The Satisfaction Café Summary, Characters and Themes

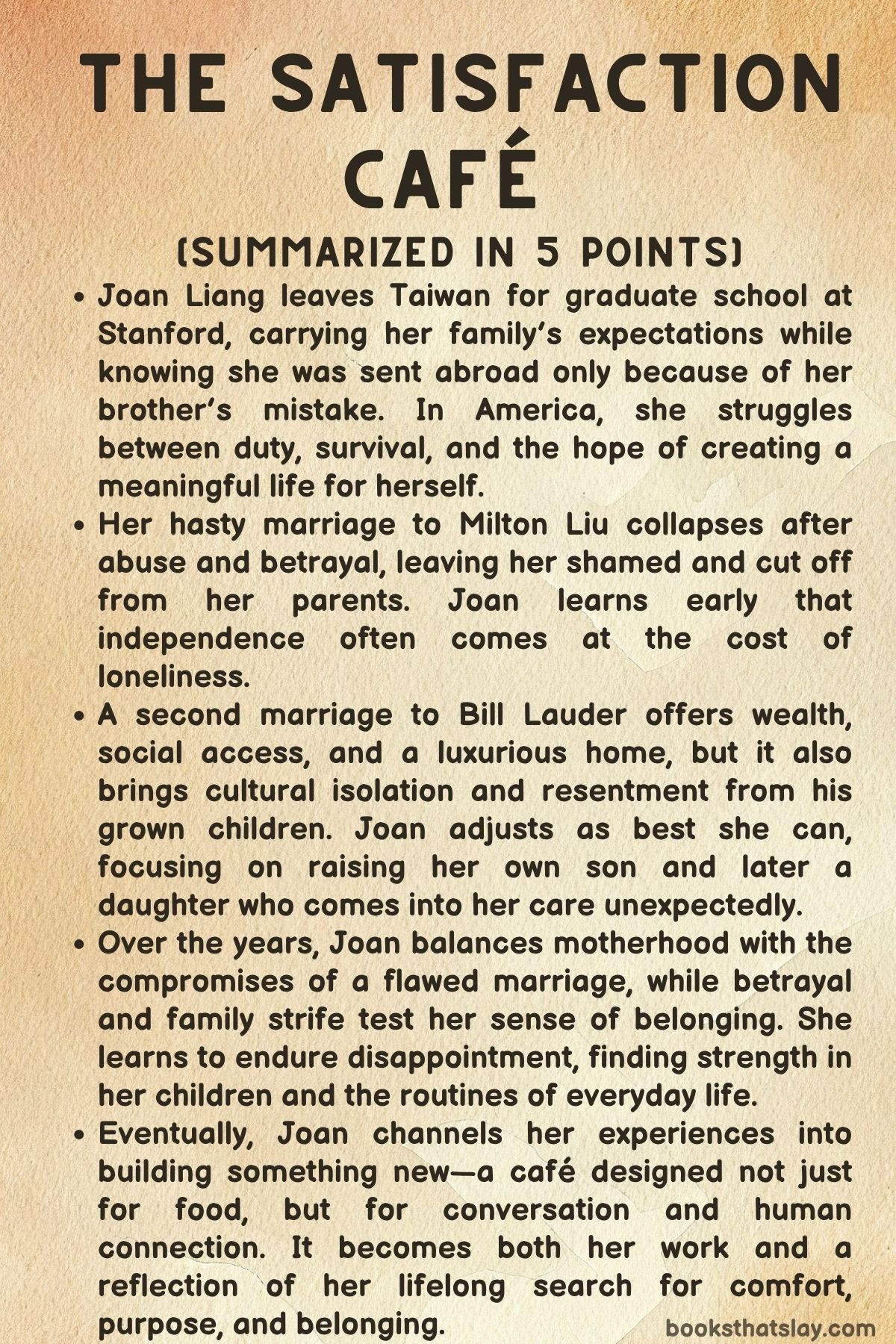

The Satisfaction Café by Kathy Wang is a sweeping multigenerational novel that follows the journey of Joan Liang, a Taiwanese immigrant in America, as she navigates love, family, betrayal, and reinvention. From her modest beginnings as a graduate student in Palo Alto in the late 1970s, Joan’s life becomes a tapestry of resilience against cultural expectations, abusive relationships, and the pursuit of stability.

Across decades, she moves from survival in a lonely attic to wealth and isolation, then into motherhood, loss, and finally the creation of a café that reflects her longing for genuine human connection. The book explores how ambition, compromise, and endurance shape identity, and how meaning can be found even in impermanence.

Summary

Joan Liang arrives in Palo Alto in 1977 to study at Stanford. Pressured by her family in Taiwan, who value her brothers more than her, Joan lives modestly in an attic while working for her landlord.

Her opportunity to study abroad only came because her brother’s academic career was disrupted after impregnating his girlfriend. Joan remains dutiful, cautious, and eager to please, trying to balance the weight of her family’s expectations with her own quiet hopes.

She meets Milton Liu, a confident Chinese architecture student, and marries him quickly in a small courthouse ceremony. At first, Joan is thrilled to imagine a stable life, but Milton soon reveals darker tendencies.

He pressures her into watching pornography and later suggests including his friend Kenny in their intimacy. Horrified and humiliated, Joan refuses.

When Milton becomes violent, she defends herself with steel calipers, injuring him and ending the marriage after only six weeks. Her parents in Taiwan disown her for the divorce, and Milton spreads his version of events, isolating her from her community.

Joan retreats into work, hobbies, and solitude, but loneliness becomes her constant companion.

Her life shifts when she meets Bill Lauder, a wealthy older white man from an influential Palo Alto family. Bill, charming and generous, sweeps Joan into his world of luxury.

They marry, despite opposition from his grown children Juliet and Theo, who view Joan as opportunistic. Joan tries to adjust, learning to navigate social gatherings, charity events, and California high society.

She often feels like an outsider but reminds herself of the stability and beauty her marriage provides. When she becomes pregnant, she embraces motherhood despite Bill’s initial coldness.

Their son Jamie is born, and Joan’s life becomes centered around caring for him, with help from Patty, a trusted nanny introduced through friends.

Bill’s family remains complicated. His sister Misty, reckless and self-absorbed, eventually abandons her baby daughter Leonie.

Joan adopts the child, renaming her Lee, and raises her as her own, though haunted by the sense that she is merely a substitute mother. Joan navigates the challenges of parenting two children while enduring exclusion and judgment from Bill’s social circle.

She is often mistaken for a nanny when out with her children, a reminder of her outsider status.

As the years pass, cracks appear in Joan’s marriage. She discovers Bill’s repeated infidelities, including an affair with a young bookstore manager.

Though furious, she remains with him, weighed down by her children and fear of a second divorce. She accepts her husband’s flaws, convincing herself that no one is perfect.

Still, she struggles with feelings of betrayal, entrapment, and dependence. Family life continues, a mix of stability and pain.

Bill eventually dies, leaving Joan to manage her grief while protecting her children. His son Theo, embittered and unstable, sets fire to Falling House, the family estate.

Joan, Jamie, and Lee escape, but the destruction devastates her, as the house had embodied security and memory. They move to a modest townhouse, where Joan adjusts to a more humble life.

Memories of her childhood in Taiwan resurface—her father’s infidelity, her mother’s cruelty, and an assault by a family acquaintance. These memories shape how she views survival and fate.

Lee grows into adolescence, grappling with her own insecurities and complicated relationships. She becomes involved with an older teacher, and when Joan finds out, she reacts with a mix of cool disappointment and quiet rage.

Lee struggles with her place in the family and the shadows of her mother’s past but remains close to Joan in her own way. Meanwhile, Jamie matures into adulthood, joins the military, and later works in the corporate world, but he struggles with alienation and the gap between his past and present.

Joan, restless and searching for purpose, rebuilds her life by opening the Satisfaction Café on the site of an old video store. Unlike a traditional restaurant, the café offers conversation and companionship.

With Patty’s support, Joan hires hosts to talk with customers, creating a space filled with connection and warmth. To her surprise, the café thrives, and she discovers joy in fostering human interaction.

The work becomes her life’s project, giving her meaning beyond family and wealth.

As time passes, Joan’s health declines. She develops a degenerative brain condition, leading to memory lapses and growing dependence.

Despite her children’s concern, she insists on independence. Eventually, faced with her fading autonomy, she chooses to end her life on her own terms, taking pills during a solitary hike.

She leaves behind small gifts, notes, and reminders for her children, urging them to be kind to one another. Her funeral gathers old acquaintances and family, where grief mingles with reflection.

After her death, both Jamie and Lee struggle with their own futures. Jamie finds purpose in continuing the café, while Lee reflects on her pattern of drifting through relationships and work.

The novel closes with Lee on a plane, wrapped in her mother’s shawl, thinking of Joan’s enduring presence and lessons. She recalls her mother’s reminder that life is fleeting, and that happiness must be pursued despite loss, betrayal, and the inevitability of change.

The Satisfaction Café ultimately traces Joan Liang’s transformation from a young immigrant desperate to please others into a woman who creates a lasting legacy of connection. Her story captures the complexity of survival, the weight of family and identity, and the search for meaning in a world where everything—even love and security—fades with time.

Characters

Joan Liang

Joan is the central figure of The Satisfaction Cafe, a woman whose journey embodies resilience, sacrifice, and the relentless search for belonging. From the beginning, Joan is depicted as dutiful and eager to please, molded by her Taiwanese upbringing where her worth was diminished in comparison to her brothers.

Her move to America represents both exile and opportunity, but her cautious optimism is repeatedly tested by betrayal, abuse, and isolation. Her short-lived marriage to Milton leaves her scarred emotionally and physically, while her second marriage to Bill Lauder thrusts her into a world of wealth that offers stability but also deep loneliness and compromise.

As a mother, Joan demonstrates fierce devotion to Jamie and Lee, creating a nurturing environment even as she grapples with exclusion and suspicion from Bill’s family. Her resilience shines through when she establishes the Satisfaction Café, a venture that finally reflects her values of connection and authenticity.

Even in decline due to her illness, Joan retains her dignity and chooses her end with agency. Her life is defined by survival, adaptation, and a constant negotiation between vulnerability and strength.

Milton Liu

Milton begins as a seemingly charming and talented student, but quickly reveals himself to be manipulative and abusive. His fascination with pornography and eventual attempt to coerce Joan into degrading situations mark him as both exploitative and selfish.

Milton’s violence—slapping Joan when she resists—becomes the catalyst for their marriage’s collapse, leaving her traumatized and ostracized in the Chinese student community. He embodies a form of toxic masculinity that thrives on dominance and disregard for his partner’s dignity.

Though his presence is relatively brief in the narrative, Milton’s betrayal and cruelty cast a long shadow over Joan’s early adulthood, influencing how she navigates intimacy and trust thereafter.

Bill Lauder

Bill represents both opportunity and disillusionment for Joan. As a wealthy, older man from a powerful Palo Alto family, he provides her with stability, sophistication, and the material security she craved after her struggles.

At first, Bill’s warmth and generosity sweep her into a privileged world, but beneath the charm lies a habitual infidelity and a detachment that steadily corrodes their marriage. His relationship with Joan is marked by imbalance: she seeks belonging while he indulges in casual betrayals, assuming her dependence will keep her bound.

Despite his flaws, Bill shows tenderness as a father, particularly to Jamie, and his presence remains significant in Joan’s life even after his death. Bill’s house—Falling House—becomes a symbol of both their union and the fragility of constructed security.

Jamie Lauder

Jamie, Joan’s biological son, grows up under the shadow of his father’s wealth and his mother’s devotion. His path reflects the complexities of belonging and identity, much like his mother’s.

His service in Iraq leaves him physically and emotionally scarred, and his struggle to reintegrate into civilian life reveals a deep sense of alienation. The monotony of corporate work frustrates him, and he finds solace only in tangible, purposeful efforts, particularly when helping with the café after Joan’s diagnosis.

Jamie’s bond with his mother is strong, though marked by unspoken trauma and grief. His eventual closeness with Ellison highlights his gradual acceptance of difference and connection, showing growth beyond his earlier sense of isolation.

Lee (Leonie) Lauder

Adopted after being abandoned by Misty, Lee becomes Joan’s daughter in all but name. Her childhood is marked by confusion about her origins and the sense of being a substitute for someone else’s discarded responsibility.

Despite Joan’s love, Lee grapples with insecurities about her identity, complicated further by societal judgments about her appearance and heritage. As she grows, she struggles with relationships, often choosing older men or paths that seem to mirror her mother’s compromises.

Her encounter with Theo after Bill’s funeral exposes her to danger and betrayal, cementing her awareness of family dysfunction. Yet, by the novel’s end, Lee emerges as a reflective figure, carrying her mother’s legacy of resilience while questioning her own capacity for commitment and meaning.

Her final memory of Joan—wrapped in her shawl on a plane—underscores both loss and continuity.

Misty Lauder

Misty, Bill’s youngest sister, embodies recklessness and instability. Her unpredictability—from flaunting plastic surgery to abandoning her infant daughter—reveals a woman consumed by her own dissatisfaction and inability to nurture.

Despite her flaws, Misty serves as a foil to Joan: where Joan sacrifices and commits, Misty shirks responsibility and drifts. Yet her sporadic returns, whether to gossip, demand money, or offer unsolicited advice, leave lasting impressions on both Joan and Lee.

In many ways, Misty represents the corrosive effects of privilege without discipline, in contrast to Joan’s constant labor to create security and meaning.

Theo Lauder

Bill’s son Theo symbolizes resentment, entitlement, and the destructive potential of unresolved grief. Resentful of his father’s repeated marriages and suspicious of Joan’s presence, Theo spirals into bitterness after Bill’s death.

His disturbing encounter with Lee—complete with alcohol, a gun, and an arson attempt—marks him as dangerous and deeply unmoored. Even after escaping justice for burning down Falling House, Theo drifts aimlessly, reinventing himself in shallow ways but never finding true stability.

He is the embodiment of squandered privilege, consumed by envy and self-pity, and his trajectory contrasts starkly with Joan’s perseverance despite adversity.

Nelson Das

Bill’s lawyer, Nelson, plays a steady, understated role in Joan’s life. Initially tied to her through the prenuptial agreement, he becomes a figure of pragmatism and support, often guiding her through complex legal and financial challenges.

After Bill’s death, Nelson’s presence reassures Joan and her children, and his continued loyalty reflects a kind of surrogate family role. His role, though secondary, emphasizes the importance of reliability and consistency amid chaos.

Ellison

Ellison is a later addition to the narrative but serves as a vital bridge between Joan’s legacy and her children’s future. Gender-fluid and deeply introspective, Ellison represents themes of identity, belonging, and acceptance.

At Atom, they struggle with conformity, and at the café, they find a place of authenticity, which Joan nurtures with quiet understanding. Their bond with Jamie evolves into a tentative friendship built on shared grief and vulnerability.

Ellison’s presence underscores the novel’s commitment to exploring human connection in its diverse forms, highlighting Joan’s ability to embrace difference with empathy and openness.

Themes

Gender Expectations and Power

The trajectory of Joan’s life in The Satisfaction Cafe demonstrates the suffocating weight of gender expectations placed upon her from her childhood in Taiwan through her marriages in America. Her family’s decision to send her abroad only because her brother’s prospects had dimmed reveals how women were considered expendable in comparison to men.

This perception shapes Joan’s internal struggles, as she constantly measures her worth through the roles of dutiful daughter, submissive wife, and devoted mother. In her first marriage with Milton, she endures humiliation and violence rooted in his entitlement to her body and compliance.

When she resists, she is punished physically and socially, isolated from her community. Later, her second marriage to Bill forces her into a new mold—an ornament of respectability for a wealthy man.

Here, her gendered role is redefined not as one of invisibility but as one of performance, where her acceptance in elite social circles depends on her ability to embody grace, loyalty, and silence in the face of betrayal. Joan’s quiet endurance—through Milton’s coercion, Bill’s infidelity, and the gossip of high society—reflects the recurring theme of how women are pressured to maintain dignity even when robbed of agency.

Yet her creation of the café becomes an act of reclamation: she finally crafts a space where conversation and presence, not submission or appearances, define her value. Gender roles still press upon her, but by building the café, she asserts herself beyond them, finding her own meaning.

Marriage and Compromise

Marriage in The Satisfaction Cafe is portrayed not as a union of love and equality but as a negotiation of compromise, security, and survival. Joan’s initial marriage to Milton unravels quickly under the strain of coercion and abuse, revealing how the promises of companionship can mask darker dynamics of control.

Her second marriage to Bill provides material comfort and stability, yet comes with compromises equally profound. Bill’s wealth offers her protection and status, but his serial infidelities and emotional detachment strip the marriage of intimacy.

Joan accepts these betrayals not out of forgiveness but from a pragmatic recognition of her dependence, her fear of being abandoned again, and her responsibility as a mother. This acceptance illustrates how compromise often slides into resignation, as Joan repeatedly tells herself she is fortunate even when she feels trapped.

The marriages of others around her—Misty’s reckless liaisons, Inez’s confessions of emptiness, Bill’s siblings’ fractured relationships—mirror Joan’s experience, creating a wider commentary on the disillusionment inherent in marriage itself. Ultimately, Joan’s endurance within these partnerships reveals a painful truth: that marriage can often require suppressing one’s desires in exchange for stability, but this trade-off leaves scars that resurface in quiet moments of rage and grief.

The café, which she establishes later in life, stands almost as an antidote to marriage—a relationship not bound by contract or compromise but by chosen connection and mutual presence.

Loneliness and Belonging

Loneliness permeates every stage of Joan’s life in The Satisfaction Cafe, shaping her choices and her yearning for belonging. As a foreign student in Palo Alto, she lives in isolation, separated from her family in Taiwan and estranged by cultural distance.

Even in her marriage to Milton, she is alone in her fear and humiliation, silenced by a community that rallies around him instead of her. With Bill, she is again surrounded by people but not embraced by them; the wealth and glitter of parties only amplify her sense of being an outsider, treated with suspicion and disdain by his children and relatives.

Joan’s role as mother temporarily alleviates her solitude, as her bond with Jamie and Lee offers her moments of connection. Yet even here, she is reminded of her otherness—mistaken for a nanny in bookstores or questioned about Lee’s blond hair.

Her loneliness culminates after Bill’s death, when she loses not only a husband but also the house that symbolized her foothold in America. It is only with the founding of the café that Joan begins to transform loneliness into belonging.

The café becomes a sanctuary where companionship is not transactional but genuine, where strangers come to talk and listen. For Joan, this space validates what her marriages, families, and communities had long denied her: the feeling of being seen, not as someone’s wife, mother, or foreigner, but as a person whose presence matters.

Family, Inheritance, and Betrayal

The novel repeatedly interrogates the meaning of family and the betrayals that accompany it. Joan’s family in Taiwan betrays her by disowning her after her divorce, privileging honor over her well-being.

Bill’s family views her as an intruder, more interested in protecting Falling House and their inheritance than accepting her as kin. Theo embodies the destructive consequences of inheritance disputes, as his resentment and sense of exclusion culminate in the arson that destroys Falling House.

Even Misty, through her abandonment of Leonie, betrays the fundamental bond of motherhood, leaving Joan to pick up the pieces. Yet Joan herself is not immune to family betrayals, whether by withholding full truths from her children or choosing silence over confrontation.

At the same time, she creates a redefined sense of family through adoption, friendship with Patty, and the chosen kinship that develops within the café. Betrayal in the book is never simply a single act—it is a pattern woven into the structures of kinship, where property, gender, and loyalty collide.

Family becomes both a source of identity and the site of deepest wounds, and Joan’s navigation of this tension underscores how betrayal can fracture blood ties but also open the door to new forms of connection.

Survival and Reinvention

At its core, The Satisfaction Cafe is a story of survival and the constant reinvention required to endure. Joan survives Milton’s violence, the rejection of her family, the humiliation of social exile, Bill’s betrayals, the destruction of her home, and finally the gradual decline of her health.

Each crisis forces her to rebuild, to imagine a different way forward, even when it means suppressing grief or accepting compromises. Reinvention comes in many forms: as a divorced immigrant reinventing herself as a wealthy man’s wife; as a widow choosing to build a café on the ashes of loss; and as a mother who raises children not bound by blood but by choice.

Joan does not present survival as triumphant but as weary, shaped by scars and loneliness. Yet there is resilience in her refusal to collapse entirely—she continues, she creates, she adapts.

Even her final act of ending her life is a form of control, an insistence on choosing the terms of her survival’s end. The café, in this sense, represents her most profound reinvention: a physical manifestation of her ability to transform loss into creation, grief into connection, and solitude into community.

Her life demonstrates that survival is not merely continuing to exist but continually remaking oneself in the face of relentless change.