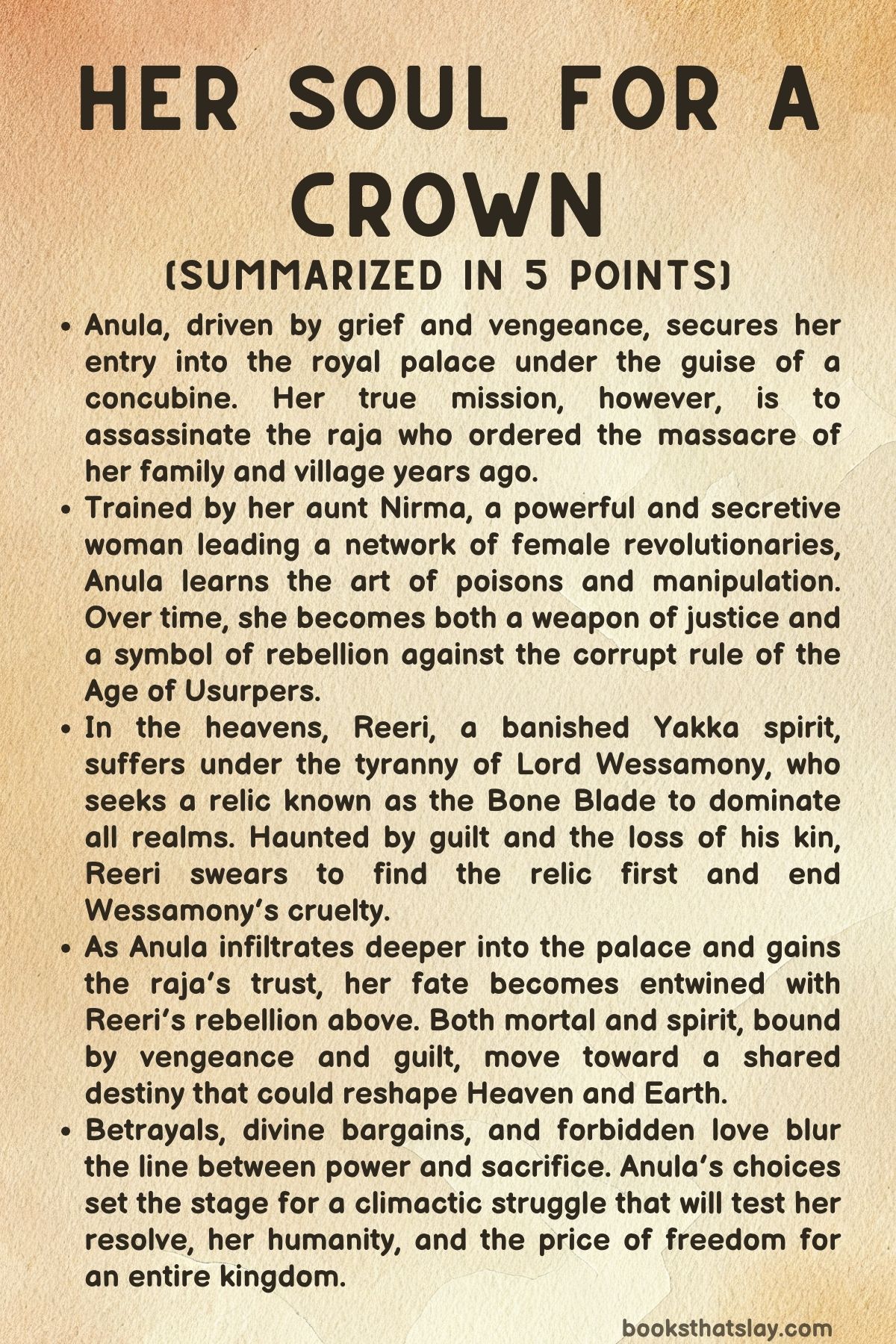

Her Soul for a Crown Summary, Characters and Themes

Her Soul for a Crown by Alysha Rameera is a dark fantasy epic set across two realms—the mortal kingdom of Anuradhapura and the celestial dominion of the Yakkas. It follows Anula, a young woman scarred by tragedy, who infiltrates the royal palace to assassinate the tyrant raja responsible for her family’s death.

Her quest for vengeance intertwines with the fate of Reeri, a fallen spirit seeking redemption against his cruel master in the heavens. Bound by ancient bargains and blood oaths, both mortal and divine worlds collide in a story of power, justice, and rebirth, where love and wrath reshape the course of destiny.

Summary

Anula’s journey begins in the shadowed streets of the inner city, where desperation drives her to strike a deal with Nuwan, a palace guard. When he tries to assault her, she defends herself using a paralyzing poison, nearly killing him.

This violent encounter sets the tone for her ruthless resolve—to enter the palace as a concubine and bring down Raja Mahakuli Mahatissa, the man who destroyed her family and village. Guided by her aunt Nirma, a powerful widow and leader of a secret resistance of women, Anula’s mission is not only assassination but transformation—ending the corrupt “Age of Usurpers” and restoring justice to the realm.

Inside the palace, Anula witnesses devotion to the Yakkas, spirits once revered but now feared. Though she has long lost faith in the gods, she carries her own kind of faith: in vengeance and control.

Her training with Nirma has made her an expert in poisons, politics, and deception. The palace rituals, meant to purify the concubines, only fuel her defiance.

Her past returns in flashes—the night her village burned, her father executed with molten silver, her mother’s final cry—and with it the memory of unanswered prayers. She once begged both Heaven and the Blood Yakka of the Second Heavens for help.

None came.

Far above, the Blood Yakka Reeri lives in exile. Once a being of purpose, he now drifts among cursed spirits under Lord Wessamony’s rule.

Wessamony’s hunger for divine supremacy drives him to search for the Bone Blade, an ancient relic that could destroy the balance between Heaven and Earth. When Reeri defies him, Wessamony murders one of their kin as punishment.

Consumed by guilt, Reeri vows to find the relic first—not for his master, but to destroy him.

Meanwhile, Anula’s infiltration of the palace deepens. Her encounter with a poor maid named Premala hints at the suffering of the people and reminds her why her mission matters.

The web of betrayal thickens when she learns her aunt’s plan is broader than assassination—it’s rebellion. Nirma’s group of women has been secretly shaping politics and spreading knowledge to reclaim power from men who rule through fear and divine manipulation.

As Anula charms the raja, she uses a potion to cloud his judgment, making him believe she is his destined queen. Her deception works—he declares her his chosen wife.

But before she can complete her revenge, chaos strikes. The usurper Chora Naga invades the palace.

Amid the bloodshed, Nirma is betrayed and killed, urging Anula to remember the Yakkas with her dying breath. In grief and fury, Anula flees to the palace shrine, where she makes a forbidden offering—her soul—to the Blood Yakka Reeri.

Her prayer is for the crown, not love or mercy, but power to rule and avenge. Reeri answers, binding his essence to hers in a pact that will alter both their worlds.

Through this bond, Reeri and his brethren return to Earth, tethered through Anula’s soul. But the connection awakens old memories in him—of the night she once called to him as a terrified child.

Haunted by guilt, Reeri becomes protective of her, while she burns with vengeance. When Anula confronts Prophet Ayaan, one of her family’s murderers, he confesses that the massacre of her village was ordered by the raja under Wessamony’s influence.

The slaughter was meant to locate the very relic the gods themselves seek—the Bone Blade. Enraged by this revelation, Anula kills him with poison, realizing that divine corruption reaches far beyond mortal kings.

As Reeri and his brothers attempt to find the relic, they discover their world’s balance decaying. Reeri learns that only a human linked to both Heaven and Earth can wield the Bone Blade’s true power.

That human is Anula. Their alliance strengthens as they pursue the relic, even as new threats arise from the Kattadiya—a secret order of ritualists who claim to banish demons but are revealed to have once summoned Wessamony himself.

When Anula uncovers their violent rites and blood oaths, she understands she has become both weapon and target. Her pact with the Yakkas binds her fate to theirs; she cannot speak their secrets or walk away alive.

Despite growing affection between her and Reeri, the war between Heaven and Earth accelerates. The relic they recover proves false, forged by deceit.

Anula vows to find the real Bone Blade and end Wessamony’s reign. Guided by Reeri, she learns to wield her inner strength, not just poison and deceit, but the voice of justice that echoes through realms.

Her vengeance evolves into leadership. When she faces Commander Dilshan—the last of those responsible for her family’s murder—she chooses justice over rage, signaling her transformation from assassin to queen in spirit.

The final confrontation brings the two worlds crashing together. The Great Sword, Wessamony’s weapon, vanishes into a dark seam that devours the heavens.

In the chaos, Anula wields the true Bone Blade. With Fate itself beside her, she uses its power to restore what was destroyed—lives, land, and the balance between gods and mortals.

The act of salvation costs her dearly; she must cut through Death’s many hands, freeing every trapped soul. Among those she saves is Bithul, her loyal guard, and Premala, who becomes a leader in her own right.

But Reeri and the Yakkas are pulled back into the cosmos, their fates uncertain.

When the heavens stabilize, Anula finds herself alone but victorious. With Wessamony gone, a foreign prince seizes Anuradhapura.

Anula leads an uprising through portals hidden in “blessed paintings,” reclaiming her city. In a final act of defiance, she kills the usurper with poison and declares that no man will ever rule her land again.

Her people, witnesses to her courage, proclaim her the first raejina—sovereign queen of a liberated kingdom.

In the heavens, Reeri is reborn, freed from his master’s curse and crowned Lord of the Second Heavens. His reign promises peace instead of conquest.

He returns to Anula, and together they share a bond that transcends realms. Their reunion marks the dawn of a new age—for Heaven and Earth alike—where power no longer belongs to the divine or the damned, but to those who fight for balance.

In her final act as queen, Anula destroys the Bone Blade, ending the age of relics and restoring free will to all beings.

Her Soul for a Crown concludes with harmony reclaimed: Anula ruling Anuradhapura with wisdom and fire, Reeri reigning above with mercy, their love bridging mortal and celestial worlds. The Age of Usurpers ends, giving rise to an age of renewal—where vengeance becomes justice, and sacrifice gives birth to freedom.

Characters

Anula

Anula stands as the central figure of Her Soul for a Crown, embodying the complex interplay of vengeance, destiny, and redemption. Born into tragedy, she transforms from an innocent girl into a cunning and fearless woman molded by loss and betrayal.

Her family’s brutal death in Eppawala ignites a lifelong mission of justice that consumes her entire being. Throughout the narrative, Anula’s evolution from a grieving survivor to the first raejina of Anuradhapura underscores her resilience and defiance against patriarchal and divine powers alike.

Her intelligence, mastery of poisons, and ability to navigate both courtly and spiritual politics mark her as a strategist driven not by blind rage but by a larger vision of liberation. Yet beneath her calculated resolve lies a deep moral conflict—her hatred for the gods contrasts sharply with her longing for meaning and faith.

Her eventual bond with the Yakka Reeri bridges the mortal and celestial worlds, reflecting her journey from vengeance to balance. By the story’s end, Anula redefines power—not as domination or retribution, but as the courage to rebuild a world shaped by compassion and equality.

Reeri

Reeri, the Blood Yakka, mirrors Anula in many ways, serving as her spiritual counterpart in the celestial realm. Once a being of light, he becomes a fallen god burdened by guilt, condemned to wander among mortals’ prayers and curses.

His arc is one of redemption—a quest to reclaim purpose and restore the moral equilibrium lost to his master, Wessamony. When Reeri and Anula’s paths intertwine, his stoic detachment gives way to empathy, love, and remorse.

His connection to Anula transcends the mortal-divine divide, symbolizing the union of rage and mercy, death and life. Through her, Reeri rediscovers the essence of creation and the responsibility that comes with power.

His eventual ascension to Lord of the Second Heavens marks not victory, but reconciliation—between Yakkas and Divinities, between vengeance and forgiveness. His journey represents the transformation of divine cruelty into divine compassion, restoring the fractured cosmos through love and humility.

Nirma

Nirma, Anula’s aunt and mentor, embodies the shadowed matriarchal power that operates behind kingdoms. Charismatic yet ruthless, she is both savior and manipulator.

Her revelation as an assassin serving “justice” blurs the moral boundaries between righteousness and fanaticism. Nirma channels her grief and disillusionment into rebellion, forming a secret network of women scholars and killers who fight corruption with intellect and venom.

For Anula, Nirma is both guide and cautionary figure—the woman who teaches her strength but also the peril of letting vengeance eclipse humanity. Her death, pierced by betrayal, seals her role as the tragic visionary whose dream of liberation lives on through Anula.

Nirma’s legacy endures not through bloodshed, but through the empowerment of women who dare to rewrite their fates in a world ruled by men and gods.

Premala

Premala serves as a mirror to Anula’s conscience, representing innocence and moral grounding amidst pervasive deceit. Initially a humble maid, her empathy and quiet courage gradually reveal a core of resilience.

Through her friendship with Anula, Premala evolves from a frightened servant into a spiritual leader, ultimately becoming the new guruthuma after Hashini’s death. Her transformation underscores the novel’s recurring theme of empowerment through compassion.

Unlike Anula or Nirma, Premala’s strength is not rooted in vengeance but in the preservation of faith and humanity. Her defiance of cruelty and her willingness to forgive signal the healing of a world fractured by wrath.

By the novel’s conclusion, Premala embodies the balance between mortal devotion and divine wisdom, symbolizing the rebirth of moral order in Anuradhapura.

Wessamony

Wessamony, Lord of the Second Heavens, represents the corrupting influence of absolute power. Once a divine being of order, his descent into tyranny parallels that of mortal despots like Raja Mahakuli Mahatissa.

His insatiable hunger for the Bone Blade reflects a cosmic hubris—the desire to surpass even the Divinities who created him. Wessamony’s cruelty toward the Yakkas, his twisted view of creation, and his manipulation of mortals expose the rot within divine hierarchies.

He is not merely a villain but a commentary on the cyclical nature of oppression: gods and men alike fall when they seek dominion instead of harmony. His downfall at the hands of Anula and Reeri symbolizes the shattering of old orders and the dawn of a new balance between Heaven and Earth.

Raja Mahakuli Mahatissa

Raja Mahakuli Mahatissa personifies the mortal corruption that fuels Anula’s vengeance. As the architect of Eppawala’s destruction, he embodies arrogance, paranoia, and divine delusion.

His reign thrives on deception and violence, maintained by prophets and generals who exploit faith for power. Despite his grandeur, Mahatissa is ultimately hollow—a ruler who mistakes fear for loyalty and divine favor for destiny.

His seduction by Anula and subsequent death by her hand serve poetic justice, marking the end of an era of tyranny. Through him, the novel critiques the illusion of divine right and the dangers of rulers who weaponize religion to justify oppression.

Prophet Ayaan

Prophet Ayaan serves as the voice of false faith—the manipulative priest whose sanctity masks greed and cowardice. His involvement in the massacre of Eppawala and his complicity in Wessamony’s schemes expose the corruption within spiritual institutions.

Ayaan’s relationship with the raja is symbiotic: he legitimizes tyranny in exchange for influence. When Anula confronts him, his confession lays bare the unholy alliance between Heaven and Earth that sustains suffering.

His death by poison is both punishment and purification—a reclamation of divine justice by human hands.

Commander Dilshan

Commander Dilshan is a soldier shaped by obedience and ambition, embodying the violence of empire. His participation in the Eppawala massacre makes him an emblem of moral decay within systems of war.

Yet his later confrontation with Anula reveals a flicker of guilt, suggesting that even the instruments of tyranny can recognize their sins. Dilshan’s downfall serves as a reminder that accountability cannot be evaded, even by those who hide behind orders.

His presence throughout the story grounds Anula’s vengeance in human terms, emphasizing that cruelty is not only divine but deeply mortal.

Calu, Sohon, and Kama

These three Yakkas—Calu, Sohon, and Kama—form the fraternal circle around Reeri, each representing facets of lost divinity. Calu embodies reason and restraint, acting as Reeri’s conscience.

Sohon personifies grief and longing, a reminder of the emotional toll of exile. Kama, aligned with desire and vitality, bridges the gap between life and afterlife.

Together, they represent fragments of a broken pantheon seeking restoration. Their loyalty to Reeri and, later, to Anula, signifies the possibility of redemption even among the fallen.

Through their suffering and camaraderie, the novel humanizes the divine, portraying gods as beings shaped by love, loss, and choice.

Fate

Fate operates as both character and cosmic principle, guiding yet never controlling the paths of mortals and immortals alike. Unlike Wessamony or the Divinities, Fate is neutral—an embodiment of balance and consequence.

It neither punishes nor rewards but ensures that every act ripples through existence. Fate’s relationship with Anula is particularly profound; it recognizes her not as a pawn but as a co-creator of destiny.

In guiding her through the final battle, Fate redefines divinity as coexistence rather than dominance. It represents the ultimate lesson of Her Soul for a Crown—that destiny is not granted from above but forged by those who dare to act with both courage and compassion.

Themes

Vengeance, Justice, and the Price of Redress

Anula’s first decisions in Her Soul for a Crown are not framed as abstract moral puzzles; they are survival choices forged in the memory of Eppawala’s fires. What begins as a personal vendetta expands into a judicial ambition, as she shifts from killing one man to imagining a reordered realm.

The book keeps testing whether vengeance can transform into justice without reproducing the very cruelties it seeks to answer. Anula’s poisons are an art, a science, and a language: they let her speak in a palace that denies her voice.

Yet each dose also exacts a toll, pushing her closer to the tyrants she opposes. The confrontation with Prophet Ayaan crystallizes this tension.

She does not simply silence a hypocrite; she exposes the architecture of sanctioned slaughter and replies with a punishment that mirrors divine fire. The narrative refuses the comfort of a spotless avenger.

Anula’s path stains her hands, but it also pries open the machinery of impunity—false piety, spectacle, and bargains struck in sacred rooms to rationalize mass harm. When she later uses the Bone Blade to sever Death’s hand, the story reframes revenge as recovery: not only striking down the guilty, but restoring what can be restored and naming what cannot.

By the time she claims the throne, “justice” no longer equals the swift removal of enemies; it becomes the patient responsibility to prevent the next Eppawala. The price, however, is steep.

She forfeits simple innocence and accepts the burden of judgment, learning that the truest redress is not a final blow but a future in which no one must make her earlier choices.

Power, Gender, and the Making of a RaEjina

Power in Her Soul for a Crown arrives wearing jewels, masks, laws, and prayers—and it is frequently designed to keep women ornamental. Anula’s ascent exposes how femininity can be treated as currency inside a palace economy: beauty is audition, marriage is policy, and concubinage is a corridor to influence that ends in a locked door.

Against this architecture, her aunt Nirma offers a parallel institution—clandestine study circles, a hidden library, and a curriculum that treats poisons, history, agriculture, and rhetoric as tools of rule, not merely rebellion. The novel insists that queenship is not an accident of favor; it is a craft someone taught her to practice.

The title “raejina” is therefore not just a feminine counterpart to a raja; it signals a different theory of sovereignty. Anula learns to read rooms, debts, and the psychology of tyrants as precisely as she reads the potency of kaneru blossoms.

She manipulates ceremony when needed, then discards it when it becomes a cage. Even the wedding, staged to seal her subordination, becomes a rehearsal for public command.

The murder of the usurper with a poisoned kiss reverses the palace’s longest-running scam: the use of women’s bodies as guarantees for men’s legitimacy. Here, a woman’s body guarantees liberation instead.

Importantly, the crown she claims is not bestowed by a husband or a council; it is ratified by people rising to their knees in a battered hall after the storms break. Gender is not erased by that coronation; it is politicized.

The new reign must withstand the institutional memory of a court that has always preferred pliant consorts to governing queens, and the book’s final notes acknowledge that leadership will demand more than daring—it will demand sustained, public, disciplined rule.

Faith, Bargains, and the Morality of the Heavens

The sacred in Her Soul for a Crown is neither clean nor reassuring. The Divinities and Yakkas preside over a cosmos where petitions arrive steeped in pettiness and cruelty, and where heavenly lords use relics and rites to advance agendas that look disturbingly human.

Wessamony’s hunger for the Bone Blade exposes the hollowness of celestial exceptionalism: a god can persecute, deceive, and bargain like any usurper. Reeri, banished and guilt-ridden, complicates the picture further.

He is capable of tenderness and fury, of protection and mistake. The book therefore replaces binary theology with a politics of covenant.

Every prayer is a contract, every relic a clause, every ritual an enforceable term. Anula’s soul-offering is not a surrender of autonomy but the drawing of a boundary: help me take back my world, or I will find another path.

Later, when Fate itself halts time to allow reversals, the text introduces an authority beyond idols and tyrants—an order that watches the balance rather than any single petitioner’s triumph. In that meeting, faith becomes ethical courage rather than obedience.

The Heavens are not a vending machine for victory; they are a realm with costs, memory, and accountability. This view also indicts human institutions that borrow sacred language to authorize slaughter; Ayaan’s confession reveals how theology can be weaponized to normalize atrocity.

By the end, worship is recast as stewardship. Reeri’s acceptance of the Great Sword symbolizes a celestial office bound by service, not domination, and Anula’s destruction of the Bone Blade rejects shortcuts that circumvent communal responsibility.

Belief, in this world, is not the suspension of reason; it is the disciplined alignment of power with care.

Memory, Trauma, and the Work of Survival

The novel’s pulse is set by a child watching her homeland burn. Anula’s memory does not sit passively in the background; it instructs her breathing, her gait, the precise calm with which she opens vials and measures drops.

Trauma is represented as a ledger of images: molten silver forced down her father’s throat, her mother’s last command to “look away,” the morning after when soldiers arrive not as rescuers but as janitors of the massacre. Those images do not simply haunt her; they organize her understanding of safety and truth.

She learns that declarations from thrones can mean the opposite of what they claim, that processions and purifications can be camouflage for predation, and that promises from both priests and spirits can conceal opportunism. The book honors survival as an art requiring attention and improvisation.

Anula curates a mask of devotion because constant honesty in a violent court is a luxury the traumatized do not possess. Yet the narrative also gives her moments where memory does not only wound; it guides tenderness.

Her compassion for Premala originates in shared vulnerability, a recognition of how power squeezes confessions and compliance from those with no cushion against taxes or hunger. The later resurrection scene is not just spectacle; it functions as a counter-memory practice.

By cutting down Death’s hand and returning stolen lives, Anula asserts that history can be more than a record of what was taken. It can be amended through risk, song, and a blade used not to dominate but to repair.

Even then, the book refuses naive closure: she cannot retrieve her parents, and grief persists as a chamber within strength. Survival here is not forgetting; it is a commitment to act so that others’ children will remember a different morning.

Knowledge, Secrecy, and the Ethics of Poison

Hidden compartments, coded gatherings, and herb-laced recipes turn knowledge into contraband in Her Soul for a Crown. Nirma’s library represents a radical curriculum: women read banned treatises, study governance, and examine plant lore not as curiosities but as instruments of policy.

Poison is the most provocative “text” in this school. It dramatizes knowledge as something that can be used to rebalance a field where brute force and titles have long dictated outcomes.

The novel treats poisoning neither as villainy nor as romance; it treats it as a craft that forces hard ethical scrutiny. Anula’s early mistake with the guard’s tincture shows how intention and consequence can misalign, and her later precision demonstrates the moral obligation to master any tool one dares to employ.

The secret societies she encounters, particularly the Kattadiya, pose a second question: Is secrecy itself neutral? The Kattadiya claim to protect the realm, yet their rites preserve authority through fear and punitive spectacle.

Nirma’s circle, by contrast, incubates collective competence and political literacy. The juxtaposition suggests that clandestine knowledge is ethical only when it increases the community’s capacity to govern itself rather than terrorize dissenters.

The destruction of the Bone Blade at the end extends this ethic: even righteous actors should dismantle instruments that centralize reality-bending power in a few hands. Knowledge must circulate, be taught, and be answerable to those it affects.

Anula’s reign is therefore imagined as a republic of skill—apothecaries, healers, strategists, readers—rather than a monarchy of miracles. In that vision, a recipe can be as revolutionary as a sword, provided it is deployed with accountability and aimed toward shared flourishing.

Fate, Choice, and the Limits of Miracle

The story persistently tests whether destiny commands or invites. Prophecies and portents shimmer around Anula—the moving Makara beneath the cleansing pool, the blood-red mark that seals her bargain—yet she never surrenders the authorship of her actions.

Fate appears not as a puppeteer but as a witness with rules. When time stops and the Bone Blade sings, Anula is granted extraordinary latitude, but it is bounded by principles she cannot override: her parents cannot be restored, and the balance between realms must be preserved.

These constraints reshape the meaning of victory. Triumph becomes the discipline to accept limits while still choosing the most generous action available.

Her later decision to break the Bone Blade symbolizes a refusal to institutionalize miracle. The realm may need wonders in a crisis, but everyday justice requires processes that all can trust and repeat—courts that do not sell absolution, taxes that do not devour the poor, rituals that heal rather than terrorize.

Reeri’s own arc echoes this reframing. He ascends to lordship not through an irresistible script but through a sequence of acknowledgments: guilt recognized, kin embraced, power accepted as service.

Choice, then, is the grammar of fate. The cosmos marks and guides, but mortals must write the sentences that follow.

In practical terms, this means Anula’s sovereignty will be measured less by dramatic rescues than by the routines she sets—the harvest schedules, the punishments she refuses to normalize, the alliances she forges without sacrificing her people’s dignity. Miracles open doors; policy keeps them open for those who come after.

Love, Solidarity, and the Reimagining of Bonds

Romance in Her Soul for a Crown is not a detour from statecraft; it is an examination of how bonds can be made equal under pressure. Anula and Reeri share attraction, anger, confession, and revised vows.

Their connection matures only when both relinquish entitlement: she refuses to be a vessel for celestial ambition, and he refuses to treat her soul-offering as a permanent lien. Consent is renegotiated several times, and trust is earned in scenes of study, mourning, and tactical debate rather than only in embraces.

The book also widens the lens to friendships and comradeship. Premala’s journey from frightened maid to guruthuma embodies solidarity as protection that does not demand secrecy as a tithe.

Bithul’s steadiness anchors campaigns that might otherwise collapse into spectacle. Even the kneeling of the crowd after the storm is written not as adoration of a savior, but as a pledge of shared responsibility.

These bonds contest the palace’s oldest logic: that loyalty is either bought or coerced. Instead, relationships are forged through mutual risk and the willingness to tell unwelcome truths.

When Reeri returns under a compact that grants limited time on Earth, the narrative refuses the fantasy of limitless possession; love must adapt to seasons and duties. That arrangement clarifies the difference between hunger and care.

The former seizes and hoards; the latter honors boundaries and still chooses presence, again and again. In the end, bonds are the counter-relics of this world—portable, durable, and capable of repairing what weapons and wonders only temporarily address.

Death, Rebirth, and the Ethics of Restoration

The confrontation with Death’s proliferating hands offers the book’s clearest philosophy of repair. Resurrection is not gifted indiscriminately; it is accomplished through labor, song, and repeated, targeted cuts.

Each life returned is an argument about whose suffering matters, and the narrative insists that the answer must be: everyone within reach. Yet the refusal to restore Anula’s own family establishes a moral perimeter.

Restitution cannot erase all losses without unmaking the fabric of consequence; some absences must remain to protect the meanings of love, promise, and warning. Rebirth therefore occurs at several scales.

Individuals wake, a city stands, the heavens reorder their offices, and a new political era begins. But the text never imagines renewal as a reset to innocence.

Premala’s refusal to save Hashini from a poison of her own making is a hard lesson: mercy must not be commandeered to protect those who weaponize fear. The closing act—destroying the Bone Blade—converts restoration into governance.

By removing the shortcut of absolute power, Anula safeguards future resurrections of a quieter kind: seasons that return on time, granaries that refill, courts that correct errors, and festivals that celebrate lives not threatened by ritualized terror. Death remains part of the world, but so does a determined culture of aftercare: funerals that honor without lying, archives that record without sanitizing, and councils that plan so that hands like those in the cave need never be severed again.

Renewal, in this vision, is not the erasure of harm; it is the steady building of structures that keep harm from becoming policy.