The Eights by Joanna Miller Summary, Characters and Themes

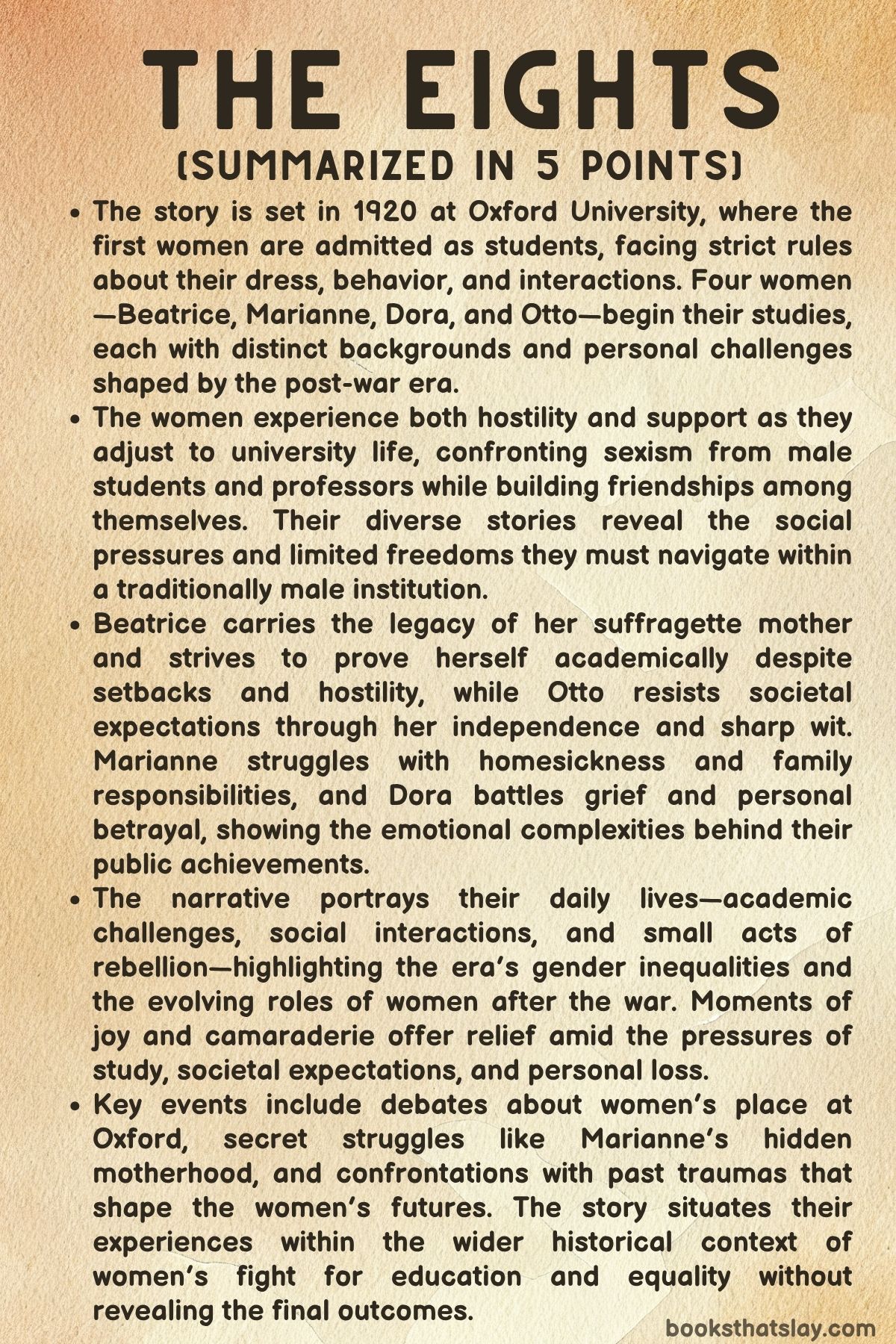

The Eights by Joanna Miller is a historical novel set in 1920 at Oxford University, focusing on the first women admitted as undergraduates. It explores the lives of four distinct young women—Beatrice, Marianne, Dora, and Otto—each from different backgrounds, coming to terms with the challenges of a male-dominated academic world and the social expectations of their time.

The story captures their struggles with rigid university rules, personal grief, and societal pressures as they navigate new freedoms and restrictions after World War I. Through their evolving friendships and experiences, the novel offers a detailed look at the early stages of women’s higher education and the broader fight for gender equality.

Summary

The narrative begins on October 7, 1920, a landmark day as the first women matriculate at Oxford University’s St. Hugh’s College.

The story opens by describing the university’s strict dress codes and rules for women students—requirements for gowns and caps, curfews, chaperones, and limited interaction with male students. These rules illustrate the cautious, often patronizing attitude toward integrating women into a traditionally male institution.

Four young women—Beatrice Sparks, Marianne Grey, Dora Greenwood, and Ottoline “Otto” Wallace-Kerr—start their academic journey at Oxford. Each girl has a unique story and motivation.

Beatrice is the daughter of a militant suffragette, carrying the weight of her family’s political legacy and driven by a fierce ambition. Marianne struggles with homesickness and worries for her sick father left behind in the countryside.

Dora, haunted by the loss of her fiancé and brother in the war, seeks solace and purpose in academia. Otto, independent and sharp-witted, uses mathematics as a refuge from her family pressures while wrestling with her desire for freedom.

On their first day, the women face hostility and mockery from male students during matriculation. Otto bravely stands up to some of the jeering boys, defending the group’s dignity.

Though challenged, the four begin to support each other, adapting to the rigid university regulations and their new environment. The matriculation ceremony itself is bittersweet: the women attend the Gothic Divinity School, separated physically from the men who matriculate in the Sheldonian Theatre.

This separation underscores the persistent inequalities despite the historic moment.

Their college life is shaped by strict rules that limit freedom and social interactions. The women share meals, stories, and hopes in each other’s company.

Beatrice speaks of her mother’s suffragette activism and her own high ambitions. Otto challenges stereotypes about women’s wartime roles, recounting her ambulance-driving experience.

Marianne admits her loneliness and care responsibilities. Dora reveals her struggle with grief.

Their conversations mix determination with moments of humor and warmth as they plan their studies and extracurricular activities, balancing hopes with the realities they face. The photograph of the four friends, known as “the Eights,” symbolizes their unity and the start of a shared journey.

The academic environment is demanding and unwelcoming at times. Dora’s experience with a harsh tutor shows the intellectual rigor they must endure while coping with personal losses from the war.

As Dora tentatively adapts to Oxford’s academic culture, the story highlights the opportunities and sacrifices involved in this pioneering time for women.

The narrative unfolds further through letters, diary entries, and scenes portraying the women’s first term at Oxford. Otto humorously compares college life to prison, describing strict routines, compulsory chapel, communal meals, and the constant pressure of exams.

Despite these restrictions, Otto negotiates small freedoms—secret morning coffee with Maud, the college scout, and even forbidden wine deliveries. The limited career prospects for women are clear, with degrees qualifying mainly for secretarial or teaching roles, reflecting gender constraints of the era.

Marianne’s perspective reveals the unseen labor and social challenges in the college. Maud, the scout, handles chores, highlighting class and gender divides.

Marianne struggles with living closely among other women but gradually bonds with the group. Their friendship blossoms through late-night talks, tea parties, and shared laughter, providing joy amid academic pressures.

Dora writes about the historic awarding of degrees to women at Oxford, a hard-won victory attended by women of all ages. This milestone is celebrated but also tempered by ongoing societal limitations such as restricted voting rights.

Dora’s account reveals tensions within the group, especially regarding Beatrice’s politically fiery mother, Edith Sparks. Edith delivers a stirring speech advocating women’s equality and condemning economic and social hardships faced by women, reflecting the broader feminist activism of the time.

Beatrice’s flashbacks reveal the dangers and hostility suffragettes faced, including a traumatic assault at a rally and her mother’s dismissive attitude toward her efforts. These experiences illustrate the resilience required by women challenging societal norms.

The narrative also touches on everyday realities—bicycle lessons, balancing academic and social life, and encounters with kindness and condescension from male students and college officials. Otto’s painful dental visit and secret nighttime escapades reveal personal struggles beneath her confident exterior.

Disabled war veterans in the parks serve as reminders of the war’s lingering impact.

Later, the focus shifts to family dynamics. Otto’s older sister Caro marries a wealthy American, Warren Powell II, in a high-profile wedding that signals traditional gender roles and social expectations.

Otto and her friends candidly discuss marriage as a strategic but flawed institution. Otto herself resists marriage proposals, determined to pursue education and independence instead.

Her relationship with Teddy, a war-injured veteran, highlights different forms of companionship and personal autonomy in the post-war era.

One pivotal scene is the Oxford Union debate on whether women belong at Oxford. Beatrice, as JCR president, presides over an event marked by sexist opposition from male students, who mock and dismiss the idea.

Advocates, including Edith Sparks and Vera Brittain, argue for women’s educational rights, citing recent legal advances. Vera Brittain’s defense narrowly wins the debate, symbolizing a fragile victory for gender equality.

Interwoven with these public moments are the personal stories of Marianne Ward, a war widow and secret mother enrolled under a false name, highlighting the stigma faced by women balancing motherhood and education. Despite fear of discovery, she perseveres academically, driven by the hope for a better life.

The term’s activities—rowing, debating, theater—show the women forging friendships and challenging gender roles. A symbolic balloon ride over Oxford reflects their yearning for freedom and a broader view beyond societal limitations.

Personal tensions also emerge, such as Dora’s confrontation with her former fiancé Charles Baker, whose betrayal haunts her.

The story closes with an author’s note blending historical fact and fiction, paying tribute to the real women who fought for educational equality at Oxford. The novel captures the complexities of progress, the courage needed to break new ground, and the enduring impact of these early female students’ experiences in the 1920s.

Characters

Beatrice Sparks

Beatrice Sparks emerges as a tall, politically charged young woman shaped by her militant suffragette mother, Edith Sparks. Her character is defined by a fierce desire to prove herself beyond the shadow of her mother’s activism, embodying a blend of determination, intellect, and idealism.

From her early days in the Women’s Volunteer Reserve where she accepted the mundane role of typist with quiet resolve, to her struggles within the rigid and often hostile walls of Oxford, Beatrice’s journey highlights the tension between personal ambition and the societal constraints of the era. Her experience with academic sexism, such as being publicly ejected from a lecture, reveals her resilience and the emotional cost of pioneering spaces for women.

Beatrice’s relationships, particularly her admiration and unspoken romantic feelings for Ursula Singh, deepen her character by showcasing her vulnerability and longing for connection amidst her drive for achievement. Throughout, Beatrice symbolizes the evolving role of women who carry both the weight of legacy and the hope for progress in a changing world.

Marianne Grey

Marianne Grey presents a softer, more fragile counterpart within the group. She is marked by homesickness and a deep sense of responsibility for her ailing father and, later, her daughter Connie.

Her narrative exposes the less visible burdens women carried—especially those balancing family obligations with academic aspirations. Marianne’s secret enrollment under a false name to continue her education while concealing her motherhood adds layers of complexity to her character, reflecting the stigma and societal pressures surrounding women’s roles at the time.

Her introspective and cautious nature contrasts with her peers’ bolder personalities, making her a relatable figure who embodies the quiet endurance and emotional struggles of many women striving for self-betterment under restrictive conditions. Through Marianne’s eyes, the reader witnesses both the intimate realities of female friendship and the broader social challenges of post-war England.

Theodora “Dora” Greenwood

Dora Greenwood’s character is deeply haunted by personal loss and emotional turmoil. Grieving the deaths of her brother and fiancé during the war, her pain shapes much of her behavior and academic performance.

Dora’s story arc includes a profound betrayal when her presumed-dead fiancé, Charles Baker, reappears with deceit, shattering her trust and driving her toward a defiant rejection of societal expectations. Her eventual rustication from Oxford after a public outburst signifies a powerful act of rebellion and self-preservation.

Dora’s cutting of her hair and symbolic rejection of her past reflect both her grief and desire for autonomy. Through Dora, the narrative explores the psychological scars of war and the limited options for women who faced emotional as well as institutional constraints.

Despite her struggles, Dora remains a vital figure, embodying the complex interplay of vulnerability, resilience, and resistance in a period of social upheaval.

Ottoline “Otto” Wallace-Kerr

Otto Wallace-Kerr is characterized by her sharp wit, independence, and a restless spirit seeking escape from family pressures and societal norms. Her relationship with her older sister Caro, who saved her life at birth and later marries into wealth and privilege, adds tension and complexity to Otto’s narrative, highlighting themes of gratitude, rivalry, and differing aspirations.

Otto’s pursuit of mathematics offers her a sense of certainty and control, contrasting with her inner battles around identity and rebellion against traditional female roles. Her bold confrontation with male students during matriculation and secret nocturnal adventures reveal her courage and desire to carve out her own space.

The contrast between Otto’s refusal to marry and her interactions with Teddy, a disabled war veteran proposing a practical companionship, further illustrates her struggle to define autonomy on her own terms. Otto’s humor, resilience, and conflicted emotions make her a compelling symbol of the young women’s fight for independence in the post-war era.

Edith Sparks

Though a secondary character, Edith Sparks, Beatrice’s mother, plays a pivotal role as a militant suffragette whose fiery activism and dismissive attitude toward her daughter’s quieter achievements shape much of Beatrice’s internal conflict. Edith embodies the older generation of feminist warriors, passionate and uncompromising, who challenged the patriarchal establishment directly but sometimes at the cost of personal relationships.

Her public speeches advocating women’s equality serve as a reminder of the broader social movement underpinning the characters’ struggles. Edith’s tension with Beatrice, especially around the perceived significance of their roles in the fight for women’s rights, highlights generational differences in activism and the personal sacrifices involved in such a fight.

Caro Wallace-Kerr

Caro is Otto’s older sister and represents the socially conventional path available to women of their class—marriage into wealth and stability, symbolized by her wedding to American Warren Powell II. Her relationship with Otto is marked by gratitude and complexity, with Caro’s act of saving Otto’s life creating an enduring bond, yet Caro’s choices reflect traditional expectations, contrasting sharply with Otto’s rebellious spirit.

Caro’s marriage introduces themes of social control and gender dynamics within elite society, as well as the compromises women made to secure their futures. She personifies the conventional “successful” woman of the time, offering a foil to Otto’s quest for independence.

Maud (The Scout)

Maud serves as a grounding figure in the narrative, representing the working-class women who supported the lives of female students through household labor and caretaking. Her role highlights class and gender divides, providing a realistic depiction of the unseen labor that underpinned the students’ academic lives.

Maud’s interactions with Marianne and Otto underscore the different social strata coexisting within the college, and her diligence and kindness provide a subtle counterpoint to the more privileged students’ struggles. Maud embodies the often overlooked support systems essential to the collegiate experience of women in this era.

Teddy

Teddy is a severely wounded war veteran whose relationship with Otto offers a nuanced exploration of post-war realities. Despite his physical injury and impotence, Teddy’s proposal of marriage based on companionship challenges traditional romantic ideals and reflects the practical considerations shaping relationships at the time.

His character adds depth to the narrative’s portrayal of war’s long-term impact on personal lives and the redefinition of intimacy and partnership in a changed society. Teddy’s presence in Otto’s story highlights the intersections of trauma, resilience, and societal expectations.

Ursula Singh

Ursula Singh is a peer admired by Beatrice, notable for her boldness and articulate presence. Though less detailed in the summaries, Ursula symbolizes the emerging diversity and progressive spirit within the academic community.

Beatrice’s unspoken romantic fixation on Ursula adds layers of complexity to Beatrice’s character, reflecting themes of identity, attraction, and emotional discovery that run beneath the surface of the group’s public struggles. Ursula represents the possibility of new connections and challenges to traditional norms within the women’s collegiate experience.

Themes

Gender Inequality and the Struggle for Women’s Rights

The tension between women and entrenched male-dominated institutions is a persistent undercurrent throughout The Eights. The narrative exposes the deeply ingrained sexism women faced, not only in the broader society but particularly within academia, a bastion of tradition and privilege.

The strict dress codes, curfews, and paternalistic regulations imposed on female students reflect the university’s desire to control and limit women’s presence, illustrating the larger societal reluctance to accept women as equals in intellectual and social spheres. The mockery and hostility from male students during matriculation vividly depict the resistance women encountered just for daring to claim their rightful place in education.

The Oxford Union debate scene further crystallizes this struggle, where arguments that women’s presence would degrade the university’s reputation or divert resources reveal how gender biases were institutionalized and defended with fierce conviction. However, the narrative does not simply present these challenges as external obstacles; it explores how women internalize and react to these constraints, showing both moments of despair and bursts of defiance.

The activism of characters like Edith Sparks and the symbolic victories in events such as awarding degrees to women showcase the painstaking efforts and sacrifices involved in dismantling gender barriers. This theme highlights a pivotal historical moment when societal change was both promised and fiercely contested, underscoring the courage and resilience required for women to advance in a world determined to keep them subordinate.

The Impact of War on Women’s Lives and Identities

The aftermath of the First World War profoundly shapes the characters’ experiences and emotional landscapes, illustrating how the conflict left enduring scars on both society and individuals. Many women in the story, including Dora and Otto, carry personal losses or traumas that influence their motivations and relationships.

Dora’s grief over her fiancé presumed dead, and later betrayed, underscores the precariousness of women’s emotional and social positions during wartime and its aftermath. The presence of disabled veterans, Teddy’s physical injuries, and the subtle reminders of war’s devastation infuse the narrative with a somber awareness of how the conflict reshaped traditional gender roles and expectations.

Women who had contributed to the war effort, whether as ambulance drivers, volunteers, or in other capacities, return to a society that both acknowledges their contributions and swiftly attempts to reimpose conventional norms. This creates a complex tension where women strive to assert new forms of independence and purpose but must navigate lingering societal skepticism and personal loss.

The war’s shadow affects not only external circumstances but also internal identities, prompting characters to reconsider their futures, ambitions, and the nature of their relationships. The story captures this uneasy transition from wartime upheaval to post-war reconstruction, where the promise of progress is tempered by unresolved trauma and the persistence of traditional expectations.

Friendship and Female Solidarity

Amid the challenges and hostilities the characters face, the formation of strong bonds between the women stands out as a vital source of strength and comfort. The group known as “the Eights” represents a microcosm of diverse backgrounds, personalities, and ambitions, yet they find common ground in their shared experiences of marginalization and aspiration.

Their friendship provides emotional refuge from the institutional pressures and social restrictions that surround them. Through late-night conversations, shared humor, and acts of kindness, they construct a sense of belonging and mutual support that enables them to persevere in a hostile environment.

These relationships are portrayed with nuance, showing both camaraderie and occasional tensions, reflecting the complexity of female friendships under stress. The narrative emphasizes how solidarity among women becomes a form of resistance against the loneliness and alienation imposed by patriarchal structures.

Whether it is Otto’s private negotiations to enjoy small freedoms, Marianne’s gradual integration into the group despite her initial isolation, or Beatrice’s admiration and eventual romantic feelings towards Ursula, these connections illustrate how interpersonal bonds contribute to identity formation and empowerment. This theme also gestures toward the broader feminist ideal of collective action, suggesting that personal relationships can fuel larger social change.

The Quest for Personal and Intellectual Autonomy

The pursuit of education serves as more than just academic achievement for the women in The Eights; it is a profound quest for autonomy and self-definition. Each character approaches their studies and university life with distinct motivations, reflecting different ways women sought to claim independence in a world structured against them.

Beatrice’s scholarly ambitions and political awareness, Otto’s reliance on the certainty of mathematics as a refuge from familial constraints, Marianne’s efforts to balance academic goals with family obligations, and Dora’s tragic arc highlight the tension between personal desires and external limitations. The story does not shy away from depicting the psychological toll of striving for success in a hostile environment—the humiliation, exclusion, and self-doubt that accompany these efforts.

The academic rigor, illustrated by demanding tutors and difficult examinations, mirrors the social challenges the women face. Moreover, the narrative acknowledges the limited practical prospects for women’s careers, with degrees often relegated to roles like teaching or secretarial work, underscoring the gap between educational attainment and societal acceptance of female autonomy.

Yet, the women’s determination to participate fully in academic life symbolizes their broader struggle to shape their identities and futures on their own terms. The author portrays this quest as both an individual and collective journey, where intellectual freedom becomes inseparable from political and social emancipation.

The Intersection of Class and Gender

Class distinctions subtly shape the experiences and opportunities of the female students, intertwining with the theme of gender to create complex social dynamics. Marianne’s struggles as a war widow and single mother who must hide her status to avoid stigma highlight how class and gender expectations compound difficulties for certain women.

The role of Maud, the scout who manages household tasks, also emphasizes the working-class labor supporting the lives of middle-class students, pointing to underlying class hierarchies within the supposedly progressive university setting. Differences in family backgrounds, from Beatrice’s politically active suffragette mother to Otto’s rebellious upper-middle-class family, reveal how class influences attitudes towards education, marriage, and independence.

The narrative does not idealize the women’s quest for equality but shows how class privileges and constraints shape their paths and relationships. The nuanced portrayal of these intersecting identities enriches the story’s social critique, illustrating that the fight for women’s rights was not monolithic but complicated by economic and social status.

This theme calls attention to the varied realities faced by women and the necessity of considering multiple axes of identity in understanding historical and ongoing struggles for equality.