Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng Summary, Characters and Themes

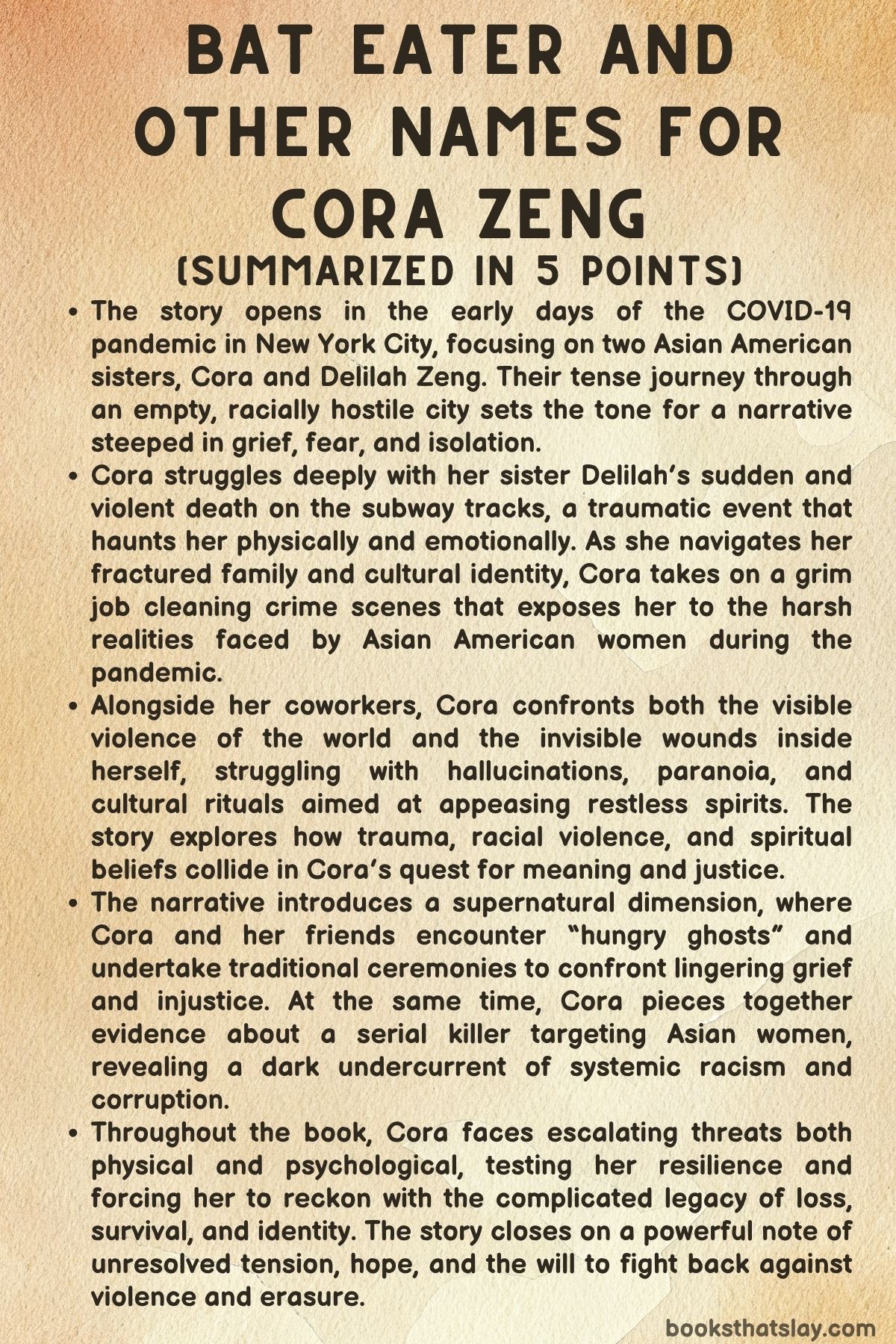

Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng by Kylie Lee Baker is a dark, intense narrative set against the backdrop of the early COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. It follows Cora Zeng, a young Asian American woman haunted by the violent death of her sister, Delilah, amidst rising racial tensions and a wave of brutal crimes targeting Asian women.

The story explores themes of grief, trauma, cultural identity, and systemic racism through Cora’s experience working as a crime scene cleaner, navigating fractured family ties, and confronting supernatural hauntings linked to the losses she endures. The book presents a raw and unflinching portrait of survival in a hostile, uncertain world.

Summary

The story opens in April 2020 at an East Broadway subway station in New York City, a grim symbol of decay and fear during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. The city is deserted, gripped by panic and racial scapegoating directed at Asian communities.

Sisters Cora and Delilah Zeng, two young Asian American women, face this hostile reality firsthand. Their attempt to acquire scarce supplies like toilet paper takes them through eerie, empty streets where anti-Asian racism manifests in subtle and overt ways — even something as simple as securing an Uber ride proves impossible.

As they return to the subway platform, Cora senses something ominous, while Delilah remains hopeful.

Delilah is portrayed as fragile and ethereal, her dreams of modeling and lightness contrasting sharply with Cora’s grounded and troubled existence. Cora’s feelings of invisibility and resentment toward her sister’s seemingly effortless presence create a fraught internal dynamic.

This tension culminates in a devastating moment when Delilah is violently shoved onto the subway tracks by a white man and killed by an oncoming train. Cora’s desperate screams are swallowed by the empty station, leaving her isolated in her grief.

Four months later, Cora works as a crime scene cleaner alongside her coworkers Harvey and Yifei. Their job places them in direct contact with the violent deaths piling up in the city, particularly among Asian American women who are targets of racialized violence.

The grim work of cleaning blood, brains, and death’s aftermath is both alienating and oddly grounding for Cora, who lives in a sanitized Chinatown apartment, isolating herself from a world she cannot trust. The appearance of bats trapped in vents at a victim’s apartment becomes a chilling metaphor for the origins of the pandemic and the stigma surrounding Asian people.

Cora’s personal life is fractured. Her father has returned to China, her mother is caught in a cult, and her Auntie Zeng offers a mixture of traditional mourning rituals that clash with Cora’s skepticism.

Religious tensions run high with Auntie Lois, a Christian relative who supports Cora financially but pushes spiritual conformity she cannot embrace. Cora’s attempts to find refuge in faith fail, reflecting her deep cultural and emotional alienation.

The story also explores the unresolved trauma of Delilah’s death. Cora wrestles with bitterness and the absence of justice, her grief complicated by the violent and racially charged context surrounding her sister’s murder.

Her relationships with Harvey and Yifei—marked by shared trauma and dark humor—highlight different modes of coping with violence and loss. Harvey escapes into video games, Yifei maintains a pragmatic toughness, and Cora lives with haunted sensitivity.

Cora’s mental and physical health deteriorate as she experiences mysterious dark spots in her vision, which she fears could be a serious eye problem but which doctors attribute to psychological causes. The hallucinations, anxiety, and creeping sense of darkness invade her home life.

Yifei introduces Cora to the concept of “hungry ghosts,” spirits of the neglected dead who suffer eternal hunger, blurring the line between supernatural haunting and psychological trauma.

The narrative deepens its spiritual and supernatural themes as Cora encounters ghostly presences linked to her sister and the broader violence in their community. An encounter with Father Thomas in a cathedral crypt amplifies her feelings of isolation and the fear that others harbor toward her.

Racial violence explodes when a brick shatters a window at a Chinese restaurant where Cora and her friends are dining, forcing them to flee and underscoring the ever-present threat surrounding them.

Cora’s apartment becomes a site of terrifying hauntings, including a ghostly woman who devours her coffee table, symbolizing the insatiable hunger of grief and guilt that no ritual can satisfy. Cora’s attempt to offer symbolic food to this entity reveals her struggle to reconcile loss and cultural expectations of mourning.

Meanwhile, Yifei channels her anger into activism, determined to expose a serial killer targeting Asian women in Chinatown—a killer whose modus operandi and the racial slur “bat eater” connect the physical violence to deeper racial hatred.

The story follows Cora, Yifei, and Harvey as they search subway tunnels and dark city spaces for traces of Delilah’s remains and clues to the killer’s identity. Their quest is fraught with danger and psychological torment.

They discover physical evidence like bloodstains and bone fragments, but much has been erased by time, decay, and the cruelty of the city’s indifference.

Supernatural interventions and traditional rituals—ghost feasts, burning joss paper, scattering rice—offer brief hope for releasing restless spirits, but the haunted city resists closure. A USB drive containing shredded police files reveals a cover-up of the serial killings, implicating city officials who suppressed investigations to avoid political fallout.

The killer is revealed not as a lone individual but as part of a wider racist movement responsible for systematic violence against Asian women.

The narrative escalates when Harvey is poisoned and dies, leaving Cora and Yifei exposed and on the run. They endure terrifying encounters, violent escapes, and growing paranoia, deepening the sense of a city under siege by both physical and spiritual threats.

Cora’s grief crystallizes into rage and defiance when she confronts the reality of systemic corruption and violence.

In a final symbolic act, Cora sets fire to the mayor’s house, a gesture aimed at placating the hungry ghosts of the victims and acknowledging her own role as a survivor and witness. Despite rituals meant to guide the dead, Cora remains haunted, carrying the weight of loss and injustice.

The story closes with Cora reclaiming the racial slur “bat eater” as an emblem of resilience in the face of hatred. Walking into the subway tunnels, accompanied by ghosts, she embodies the precarious space between memory and survival, loss and resistance, navigating a world still marked by violence, fear, and uncertainty.

Through Cora’s journey, the narrative confronts trauma and systemic racism head-on, revealing both the costs and the quiet strength required to endure.

Characters

Cora Zeng

Cora Zeng stands at the emotional and narrative center of Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng, portrayed as a deeply complex and conflicted young Asian American woman navigating a world filled with trauma, loss, and alienation. She embodies the tension between invisibility and resilience—haunted by the violent death of her sister Delilah and burdened by feelings of failure and inadequacy in comparison to Delilah’s ethereal lightness.

Cora’s internal world is fractured; she struggles with grief that is both raw and lingering, complicated by her cultural dislocation and family fractures. Her pragmatic skepticism clashes with traditional rituals imposed by relatives, reflecting her broader struggle to reconcile her heritage with her own beliefs and trauma.

Professionally, Cora works as a crime scene cleaner, a job that immerses her in the grotesque realities of death and violence, especially against Asian American women, reinforcing the story’s themes of systemic racism and marginalization. Psychologically, she experiences disturbing symptoms like dark spots in her vision, symbolizing the blurred boundaries between physical and mental trauma.

Despite her isolation, Cora’s relationships with coworkers like Harvey and Yifei offer moments of connection and solidarity, even as she battles paranoia, hallucinations, and a creeping sense of spiritual hunger tied to the supernatural “hungry ghosts. ” Throughout the narrative, Cora’s journey is one of painful survival, grappling with the ghosts of her past, the failures of justice, and the ongoing fight for identity and peace.

Delilah Zeng

Delilah Zeng exists both as a living presence and a haunting spectral figure within the story. In life, she is depicted as fragile, ethereal, and dreamlike—a young woman filled with aspirations of modeling and a desire to be remembered at the height of her youth and beauty.

Her violent death early in the narrative acts as the catalytic trauma that shapes the entire story, marking a brutal rupture in Cora’s world. Delilah’s death is not only physical but spiritual; her restless ghost embodies the concept of a “hungry ghost,” tormented by unresolved violence and the failure of traditional mourning rites.

Her appearances in the narrative—both in hallucinations and supernatural visions—force Cora to confront her unresolved grief and guilt. Delilah’s spectral presence is a haunting reminder of the cost of racialized violence and neglect, embodying both vulnerability and the terrifying persistence of trauma beyond death.

Harvey

Harvey is a key supporting figure in Cora’s life and work, serving as one of her coworkers in the grim profession of crime scene cleaning. He is characterized by a mixture of dark humor, emotional fragility, and a kind of weary camaraderie that offers Cora a rare sense of companionship amid the horror they face daily.

Harvey’s personal story, including his isolation and escapism through video games, contrasts with the grim reality of their work cleaning violent deaths, highlighting the varied ways individuals cope with trauma. His death—poisoned by a lethal chemical solvent—marks a devastating turning point in the narrative, intensifying Cora’s sense of vulnerability and underscoring the precariousness of their lives.

Harvey’s demise also reinforces the story’s themes of systemic violence and marginalization, as well as the ever-present threat hanging over those caught in the web of racialized hate and brutality.

Yifei

Yifei, another coworker and friend to Cora, is portrayed as pragmatic, fiercely determined, and spiritually grounded, offering a counterbalance to Cora’s haunted sensitivity. She brings an important supernatural and cultural dimension to the narrative through her belief in “hungry ghosts” and traditional rituals designed to appease restless spirits.

Yifei’s scars and stories about encounters with these ghosts deepen the story’s blend of folklore and psychological trauma, emphasizing the permeable boundary between the physical and spiritual realms. Her activism and refusal to remain silent about the serial murders of Asian women in Chinatown highlight her role as a protector and fighter, channeling grief into resistance.

The intensity of her friendship with Cora provides both emotional support and moments of tension, as their differing approaches to trauma and survival intersect. Yifei’s strength and cultural knowledge become vital in the rituals to calm Delilah’s spirit and confront the dark forces threatening them all.

Auntie Zeng

Auntie Zeng represents traditional cultural continuity and the weight of ancestral customs within the fractured family landscape. As a relative versed in ancestral rituals, she embodies the tension between old-world spiritual practices and Cora’s more skeptical, modern worldview.

Her presence introduces themes of ritual mourning, ghost month observances, and the spiritual importance of honoring the dead. Auntie Zeng’s rituals serve as both a source of comfort and discomfort for Cora, illustrating the difficult negotiation of cultural identity in the face of grief and trauma.

Her role underscores the story’s exploration of heritage, spirituality, and the ways in which cultural traditions attempt to grapple with loss and the supernatural.

Father Thomas

Father Thomas is a young minister who appears as a figure of spiritual authority and compassion but also embodies the alienation that Cora feels from religious communities. His presence in the cathedral crypt and his awareness of the fear and prejudice surrounding Cora highlight the story’s themes of exclusion and cultural misunderstanding.

The crypt setting symbolizes the burial of grief and the darkness that Cora must navigate both externally and internally. Though he attempts to offer support, Cora remains distant and mistrustful, underscoring her spiritual estrangement and the limitations of institutional religion to fully address the traumas of racialized violence and personal loss.

Cora’s Family (Father, Mother)

Cora’s immediate family situation is marked by distance and fragmentation. Her father’s return to China and her mother’s involvement in a cult represent physical and emotional absences that leave Cora isolated.

The lack of direct familial support and the presence of cultural dissonance amplify her loneliness and struggle for identity. These fractured family dynamics deepen Cora’s sense of being caught between worlds—culturally, emotionally, and spiritually—without a stable foundation from which to grieve or heal.

Themes

Trauma and Grief

The narrative of Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng explores trauma and grief as a continuous, pervasive presence that shapes Cora’s entire existence. The traumatic loss of her sister Delilah is not a singular event but an ongoing psychological burden that permeates Cora’s reality, altering her perception and interactions.

The depiction of her internal struggles—manifested through haunting visions, physical symptoms like the dark spots in her vision, and fractured mental states—reveals how trauma disrupts both mind and body, creating a painful liminal space where reality and memory collide. The repeated imagery of ghosts and hungry spirits serves as an externalization of Cora’s unresolved sorrow and guilt, symbolizing the inescapability of grief that refuses to be neatly contained or soothed by rituals or time.

Moreover, Cora’s fractured family dynamic, with members scattered, culturally disconnected, or engulfed in cult-like belief systems, compounds her isolation and underscores the alienation often experienced by those dealing with profound loss. The story neither offers a clean resolution nor romanticizes recovery; instead, it portrays trauma as a complex, messy state where moments of connection and defiance punctuate an otherwise oppressive experience of loss and loneliness.

Racism and Marginalization

Racial prejudice and systemic marginalization form a stark, unforgiving backdrop throughout the story, deeply affecting Cora and the Asian American community she inhabits. The pandemic setting, with its racial scapegoating and the labeling of COVID-19 as the “China Virus,” heightens existing xenophobic tensions and situates Cora’s personal tragedy within a broader societal crisis.

Acts of anti-Asian racism—such as the refusal of Uber service, violent attacks, and racial slurs like “bat eater”—are not isolated incidents but reflections of a structural hostility that infects everyday life. The narrative connects this racial violence to a chilling serial killer targeting Asian women, a symbol of the deadly consequences of dehumanization and hate.

Police complicity and political suppression of the investigation further reveal systemic indifference and corruption that compound the vulnerability of marginalized communities. Cora’s eventual reclamation of the slur “bat eater” signals a powerful act of resistance, transforming a weapon of hatred into an emblem of survival and identity affirmation.

The persistent threat of racial violence and the fraught navigation of public spaces illustrate how racism constrains, endangers, and defines the lives of people like Cora, complicating their search for safety and justice.

Identity and Cultural Dislocation

Cora’s identity is caught between worlds, creating a profound sense of cultural dislocation that echoes throughout the narrative. Her life unfolds at the intersection of Asian traditions and American urban reality, neither fully embraced nor easily reconciled.

The contrasting beliefs and practices within her family—from her mother’s involvement in a cult, Auntie Zeng’s traditional rituals, to Auntie Lois’s Christian faith—highlight the tensions and contradictions inherent in cultural heritage when confronted by trauma and modernity. Cora’s skepticism and pragmatic disbelief clash with these spiritual systems, intensifying her alienation from both her family and cultural roots.

This conflict mirrors her internal struggle with belonging and self-definition, as she resists simple categories while grappling with inherited grief and racialized violence. The supernatural elements—the hungry ghosts, rituals, and ghost feast—serve as a cultural language for processing loss, yet also underscore the difficulty Cora faces in accepting or fully understanding these modes of mourning.

Her isolation in a small Chinatown apartment, obsessively sanitized against an “unclean” world, further symbolizes the tension between her need for control and her vulnerability to forces beyond her grasp. Identity here is portrayed as fractured, fluid, and fraught, shaped by history, trauma, and a search for meaning amid disintegration.

Survival and Resistance

Despite the overwhelming darkness of loss, racism, and psychological torment, the narrative insists on the possibility of survival and defiance. Cora’s work as a crime scene cleaner, though grim and alienating, offers a strange form of agency, a way to confront death and violence head-on rather than retreat from it.

Her relationships with Harvey and Yifei provide a network of shared endurance, each coping in distinct ways—through dark humor, activism, or pragmatic stoicism. The rituals and ghost feast symbolize attempts to reclaim power over death and loss, blending cultural memory with acts of symbolic defiance.

Furthermore, the uncovering of the serial killer’s identity and police corruption becomes a catalyst for a personal and communal reckoning, compelling Cora to resist silence and invisibility imposed by systemic forces. Her act of arson against the mayor’s house functions as a radical protest against political complacency and a ritualistic attempt to feed the hungry ghosts, merging justice-seeking with spiritual reckoning.

The final scenes of Cora reclaiming the slur and walking into the subway tunnels alongside ghosts speak to a courageous embrace of the shadowy realities she faces—a refusal to be erased or broken. Survival here is not passive endurance but active resistance, a gritty insistence on presence, memory, and justice in a hostile world.

The Supernatural and Spiritual Belief

The interplay between supernatural elements and spiritual beliefs deeply shapes the story’s emotional and symbolic landscape. Ghosts and spirits are not mere metaphors but active agents influencing the characters’ lives, blurring the line between psychological trauma and paranormal experience.

The concept of “hungry ghosts,” traditional Chinese folklore spirits suffering from insatiable hunger due to neglect in life or death, resonates with Cora’s feelings of loss, guilt, and the incompleteness of mourning rituals. This spiritual framework allows the narrative to explore grief and trauma in a culturally specific way that also speaks to universal human fears of abandonment and the unknown after death.

Rituals such as the ghost feast and the burning of joss paper create spaces where the living and dead communicate, offering moments of catharsis and confrontation. The tensions between different religious beliefs—Christianity, ancestral worship, cult-like practices—highlight the fractured spiritual landscape Cora inhabits, mirroring her fractured psyche.

The supernatural presence also accentuates the narrative’s exploration of justice beyond the physical realm, as restless spirits symbolize the need for acknowledgment, remembrance, and reconciliation. This theme enriches the story’s emotional texture, emphasizing how belief systems and spiritual acts can serve as both comfort and confrontation amid trauma and loss.

Isolation and Alienation

Throughout the story, isolation permeates Cora’s life, reflecting the emotional, cultural, and social alienation experienced by individuals grappling with trauma and marginalization. Her physical solitude—living alone in a small apartment, obsessively cleaning, separated from much of her family—mirrors the emotional distances she maintains as a protective mechanism.

The pandemic context amplifies this isolation, with deserted streets and a city emptied by fear and racism serving as a bleak backdrop to her internal desolation. Cora’s relationships are strained by mistrust, cultural misunderstandings, and the burden of shared trauma, leaving her suspended in a liminal space where connection is fraught and fragile.

The suspicion toward medical professionals, fear of being perceived as mentally unstable, and her struggle to communicate her experiences illustrate the alienation of those whose pain does not easily fit societal narratives. Moreover, her invisibility, both self-imposed and externally imposed by racism and grief, underscores the erasure many marginalized individuals face.

This alienation intensifies the story’s exploration of how loneliness can become both a prison and a crucible for survival, forcing Cora to confront the darkest parts of herself while searching for solidarity in a world intent on exclusion.