Anima Rising Summary, Characters and Themes

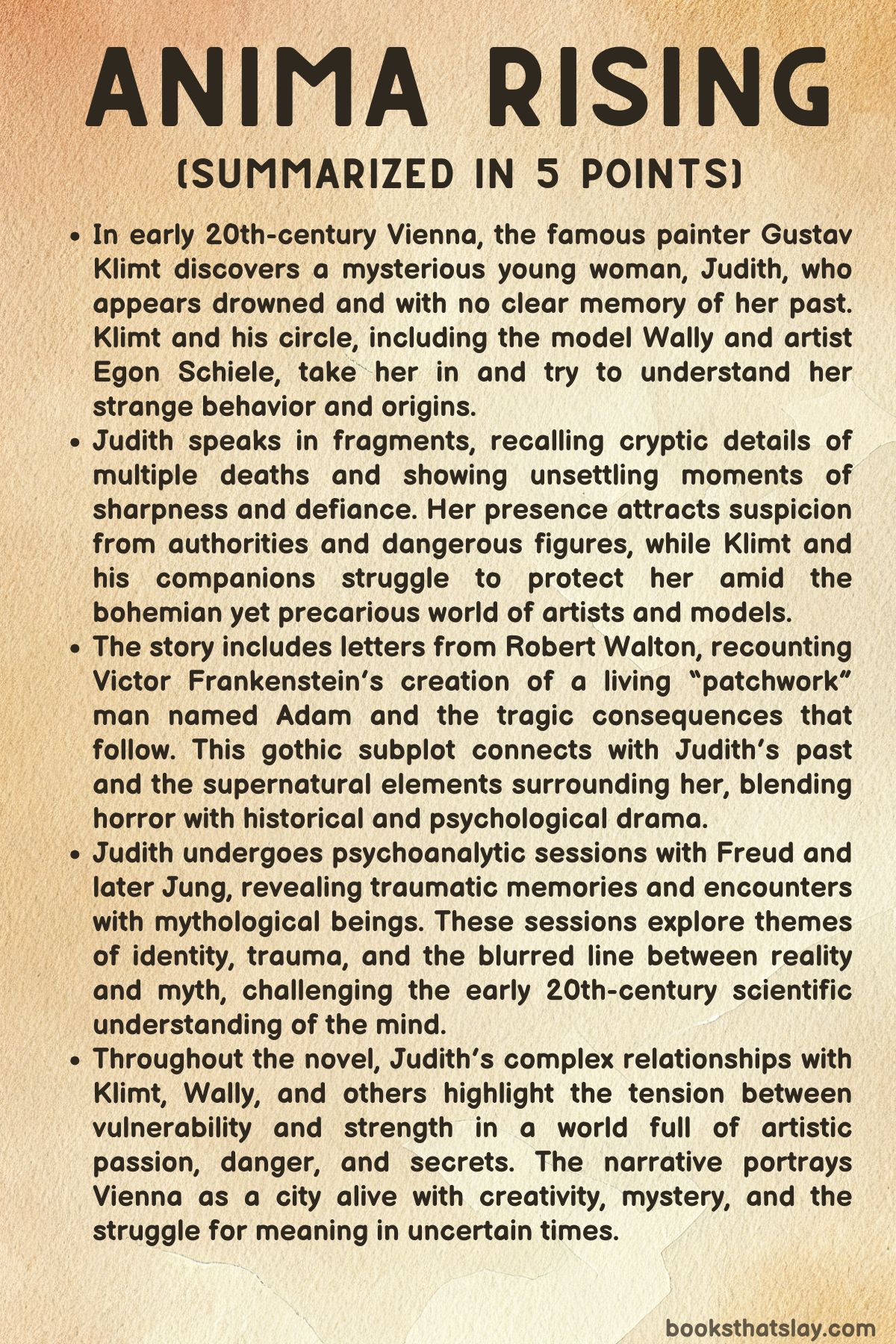

Anima Rising by Christopher Moore is a unique blend of historical fiction, gothic mystery, and supernatural fantasy set in early 20th-century Vienna. The story centers on a mysterious young woman named Judith, found drowned and seemingly lifeless in the Danube canal, who inexplicably survives and becomes the focus of a circle of famous artists, including Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele.

As Judith struggles to regain her identity, the narrative intertwines with dark, otherworldly elements connected to the Frankenstein mythos and the supernatural. This richly atmospheric tale explores themes of art, trauma, identity, and survival against a backdrop of cultural ferment and looming danger.

Summary

The story opens in Vienna with Gustav Klimt discovering a drowned girl in the Danube canal. The girl’s pale, lavender skin and ethereal presence remind Klimt of the women in his paintings.

Though she appears lifeless, she suddenly coughs and refuses medical help, compelling Klimt to rescue her. With the help of a young newsboy named Max, Klimt carefully transports her to his studio.

There, his model Wally Neuzil tends to her, and soon Egon Schiele, another artist, becomes involved. The girl, who is mute or mentally impaired, speaks only fragmented English and claims to have “died four times.” Her odd behaviors—such as building nests, scattering trout around a café, and feeding cats—cause confusion but also sympathy among those around her.

As Judith, the girl is given a name by Klimt, she reveals fragmented memories and a violent past, including her history as a prostitute in Amsterdam and episodes of killing abusive clients. Despite her disorientation, she exhibits moments of sharp wit and defiance.

Wally becomes her caretaker and protector amid the precarious realities of poverty and societal judgment in their bohemian circle. Klimt juggles his artistic commitments while grappling with Judith’s mysterious condition and the attention it draws, including from suspicious police and a threatening Dutchman linked to a headless body found in the canal.

Parallel to this, the narrative presents a letter from 1799 by Robert Walton, an English explorer who recounts rescuing Victor Frankenstein from Arctic ice. Frankenstein tells his tragic story of creating a monstrous “patchwork” man named Adam from corpse parts and animating him with lightning.

Adam learns language and society but faces rejection due to his grotesque appearance. His violent acts, including murder and kidnapping, force Frankenstein into a desperate struggle.

After destroying a female companion he had begun creating for Adam, Frankenstein faces the creature’s curse and eventual death. Walton discovers a frozen woman in a crate aboard his ship, who later awakens, connecting the gothic tale to the present-day story in Vienna.

Back in Vienna, Judith’s recovery progresses with sessions involving Sigmund Freud and later Carl Jung, who use psychoanalysis and hypnosis to explore her submerged memories. Freud explains the conscious and subconscious mind and suspects trauma as the cause of Judith’s amnesia.

Jung becomes fascinated by her descriptions of mythological figures and supernatural encounters, including her dog Geoff, who is revealed to be inhabited by a shape-shifting god named Akhlut. Judith recounts surviving multiple deaths and encounters with Arctic gods, further complicating her identity and history.

As Judith’s story unfolds, tensions rise with threats from those hunting her. A police investigation and an ambush reveal that a mysterious figure named Adam, Frankenstein’s creation, continues to cast a shadow over her life.

Judith’s lethal skills and supernatural abilities emerge, including shape-shifting and violent defense of those she cares about. The story explores Judith’s complex nature as both victim and avenger, caught between worlds of human vulnerability and divine power.

The relationships between the characters highlight the struggles within the artistic community of Vienna—Klimt’s protective yet complicated ties with his models, Wally’s fierce loyalty, and Egon Schiele’s legal troubles following the exposure of his erotic drawings. The narrative captures the precarious existence of artists balancing genius, desire, and survival amid social judgment and political tensions.

Judith’s journey takes her from Vienna to Basel, where she meets Jung and further explores the depths of her memories and powers. Jung grapples with the challenge her supernatural experiences pose to his scientific worldview, particularly in light of Freud’s disapproval.

Judith’s identity as Elspeth Lindsey, born in 1779 and bound by a mysterious immortality linked to Frankenstein’s monster, is gradually revealed through encounters with allies like Waggis, who explains her past and her connection to the supernatural.

The novel culminates with Judith embracing her shape-shifting nature and deciding to accept protection while maintaining her independence. Meanwhile, the fates of other characters intertwine: Wally trains as a nurse and reunites with Judith through a supernatural blood transfusion; Klimt faces his own mortality, depicted in a surreal afterlife where he exists as a talking squirrel cared for by Judith and her divine companions.

Set against the cultural vibrancy of early 20th-century Vienna, featuring real historical figures such as Klimt, Freud, Jung, and Schiele, the story presents a unique fusion of gothic horror, psychological drama, and fantasy. It raises profound questions about identity, creation, and the human condition while portraying a city and era on the edge of modernity.

The presence of the undead girl and her ties to Frankenstein’s mythos add layers of mystery and suspense, making the novel a complex exploration of trauma, art, and survival in a world where the boundaries between life and death, reality and myth, are blurred.

Characters

Judith

Judith stands at the heart of the narrative as a mysterious and immortal woman whose past is shrouded in darkness and supernatural complexity. Found drowned and nearly lifeless, Judith struggles with amnesia and fragmented memories, often revealing glimpses of her violent history as a prostitute in Amsterdam, where she survived and even thrived through deadly encounters with abusive clients.

Her enigmatic nature is heightened by her defiant, sometimes unsettling behavior—she oscillates between vulnerability and fierce independence, demonstrating a sharp intellect masked by confusion. Judith’s connection to mythic forces and her shape-shifting abilities blur the line between human and divine, positioning her as a liminal figure caught between life and death, reality and myth.

Her loyalty to those who protect her, combined with a readiness to confront threats with lethal force, makes her both a muse and a dangerous enigma. Throughout the story, Judith grapples with the trauma of her past, her multiple deaths and rebirths, and the haunting presence of Adam—the monstrous creation from the Frankenstein mythos—who relentlessly pursues her.

Her identity as Elspeth Lindsey and her survival through centuries reinforce themes of immortality and transformation, making her a powerful symbol of resilience and the uncanny.

Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt is portrayed as the renowned painter deeply entrenched in the bohemian artistic culture of early 20th-century Vienna. Klimt is both a protector and a patron, taking responsibility for Judith after her discovery in the canal and attempting to shield her from external dangers.

His relationships with his models, particularly Wally and Judith, reveal a complex dynamic of care, artistic inspiration, and social navigation in a world where poverty and judgment coexist with creative passion. Klimt’s character embodies the tension between artistic genius and human vulnerability, often overwhelmed by the chaotic realities around him—from Egon Schiele’s arrest to the supernatural and criminal threats linked to Judith.

His interaction with historical figures such as Freud and Jung situates him within the intellectual ferment of Vienna, while his compassion and occasional humor offer warmth amid the darker elements of the narrative. Klimt’s eventual death and transformation into a talking squirrel in the Underworld add a surreal, mythic layer to his character, underscoring the story’s blend of history and fantasy.

Wally Neuzil

Wally is Klimt’s devoted model and caretaker figure who stands out for her pragmatic strength and fierce loyalty. She assumes responsibility for Judith’s wellbeing, even at personal cost—such as when she risks injury attempting to break Egon Schiele out of jail.

Wally’s grounding presence provides stability amid the chaos, offering Judith practical support and emotional steadiness. Despite her own precarious position as a model and part of the bohemian scene, Wally navigates the complexities of poverty, social stigma, and friendship with determination.

Her pragmatic nature contrasts with Judith’s enigmatic and sometimes volatile persona, making her a crucial anchor for both Judith and Klimt. Wally’s role extends beyond that of a mere caretaker; she embodies the struggles and resilience of women in an era marked by artistic freedom and societal limitations.

Egon Schiele

Egon Schiele, depicted as a younger, provocative artist closely linked to Klimt’s circle, represents the raw, often controversial edge of Viennese modernism. His arrest for exposing erotic drawings to children exemplifies the precarious balance artists maintain between creative expression and societal repression.

Schiele’s presence injects tension and urgency into the narrative, as his fate intertwines with the broader themes of art, censorship, and rebellion. His relationship with Wally and Klimt highlights the interconnectedness of this artistic community, where personal and professional lives overlap in complicated ways.

Schiele’s youthful intensity and brushes with the law underscore the risks artists faced in a conservative society on the brink of modernity.

Max

Max is a young newsboy who assists Klimt in rescuing and transporting the drowned girl. Though a minor figure, Max represents the innocence and resourcefulness of Vienna’s lower social strata.

His involvement in the initial stages of Judith’s recovery ties him to the larger narrative of survival and care. Max’s presence illustrates the intersection of different social classes within the artistic and bohemian milieus of the city, providing a glimpse into the everyday life surrounding the central characters.

Victor Frankenstein and Adam

Though not part of the Viennese setting, Victor Frankenstein and his creation Adam are essential characters introduced through the letters of Robert Walton. Frankenstein embodies the archetype of the tragic scientist whose quest to transcend natural limits unleashes catastrophic consequences.

His story—marked by obsession, creation, destruction, and regret—parallels the gothic and supernatural themes running through Judith’s tale. Adam, the “patchwork” man, is a figure of alienation and monstrous otherness, whose violent actions drive much of the horror underpinning the narrative.

His demand for a companion and subsequent vengeance create a chilling backdrop that informs Judith’s own experiences with pursuit, survival, and identity. The integration of Frankenstein’s mythos links the novel’s exploration of creation, humanity, and monstrosity to Judith’s mysterious existence and the broader questions about life and death.

Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung

Freud and Jung appear as historical figures engaging with Judith’s psychological state, grounding the supernatural elements in contemporary psychoanalytic theory. Freud’s attempts to unlock Judith’s trauma through free association highlight the tension between science and the uncanny, while Jung’s exploration of the collective unconscious and archetypes opens the narrative to mythological dimensions.

Their contrasting approaches reflect the era’s intellectual ferment and serve as narrative devices to deepen Judith’s character and the story’s themes of memory, identity, and trauma. The involvement of these figures also situates the story within the cultural milieu of Vienna, linking its gothic mystery to real-world developments in psychology.

Emilie Flöge

Emilie is portrayed as a powerful, enigmatic fashion designer and companion to Klimt, representing the modern woman navigating artistic and social spheres with grace and influence. Her introduction of music into the plein air sessions and her support for the artists reveal her role as a muse and facilitator within the creative community.

Emilie embodies a balance of strength, optimism, and practicality that contrasts with the more chaotic lives of the models and painters, adding depth to the social fabric depicted in the story.

Judith’s Dog Geoff (Akhlut)

Geoff is more than a pet; he is inhabited by the god Akhlut, a shape-shifting protector who accompanies Judith between worlds. This supernatural aspect enriches the novel’s mythology, emphasizing Judith’s liminal existence and the fusion of divine and earthly elements.

Geoff’s fierce loyalty and intervention in violent encounters illustrate the protective forces surrounding Judith and contribute to the story’s blending of myth, fantasy, and reality.

Waggis

Waggis appears as a mysterious figure who reveals crucial truths about Judith’s identity and past. He connects her to her origins in Northumberland and the Arctic, shedding light on her immortality and entanglement with Adam.

Waggis functions as both guide and protector, inviting Judith to embrace her complex legacy. His presence deepens the narrative’s mythic structure and expands Judith’s story beyond Vienna to a wider, supernatural context.

Themes

Identity and Memory

The fluidity and fragmentation of identity take center stage in Anima Rising through the character of Judith, whose mysterious origins and lost memories create a continuous tension throughout the narrative. Judith’s amnesia and her inability to recall her past leave her caught in a liminal state between who she was, who she is, and who she might become.

This struggle with selfhood is complicated by her supernatural longevity and experiences of repeated death and resurrection, challenging conventional ideas of a fixed, linear identity. Her fragmented speech, scattered memories, and moments of defiance highlight how trauma—both psychological and possibly supernatural—can disrupt personal coherence, making identity a contested and evolving terrain rather than a settled fact.

The psychoanalytic sessions with Freud and later Jung emphasize the complexity of uncovering the layers beneath conscious awareness, exposing how repression, violence, and mythology intermingle in Judith’s psyche. The book probes the tension between societal naming and labeling, as seen when Klimt renames her “Judith,” and her own refusal to be fully owned or defined by others.

Judith’s identity becomes a battleground where personal history, mythology, and the creative acts of naming and interpretation collide, illustrating the difficulty of reclaiming one’s self amid disorientation and external pressures. This theme explores how memory shapes identity, but also how identity can resist memory and explanation, leaving space for mystery, power, and transformation.

Creation, Art, and the Role of the Artist

The novel situates early 20th-century Vienna’s vibrant artistic milieu as both a backdrop and an active force in the story, presenting creation as a complex, often fraught process that extends beyond the canvas into life itself. Klimt, Schiele, and other artists embody the tension between beauty and chaos, order and disruption, as they navigate poverty, social scrutiny, and personal demons while producing iconic works.

Klimt’s fascination with the drowned girl, whose pale lavender skin evokes his paintings, reveals how art blurs the boundary between reality and imagination, life and death. The artists’ bohemian lifestyle, replete with moments of humor, tenderness, and scandal, reflects how artistic creation is inseparable from the messy realities of human relationships and social marginalization.

The story also echoes the gothic theme of creation through the Frankenstein subplot, posing questions about the ethical limits of scientific and artistic creation, the consequences of playing god, and the loneliness that accompanies being a creator. Adam, Frankenstein’s “patchwork” man, and the undead girl evoke the idea that creating life—whether through science or art—is both a powerful and perilous act that can alienate the creator from their creation and from society.

Thus, creation emerges not simply as an act of beauty but as a fraught, sometimes violent negotiation with mortality, otherness, and responsibility.

Trauma and Survival

Trauma, both physical and psychological, shapes much of the novel’s emotional and narrative landscape, illustrating the brutal realities faced by Judith and those around her. Judith’s past as a prostitute involved in violent confrontations with abusive men, her experiences of repeated death and resurrection, and her encounters with supernatural entities combine to create a portrait of survival against overwhelming odds.

The presence of trauma also manifests in the cultural and social context of fin-de-siècle Vienna, where poverty, exploitation, and societal judgment coexist with intellectual and artistic innovation. Judith’s erratic behavior, moments of violence, and psychological fragmentation are expressions of trauma’s lingering effects, while her refusal to be victimized conveys a fierce will to survive.

The use of psychoanalysis in the narrative—Freud and Jung’s attempts to unlock her subconscious—illustrates the search for understanding trauma’s roots and its impact on identity and behavior. The motif of survival extends beyond Judith to the artistic community, which grapples with societal rejection, censorship, and existential doubt.

The theme examines the resilience required to live and create amid trauma, showing how survival is not only a physical endurance but also an ongoing psychological and spiritual struggle.

Mythology, the Supernatural, and the Collective Unconscious

The novel incorporates mythology and supernatural elements to challenge and expand the boundaries of reality, blending folklore, gothic horror, and psychological theory. Judith’s narrative is steeped in mythic symbolism, with references to Arctic gods like Raven and Sedna, shape-shifting abilities, and a divine dog companion, Geoff, inhabited by a god named Akhlut.

These mythological elements underscore a larger theme about humanity’s connection to archetypes and ancient stories, which Carl Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious highlights. Jung’s fascination with Judith’s experiences as manifestations of shared mythic patterns challenges Freud’s more rigid scientific worldview, opening the story to interpretations that transcend empirical reality.

The supernatural aspects complicate Judith’s identity, positioning her as a liminal figure straddling human and divine realms, life and death, history and myth. This theme explores how myth and supernatural belief serve as frameworks for understanding trauma, identity, and power, suggesting that beneath the surface of modern scientific rationalism lies a vast, often hidden world of symbols and forces shaping human experience.

It also raises questions about the nature of reality itself, inviting readers to consider the coexistence of multiple truths within a single narrative.

Power, Exploitation, and Societal Marginalization

The social dynamics of early 20th-century Vienna, as depicted in the novel, reveal harsh realities of power imbalances, exploitation, and marginalization within artistic and lower-class communities. Judith’s background as a prostitute and her violent resistance against abusive men illuminate the precarious existence of women in a society that frequently objectifies and oppresses them.

Klimt’s protective but sometimes paternalistic relationships with his models highlight the complex interplay of care, control, and survival within bohemian circles, where artistic genius often masks social inequality. The threat posed by the Dutch investigator, the shadowy henchmen, and the police underscore the constant danger faced by marginalized individuals who defy social norms or who carry dangerous secrets.

The imprisonment of Egon Schiele for alleged corruption of minors reflects broader societal fears and the ways institutions police and punish those who transgress. Throughout the narrative, characters navigate a world that both romanticizes artistic freedom and enforces rigid boundaries of class, gender, and morality.

This theme exposes the contradictions of a society in flux—caught between enlightenment ideals and entrenched injustices—and highlights how survival and resistance often require subversion, solidarity, and sometimes violence.

Life, Death, and Immortality

The narrative continuously interrogates the boundaries between life and death, especially through Judith’s multiple deaths and resurrections and the presence of Frankenstein’s undead creations. Judith’s undead status complicates traditional understandings of mortality, placing her in a unique space where she experiences life beyond natural limits but also endures profound alienation and danger.

The Gothic elements of the story—frozen landscapes, headless bodies, reanimated corpses—symbolize the persistent human fascination with overcoming death and the moral and existential dilemmas that arise from it. The tension between the desire for immortality and the consequences of defying natural cycles raises questions about the cost of eternal life, including loss of identity, perpetual trauma, and endless conflict.

The presence of supernatural beings and gods further complicates these themes by introducing alternate forms of existence that challenge human-centered definitions of life and death. Ultimately, the novel suggests that immortality is not a simple gift but a complex, often tragic condition intertwined with memory, identity, and the quest for meaning in an impermanent world.