Atomic Hearts by Megan Cummins Summary, Characters and Themes

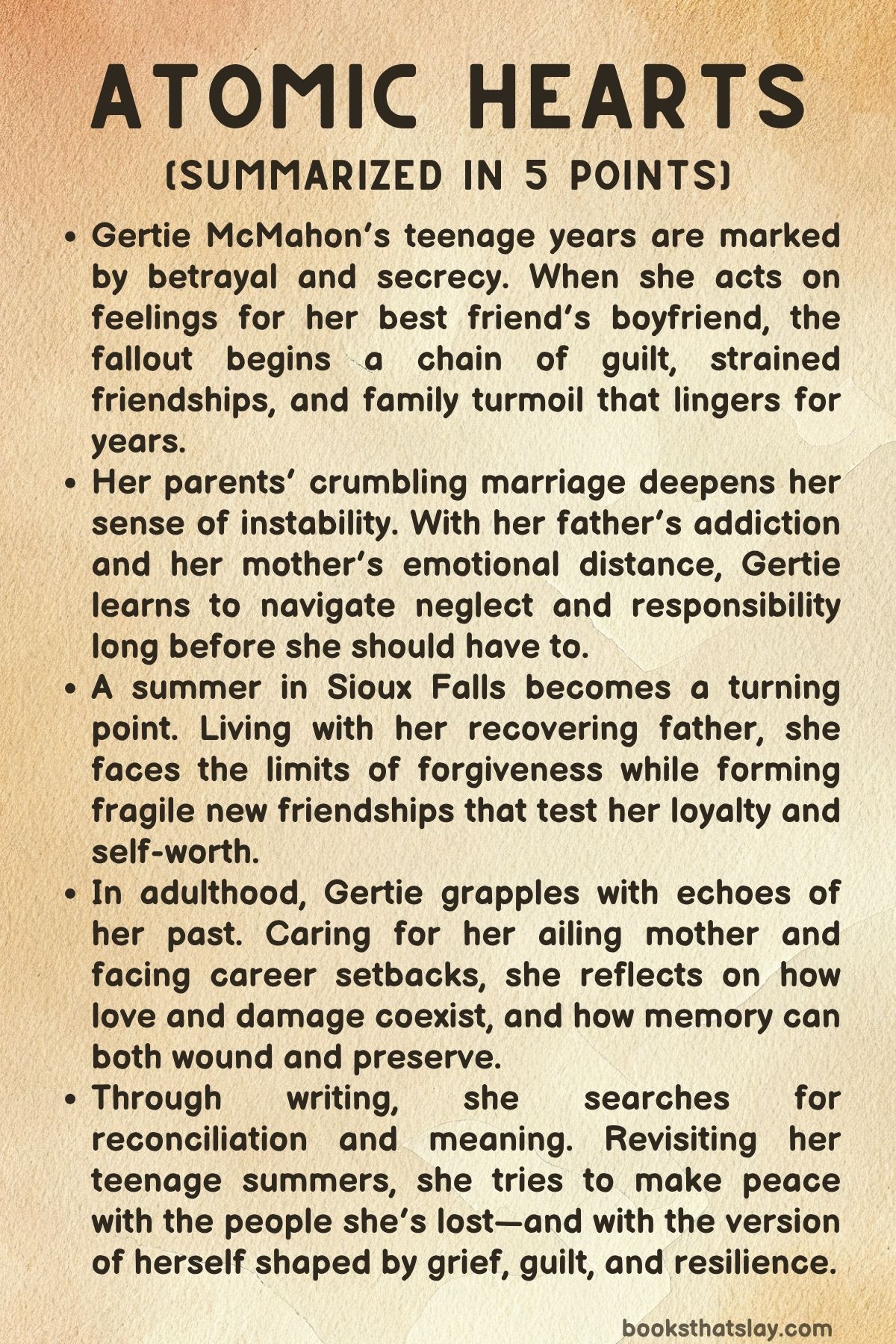

Atomic Hearts by Megan Cummins is a coming-of-age novel that traces the fractured journey of Gertie McMahon, a young woman shaped by trauma, guilt, and the echoes of addiction within her family. Moving between Gertie’s adolescence and adulthood, the story explores how one impulsive act reverberates through years of loss, friendship, and fragile recovery.

Through alternating timelines and moments of haunting introspection, Cummins examines the painful inheritance of family dysfunction and the complicated ways love and forgiveness manifest when survival becomes the only language left. It’s a portrait of growing up amid chaos, learning to carry both damage and hope.

Summary

The story of Atomic Hearts centers on Gertie McMahon, whose adolescence is marked by secrecy, fractured family ties, and a betrayal that reshapes her life. Told across intertwined timelines—her teenage years in the Midwest and her adult life fifteen years later—the narrative reveals how her past continues to influence her present.

As a sixteen-year-old, Gertie is caught in an emotional storm. Her best friend Cindy Fellows is dating Gabe, a charming but manipulative boy Gertie secretly loves.

Both girls are bound by shared pain: their fathers are addicts, and they’ve learned to mask instability with defiance. When Cindy leaves town during winter break, Gertie attends a party to distract herself.

There, she encounters Gabe, who claims to have broken up with Cindy. In a haze of longing and alcohol, Gertie gives in to his advances, and they have sex in an upstairs bedroom.

The encounter leaves her shaken, and when Gabe takes a compromising photo of her, she feels both violated and complicit. Ashamed, she flees into the freezing night, slipping on ice and breaking her wrist.

Her father, still struggling with sobriety, drives her to the hospital, marking one of their last moments together before he is sent to rehab and her parents separate for good.

Months later, guilt and secrecy corrode Gertie’s friendship with Cindy. When Cindy confides that Gabe has insulted her, suggesting Gertie is “easy,” Gertie is devastated but remains silent.

During a summer evening by a backyard fire, an aerosol can explodes, wounding Gertie’s thigh. Fearful of punishment and costs, she refuses help, cleaning the wound herself.

Infection sets in, and she collapses alone at home. Discovered by a realtor showing the house, she’s hospitalized with sepsis.

Her mother, away with her boyfriend Vaughn, rushes back, more angry than concerned. When Cindy visits the hospital, the girls briefly reconnect, sharing laughter and a symbolic gift—a star they “own” together.

But the fragile peace shatters when Gertie’s mother, now engaged to Vaughn, pressures her to move to Europe. In rebellion, Gertie insists she’ll live with her father instead.

The story of that winter and summer closes with her realization that one night’s mistake has splintered her family and left permanent scars.

Years later, as a teenager again, Gertie spends a summer with her father, Mark, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Her mother, planning a trip to Europe with Vaughn, encourages the visit, but Gertie’s true motive is escape—from Cindy, from guilt, and from the memory of Gabe.

Her father’s apartment is filthy, and his addiction evident, yet she clings to the illusion of normalcy. She finds new acquaintances at a grocery store—twins Adam and Austin, their friends Willa, Jill, and Lucas—and begins working there, trying to craft a new version of herself.

Her bond with Adam grows tender, though she remains emotionally guarded. Gabe resurfaces through a late-night call, reviving old turmoil.

Her father’s neglect worsens; prescription bottles pile up, and Gertie senses the cycle repeating. Through writing a novel about two lovers, Jamie and Hayden, she begins to process her pain, using fiction to reimagine control over her own story.

In the adult timeline, Gertie is married to Ciarán, an Irishman she met abroad. They live in Michigan, caring for her ailing mother, Carla, whose multiple sclerosis and stubbornness dominate their lives.

Gertie, recently fired from her remote nonprofit job, struggles with burnout and resentment. Her relationship with Ciarán is loving but strained by the weight of caretaking.

Her mother refuses treatment, speaks flippantly about death, and rails against her own dependence. Through their tense exchanges, buried grief surfaces: Carla once called a suicide hotline when Gertie was a baby, saved only by her sponsor’s intervention.

Gertie feels both anger and empathy, recognizing echoes of her father’s self-destruction in her mother’s defiance.

The past timeline intensifies as Gertie’s life unravels in Sioux Falls. Her secret photo resurfaces at her workplace, circulating among coworkers.

Her manager fires her under the guise of misconduct, and she retaliates by destroying a coworker’s phone before storming out. That night, she finds her father unconscious in his car after overdosing.

Acting on instinct, she breaks the window, injures herself, administers Narcan, and calls for help. At the hospital, a social worker named Sarah comforts her and arranges for Gertie to stay with Cindy’s family in Michigan.

Before leaving, Gertie visits her father’s bedside, unsure if he will survive. She signs her final paycheck over to him and returns home, uncertain whether she’s escaping or abandoning him.

Back in Michigan, Gertie and Cindy reunite under strained circumstances. Their confrontation on the lawn—charged with years of silence and betrayal—ends in forgiveness.

They acknowledge the damage Gabe caused and the loneliness each carried. Inside the house, they link arms, restoring the bond that once anchored them.

In the adult storyline, Gertie reconnects briefly with Adam, now living in New York. He reveals that his twin, Austin, has died of an overdose.

Their conversation quickly turns sour, dredging up mutual blame and regret. Gertie leaves the bar realizing that closure may never come from others, only from accepting her past.

Later, she discovers that her mother has hidden a stash of Xanax “for dignity,” a euphemism for control over her own death. Furious yet helpless, Gertie confronts her, fearing another collapse.

Their relationship wavers between fierce love and exhaustion, both women haunted by choices they cannot undo.

A final revelation reframes the narrative. Gertie confesses that her earlier account of reviving her father was a story she told herself to survive.

In truth, the Narcan didn’t work—he died in the car that morning. Her writing became a means to resurrect him, to rewrite grief into a version she could bear.

As an adult, she still writes, channeling loss into words, preserving fragments of love amid decay. In the closing scene, she holds Cindy’s baby, her bandaged hand resting on the child, symbolizing both injury and renewal.

When asked if she has been writing, she answers quietly, “A little”.The novel ends on this understated note—acknowledging that healing is imperfect, memory unreliable, and survival itself a creative act. Through Gertie’s story, Atomic Hearts traces how the past shapes the present, how guilt becomes inheritance, and how even the most fractured love can still leave behind a light to follow.

Characters

Gertie McMahon

Gertie McMahon stands at the heart of Atomic Hearts, her life and psyche unfolding across dual timelines—her turbulent adolescence and her reflective adulthood. As a sixteen-year-old, she is tender, impulsive, and burdened by secrets far heavier than her age can bear.

Her crush on Gabe, her best friend’s boyfriend, and the shameful night that follows, set off a chain reaction of guilt and loss. This moment defines her adolescence and becomes the origin point for her lifelong struggle with self-worth and control.

Her relationship with her parents, especially her father, is deeply complex. Mark’s addiction forces Gertie into premature maturity; yet, she craves his affection and forgiveness, even when she recognizes his instability.

In adulthood, Gertie’s voice becomes one of reflection and reconstruction. Now a writer, she uses storytelling as a form of self-salvation, rewriting memories that once destroyed her.

The scars of betrayal—by Gabe, Cindy, and even her own choices—remain visible in her hesitancy to trust and her conflicted relationship with her mother, Carla. Yet, Gertie is never static.

She evolves from a girl trapped in cycles of secrecy and caretaking into a woman who finally begins to define her own boundaries and truths. Her survival is both literal and emotional, and her decision to tell her story—truthfully at last—is her final act of reclaiming power.

Mark McMahon

Mark McMahon, Gertie’s father, embodies the tragedy of addiction and the lingering ache of a parent who loves yet continually fails. Once a dreamer with creative aspirations, his life unravels under the weight of dependency, leaving him oscillating between tenderness and neglect.

His relationship with Gertie is steeped in unspoken regret; he sees her both as a daughter and a mirror reflecting his brokenness. Despite his relapses, fleeting moments of care—like attempting to prepare his apartment for her visit—show that love persists beneath his self-destruction.

In Gertie’s memory, Mark becomes almost mythic: a man whose downfall defines her understanding of love, forgiveness, and grief. Even after his death, his presence lingers through letters and through the fictional worlds Gertie creates to resurrect him.

Mark’s life, and eventual loss, form the emotional core of Gertie’s identity—her compassion, her self-blame, and her creative drive all trace back to him. His death, and her reimagining of it, become the clearest expression of the blurred boundary between truth and mercy that defines the novel.

Carla McMahon

Carla McMahon, Gertie’s mother, is a study in emotional survival. Hardened by years of disappointment with her husband’s addiction, she transforms into a woman whose strength borders on cruelty.

Her pragmatic approach to life—pursuing stability, relationships, and eventually remarriage—contrasts sharply with Gertie’s emotional vulnerability. Yet beneath her harshness lies exhaustion, fear, and a lingering maternal love that expresses itself awkwardly.

Her relationship with Gertie is marked by tension: Carla wants control; Gertie craves understanding.

In later years, Carla’s decline through illness reveals her vulnerability and her humanity. The disease strips away her defenses, forcing mother and daughter into painful intimacy.

Their conversations about mortality, regret, and love reveal the cyclical nature of their bond—each resenting yet needing the other. Carla’s acknowledgment of her own suicidal past and her attempts to secure dignity in her illness transform her from a symbol of bitterness into one of tragic resilience.

Through her, the novel explores the blurred lines between survival and surrender, love and control.

Cindy Fellows

Cindy Fellows represents both Gertie’s lost innocence and the fragility of adolescent friendship. The two share a childhood marked by chaos and parental neglect, forming a sisterhood bound by shared pain.

However, Cindy’s possessiveness and insecurity fracture this bond once Gabe enters the picture. Her warning to Gertie about Gabe’s attraction and her later betrayal through gossip expose the cruelty that often hides within intimacy.

Yet, Cindy is no villain—she, too, is a casualty of broken families and misplaced loyalties.

As the story progresses, Cindy’s return to Gertie’s side at the hospital and their exchange of forgiveness mark one of the few truly tender reconciliations in the book. Her gift of the shared star certificate becomes a fragile emblem of enduring affection amid betrayal.

Cindy matures into a symbol of reconciliation—the possibility that not every wound must fester, and that friendship, though imperfect, can outlast shame.

Gabe

Gabe is the catalyst of destruction in Atomic Hearts, a figure of charm, manipulation, and moral emptiness. His relationship with Gertie and Cindy exposes his capacity to control and demean under the guise of affection.

For Gertie, he represents forbidden desire and the perilous confusion of adolescence—how attention from someone magnetic can feel like validation, even when it brings ruin. His cruelty, particularly through the leaked photo and his taunting messages, transforms him from an object of longing into one of fear and disgust.

Gabe’s character serves as an indictment of toxic masculinity and the social structures that protect it. His actions ripple through every aspect of Gertie’s life, haunting her relationships and her sense of self.

Yet, he is also portrayed with chilling realism—a boy molded by a world that never taught accountability. His final text to Gertie—You need to be more careful—crystallizes his role as both predator and mirror to her own self-blame.

Adam

Adam emerges later as a complex counterpart to both Gabe and Gertie. Sensitive, intelligent, and flawed, he embodies the gray space between love and damage.

His early kindness toward Gertie contrasts sharply with his later judgment, reflecting how affection can sour into resentment when burdened by guilt. Their connection, marked by intimacy and misunderstanding, parallels Gertie’s broader struggle with trust.

When he calls her a “slut” in anger, it reopens her oldest wound—the conflation of desire with shame.

Their reunion years later carries the weight of everything unsaid. Adam’s grief for his brother, Austin, and his bitterness toward Gertie expose how time does not erase trauma but transforms it.

In their final encounter, Gertie’s decision to walk away from him signifies growth—the ability to stop living in cycles of penance and move toward self-forgiveness. Adam, ultimately, represents both what Gertie lost and what she had to leave behind to heal.

Vaughn

Vaughn, Carla’s long-term boyfriend and later fiancé, stands as a symbol of superficial stability. To Carla, he offers escape from the chaos of her marriage; to Gertie, he embodies hypocrisy and emotional abandonment.

His dismissiveness and self-absorption deepen the gulf between mother and daughter. Vaughn’s presence is less about his individual personality and more about what he represents—the adult world’s failure to offer true security.

His influence lingers as a shadow over Gertie’s understanding of love and trust, shaping her skepticism toward men and authority.

Ciarán

Ciarán, Gertie’s husband in adulthood, offers a counterbalance to the destructive men of her past. He is patient, empathetic, and emotionally grounded.

Their relationship, forged through shared vulnerability, becomes a testament to healing without forgetting. Ciarán listens, supports, and stands beside Gertie as she confronts her mother’s illness and her own creative fears.

Yet their bond is not idealized—it carries tension born from exhaustion, caretaking, and the ghosts of the past. Through Ciarán, the novel imagines love not as rescue but as coexistence with pain.

He becomes the quiet anchor in Gertie’s long journey toward acceptance.

Ansel

Ansel, Mark’s deceased brother, appears briefly but powerfully as a spectral influence. His failed literary ambitions and early death symbolize both inherited fragility and artistic legacy.

For Gertie, discovering his unpublished novel is a moment of revelation: art can preserve what life cannot. Ansel’s defiance against oblivion through writing mirrors Gertie’s own purpose as an author.

He becomes a silent guide, proving that storytelling—however imperfect—is an act of survival.

Themes

Shame and Secrecy

In Atomic Hearts, shame operates as both a catalyst and a cage for Gertie McMahon, shaping her adolescence and adulthood. Her decision to hide the truth about sleeping with Gabe becomes the first in a series of silences that define her emotional life.

The secrecy festers, not only because of moral guilt but because of how her environment reinforces humiliation as an inescapable inheritance. Raised in the shadow of addiction, instability, and gossip, Gertie learns early that exposure equals vulnerability.

The photo Gabe takes without consent, and its later circulation, literalizes this fear—her body becomes a public object, and she internalizes the violation as self-blame. Shame becomes hereditary too; her mother hides her pain behind anger, and her father hides his despair behind narcotics.

The novel shows how concealment is learned behavior in fractured families, where appearances are more manageable than truths. As Gertie matures, the secrecy hardens into her creative instinct: she writes fiction not to confess but to reimagine, to replace her unbearable memories with controlled narratives.

Her art becomes both rebellion and refuge, a way of converting humiliation into authorship. Yet the act of writing also exposes her—language cannot fully mask what it reveals.

By the time she confronts the truth of her father’s death, shame transforms from something corrosive to something redemptive: by admitting the lie in her narration, she reclaims her agency. The theme thus evolves from secrecy as survival to honesty as liberation, charting Gertie’s painful journey from concealment to self-definition.

Cycles of Addiction and Caregiving

Addiction in Atomic Hearts is depicted not as a singular tragedy but as a generational echo. Gertie’s father’s substance abuse and her mother’s bitterness form a volatile pattern that Gertie unconsciously repeats in her emotional life.

Her adolescence is spent oscillating between caretaking and resentment, caught in the gravitational pull of her parents’ dependencies. She tends to her father during his relapses and to her mother during her illness, performing the emotional labor of an adult before understanding what it costs.

The novel blurs the boundary between love and responsibility—Gertie’s affection is bound to crisis, her self-worth measured by how well she rescues others. Even her relationships with men mirror this pattern: she is drawn to brokenness, to those who demand care but offer none.

Addiction extends beyond substances—it becomes a metaphor for the compulsion to fix, to cling, to atone. Her writing, too, reflects this repetition, as she revisits and reworks her past in endless drafts.

The story suggests that healing requires breaking not only chemical habits but emotional ones: the need to define love through suffering. By the end, Gertie’s decision to tell the truth about her father’s death marks a small but vital rupture in the cycle.

Instead of preserving him through illusion, she allows loss to stand as it is. The novel’s compassion lies in this recognition—that the act of caregiving, when born from guilt, is another form of addiction, and only through acceptance can one begin to recover.

Friendship and Betrayal

The relationship between Gertie and Cindy forms one of the novel’s most poignant tensions, exploring how friendship between girls can hold both tenderness and cruelty. Their bond, rooted in shared trauma and mirrored family dysfunctions, initially offers stability in a chaotic world.

Yet beneath their intimacy runs a quiet competition for control, affection, and validation. The betrayal with Gabe is not only sexual but symbolic—Gertie’s transgression shatters the illusion that either girl could remain untouched by the cycles that defined their parents.

The betrayal deepens when the explicit photo circulates, forcing both to confront the ways their identities have been shaped by male perception. Even as their friendship fractures, they remain tethered by a strange loyalty, one that persists through anger and silence.

When Cindy later returns in adulthood, their reconciliation carries the weight of years of unspoken understanding. Their shared ownership of a star, a small token from their youth, becomes a fragile metaphor for permanence amid impermanence.

Through them, the novel portrays female friendship not as a sanctuary from harm but as a mirror reflecting its consequences. It examines how love between friends can survive betrayal—not by erasing the past but by acknowledging it.

Gertie’s eventual confession, both to herself and through her writing, transforms the betrayal into testimony. The friendship becomes the novel’s quiet backbone, showing that forgiveness, though incomplete, is possible even when innocence cannot be restored.

The Inheritance of Trauma

Across generations, Atomic Hearts traces how unhealed wounds replicate themselves in new forms. Gertie’s parents’ marriage, strained by addiction and resentment, sets the blueprint for her own relationships and self-concept.

Her father’s self-destruction and her mother’s bitterness leave her caught between pity and rebellion. The trauma is not confined to memory; it becomes behavioral, shaping how she interprets love, risk, and forgiveness.

Each time Gertie reaches for connection, she also braces for loss. Even her adult life reflects this inheritance—her partnership with Ciarán is stable yet shadowed by the constant expectation of collapse.

The intergenerational trauma extends beyond the family to the social landscape: a world where emotional neglect and moral double standards leave young women to navigate pain without language. The novel does not sensationalize trauma but portrays its quiet persistence, how it embeds in daily gestures and choices.

The shift between timelines underscores that time alone cannot dissolve inherited pain—it merely changes its expression. Through her writing, Gertie attempts to interrupt the transmission, transforming her family’s story from repetition into reflection.

In acknowledging her father’s death truthfully, she resists the comforting fiction of survival and embraces the harder work of remembrance. The theme asserts that healing from trauma requires more than endurance; it demands the courage to confront history and reshape its narrative.

Forgiveness and Self-Redemption

Forgiveness in Atomic Hearts is portrayed not as absolution but as an act of endurance. Gertie’s life is defined by a longing to be forgiven—by Cindy, by her parents, by herself—but every attempt at reconciliation is complicated by the impossibility of erasing harm.

Her writing becomes the space where she rehearses forgiveness, rewriting moments of failure into gentler fictions. Yet redemption in the novel does not arrive through apology or closure; it arrives through the acceptance of ambiguity.

Gertie cannot save her father, undo her betrayal, or repair every relationship she damaged, but she can refuse to lie to herself any longer. The adult Gertie, caring for her mother and confronting her own exhaustion, learns that forgiveness is not an event but a practice of survival—an ongoing negotiation between compassion and accountability.

By revealing that her earlier narration was a softened truth, she performs the novel’s central moral act: she replaces the comfort of invention with the integrity of confession. This gesture transforms her from a passive witness of pain into its author and interpreter.

Forgiveness here is not a gift granted by others but a reclamation of agency—the ability to live with what cannot be undone. In closing the story with a quiet acknowledgment of both loss and endurance, the novel suggests that redemption is not found in forgetting, but in the decision to remember truthfully and continue forward.