The Entirely True Story of the Fantastical Mesmerist Nora Grey Summary, Characters and Themes

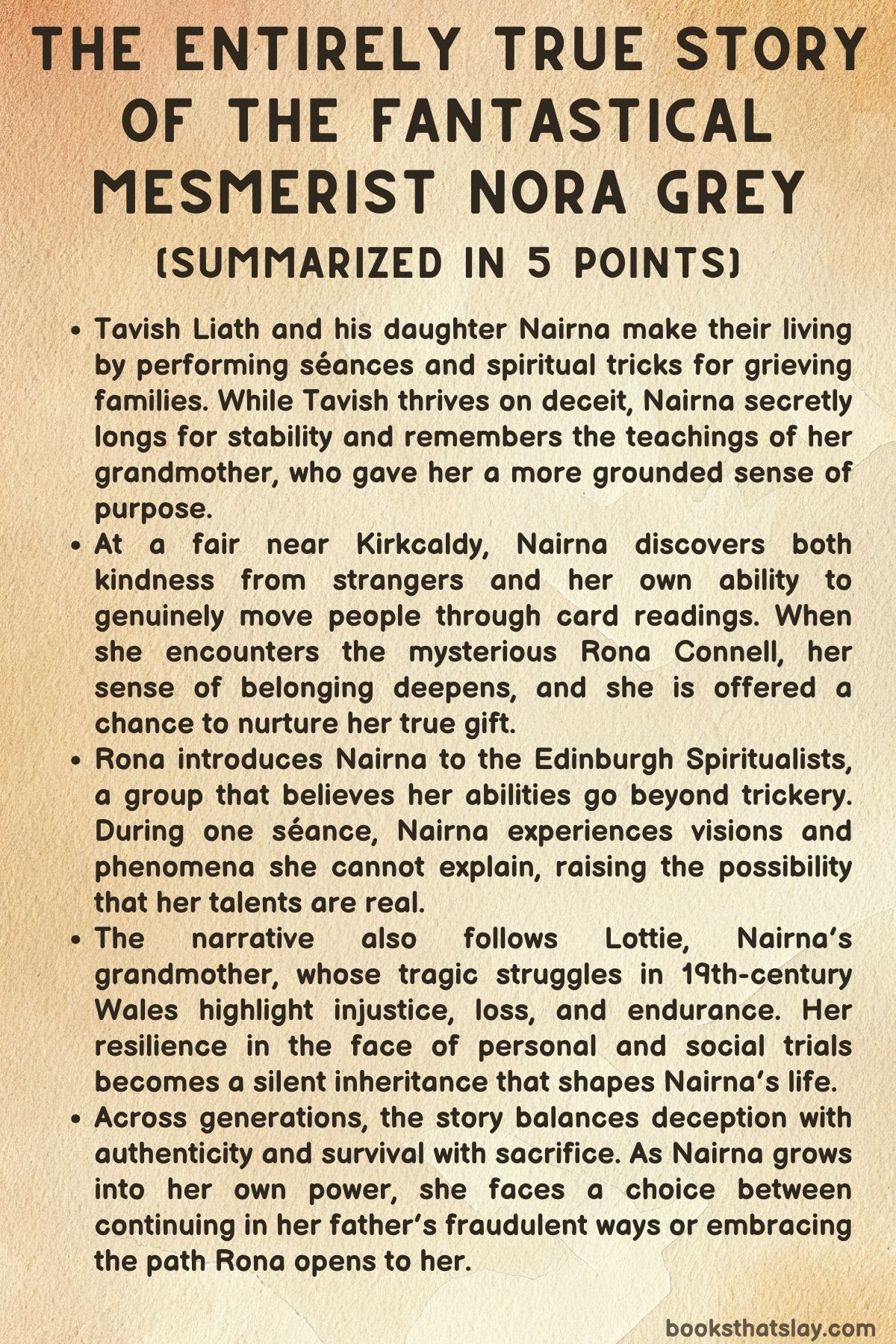

The Entirely True Story of the Fantastical Mesmerist Nora Grey by Kathleen Kaufman is a historical novel that blends folklore, spiritualism, and the struggles of women across generations. The story follows young Nairna, who is bound to her father’s schemes of false séances, until she discovers her own genuine psychic abilities and is drawn into the world of spiritualist circles.

Parallel to her story runs the life of her grandmother, Lottie, whose tragic fate in an asylum reverberates through time. Kaufman intertwines themes of exploitation, survival, and inheritance of power, exploring how grief, resilience, and mysticism shape identities across decades.

Summary

The novel opens with Tavish Liath and his daughter Nairna performing a séance for Lord and Lady Lennox, who mourn their daughter Maggie. Tavish uses rough Gaelic chanting while Nairna creates noises and illusions to simulate spirit contact.

The Lennoxes pay reluctantly, leaving Tavish bitter and Nairna exhausted. On the road to a harvest fair near Kirkcaldy, Nairna reflects on her father’s life of scams, her grandmother Nan’s teachings of card reading, and her own longing for stability.

At the fair, she finds comfort in the kindness of Wyn and her family, though she hides this from Tavish. Soon, she begins giving card readings, including one for a mysterious woman named Rona Connell.

Rona shows unusual insight, reading Nairna’s cards herself, and hints that she could help guide her gifts.

Later, Rona and her husband invite Tavish and Nairna to a séance at their home. As Tavish sets up tricks, Nairna unexpectedly sees an apparition who whispers “Enough,” shaking her deeply.

Afterward, Rona reveals the séance was a test arranged by her spiritualist circle in Edinburgh. They want Nairna, not Tavish, to join them.

For the first time, Nairna is offered a chance to separate from her father’s fraud and embrace her true powers.

Parallel to this thread runs the story of Nairna’s grandmother, Lottie. In 1866, Lottie’s husband Elis dies in a mining accident, leaving her pregnant and destitute.

When she demands fair compensation from mine owner Mr. Glasscock, he mocks her heritage and offers only a week’s wages.

Enraged, she strikes him with an ashtray, leading to her arrest. Drugged and accused of hysteria, she is sent to Argoll Asylum instead of prison.

There, under the control of Dr. Bothelli and Dr. Franz Soekan, she undergoes mesmerism and cruel experiments. Her visions show alternate realities, ghostly children, and a black-haired girl who seems connected to her descendants.

Lottie realizes her suffering fuels the doctors’ theories about psychic phenomena, yet she clings to her visions as her only escape.

Meanwhile, in Edinburgh, Nairna thrives under Rona’s mentorship. She gains fame among wealthy clients for her card readings and later astonishes audiences by levitating during séances.

Her father Tavish, increasingly sidelined, resents her independence. Nairna meets Dr. Edwin Harrison, who explains that she may be a rare physical medium capable of extraordinary phenomena. He draws comparisons to Countess Carolina Gustav, who was rumored to resurrect life.

Though wary, Nairna begins to accept that her powers extend far beyond illusions.

Another narrative layer introduces Dr. Rodney Naandaro of the International Psychical Society in 1911, who investigates a haunting at Argoll Downs.

Locals speak of the “wailing woman,” a ghostly figure connected to Lottie’s tragic fate. This haunting reflects the enduring echo of Lottie’s suffering, woven into the legends of the land.

As the story moves forward, Nora Grey—Nairna grown older—is seen performing in Boston in 1901. Under the guidance of her handler Karl Mendis, she astonishes audiences by levitating furniture during a séance, but she also admits her fear of losing control over her powers.

In Boston, she reunites with Dorothy Kellings, the celebrated medium known as the Scarlet Sunbird. Dorothy warns Nora that she must embrace her spirit guide—the black-haired woman who has long appeared in her visions—if she hopes to master her gift.

During a séance in Salem, Nora’s abilities reach a terrifying climax. She is transported across time into Lottie’s cell at Argoll Asylum, where she aids her dying ancestor in giving birth to a son, Tavish.

Initially stillborn, the child is revived through Nora’s desperate intervention across time. Lottie dies soon after, and her spirit becomes the Wailing Woman, haunting Argoll Downs.

Back in Salem, witnesses are stunned, newspapers spread sensational accounts, and Nora collapses under the strain.

Following this revelation, Sister Therese of Argoll uncovers Lottie’s true suffering and secretly ensures her body is buried with dignity. Furious at Soekan’s cruelty, she and Sister Mary orchestrate his death, turning the asylum into a place of healing rather than torment.

Dr. Bothelli fulfills his promise to deliver Tavish to an orphanage, unknowingly setting in motion the lineage that connects Lottie, Nairna, and Nora.

In 1902, weary of exploitation and spectacle, Nora decides to end her public career. She conducts a final séance with only a handful of witnesses, reaching back once more to communicate with Sister Therese.

Through this act, she secures recognition of Lottie’s suffering and a measure of justice. Soon after, Nora retreats into obscurity under the protection of Lady Loreana Bell, vanishing from public life while speculation about her fate runs wild.

Tavish remains behind, quietly continuing his life, while Nora embraces secrecy and independence.

By the novel’s end, the intertwined fates of Lottie, Nairna, and Nora illuminate a story of inheritance, resilience, and the struggle of women to claim control of their lives and powers in a world eager to exploit them. Lottie’s tragedy gives rise to legend, Nairna discovers her true calling, and Nora chooses her own path of freedom.

Through these connected lives, Kaufman explores the cost of survival, the weight of legacy, and the enduring presence of the unseen world.

Characters

Nairna Liath

Nairna is the central figure of The Entirely True Story of the Fantastical Mesmerist Nora Grey, embodying both fragility and immense hidden strength. Forced into deception by her father Tavish, she participates in séances and card readings that blur the line between trickery and true supernatural power.

While Tavish sees her only as a tool for profit, Nairna quietly longs for belonging and stability, remembering the warmth of her grandmother Lottie and the life that was stolen from her. Her encounters with Rona Connell mark the first time she is recognized as an individual with genuine gifts rather than a pawn in someone else’s schemes.

Over the course of the narrative, Nairna evolves from a weary girl complicit in cons to a young woman on the threshold of embracing her destiny as a true medium. Her visions, levitations, and connection to spectral guides place her at the heart of a legacy of women burdened with grief and power, suggesting that her role is not merely to echo the past but to transform it.

Tavish Liath

Tavish is at once pitiable and infuriating, a man consumed by his own failings who drags his daughter down with him. He clings to fabricated claims of noble lineage to mask his insecurities, and his life revolves around petty scams and half-truths.

Though he provides Nairna with food and shelter, his presence in her life is suffocating, denying her the chance to choose her own path. Tavish’s bitterness and dependency contrast sharply with Nairna’s quiet resilience.

Yet he is not portrayed as entirely monstrous—his own troubled origins and the loss of his mother Lottie suggest he is himself a product of trauma and abandonment. Still, Tavish becomes a cautionary figure, embodying what happens when grief and weakness curdle into selfishness rather than strength.

Lottie Liath

Lottie, Nairna’s grandmother, is a figure of both tragedy and defiance. Widowed while pregnant, she fought for justice against the mine owners who dismissed her suffering, only to be crushed by systemic cruelty and personal betrayal.

Her outburst against Mr. Glasscock, and the ensuing imprisonment in Argoll Asylum, illustrate her refusal to remain silent even when silence would have spared her.

The asylum transforms her into both victim and legend, as her visions and psychic manifestations mark her as both extraordinary and dangerous in the eyes of her captors. Lottie’s eventual death in confinement seals her as the archetypal “Wailing Woman,” a spirit whose grief and rage echo across generations.

Her resilience, however, lives on in Nairna, who inherits her gift as well as her burden. Lottie’s story underscores the central theme of women struggling against structures of power that dismiss, exploit, or silence them.

Rona Connell

Rona represents both opportunity and ambiguity in Nairna’s life. Wealthy, elegant, and a believer in spiritualism, she becomes a patron figure who recognizes Nairna’s talents and offers her a chance at genuine growth.

Unlike Tavish, who exploits, or skeptics who dismiss, Rona values Nairna’s gift as something real and worth cultivating. Yet there is also an undertone of calculation in her mentorship—she frames Nairna’s powers within the strictures of the Edinburgh Spiritualists, hinting that she may be guiding as much for her own purposes as for Nairna’s liberation.

Still, for Nairna, Rona represents a doorway into a new life, one that acknowledges her potential beyond trickery and hunger.

Dorothy Kellings

Known as the Scarlet Sunbird, Dorothy is both rival and mirror to Nairna. She has built herself into a spectacle of fame and theatricality, but beneath her grand performance lies the same history of exploitation and reinvention that marks Nairna’s life.

Dorothy is skeptical of Nairna’s authenticity yet also recognizes her as a possible successor or challenger. Their fraught relationship dramatizes the tension between spiritualism as performance and spiritualism as genuine phenomenon.

When Nairna’s uncontrolled levitations overshadow Dorothy’s carefully crafted act, Dorothy’s fury is less about exposure and more about being eclipsed. Dorothy thus embodies the precarious balance of power, fame, and credibility in the world of mediums, offering Nairna both a warning and a challenge.

Dr. Harrison

Dr. Harrison brings an outsider’s perspective to Nairna’s gift, grounding her extraordinary manifestations in the language of science and research.

Unlike Tavish, who exploits her, or Dorothy, who envies her, Harrison treats Nairna as a subject of genuine inquiry. His fascination with her as a rare “physical medium” situates her within a lineage of extraordinary figures, such as Countess Carolina Gustav, suggesting that Nairna may be part of something much larger and more dangerous than she realizes.

Harrison’s role is not purely benevolent, as his intellectual curiosity risks turning Nairna into another specimen of study, but he also validates her abilities in a way others do not, expanding her understanding of her own potential.

Dr. Franz Soekan and Dr. Bothelli

The doctors of Argoll Asylum represent two facets of authority imposed on Lottie. Dr. Bothelli appears at times almost sympathetic, providing food, promises, and moments of apparent gentleness, yet he remains complicit in the structure that confines her.

Dr. Soekan, by contrast, is unambiguously cruel, inflicting pain to force psychic responses and reducing Lottie’s suffering to fuel for his theories. Together they illustrate the way medical and scientific authority in the 19th century often silenced women by branding their grief and anger as madness.

Their exploitation of Lottie provides the darkest counterpoint to Rona’s guidance of Nairna, showing how easily gifts can be weaponized under the guise of study.

Nora Grey

As the book’s namesake, Nora embodies the culmination of generations of grief, resilience, and psychic inheritance. Though her early séances often mingled fraud with flashes of authenticity, she emerges as a medium of startling power, capable of bridging time itself.

Her vision that allows her to aid Lottie in childbirth across decades solidifies her as the connective thread between past suffering and future possibility. Unlike Tavish, who succumbs to bitterness, or Dorothy, who clings to performance, Nora asserts her agency by ultimately stepping away from spectacle and reclaiming her life.

Her story is not just about spiritualism but about self-determination—choosing when to be seen, when to disappear, and how to define her own legacy. In this, Nora becomes the most complete embodiment of the struggle faced by all the women in the novel: to seize control of their stories in a world eager to exploit them.

Themes

Exploitation and Survival

The narrative of The Entirely True Story of the Fantastical Mesmerist Nora Grey consistently shows how exploitation and survival intersect in the lives of its female characters. Tavish Liath manipulates both his own daughter and grieving families, turning their pain into a means for profit.

Nairna is forced to participate in fraudulent séances, her genuine gift exploited for Tavish’s benefit, leaving her yearning for autonomy. The same thread runs through Lottie’s story, though in a different form—her struggle against the mining company illustrates how women in dire situations were often left to fend for themselves with little institutional support.

Her confrontation with Glasscock demonstrates the desperation of a widow fighting for survival, only to be branded as unstable and silenced by patriarchal structures. Later, her incarceration in Argoll Asylum epitomizes the ways society dismissed female resistance as hysteria.

Both Nairna and Lottie survive by navigating spaces where their power is undermined, yet their determination to endure highlights the resilience required of women who were forced to carve out survival from systems designed to consume them. Survival here is never passive; it is a constant negotiation, whether through Nairna’s reluctant participation in her father’s schemes or Lottie’s refusal to submit quietly to her oppressors.

Inheritance of Trauma and Legacy

A powerful theme in the book is the transmission of trauma across generations and the ways legacy shapes identity. Lottie’s tragic confinement and the injustices she endured resonate decades later in Nairna’s life, as if her suffering imprinted itself on her descendants.

The visions and supernatural echoes that Nairna experiences suggest that memory and trauma are not confined to individuals but become part of familial inheritance. The appearance of the “Wailing Woman” at Argoll Downs embodies Lottie’s grief, rage, and unresolved struggle, transformed into a legend that continues to haunt the living.

Nora Grey’s visions further confirm how legacies persist through psychic channels, binding her to the women before her. What emerges is a meditation on how daughters inherit not only resilience and strength but also the unresolved wounds of their mothers.

Legacy is therefore double-edged: it provides grounding in identity and a sense of destiny, but it also carries the weight of unhealed pain that must be confronted and acknowledged.

Gender, Power, and Control

The book portrays power as something unequally distributed, with women consistently positioned under the control of men who exploit or regulate their abilities. Tavish exerts authority over Nairna, forcing her into fraudulent performances for survival.

Dr. Soekan and Dr. Bothelli transform Lottie’s grief into a laboratory experiment, stripping her agency under the guise of science. Similarly, Nora is handled by men like Karl Mendis, who treat her powers as a commodity to be studied, displayed, or marketed.

In each case, female power is simultaneously feared and desired, sought after yet suppressed. Rona Connell provides a counterpoint to this pattern, offering guidance without exploitation, showing that power can exist as mentorship rather than domination.

Yet even in spaces like the Edinburgh Spiritualist circle, male voices of science and skepticism loom large, eager to define the boundaries of what is real. Gender in this story is therefore not simply a matter of personal identity but a battleground where autonomy and control are constantly contested.

The women’s struggle to assert themselves against these forces underscores how deeply patriarchal structures shaped not just their daily lives but also their supernatural destinies.

Spiritualism and the Question of Authenticity

Spiritualism in the book operates as both a source of genuine connection and a realm rife with trickery. Tavish and Nairna’s staged séances reflect the manipulative side of the practice, where illusion caters to grief and desperation.

Yet Nairna’s authentic visions and levitations reveal that real phenomena exist beneath the surface. Dorothy Kellings embodies the tension between spectacle and authenticity, carefully curating her persona while privately acknowledging the fragility of her craft.

For Nairna and later Nora, authenticity becomes a burden; their genuine abilities bring awe but also suspicion, and in being extraordinary they attract both reverence and exploitation. The novel constantly asks whether truth matters in a world where illusion often satisfies more than reality.

For grieving families, even staged connections with lost loved ones provide solace. For researchers, evidence of real phenomena risks dismantling their worldview.

Spiritualism thus becomes a mirror, reflecting both human longing for connection and society’s uneasy relationship with the inexplicable.

Grief and the Supernatural

Grief functions as both catalyst and haunting presence throughout the book. The Lennox family’s yearning to see their daughter again fuels Tavish and Nairna’s first performance.

Lottie’s grief over Elis’s death drives her into confrontation with the mining company, ultimately leading to her incarceration. Nora’s own rise is continually shadowed by visions rooted in past losses, whether they are ancestral echoes or personal burdens.

The supernatural in the story does not simply serve as spectacle—it emerges from the raw pain of loss. Ghosts, visions, and wailing figures are not mere phantoms but embodiments of unresolved sorrow.

The connection between grief and the otherworldly suggests that mourning opens a space where boundaries blur, where the living and the dead share the same stage. In this sense, the supernatural is less about mystery than about memory, a continuation of the emotional lives of those who can no longer speak.

Grief, then, becomes both a destructive force and a channel for transcendence, binding together generations across time.