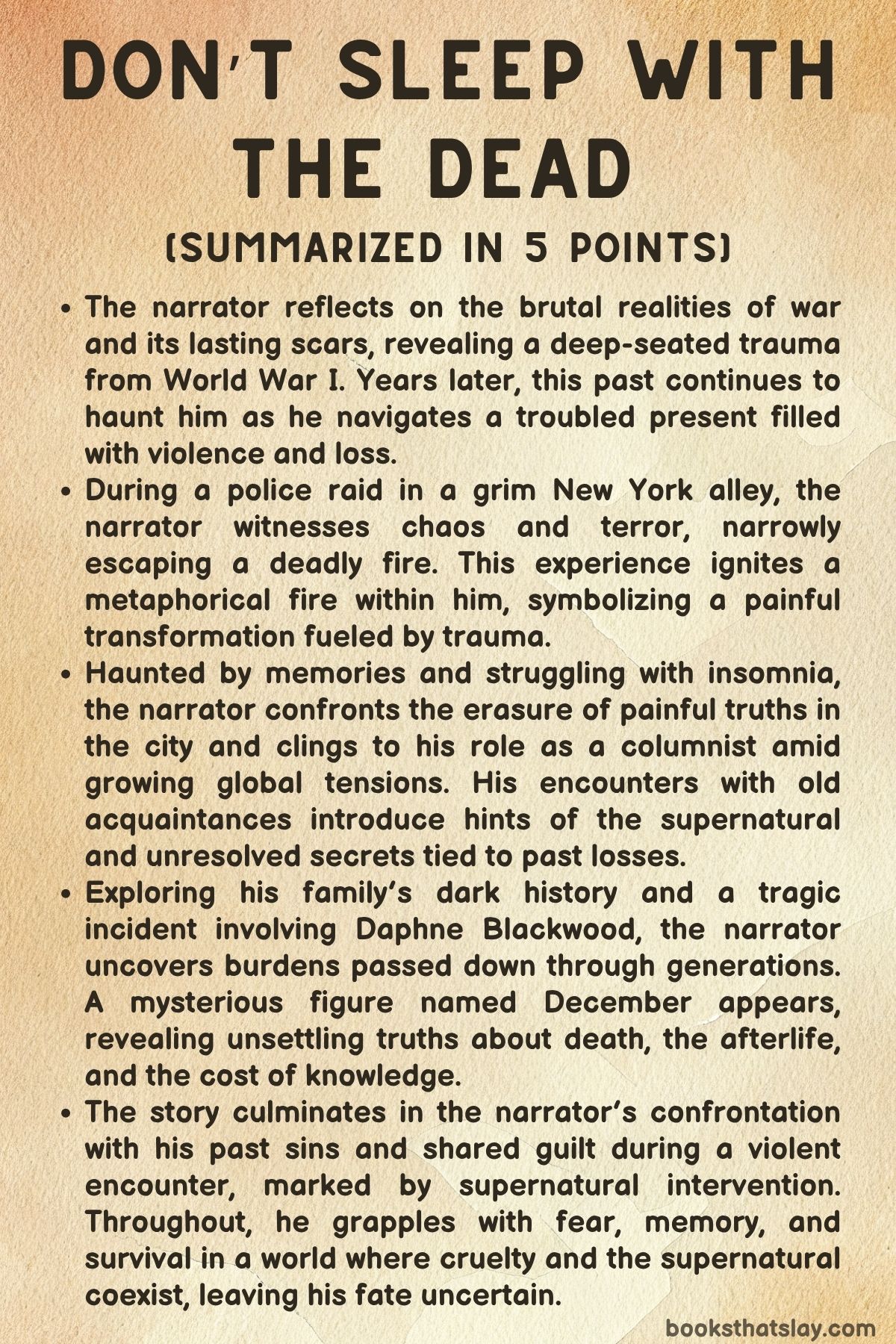

Don’t Sleep With The Dead Summary, Characters and Themes

Don’t Sleep With The Dead by Nghi Vo is a dark, atmospheric exploration of trauma, memory, and the lingering shadows of history. Set against a backdrop that moves from the horrors of World War I to the haunted streets of New York, the story follows a narrator grappling with violence, loss, and supernatural forces.

The novel intertwines personal and family secrets with mythic and spectral elements, creating a world where the dead return and the past refuses to stay buried. It challenges the reader to confront the cost of memory, the weight of guilt, and the complex nature of identity in a fractured, eerie reality.

Summary

The story opens with the narrator reflecting on the brutal experience of war, specifically recalling the horrific events before a major battle in World War I. The narrator rejects a comforting lie told by a first sergeant—that the worst finally happening makes it bearable—insisting instead that the worst was nothing but suffering and death.

This memory casts a long shadow over the narrator’s life, marking them with trauma that never truly fades.

Years later, the scene shifts to a dark New York alley during a police raid where the narrator, alongside a group of men including journalists and professionals, is trapped. The alley, grim and hostile, is described as a “killing field,” guarded with dogs and surrounded by police.

The narrator’s mindset oscillates between grim acceptance and sharp sarcasm, revealing deep inner fear and turmoil. Nearby stands a frightened young boy, vulnerable and cold, who receives harsh survival advice from the narrator—a stark reminder of the brutal realities faced by those caught in the city’s dangerous underworld.

Tensions escalate when a man named Perry Sloan resists the police, provoking a violent crackdown. The situation descends into chaos when a glass salamandrina is smashed, plunging the area into darkness.

A sudden fire breaks out, leading to panic, people being trampled, and a desperate struggle to escape the flames. The narrator narrowly survives, wounded and gasping, carrying with them a literal and symbolic ember—a fiery reminder that trauma has changed them forever.

In the aftermath, the narrator is haunted by insomnia and fragmented dreams filled with memories of violence and loss. Despite the severity of the raid, the city’s newspapers remain silent, suggesting a societal tendency to ignore or suppress difficult truths.

The narrator clings to their job as a columnist amid the looming threat of another war, trying to hold onto routine while the world edges closer to catastrophe.

A surreal conversation with an old acquaintance, Jordan Baker, reveals supernatural undertones. Jordan speaks cryptically about the dead returning, including a figure named Gatsby who has apparently come back in some form.

Their dialogue explores themes of memory, loss, and unresolved emotions from a shared past, hinting at secrets and regrets that haunt both characters.

The story then traces the narrator’s family history, revealing a dark legacy beginning with an ancestor, Leith Carraway, who escaped the Civil War by swapping faces with another man. This act of evasion sets a pattern of avoiding responsibility and passing down burdens, connecting to the narrator’s own struggles with guilt, particularly over a tragic incident involving a girl named Daphne Blackwood.

Searching for answers about Gatsby’s fate, the narrator meets a mysterious figure named March at the Gates, a liminal place where devils make deals and share secrets. March, appearing in disturbing forms, offers cryptic insights about the afterlife and warns that Gatsby’s soul may have been consumed, leaving no hope for resurrection.

This grim revelation deepens the narrator’s despair and sense of loss.

The journey continues to a surreal hospital setting where reality blurs with nightmare. Here, the narrator encounters strange visions and a woman made of wax who offers unsettling hospitality and vague clues.

Despite the horror, the narrator presses on, marked by physical pain symbolized by a burned hand that reveals words beneath the skin—suggesting their identity and fate are written in suffering.

A violent confrontation with Ross Hennessey, a figure from the narrator’s past, forces them to face buried sins and shared guilt. The conflict uncovers a dark event involving Daphne Blackwood, exposing the narrator’s internal torment and the heavy burden of past misdeeds.

The fight ends abruptly when a demon appears, killing Hennessey and sparing the narrator, who flees confused and frightened.

The narrator is overwhelmed by fear and haunted by ghosts both literal and metaphorical, struggling to survive in a world filled with cruelty, betrayal, and supernatural menace. Their internal battle—between cowardice and courage, memory and forgetting, reality and nightmare—captures the novel’s intense atmosphere of uncertainty and shadow.

Later, the narrator reflects on the blood on their face after a violent encounter with Hennessey. The blood is a stark symbol of trauma that cannot be washed away.

While the narrator shows emotional detachment toward Hennessey, memories of Daphne Blackwood flood them with horror, sorrow, and guilt. Daphne’s disappearance and suffering linger as unresolved pain, contrasting with the narrator’s own life marked by avoidance and silence.

The narrator realizes they, like Hennessey, could suppress these memories and move on, but doing so would betray those who remember the truth. A figure known as December, a dark and supernatural man with a severed throat yet still alive, is introduced as a mysterious observer who later reveals he killed Hennessey.

December embodies a liminal, infernal presence within the story.

The narrator’s call to their mother uncovers a family history of denial and forgetting related to Daphne Blackwood. Daphne’s troubles and disappearance are minimized or erased by family members, reflecting a broader theme of ignoring painful truths.

The narrator refuses this erasure, carrying the weight of memory and loss.

As the narrator wanders through snowy, deserted New York streets, their isolation grows alongside the presence of death and violence. Visits to familiar places yield only emptiness, symbolizing the narrator’s loneliness and unresolved trauma.

A phone conversation with Jordan highlights their differing attitudes toward the past and memory. Jordan dismisses the narrator’s obsession with Gatsby, portraying him as a man who made deals with dark forces and ultimately lost.

The narrator insists on uncovering the truth, underscoring the tension between confronting and escaping painful histories.

The narrator eventually meets December in a strange place called August 7th, a room steeped in magic and history. December offers the narrator a chance to claim a new identity, free from inherited lies and burdens.

Their conversation reveals December’s bitterness and motivations, including his killing of Hennessey “because I wanted to. ” This encounter blends memory, desire, and supernatural menace.

Reflecting on Gatsby, the narrator recognizes him as a symbol of a corrupted American Dream filled with broken hopes and selfish ambition. The narrative culminates in an intimate, complex moment between the narrator and Gatsby, where love, cruelty, memory, and identity collide.

Gatsby offers the narrator a symbolic gift—a heart on paper—suggesting the possibility of rewriting one’s story despite trauma and death. The ending remains ambiguous, with the narrator caught between past and present, reality and illusion, waiting for what comes next.

Throughout the novel, themes of memory, trauma, identity, and the burden of the past are explored in a noir-tinged narrative that mixes supernatural elements with literary reflections on myth, history, and the American Dream.

Characters

Nick Carraway

The narrator Nick is a deeply haunted figure, burdened by trauma from both war and personal loss. Their experience in World War I shapes much of their worldview, especially the cynical rejection of comforting lies such as the “worst finally happening.” This trauma leaves a lasting scar, reflected in their insomnia, nightmares, and persistent memories that refuse to fade.

In the urban chaos of New York, the narrator’s survival instincts are tempered by cold realism, shown in their pragmatic advice to the frightened boy during the police raid.

Throughout the story, the narrator is caught in a liminal space between courage and cowardice, memory and forgetting, reality and nightmare. Their internal conflict is intensified by an ancestral legacy of evasion and guilt, particularly tied to the tragic figure of Daphne Blackwood.

The narrator’s interactions with supernatural entities and ghostly figures like March and December underscore their struggle to comprehend and accept the darker truths of existence. Their emotional detachment, especially toward figures like Ross Hennessey, contrasts sharply with the raw, unresolved horror tied to Daphne, highlighting the selective and painful nature of memory.

Despite this, the narrator clings to their identity as a columnist and a seeker of truth, though this pursuit continually exposes them to both psychological and physical harm. Ultimately, they embody the complex interplay of suffering, endurance, and the desire for redemption amid a shadowy world fraught with cruelty and supernatural menace.

Perry Sloan

Perry Sloan emerges briefly but vividly as a figure of resistance amid the raid’s chaos. His refusal to submit quietly to police demands and the violent consequences he faces symbolize the harsh realities of power and repression in the city’s underbelly.

Perry’s confrontation with authority serves as a catalyst for the outbreak of panic and violence, emphasizing themes of injustice and the volatility of oppressed communities. Though his role is relatively limited, Perry represents the courage to resist, however futile or dangerous, against oppressive forces.

Jordan Baker

Jordan Baker acts as a pragmatic, somewhat cynical foil to the narrator’s intense obsession with memory and the supernatural. Their conversation reveals a shared past marked by secrets and regret, and Jordan’s worldview leans toward dismissing the past as a burden best left behind.

She challenges the narrator to face difficult truths about the return of the dead and the meaning of Gatsby’s spectral presence, embodying a grounded skepticism in contrast to the narrator’s emotional turmoil. Jordan’s practicality and emotional distance provide a critical counterpoint to the narrator’s haunted introspection, highlighting the tension between confronting painful history and choosing to move on.

Gatsby

Gatsby appears as a spectral, symbolic figure, representing shattered dreams, ambition, and the corrupted American Dream. His return in some form—part ghost, part memory—serves as a focal point for the narrator’s quest for truth and meaning.

Gatsby’s story, including his deals with Hell and ultimate loss, underscores themes of selfishness, longing, and broken love. The intimate yet painful encounter between Gatsby and the narrator reveals complex layers of desire and disillusionment, as Gatsby’s yearning is shown to be intertwined with illusion rather than genuine love.

Gatsby’s symbolic gesture of offering the narrator a “present” to rewrite their story suggests a faint hope for healing and renewal, even amid enduring ambiguity.

Leith Carraway

Leith Carraway, the narrator’s great-uncle, is a shadowy ancestral figure whose choice to swap faces and evade the Civil War sets a pattern of avoidance and burden-shifting within the family lineage. This legacy haunts the narrator, linking past sins to present suffering and complicating their sense of identity.

Leith embodies themes of cowardice, disguise, and the cost of escaping one’s duties, casting a long, dark shadow over the narrator’s personal and familial history.

March

March is a supernatural and unsettling entity encountered by the narrator at the Gates, a liminal realm where devils trade favors and secrets. Taking on various disturbing forms, March provides cryptic insights into the afterlife and the terrible costs of forbidden knowledge.

This figure symbolizes the dark mysteries that lie beyond death and the painful consequences of seeking truth in a world ruled by shadowy powers. March’s revelations about Gatsby’s consumed soul deepen the narrator’s despair and highlight the inescapable nature of loss and corruption.

December

December is a mysterious, dark figure resembling the narrator but marked by a gruesomely severed throat, embodying a supernatural, infernal presence. His complex motivations and chilling confession—that he killed Ross Hennessey simply “because I wanted to”—introduce themes of fatalism, violence, and the blurred lines between human and demonic agency.

December’s offer to the narrator to claim a “real” name and face touches on desires for transformation and liberation from inherited identities, yet also reflects deep ambivalence and fear of losing oneself. His presence weaves together memory, desire, and menace in an intimate and unsettling relationship with the narrator.

Daphne Blackwood

Daphne Blackwood is a tragic and haunting figure whose suffering, disappearance, and the surrounding silence exemplify the painful weight of forgotten or suppressed trauma. The narrator’s profound emotional response to Daphne contrasts with the cold denial from her family, revealing themes of memory, guilt, and the erasure of uncomfortable truths.

Daphne’s story represents the casualties of familial and societal neglect, and her legacy continues to torment the narrator, underscoring the complex interplay of loss, horror, and unresolved grief.

Themes

War and Its Lasting Trauma

The narrative confronts war not just as a historical event but as a lingering psychological wound that refuses to heal. The narrator’s reflection on the brutal battle of Cantigny during World War I strips away any romantic notions of war as noble or cleansing.

Instead, the war is an unrelenting source of loss, fear, and haunting memories. The concept of “the worst finally happening” is debunked as a false comfort; the worst does not bring peace or resolution but deepens the trauma and embeds it into the psyche.

This trauma extends beyond the battlefield, infiltrating the narrator’s civilian life with insomnia, fragmented dreams, and an emotional numbness that isolates him from others. The physical and psychological scars of combat merge, showing how the brutality experienced during war perpetuates a cycle of internal violence.

The war’s shadow looms over the entire story, influencing not just the narrator’s personal struggles but also symbolizing broader societal fractures. The inability to forget or move past such experiences manifests as a spectral presence—ghosts of the dead and memories that refuse to be silenced.

This theme speaks to the pervasive and enduring nature of trauma, highlighting that the aftermath of war is not confined to the battlefield but becomes a lifelong battle within the mind and soul.

Memory, Forgetting, and the Burden of the Past

Memory operates as both a tormentor and a keeper of truth within the narrative. The narrator’s struggle is deeply entwined with what is remembered and what is forcibly forgotten, both personally and collectively.

Family histories and personal tragedies, like the story of Daphne Blackwood, exemplify how painful truths are often suppressed or erased to avoid confrontation with guilt or loss. Yet, the silence surrounding these memories does not erase their weight; instead, it creates a lingering presence that continues to affect the narrator’s identity and actions.

This tension between remembering and forgetting is mirrored in society’s broader refusal to acknowledge certain events, as seen in the city newspapers’ deliberate silence about the raid. The act of forgetting becomes an act of violence itself—an attempt to erase inconvenient or painful realities, but one that ultimately leaves wounds unhealed.

The narrator’s fixation on uncovering and confronting these buried memories underscores the human need to face the past honestly, even when it brings discomfort or sorrow. This theme exposes how memory is tied to identity and morality, challenging the notion that erasure can lead to peace.

Instead, the past demands recognition, and the burden it imposes shapes the present in inescapable ways.

The Supernatural and the Intersection of Life and Death

Supernatural elements permeate the story, complicating the boundary between life and death and adding layers of meaning to the narrator’s journey. The presence of figures like March and December, who inhabit ambiguous realms and possess eerie, otherworldly traits, symbolizes the inescapable influence of death on the living.

These entities serve as gatekeepers to forbidden knowledge and painful truths, forcing the narrator to confront realities that ordinary human experience cannot encompass. The recurring references to souls being consumed, the dead returning, and transactions with devils underscore a world where spiritual and metaphysical forces are entwined with human suffering and fate.

This blurring of reality and the supernatural reflects the narrator’s internal turmoil, as trauma warps perception and invites encounters with the uncanny. Moreover, the supernatural becomes a metaphor for the consequences of ambition, guilt, and unresolved grief—Gatsby’s fate as a soul that cannot return intact is emblematic of the destructive costs of broken dreams and moral compromise.

The theme suggests that confronting death and the unknown is necessary for understanding life’s deeper truths, but such confrontations are often harrowing and destabilizing.

Identity, Legacy, and the Struggle for Self-Definition

The story wrestles with the complexities of identity, particularly how it is shaped by family legacies, societal expectations, and the past’s unresolved burdens. The narrator’s family history, marked by deception and evasion of responsibility—such as the great-uncle who swapped faces to avoid the Civil War—establishes a foundation of inherited guilt and fractured identity.

This legacy haunts the narrator, who struggles to define himself independently of the sins and secrets passed down through generations. The motif of faces and names—offered through the mysterious figure December—points to the fluidity and fragility of identity itself.

The narrator’s hesitation to claim a “real” name or face reveals a conflict between desire for transformation and the loyalty or entrapment in inherited narratives. This tension reflects the broader human challenge of carving out an authentic self amid the pressures of history, memory, and social roles.

The story also explores how identity is intertwined with trauma, as wounds and regrets become embedded in the self. The narrator’s journey suggests that self-definition requires grappling with painful truths and the courage to confront what one has inherited, rather than seeking escape through denial or reinvention.

The theme exposes the difficulty of reclaiming agency over one’s life when bound by past shadows.

The Elusiveness of Truth and the Complexity of Redemption

Throughout the narrative, truth remains elusive, layered beneath memories, denials, and supernatural mysteries. The narrator’s quest for answers about Gatsby and the past reveals that truth is not a simple, comforting clarity but a complex, often painful revelation that challenges existing beliefs.

The story portrays truth as something that comes with a cost—emotional, spiritual, and sometimes physical. Encounters with otherworldly beings who offer cryptic insights reinforce the idea that truth is guarded and costly to attain.

Redemption is also portrayed ambiguously; it is not an assured outcome but a fragile possibility that requires confronting darkness and accepting loss. The symbolic gesture of Gatsby offering a “present” to rewrite the narrator’s story suggests hope for healing and transformation, yet the narrator remains caught in uncertainty and liminality between past and future, illusion and reality.

This theme interrogates the nature of forgiveness, the possibility of change, and whether true redemption can be achieved after profound trauma and moral failure. It challenges the reader to consider how individuals wrestle with the consequences of their actions and the narratives they construct to make sense of their lives.

The narrative’s refusal to provide easy answers emphasizes the complexity of human experience and the enduring struggle to reconcile with one’s past.

Urban Alienation and the Harshness of Modern Life

The story’s setting in a grim, oppressive urban environment underscores the theme of alienation and survival in a world marked by cruelty and indifference. The bleak descriptions of the New York alley, with its hostile police, vicious dogs, and desperate inhabitants, paint a picture of a city where safety is scarce and vulnerability is punished.

The narrator’s cold advice to the frightened boy reflects a hardened realism shaped by exposure to relentless hardship. The raid and subsequent chaos symbolize the fragility of life in the modern metropolis, where violence and fear can erupt suddenly, leaving individuals isolated and wounded.

The city becomes a landscape of existential loneliness, where connections are fleeting and trust is rare. The narrator’s wandering through snowy streets and deserted parks further illustrates the deep sense of disconnection and the search for meaning or solace amid urban decay.

This theme captures the alienation experienced by those on the margins of society and the psychological toll of living in a world where brutality and neglect coexist. It highlights how the modern city, far from being a place of opportunity or community, often exacerbates isolation and suffering.