being.

Abigail, reeling from the discovery of Caleb’s college essay—which praises her while exposing her deadname—runs again. This time, she is found by Brooke, who sees and affirms her without condition.

Their shared identity becomes a bridge, not just of sympathy but of recognition. Abigail begins to see her future not only in survival but in purpose.

She imagines becoming a therapist, someone who can help others navigate what she has endured.

The novel ends with Erica preparing to move to Madison, Wisconsin, to begin hormone therapy and attend graduate school. Abigail remains in town, working with a support group and defending younger queer kids, including a trans girl named Zoe who’s being mocked while handing out political flyers.

Abigail steps in—not to save Zoe, but to stand beside her.

In their final moments, both women are still broken in places, still struggling. But they are no longer alone.

Their stories aren’t tied up neatly. There are no grand reconciliations or sweeping social victories.

What they have instead is something quieter but more enduring: a shared knowledge of what it means to be seen, and the strength to keep moving forward. In that fragile connection, Woodworking finds its quiet power.

Characters

Erica

Erica is the emotional heart of Woodworking, a middle-aged transgender woman who has spent much of her life hiding from herself and the world around her. Living under the guise of “Mr. Skyberg,” Erica is a high school teacher in a conservative South Dakota town, navigating a suffocating world of performative masculinity and internalized transphobia. Her every action is shaped by fear—fear of exposure, judgment, and most painfully, of being truly seen.

She begins her journey in deep denial, terrified of the implications of her gender identity. Even as she dares to paint her nails or attend support groups, she does so furtively, always on the edge of retreat.

Erica’s dysphoria is not just physical but existential—she struggles not only with her appearance but with the notion of being worthy of love, visibility, or permanence.

Her relationship with Abigail becomes a mirror and a lifeline. Through Abigail’s unapologetic presence, Erica glimpses the life she might have lived had she embraced her truth earlier.

But this connection also terrifies her. She oscillates between tenderness and withdrawal, kindness and cowardice.

Her relationship with her ex-wife Constance—who now offers her loving, if complicated, support—adds another layer of emotional complexity. Constance affirms Erica’s identity in word and touch, but Erica’s dysphoria makes intimacy unbearable, creating a tragic disconnect between love and embodiment.

Eventually, Erica’s journey moves toward courage. After years of shame, she begins to emerge.

She comes out to her colleagues, stands by Abigail during moments of crisis, and chooses to begin hormone therapy. Her declaration—“Erica isn’t something I can turn off.

Erica is me”—represents a hard-earned triumph, one that is quiet but profound. While she loses her job and remains haunted by the compromises of the past, Erica reclaims her identity with trembling honesty.

She is not a perfect heroine, but her growth lies in finally choosing to live as herself, no longer through fantasy or erasure but through reality.

Abigail

Abigail is the fiery, uncompromising soul of Woodworking, a trans teenager whose rage and sarcasm mask a heart that longs for safety, visibility, and love. Kicked out by her parents for coming out, she lives with her sister Jennifer, moving through the world with armor made of sharp wit and emotional barbs.

Abigail is acutely aware of how the world sees her—not as a girl, but as a spectacle or abomination. Her survival depends on controlling that gaze, pushing people away before they can hurt her.

But beneath her abrasiveness lies a deep well of pain, humor, and longing.

Her relationship with Caleb, her closeted boyfriend, encapsulates her emotional contradictions. She wants love, but she wants it without caveats—without being someone’s secret or shame.

Caleb’s inability to fully accept her forces her into moments of bitter clarity, and when she discovers he used her deadname in a college essay, it becomes a shattering betrayal. Her subsequent retreat is not just an act of fear but of self-preservation—a refusal to be defined on anyone else’s terms.

Abigail’s bond with Erica is filled with ambivalence. She pushes Erica to be braver while simultaneously rejecting Erica’s dependence.

She calls out Erica’s cowardice but also recognizes the unbearable weight of trans adulthood. At times, she sees Erica as a mentor, at others as a warning.

Through their fraught connection, Abigail begins to understand the contours of her own future—not as someone who must always fight, but as someone who might, eventually, be allowed to rest. Her activism, her reluctant friendship with Megan, and her final act of reaching out to a younger trans girl all show her growth.

Abigail remains angry, but her anger becomes tempered with compassion. She becomes not only a survivor but a source of hope for others, even as she continues to heal.

Constance

Constance, Erica’s ex-wife, is a figure of immense grace, contradiction, and emotional maturity. Her marriage with Erica dissolved under the weight of unspoken truths, not from a lack of love but from an inability to communicate.

Now in a relationship with John and expecting a child, Constance remains a quiet but powerful presence in Erica’s life. She represents a bridge between Erica’s past and her possible future—a woman who has seen the worst of Erica’s pain and yet still offers love and support.

Her willingness to accept Erica as she is, even after so many years of secrecy, is remarkable. She defends her in public, stands by her during professional crises, and even attempts to rekindle a physical relationship—not as nostalgia, but as affirmation.

However, the intimacy they try to share reveals a deeper wound in Erica, who remains locked in dysphoria and self-doubt. Constance’s patience during this moment of physical failure is not humiliating but deeply humanizing.

She remains firm but compassionate, understanding that love alone cannot heal someone who has not yet chosen to live fully.

Constance is neither saint nor savior. She sets boundaries, stands up to her current partner’s casual transphobia, and demands honesty.

Yet she never uses her pain as leverage. Instead, she serves as a kind of emotional anchor for Erica, helping her move forward without demanding reparation for the past.

Her presence is proof that relationships can evolve, that love can change shape without disappearing, and that acceptance is not a singular act but an ongoing choice.

Caleb

Caleb is a deeply conflicted character in Woodworking, embodying the toxic effects of internalized homophobia and performative masculinity. As Abigail’s boyfriend, he exists in a painful state of contradiction—deeply attracted to her yet unwilling to publicly affirm her.

His shame poisons their relationship, forcing Abigail to exist as his secret rather than his equal. Though he expresses affection, he fails to protect her or even stand up for her when it counts, revealing the limits of his love.

Caleb’s betrayal—using Abigail’s deadname in a college essay—exposes the depth of his misunderstanding. Though he believes he is honoring her, he violates the very core of her identity.

This moment becomes a turning point not only for Abigail but for Caleb himself. Confronted with the consequences of his cowardice, Caleb begins a slow unraveling.

His relationship with his mother, Brooke, mirrors this arc. When she finally comes out as trans, Caleb is forced to reckon with the people he loves being braver than he can be.

Despite his failures, Caleb is not written off entirely. He plays a crucial role in defending Abigail from her parents, physically placing himself between her and danger.

His actions in this moment suggest the beginnings of redemption—not absolution, but recognition. Caleb’s character offers a sobering reminder of how good intentions can still cause harm, and how love without courage is not enough.

Brooke

Brooke, Caleb’s mother, undergoes one of the most profound transformations in Woodworking. At first, she appears as a liberal, well-meaning woman—kind to Abigail, dismissive of outright bigotry, and active in community affairs.

But her kindness is conditional. She supports Abigail only within limits, draws lines around “acceptable” trans identities, and mocks Florence, an older, visibly trans woman, as a “man in costume.”

Her tolerance is steeped in respectability politics.

However, Brooke’s own secret—that she too is a closeted trans woman—adds stunning complexity to her arc. Her internalized transphobia is revealed not as cruelty but as fear—a survival strategy that required denying others to stay hidden herself.

Her late-night confession to Caleb, and her letter to her estranged sister, mark a seismic shift. She begins to reframe her life not around safety but around truth.

In the story’s final chapters, she becomes a fierce protector of Abigail, offering her home as sanctuary and standing up to Abigail’s parents. This act is not merely protective but redemptive—an act of solidarity born from long-delayed self-acceptance.

Brooke becomes a model of what delayed liberation looks like: imperfect, painful, but deeply necessary. Her arc reminds us that identity isn’t fixed by age and that coming out is not a singular event but a continuous act of courage.

Megan

Megan is a minor yet resonant character whose presence offers a counterpoint to Abigail’s guardedness. A cheerful, civic-minded classmate, Megan initially appears shallow—an eager ally looking for moral credit.

But as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that her motivations stem from genuine loneliness and a desire for connection. Abigail’s initial cynicism gives way to reluctant respect as she realizes that Megan, too, lives on the margins of popularity and acceptance.

Megan’s most significant moment comes during Abigail’s confrontation with her parents, where she physically intervenes to protect her. This act of bravery cements her as more than a well-meaning liberal; she becomes a true ally.

Through Megan, the novel explores the possibility of friendship forged not through ideology but through shared vulnerability and mutual defense. Her growth, like many others in the book, comes through witnessing suffering and choosing to act.

Megan is proof that compassion, when combined with courage, can become transformative—not only for those we protect but for ourselves. Her friendship with Abigail may never be uncomplicated, but it offers a rare and hopeful vision of cross-experience solidarity in a world divided by fear.

Themes

Trans Identity and Conditional Acceptance

The narrative in Woodworking explores how trans identities are persistently subjected to external validation and conditional acceptance, even from those who profess support. Erica’s journey as a closeted middle-aged transgender woman is shaped by her fear of being seen, her past erasures, and the reactions of others—particularly her ex-wife Constance and her conservative South Dakota community.

Every act of self-assertion she takes, from wearing pink nail polish to speaking her truth aloud, is met with scrutiny or subtle forms of dismissal. Abigail, too, faces similar pressures.

Her parents’ offer to allow her to be herself “at school” while remaining “their son” at home epitomizes this selective tolerance. Even allies like Brooke, who initially perform liberal acceptance, reinforce damaging hierarchies—drawing lines between “respectable” and “inappropriate” trans people.

This theme underscores how external validation remains a gatekeeper to safety and recognition, creating a landscape where being fully oneself is not just brave, but dangerous. The book insists that survival for trans individuals is not contingent on how palatable they appear to others, but on rejecting these terms of conditional love.

Erica, Abigail, and even Brooke confront these terms, and each character’s choice to be visibly trans—despite the costs—becomes a reclamation of self that doesn’t ask for permission.

Isolation and the Fragility of Connection

Loneliness permeates both Erica and Abigail’s lives, but it is not just the absence of company—it is the ache of being unseen. Erica hides behind “Mr.

Skyberg,” behind Asdf, behind coded conversations and anxious body language. She has no one to confide in until Abigail appears, not as a savior, but as someone who simply sees her.

Abigail is surrounded by people—classmates, Caleb, Jennifer—but her guarded sarcasm, her refusal to be pitied, makes intimacy impossible. She trusts no one completely.

Even Megan, whose interest is genuine, is met with skepticism. These twin emotional islands—Erica and Abigail—begin to form a fragile bridge between them.

But the bridge constantly threatens collapse under the weight of miscommunications, unmet needs, and projection. Their alliance is neither a clean mentorship nor a surrogate mother-daughter relationship.

It is uncertain and unbalanced, defined by both deep need and deep fear. This fragility is most evident in moments of disappearance and crisis: Erica losing Abigail after her parents’ confrontation; Abigail feeling betrayed when Caleb outs her deadname.

The moments they do connect—through whispered confessions, a shared car ride, a rescue—are tender and tentative. These flickers of connection do not resolve their loneliness, but they disrupt it.

They prove that even fragile, impermanent ties can carry enough weight to keep someone from drifting too far from themselves.

Visibility and the Politics of Being Seen

The act of being seen—not just recognized, but understood and accepted—is central to both Erica and Abigail’s arcs. Erica counts glances, tracks who notices her femininity, and constantly fears the gaze of others.

Her dysphoria is mapped not just onto her own body, but onto how her community perceives her. When she is escorted out of the school building, the event is staged under the pretense of a family emergency—an attempt to erase the spectacle of her identity.

Abigail, too, battles with the meaning of visibility. Her relationship with Caleb, a closeted gay boy, forces her to live in the shadows.

His college essay, though filled with admiration, becomes a violent breach of privacy because it exposes her without consent. Being seen, in this world, is both salvation and threat.

Brooke’s journey provides a powerful echo of this dilemma. As a closeted trans woman in a position of social privilege, she has the luxury of remaining invisible—but at the cost of her integrity.

Her eventual decision to come out to her son, and later to her sister, shows how visibility is also a choice to live fully, even if it means losing status or control. The book ultimately argues that visibility is not a performance but an act of resistance, a way to say “I exist” in spaces that demand silence.

Intergenerational Solidarity and Recognition

Throughout Woodworking, the connection between Erica and Abigail functions not as a clean mentorship but as a messy, urgent form of intergenerational solidarity. Erica sees a younger version of herself in Abigail—more audacious, more angry, more alive.

Abigail sees in Erica the haunting possibility of what might become of her if she loses her fire. Their relationship is transactional at times, fraught with boundaries and irritation, but also deeply nourishing.

Abigail calls Erica her “trans mom,” and while she mocks this title, it is also a declaration of trust. Erica, though hesitant and self-effacing, begins to realize that her role in Abigail’s life carries weight.

She cannot save Abigail, nor should she, but her presence offers a form of affirmation that goes beyond advice or caretaking. This solidarity is echoed in Brooke and Abigail’s later interactions.

Brooke, finally honest about her identity, steps in as a protective figure, housing Abigail and creating space for her to heal. Even the support group, and characters like Florence and Zoe, expand this web of recognition—each person holding up a mirror to another.

These bonds, while imperfect, create a chain of survival that extends across age and experience. The narrative makes clear that trans liberation is not a solo endeavor—it is made possible when one person’s truth makes space for another’s.

Bodily Disassociation and Embodiment

The relationship between body and identity is rendered with painful honesty in the experiences of both main characters, particularly Erica. Her relationship with her body is marked by distrust and alienation.

Physical intimacy becomes almost impossible, not because of lack of desire, but because of how dysphoria distorts touch and closeness. When Constance tries to rekindle intimacy, Erica flinches—not from her, but from the skin she lives in.

Her efforts at transition are halting: nail polish, new names, hormonal plans. Each step forward is undone by shame, fear, or the casual cruelty of others.

Abigail, in contrast, clings to her body as a site of truth. She fights for the right to name herself, dress herself, and inhabit her body without apology.

Yet she too experiences disassociation, especially after trauma, when her narration distances itself from her physical presence. These parallel journeys reveal that embodiment is not a fixed destination but a fluctuating state of negotiation.

Brooke, again, acts as a pivot point. Her polished exterior masks decades of bodily denial.

Only in private letters and midnight confessions does she reclaim her physical truth. Woodworking does not romanticize embodiment.

It recognizes that for trans people, being in one’s body can be both a liberation and a battlefield. But it insists that even fractured relationships with the body hold the possibility of peace—not through transformation alone, but through acceptance.

Resistance and the Ethics of Care

Abigail’s activism and Erica’s quiet resistance present two modes of survival in hostile territory. Abigail’s methods are confrontational—calling out adults, staging interventions, physically resisting harm.

Her confrontation with her father, and her participation in student democracy movements, underscore her refusal to be erased. Erica, meanwhile, resists through persistence: attending support groups, standing up to Hank, telling the truth even when it costs her job.

Both forms of resistance are acts of care—not just for themselves but for others. Abigail defends Megan from performative liberalism and protects Zoe from bullying.

Erica sacrifices her safety to validate Abigail’s existence. Brooke’s late-in-life awakening brings yet another dimension: the resistance of choosing truth after years of hiding, the care of creating a safer home for Abigail, and the humility to apologize for past harm.

This ethic of care is not always gentle—it is often blunt, angry, and desperate—but it is always rooted in love. The book challenges the idea that resistance must be loud to matter.

It honors the quiet bravery of enduring, of reaching out, of choosing honesty even when the world demands retreat. Through these characters, Woodworking insists that care is a political act, especially in communities where survival itself is not guaranteed.