The Summer We Ran Summary, Characters and Themes

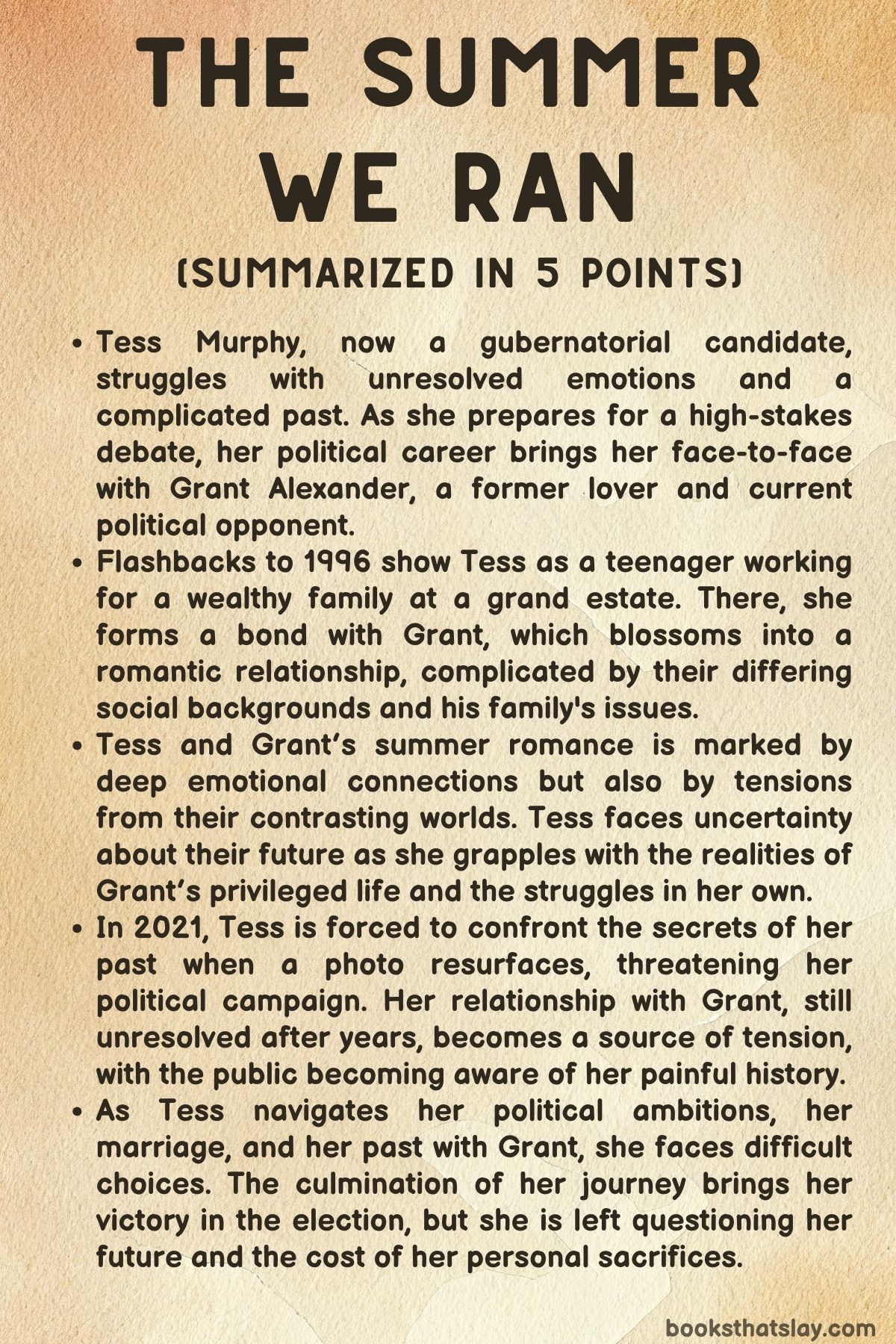

The Summer We Ran by Audrey Ingram is a novel that explores love, loss, and the complexity of relationships, blending past and present as the protagonist navigates both personal and political struggles. The story follows Tess Murphy, a woman running for governor, who finds herself caught in the tension between her ambitions and her unresolved past.

Throughout the narrative, Tess confronts long-buried memories, particularly a tumultuous romance with her political rival, Grant Alexander. As the election nears, the emotional weight of Tess’s earlier choices and relationships threatens to unravel her carefully constructed life. This thought-provoking book delves into identity, trust, and the choices that shape our futures.

Summary

The novel begins in January 1997, with Tess Murphy lying in a hospital bed, grieving the loss of someone she deeply cared about. Her mother tries to comfort her, but Tess feels broken and unable to express her profound sorrow.

The weight of her emotions leaves her feeling lost, and she whispers that the person she lost was a part of her. Despite the grief, Tess understands she must continue living, even as the pain overwhelms her.

The story then transitions to June 2021, where Tess, now an adult, is preparing for a gubernatorial debate in Virginia. She receives a campaign paper at home and nervously looks at a photo of herself and her opponent, Grant Alexander.

The picture stirs uncomfortable memories of their past, and Tess feels uneasy about facing Grant once more. Her husband, Dean, jokes about life after her potential victory, but Tess is distracted by the emotional weight of her past with Grant, which she has kept hidden for years.

The narrative shifts back to June 1996, when Tess, a 17-year-old, is discontent with her life. She and her mother are on a long drive to an estate where Tess’s mother has secured a job as a house manager.

Tess’s mother is hopeful that this job will bring stability and a fresh start, but Tess feels out of place in the luxurious setting of the estate, which starkly contrasts with their modest life. Tess struggles with the social divide between the grand estate and the life she has known.

Upon their arrival, Tess is introduced to the wealthy and eccentric residents of the estate, including Kay Alexander, whose son, Grant, will play a pivotal role in Tess’s life.

Tess’s mother begins working at the estate, and Tess is left to fill her summer with activities. She meets Grant, a charismatic and confident boy who is comfortable in the world of privilege.

Tess, on the other hand, feels awkward and out of place. Despite their differences, the two start to form a bond.

Over time, Tess becomes more at ease in Grant’s world, although she is constantly aware of their differing backgrounds. Their relationship grows deeper, and Tess experiences her first true romantic feelings.

As the summer unfolds, the bond between Tess and Grant deepens, but Tess becomes increasingly aware of the social divide between them. Grant’s family background is one of wealth and privilege, and Tess, who has always felt uncomfortable with her humble upbringing, finds herself caught between two worlds.

While Tess struggles with her feelings for Grant, she also discovers that his family life is far from perfect. Tensions exist between his parents, and despite their growing closeness, Tess realizes that their worlds may never truly align.

In June 2021, Tess is a political figure, preparing for a tight gubernatorial race. She finds herself facing Grant, who is also running for governor as the Republican candidate.

Their shared past remains a secret, but as the election approaches, it becomes impossible for Tess to keep her history with Grant hidden. In a private moment before their debate, Tess and Grant confront the painful truths of their past.

Although they agree to leave their history behind for the sake of the campaign, the emotional tension between them remains strong. As the debate begins, Tess and Grant exchange political jabs, but Tess cannot shake the feeling that their shared history may soon be exposed, potentially ruining both their careers.

Tess struggles to deal with the emotional turmoil of reconnecting with Grant after all these years. Though they are rivals in the political arena, the unresolved emotions from their past complicate her focus on the campaign.

Tess begins to understand that the unresolved issues between them could impact both her political career and her marriage.

In July 2021, Tess unexpectedly returns home to find her husband, Dean, participating in a photo shoot for her campaign, something he strongly dislikes. Dean reluctantly participates in the shoot, and Tess becomes frustrated by the intrusion into their personal space.

As Tess reflects on her campaign, she realizes that the grueling schedule has put a strain on her relationship with Dean. Despite their once happy life together, Tess begins to fear that her political ambitions are damaging their connection.

Flashbacks to Tess’s earlier years provide further insight into her personal life. In the summer of 1996, Tess works at Kay Alexander’s estate, which exposes her to a world of wealth and privilege.

While helping around the estate, Tess becomes closer to Grant, who confides in her about his strained relationship with his father. Tess notices increasing tension between Kay and Richard, Grant’s father, whose controlling and abusive behavior becomes evident.

Despite her growing feelings for Grant, Tess is uncertain about their future. Their relationship becomes more complicated as Tess navigates her feelings for Grant and the challenges posed by their differing backgrounds.

Characters

Tess Murphy

Tess Murphy is the central figure of The Summer We Ran, and her journey spans both adolescence and adulthood, weaving together her political ambition and her personal struggles. As a teenager, Tess grapples with feelings of displacement when she and her mother move into the wealthy Alexander estate.

She is uncomfortable with the stark divide between her humble background and the privilege that surrounds her, yet she cannot resist the pull of Grant Alexander, whose charm and vulnerability awaken her first experiences of love. Tess is shaped by this summer of discovery, her sense of identity challenged by the contrast between who she is and who she might become.

In adulthood, Tess has grown into a strong, ambitious woman, running for governor of Virginia. Her political career is marked by determination and a drive to succeed, but her carefully constructed image is threatened by the reemergence of Grant, who embodies her unresolved past.

Her marriage to Dean reveals another layer of Tess’s complexity, as her ambition strains her relationship, forcing her to confront the balance between personal fulfillment and professional success. Tess’s character embodies resilience, vulnerability, and the enduring impact of formative choices.

Grant Alexander

Grant Alexander represents both Tess’s greatest youthful passion and her most challenging rival. In 1996, Grant is portrayed as charismatic and confident, someone deeply comfortable in his privileged world.

Yet beneath his polished exterior lies discontent, born from his fractured relationship with his domineering father. His growing bond with Tess allows him moments of honesty and vulnerability, and their romance is as much about escape from his family’s expectations as it is about young love.

Decades later, Grant reappears as Tess’s political opponent, their private history colliding with the public arena. He is a complex figure, embodying both nostalgia and tension, a reminder of Tess’s past and a threat to her future.

While he outwardly projects strength as a political candidate, his interactions with Tess reveal lingering emotions and unresolved conflicts, highlighting the duality of a man torn between power and memory.

Dean Murphy

Dean, Tess’s husband, provides a grounding presence in her adult life, yet his role is complicated by the demands of her political career. He is portrayed as supportive, though somewhat reluctant, especially when her campaign intrudes into their private space, as shown during the photo shoot he resents participating in.

Dean’s discomfort reveals the strain that Tess’s ambitions place on their marriage, exposing the sacrifices and adjustments required in a partnership where one person’s public life overshadows domestic stability. His love for Tess is evident, but his frustrations hint at fissures in their relationship, making him both a source of comfort and a symbol of the costs of ambition.

Kay and Richard Alexander

Kay Alexander, Grant’s mother, introduces Tess to the world of privilege that defines the estate. She appears eccentric and somewhat removed, a woman navigating her own tensions within a fractured marriage.

Her presence highlights the contrast between wealth and dysfunction, showing that luxury does not protect against emotional strain. Richard Alexander, Grant’s father, represents the darker side of privilege, exerting control and displaying abusive tendencies.

His strained relationship with Grant exposes the cracks in the family’s polished exterior, reinforcing the idea that power and wealth often conceal deep personal turmoil. Together, Kay and Richard provide the backdrop against which Tess and Grant’s bond is formed, shaping both the allure and the challenges of their summer relationship.

Themes

Love, Loss, and Grief

Grief stands as the quiet engine of The Summer We Ran, shaping Tess Murphy’s choices long before voters or headlines do. The opening image—Tess in a hospital bed in January 1997, unable to voice the degree of her sorrow—establishes loss as both a private catastrophe and a formative event that refuses to stay tucked away.

This isn’t a single bereavement neatly processed; it is a wound that informs Tess’s sense of responsibility, survival, and attachment. As the narrative moves forward to 2021, that early sorrow shadows her marriage to Dean and her wary reunion with Grant Alexander, charging every political calculation with emotional residue.

Love, then, is not simply romantic memory between Tess and Grant; it is a force tested by class difference, by youthful uncertainty, and by the mature demands of public life. The novel treats first love as a site of risk and self-definition, where tenderness collides with unequal power and social position.

Grief consequently becomes a measure of authenticity: how a person grieves signals what they value, whom they trust, and what they are willing to sacrifice. Tess’s difficulty articulating the loss in her youth echoes in her later struggle to speak truthfully about her history with Grant, suggesting that unexpressed pain hardens into secrecy.

The gubernatorial campaign tries to standardize emotion—family photos, tidy talking points—yet the book insists that sorrow resists branding. In that resistance, grief paradoxically offers clarity.

It asks Tess to identify what matters when the pose of competence falters: love as care rather than spectacle, loyalty rather than optics, and memory as obligation rather than nostalgia.

Ambition and the Cost of Leadership

Political ambition in The Summer We Ran is not glamorized; it is shown as a continuous negotiation with fatigue, compromise, and the erosion of privacy. Tess’s campaign schedule strains her relationship with Dean, and even the seemingly harmless campaign photo shoot intrudes on their household, turning home into a set.

The novel underscores how ambition demands choreography—debate prep, message discipline, coordinated appearances—yet that choreography cannot protect against the unpredictability of human feeling or the resurfacing of the past. Tess’s desire to govern is sincere, but sincerity does not cancel out the trade-offs required to win.

The campaign forces her to rank values: protecting her marriage, telling the whole truth about her past, respecting her own boundaries, and confronting a rival who was once a lover. The book also pays attention to gendered expectations.

As a woman running for governor, Tess contends with judgments about likability, toughness, and propriety that filter not only her policies but her personal history. Ambition, then, takes on a double cost: she must be better than her opponent on the merits while also being cleaner in biography, calmer in demeanor, and self-erasing when necessary.

The private exchange with Grant before the debate exposes the limits of political performance; some conflicts cannot be neutralized by strategic silence. The closer the election draws, the more ambition looks like endurance rather than aspiration—a daily question of how much of oneself must be given up to secure a public mandate.

By refusing to separate the campaign from the home, the narrative argues that leadership has a price best measured in emotional currency: trust spent, patience drained, intimacy postponed.

Memory, Time, and the Stories We Tell Ourselves

The novel’s movement between 1996, 1997, and 2021 presents memory not as a gentle recall but as active terrain where identity is contested. In The Summer We Ran, memory carries weight because it is politically dangerous and personally inescapable.

Tess’s summer at the Alexander estate is not a scrapbook; it is a living file that the present keeps reopening. The past is constructed through feelings—awkwardness about class, first attraction, fear of exposure—just as much as through events.

By staging the narrative across decades, the book shows how choices that once felt private become public artifacts once a candidacy begins. Memory is also unreliable in productive ways: Tess’s recollection is colored by age, shame, and longing, which means the truth is something she must continually earn rather than simply retrieve.

The hospital scene operates like a watermark on every later page, reminding readers that grief distorts time, slowing it down, repeating it, and making certain days louder than others. The 2021 debate preparations further expose how campaigns attempt to fix the past into a single line in a biography, while life resists summary.

Grant’s presence is a test of Tess’s narrative control; he remembers with his own biases and needs. The result is a meditation on whether one can meaningfully move forward without risking the full story.

Memory in the novel is less about nostalgia than accountability. It asks: Which parts of our former selves do we claim, which do we hide, and what is the ethical obligation of a leader to own the origins of her convictions?

Class, Privilege, and Belonging

From the moment Tess arrives at the opulent estate where her mother works, class difference becomes a structural force shaping desire, embarrassment, and possibility. The Summer We Ran places a young woman from a modest background in a space calibrated to center wealth, making every interaction with Grant double-coded: romantic interest on the surface, social education underneath.

Tess learns the informal rules of privilege—the ease with which Grant moves, the assumption of welcome, the expectation that comfort is the norm—and she learns how those rules make other lives feel provisional. Her sense of being out of place is not solely internal; the setting is designed to affirm some people and quietly instruct others to feel grateful for access.

This dynamic complicates her first love. Attraction is real, but so is the friction that comes from knowing the relationship operates across asymmetries of money, reputation, and family power.

The novel also suggests how class shapes risk. For Grant, mistakes may be absorbed by resources or reputation; for Tess, a similar misstep can brand her permanently.

When she later runs for governor, the earlier class gap resurfaces in subtler form. Expectations about a candidate’s background and manner become coded tests of credibility.

Voters and media often treat polished origin stories as proof of merit, but the book reminds us that polish is often a product of insulation. Belonging, then, is never only emotional; it is institutional and material.

Tess’s adult composure reads as earned, not inherited, and the narrative insists that ambition from the margins requires different muscles: vigilance, translation across worlds, and the courage to admit when comfort has been mistaken for character.

Power, Control, and Abuse

Richard Alexander’s controlling, sometimes abusive behavior is not a subplot; it is a lens for reading how harm operates within families and how that harm echoes into public life. In The Summer We Ran, the estate is both sanctuary and stage, a place where wealth can disguise coercion as order.

Tess’s gradual awareness of the tension between Kay and Richard teaches her that power does not require shouting when property, reputation, and social standing can do the work silently. Grant’s confiding about his father’s pressure reveals how abuse can travel through expectations and legacies, shaping a son who must perform strength even while he is constrained by it.

This is crucial for understanding the adult political rivalry: Grant’s confidence often reads as fluency in systems designed for him, but it may also be survivorship masked as charm. Tess witnesses how control narrows choices, especially for women who must manage appearances to remain safe.

That knowledge later informs her caution about what to reveal during the campaign. The novel then broadens the question: if a candidate has been formed in proximity to coercive power, what responsibilities follow when seeking public authority?

It is not a call for confession for its own sake; it is an argument that leadership requires an unblinking understanding of harm and its disguises. The private dynamics at the estate become training ground for reading domination in civic forms—who sets the rules, who is excused, who pays the price when decorum is prioritized over truth.

By juxtaposing household control with statewide ambition, the book suggests that the ethics of power start at home and radiate outward.

Identity, Secrecy, and the Cost of Truth

Public identity in The Summer We Ran is a composite of policies, presentation, and strategic silence. Tess’s career has taught her that voters accept a curated story more readily than a complicated one, yet her private history with Grant keeps pressing against that curation.

Secrecy becomes both shield and trap. It protects a marriage already stressed by campaigning, and it forestalls sensationalism in the press; at the same time, it fractures Tess’s interior life, asking her to split the woman who remembers from the woman who persuades.

The pre-debate conversation with Grant shows how secrets bind even when they aim to sever: an agreement to leave the past behind still carries the intimacy of shared knowledge. The novel examines the cost of carrying such knowledge while performing transparency.

Candidates are expected to be authentic yet punishably so, a contradiction that incentivizes omission. Dean’s discomfort with the photo shoot underscores another angle: the people around a public figure are drafted into the performance, their preferences and boundaries subordinated to the campaign’s narrative needs.

Truth, then, is not a single reveal but an ongoing practice—what to say, when, and why. The book favors a moral framework in which truth-telling is measured by care: care for oneself, for the partner who did not choose the podium, for the citizens who must evaluate a leader’s character without voyeurism.

Tess’s journey suggests that sustainable identity depends on alignment between the voice onstage and the voice in private, not perfect overlap but honest proximity. The risk of exposure is real, but the risk of compartmentalization—the slow erosion of self—is greater.

The Personal and the Political

The campaign’s central conflict—Tess and Grant vying for the governor’s office while carrying a shared past—insists that personal experience does not sit outside political life but supplies its motives and blind spots. In The Summer We Ran, policy differences are important, yet the narrative keeps returning to how character is formed by relationships, grief, and unequal structures.

Tess’s early immersion in wealth she did not possess teaches her to recognize soft power and its exclusions; that recognition informs how she understands governance as more than laws—public services must account for the quiet ways dignity is granted or denied. Her grief in 1997 sharpens her sense that the state meets people at their worst moments, so compassion is not a sentiment but a design principle.

The secrecy around her past with Grant exposes the temptations of expedient storytelling in politics, where privacy can be misread as deceit and disclosure as manipulation. The novel resists cynicism by showing that the stakes of public decisions are carried home: a marriage under strain, a household under scrutiny, a candidate who must rest yet cannot.

By making the debate stage and the family kitchen contiguous spaces, the book argues that leadership is the art of moral consistency across contexts. Tess’s task is not only to defeat an opponent but to decide what kind of authority she will embody—one that replicates the pressures she once witnessed or one that answers them with accountability.

The personal is political here because the habits of attention, empathy, and courage formed in private are precisely the habits citizens will experience once the election is over.