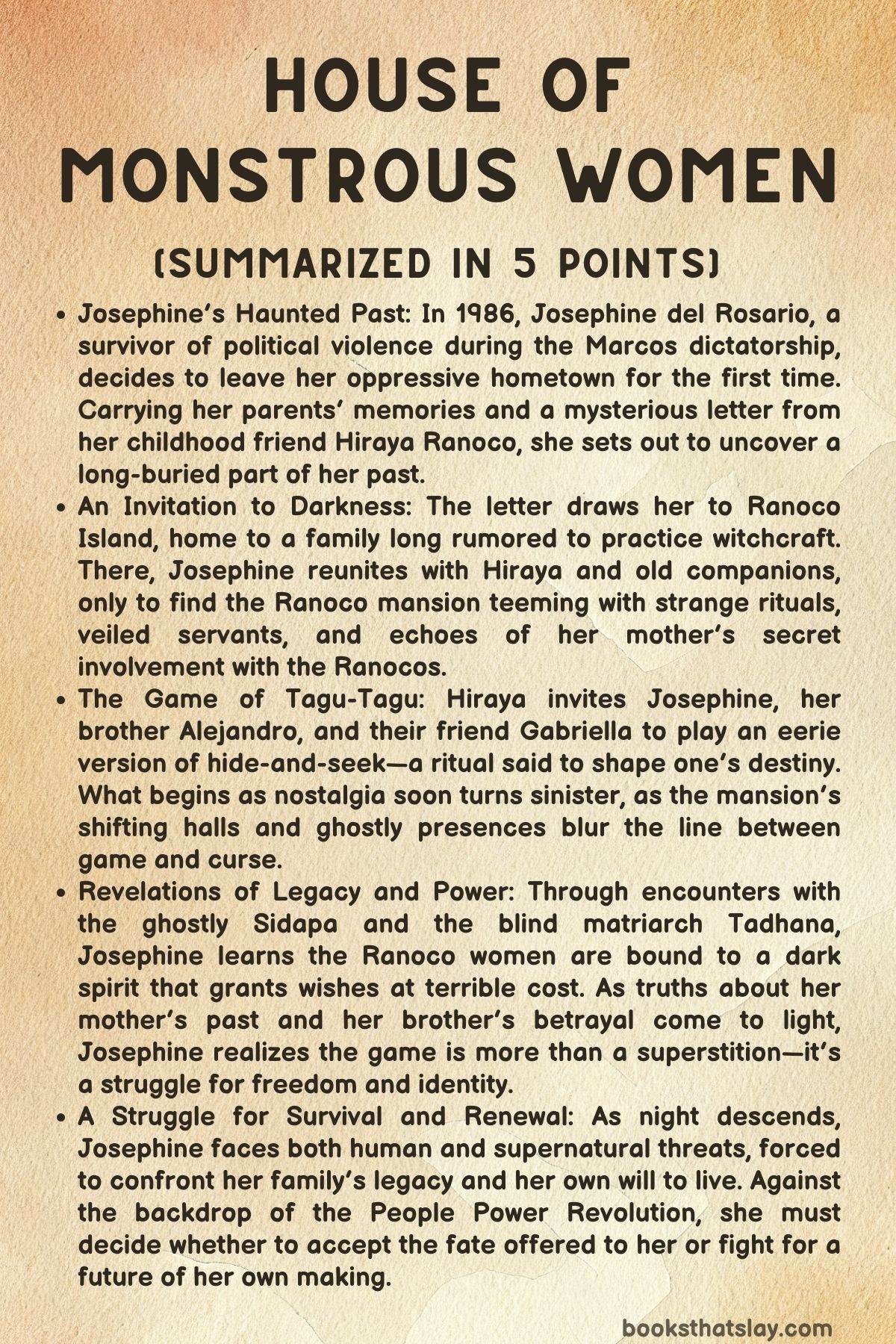

House of Monstrous Women Summary, Characters and Themes

House of Monstrous Women by Daphne Fama is a dark, atmospheric tale that blends political history, folklore, and gothic horror into a haunting exploration of power, trauma, and inheritance. Set against the turbulent backdrop of the 1986 People Power Revolution in the Philippines, it follows Josephine del Rosario, a woman scarred by her family’s political past and drawn into a mysterious reunion on an isolated island.

There, amid the eerie Ranoco mansion and its monstrous lineage, Josephine confronts ghosts both personal and ancestral. Fama’s novel examines how history, myth, and womanhood intertwine through generations cursed by the pursuit of freedom and control.

Summary

Josephine del Rosario lives in the small town of Carigara, carrying the burden of her family’s past. Her parents were murdered by forces loyal to dictator Ferdinand Marcos after her father opposed a corrupt local mayor, Eduardo Reyes.

Eleven years later, Josephine has grown into a quiet, isolated woman, branded by her family’s disgrace. As the People Power Revolution begins to challenge Marcos’s regime, she decides to leave Carigara for the first time in years.

Clutching her late father’s suitcase and wearing her mother’s emerald gown, she boards a jeepney bound for Biliran, summoned by a mysterious letter from an old childhood friend—Hiraya Ranoco. The letter promises Josephine a chance to reclaim the future she once desired if she plays their old childhood game again.

The Ranocos were once an enigmatic family rumored to practice witchcraft. Years ago, a fire destroyed their home, and they vanished from town.

Now, Hiraya’s invitation rekindles Josephine’s long-suppressed curiosity and nostalgia. On the way to Ranoco Island, Josephine reflects on their shared childhood, remembering the peculiar version of hide-and-seek they played called tagu-tagu—a ritualistic game that always felt more like an initiation than mere play.

She recalls Hiraya’s withdrawn sister Sidapa and their aunt Tadhana, a blind seer who had shared a secret bond with Josephine’s mother. Despite her mother’s public scorn of the Ranocos, Josephine had often seen her seek Tadhana’s guidance under moonlight, revealing layers of hypocrisy and fear.

Arriving at Kawayan, a nearby fishing town devastated by poverty, Josephine takes a small boat to Ranoco Island. As she approaches the mansion, memories of the past come rushing back—of the night Hiraya and Sidapa had appeared at her gate, burned and trembling after their home caught fire.

That was the last time Josephine saw them. The rebuilt Ranoco mansion now looms like a creature from myth, its windows glinting like eyes, surrounded by ancient balete trees said to house spirits.

Inside, Josephine reunites with Hiraya, now beautiful but scarred, missing one eye. Their joy is immediate but uneasy.

Within the labyrinthine halls, Josephine meets her brother Alejandro and their friend Gabriella Santos, both summoned by Hiraya’s invitation. The reunion quickly turns tense.

Alejandro, once politically ambitious, now carries bitterness and scars from Manila’s struggles. Gabriella tries to mediate as Hiraya proposes they all play a new version of their childhood game—tagu-tagu.

It will, she claims, determine who can claim control over their destiny. The group reluctantly agrees, not realizing how literal Hiraya’s promise will become.

As the game begins, Josephine becomes the hider, wandering through the vast, unsettling house filled with religious relics and insect displays. The Ranoco mansion feels alive, shifting as she moves.

She soon encounters Sidapa, appearing unchanged since childhood but ghostly and burnt. Sidapa warns her that she should never have come—that the Ranoco house is a trap, and that Hiraya’s promises lead only to ruin.

Before Josephine can learn more, Sidapa disappears, leaving behind only her mask.

Later, Hiraya gathers everyone for a grand banquet attended by masked servants. The feast is sumptuous but disturbing, the air thick with unspoken tension.

During the meal, Hiraya explains that tagu-tagu is an ancient ritual. The one who wins may shape their future as they desire.

Alejandro is drawn to the idea, desperate to resurrect his political dreams. Josephine, haunted by her losses, sees it as a chance to reclaim her family’s honor.

Yet, as the radio reports on the revolution brewing in Manila, the group’s laughter feels hollow.

That night, Hiraya leads Josephine into a secret garden at the mansion’s core, lush and perfumed, watched over by a fountain depicting the nymph Daphne turning into a tree. There, Hiraya reveals the truth behind the game: it is a ritual of power, inherited through generations of Ranoco women.

The winner’s heart’s desire is granted, but at a cost. Josephine learns that her own mother once played and won, explaining her sudden rise and mysterious bond with Tadhana.

The revelation ignites Josephine’s determination to play. She believes winning could restore her family’s lost future.

The next day, Josephine confronts Alejandro at the island’s cliff. He confesses his political failures and reveals that he has sold their ancestral home and even arranged Josephine’s marriage to a doctor for her protection.

Heartbroken and furious, she realizes that only by winning the game can she reclaim control over her own life. She begins exploring the mansion, uncovering its history and horrors.

She finds Sidapa’s prison—a charred room where Sidapa was once chained and tortured by her family after she tried to burn the house. Sidapa’s ghost admits she was blinded and abused by her mother and sister, and warns Josephine again: no one escapes the Ranoco curse alive.

When Josephine later faces her brother again, their confrontation is interrupted by Hiraya and the matriarch Tadhana. The old woman announces that the ritual will begin at dusk.

Each participant must draw lots—Hiraya will hunt Gabriella, Alejandro will hunt Josephine. The “aswang” or hunters must kill their prey before dawn, while the hunted must survive or reach Sanctuary.

The servants seal the mansion as Hiraya sings the rhyme that begins the deadly ritual.

Josephine flees with Gabriella as the house transforms—its corridors twisting, its servants turning feral. They separate to improve their chances.

Josephine encounters Hiraya again in a hidden garden. Hiraya confesses everything: her family is bound to a spirit called the Engkanto, which feeds on them and turns them into monsters.

Sidapa’s rebellion and suicide had been her attempt to break the curse. Now Hiraya herself carries the demonic seed that sustains the curse.

She warns Josephine that Alejandro, now tainted by the same darkness, will be compelled to hunt her. Despite the horror, Josephine and Hiraya promise to survive together, sharing a fleeting moment of tenderness before parting.

Guided by Sidapa’s ghost, Josephine learns that the Sanctuary lies not within the mansion but in the cave beneath the cliffs. On her way there, she finds Gabriella and saves her from Hiraya, who is attempting to pass the cursed seed to her.

To protect them both, Josephine accepts the seed herself, taking the burden into her body. When Alejandro, now possessed, finds her, Hiraya sacrifices herself to buy Josephine time.

Josephine escapes through the mansion’s collapsing halls and descends into the underground cave. There, she discovers the monstrous truth: an enormous balete tree, fed by generations of Ranoco women, their bodies absorbed into its roots.

At its base, Tadhana has transformed into a grotesque, insect-like creature. She attacks Josephine, declaring that the curse must continue through her.

Josephine fights back, stabbing the creature and wounding it. Alejandro arrives, briefly freed from possession, and together they destroy the cursed fruit that sustains the Engkanto.

The spirits scream and dissipate, but Alejandro dies in Josephine’s arms, freed at last.

Sidapa’s spirit then reappears, nailed to the tree. She forces the seed out of Josephine, swallows it herself, and demands that they burn her and the roots to end the curse.

Josephine and Hiraya obey, setting fire to the tree as dawn breaks. As the Ranoco mansion burns and the radio announces Marcos’s fall, the curse dies with it.

Years later, in 1991, Josephine, Hiraya, Gabriella, and Gabriella’s twin daughters visit the family mausoleum on All Saints’ Day. Gabriella wears Alejandro’s ring, symbolizing the unity that has survived tragedy.

Eduardo Reyes has grown old and powerless, and the women—once bound by history, politics, and curses—have reclaimed their lives. Through fire, death, and defiance, they have finally escaped the house of monstrous women.

Characters

Josephine del Rosario

Josephine is the moral and emotional center of House of Monstrous Women, a woman marked by inherited grief and small-town surveillance who slowly reframes her “political orphan” stigma into self-authorship. At first, she carries her parents’ memory like a duty that keeps her immobilized—tending the decaying house, absorbing gossip, and practicing a self-erasure that feels safer than desire.

The invitation to Ranoco Island activates the parts of her that survived the massacre: curiosity, stubbornness, and a latent hunger to choose her fate. In the haunted house she becomes a cartographer of danger—mapping corridors, parsing rules, and testing loyalties—until strategy hardens into courage.

Her tenderness with Hiraya sits beside a flinty refusal to be traded as a dowry or bound to an inherited curse; love does not blunt her clarity. Taking the seed to spare Gabriella shows her instinct to interpose her body between harm and others, but it’s also a reclamation of agency: if a monstrous history demands a vessel, she will decide how that story ends.

In the cave, rejecting the spirits’ offer to inherit the house is Josephine’s final refusal of both Marcos-era fatalism and Ranoco determinism. She chooses freedom that costs, rather than power that cages.

Alejandro del Rosario

Alejandro is Josephine’s volatile mirror: charismatic, wounded, politically ambitious, and easily seduced by grand narratives that promise to convert trauma into purpose. He embodies the post-dictatorship Filipino male who wants to avenge history through public victory yet neglects private responsibility.

His plan to marry off Josephine is both betrayal and confession; he is desperate enough to barter love for security. Under the house’s influence he becomes the literal hunter, his body commandeered by a chorus of spirits—an image of how authoritarian power colonizes individuals.

Yet he is not reducible to monstrosity. In the cavern, the flicker of recognition as he whispers how to destroy the fruit reveals the brother who remembers tenderness before ideology.

His death is tragic but purgative: he refuses the house’s reward, participates in breaking the core, and returns Josephine’s future to her, transforming from threat into ally at the cost of his life.

Hiraya Ranoco

Hiraya is seduction and sorrow braided together, a woman raised to be a shrine who longs to be a door. Scarred, one-eyed, and luminous, she inherits a matrilineal vocation she never chose, taught that love must be weaponized and intimacy is a ritual of extraction.

Her invitation to Josephine is both gambit and plea, a hope that someone from outside the lineage can interrupt the cycle. Hiraya’s tenderness is real—her joking bravado, her “sister for the night,” the kiss under lightning—yet she is also capable of devastating pragmatism, nearly passing the seed to Gabriella to survive.

That contradiction is the point: she is a survivor shaped by a house that confuses devotion with sacrifice. When she transfers the seed to Josephine at Josephine’s insistence and then risks herself to stall Alejandro, we see the person she wishes to be outrunning the monster she was made to serve.

At the end, escaping with Josephine is not a fairytale exit but an ethical turn: she chooses to be partner, not priestess.

Sidapa Ranoco

Sidapa is memory given flesh, the novel’s conscience in ash and honey. As the child punished for resisting the imposed “mother” role, she is the truth-teller who appears with soot-blackened feet to insist that the game is not mythology but machinery.

Her accusations—of starvation, shackling, and the gouging of her eyes—reveal how the family dresses violence as ritual. As ghost and crucified body within the subterranean balete, Sidapa exposes the house’s economy: women fed to a lineage so that the lineage may feed.

Yet her final acts—guiding Josephine, demanding the seed, ordering them to burn her and the tree—recast her from tragic victim to liberator. She refuses to let her suffering be the last word; she makes it the fuse that ends the cycle.

Tadhana (the Aunt/Seer)

Tadhana is institutional power in human form: blind not as lack but as function, a will that refuses any sight but its own prophecy. She manipulates piety, folk healing, and matrilineal authority to engineer obedience, reducing girls to roles—seer and mother—as if destiny were a ledger.

Her banquet, laced with tainted honey, is political theater, transforming guests into instruments while calling it tradition. In the cavern, her metamorphosis into a chimeric insect is not a surprise but a revelation of essence: she has always been the hive’s queen, suturing herself into the living tree to keep the economy running.

Her downfall—pierced, resewn, and finally burned—marks the end of a theology that sanctified predation.

Gabriella Santos

Gabriella is the novel’s skeptic and ballast, a woman with enough love to soothe and enough steel to fight. She joins the island with political arguments in her mouth and a private grief she refuses to sentimentalize.

Her near-fatal confrontation with Hiraya—blade at the throat—shows a survivor’s logic: she will wound to live. But her willingness to be persuaded away from harm after Josephine intervenes, and her later partnership in the escape, reveal a capacious ethics.

In the epilogue, wearing Alejandro’s ring and raising daughters, she stands as the quiet thesis: endurance is not passive; it is work.

Eduardo Reyes

Eduardo represents the provincial face of authoritarianism—once lean and ruthless, now bloated yet still parasitic. He is the man who won unopposed because opposition was murdered, the enduring shadow in the plaza whose gaze keeps communities small.

The epilogue’s note that he is diminished after the revolution underscores the book’s political horizon: monsters of the state can be starved when collective power shifts, but they do not vanish without sustained refusal.

Doctor Roberto Uy

Roberto is patriarchy styled as benevolence, the suitor who weaponizes care into entitlement. His “protection” is a dowry contract that treats Josephine as a solvency instrument, a private echo of public strong-arming.

He is not the primary villain, but his presence clarifies the stakes: even outside cursed mansions, women are traded under the language of safety. Josephine’s rejection of him is therefore part of the same arc as burning the tree.

Josephine’s Mother

Josephine’s mother is the bridge between town respectability and Ranoco occult power, a woman who publicly condemns what she privately seeks. Her rumored victory in the ancestral game suggests complicity born of desire for upward movement—marriage, fortune, protection.

She embodies the compromises demanded by Marcos-era survival and by patriarchal respectability politics: to be safe, you must be chosen; to be chosen, you must yield. Josephine’s life becomes a reckoning with that inheritance, choosing exposure over secrecy and solidarity over transaction.

Themes

Political Terror and Collective Amnesia

Carigara’s gossiping plaza, the unopposed victory of Eduardo Reyes, and the long shadow of the Marcos regime establish a civic landscape where fear becomes routine and forgetting becomes survival strategy. Josephine is labeled a “political orphan,” yet the town’s language bleaches the violence from history; her parents were not simply lost, they were massacred, and the community’s refusal to keep those facts bright is a second injury.

The plaza chatter, Roberto’s tut-tutting concern, and Eduardo’s smug gaze show how a dictatorship’s habits persist at the level of daily manners. Memory itself is dangerous capital: to carry it openly, as Josephine does in her mother’s emerald gown and her father’s suitcase, invites scrutiny; to misplace it, as the townspeople do, smooths one’s livelihood but mortgages the future.

The novel’s temporal hinge—February 1986—matters because radio reports of cheating and uprising puncture the fog of communal silence and relocate memory from the private realm into public debate. Yet even as Manila broadcasts the nation’s awakening, the island of Ranoco rehearses the old politics with new costumes: sealed doors, armed servants, and a ritual that turns neighbors into quarry.

The game is a miniature of a rigged state—rules written by a matriarchal clique, enforcement outsourced to masked functionaries, rewards promised to keep the desperate compliant. When Josephine refuses the house’s inheritance and burns the mother tree, the act counters the local habit of swallowing truth.

In place of rumors and euphemisms, fire renders the past legible. The final visit to the mausoleum confirms that remembrance, not simple victory, is the endgame; the family’s survival depends on narrating what happened without trimming the edges that make the story painful.

The House as a Living System of Power

The Ranoco mansion is less a setting than an organism that regulates desire, obedience, and fear. Corridors named for colors, capiz-shell eyes, and halls that shift under pressure reveal an architecture designed to condition movement and thought.

Each generation’s “divine inspiration” leaves alterations that do not beautify so much as capture, like the incremental fortifications of a prison where inmates become the engineers. The house surveils through insects, absorbs offerings through its roots, and organizes labor through veiled servants whose anonymity erases accountability; the spectacle of a banquet arrives already lacquered with coercion.

This system culminates in the subterranean balete tree—a vascular core that feeds on bodies, stores women as trophies, and drops glowing fruit as instruments of succession. The environment enforces hierarchy: foyer to hall, hall to court, court to altar, a gradient from civility to sacrifice.

Even the “sanctuary” sits outside, confirming that safety requires stepping beyond the property’s jurisdiction. Importantly, the mansion reproduces the logic of authoritarian states while wearing the ornament of tradition.

Rosaries hang beside ritual masks; rooms papered in Bible verses crawl with ants. Faith and folklore are not in conflict here; they are harnessed to the same control system, giving sacred alibi to domestic terror.

When Josephine maps the rooms and learns the timings of lanterns and guards, she practices a politics of spatial literacy, converting opaque ritual into actionable knowledge. Setting the orchard ablaze is an urban-planning revolt as much as a moral one: it disables the infrastructure that makes predation ordinary.

Afterward, the house’s absence becomes the new architecture; what remains is a civic space made of memory, graves, and the promise that inheritance will no longer be a corridor that narrows into a cave.

Monstrosity, Aswang Lore, and Gendered Otherness

Local rumor brands the Ranocos as witches and aswang, but the story refuses a flat binary of human versus monster. Monstrosity is manufactured, administered, and inherited through ritualized harm.

Tadhana forces Sidapa to carry a demonic seed; later, she attempts to stitch herself into the arboreal womb, seeking permanence through predation. Hiraya is not born monstrous; she is initiated, and her transformation is explained as duty—an echo of how patriarchy often clothes exploitation as tradition or sacrifice.

The aswang figure, long used to police women’s appetites and independence, is inverted. Josephine’s hunger is not for blood but for a life unassigned by men—first Eduardo’s regime, then Roberto’s proposal, then Alejandro’s transaction.

The novel turns the folk image outward to expose who benefits when women are named frightening: those who wish to keep their power. At the same time, monstrosity becomes a language for trauma’s physiological truth.

Hunger, heat, black smoke voices, and kerosene-scorched hands are somatic records. Alejandro’s temporary possession shows that the category is porous; men, too, can be conscripted into predation by the system’s diet of tainted honey, its music of orders and oaths.

What distinguishes the living from the monstrous is not anatomy but consent and care. Josephine’s refusal to let Hiraya expel the seed into Gabriella, her insistence on bearing the risk herself, marks a counter-ethic where power serves protection.

Sidapa’s final choice to swallow the seed and demand fire restores monstrosity to its source—a curse that can be ended only when the community stops treating women’s bodies as containers for inherited threats. In this light, the destruction of the orchard is less the killing of monsters than the funeral of a lie about what makes a monster in the first place.

Fate, Games, and the Ethics of Choice

Tagu-tagu is framed as a children’s pastime sharpened into ritual, but its real function is to teach that choice exists inside constraint. Lots are drawn, roles assigned, the house sealed; the resemblance to elections rigged by terror is unmistakable.

Yet within the closing jaws, Josephine keeps finding pockets of agency: mapping corridors, reading radio updates as time cues, trading routes for Gabriella’s screams, turning a ledge into a staircase, and a fruit knife into a political instrument. The ritual promises a wish to the victor, a seductive narrative that privatizes destiny by steering desperate people into competition.

Alejandro wants a future financed by the game’s prize; his pursuit of public office becomes tethered to a private lottery, and in that tether lies the critique. Regimes maintain themselves by convincing citizens that the only way out is through the structures that keep them trapped.

Josephine’s crucial decision is not merely to survive until dawn; it is to reject the prize when the house finally offers it. She will not inherit the engine of harm or exchange liberty for a personalized miracle.

The scene in the cavern clarifies the cost of victory: to win on the house’s terms is to agree that others may be bound to it. Alejandro’s moment of lucidity—naming the weak point at the fruit’s core—testifies that freedom emerges when players step outside the scoreboard and choose repair over ranking.

Even the romance between Josephine and Hiraya is staged as a refusal of the game’s logic: partnership rather than conquest, promise rather than prize. By the end, choice has been rescued from fate by reimagining the rules, refusing the reward, and writing an alternative contract authored by the living.

Family, Debt, and Betrayal

Kinship, in this story, is not sentimental shelter but a ledger written in favors, dowries, and obligations that often migrate into betrayal. Alejandro’s arrangement of Josephine’s marriage to Roberto is couched as protection, yet it is also a sale of her time and body to stabilize his political ambitions.

The wordless years after the massacre create a vacuum where siblings project their own strategies for survival onto each other: Josephine preserves the decaying estate as an Ark of memory; Alejandro chases influence in Manila, insisting on a win that will redeem them both. Their conflict is heartbreaking because both responses are logical under terror, and both are incompatible.

The game forces their stances into literal opposition—hunter and prey—even as the story keeps testing whether another grammar of family is possible. Gabriella’s steady mediation, the dance that interrupts a fight, and the gifting of the mother’s ring after Alejandro’s death outline a kinship not measured by title or blood alone.

Hiraya’s plea for rescue and Josephine’s refusal to weaponize the seed against Gabriella show how the circle of care can expand beyond the surname. Sidapa’s history exposes the lethal underside of family as institution: discipline masquerading as love, starvation and shackling as pedagogy.

In choosing to set Sidapa free and to burn the roots that fed on daughters, Josephine rejects inheritance as debt and restores it as responsibility. The final mausoleum gathering reframes legacy as stewardship rather than possession.

What survives is not a house or a name but a pattern of mutual keeping—ring passed to Gabriella, twins alive, stories told without trimming—and a recognition that family loyalty without consent is only another word for control.

Religion, Ritual, and Complicity

Images of Catholic devotion and folk practice appear everywhere: the grotto offering, rosaries on the walls, a blind soothsayer who “purrs” only for Josephine’s mother, kitchens sweetened with honey that is anything but innocent. The novel refuses easy moral mapping where Church equals good and folklore equals evil.

Instead, it shows how both can be recruited by power. Public scorn of the Ranocos coexists with private consultations at night; a mother who dismisses Tadhana in daylight submits to moonlit baths for divination.

This oscillation is not mere hypocrisy; it is a portrait of a society learning to survive under overlapping authorities—state, family, and spirit. Tadhana performs the confidence tricks of oppressive leaders: redefining cruelty as tradition, calling mutilation initiation, and placing ritual above mercy.

The banquet’s blessings do not cleanse the food; they launder it. Even the radio, herald of revolution, becomes a liturgical drone in the mansion, a chant that measures time for the hunt.

Josephine’s offering of her mother’s ring at the grotto is a counter-ritual, not because it invokes a purer magic, but because it is voluntary and directed toward protection rather than power. By the cave, where altar merges with geology, the theology of the house finally reveals itself: salvation as obedience, eternity as captivity.

Josephine’s response—stabbing the creature who preaches inevitability, rejecting anointment as successor, and burning the holy grove—constitutes a reformation enacted in one night. What remains afterward is not an absence of faith but a redistribution of it: trust placed in promises kept among friends, in the slow work of mourning, and in a civic future that does not require anyone’s eye, womb, or labor as sacrament.

Bodies, Autonomy, and Sacrifice

From the first page, bodies are used as messages. The emerald gown repurposes Josephine’s mother’s elegance into armor.

Sidapa’s blistered hands reek of kerosene, a sign that resistance has a smell the town refuses to acknowledge. The Ranoco legacy is literally tactile—honey pressed into mouths, eyes removed to open a second sight, a seed passed throat to throat.

Against this choreography of intrusion, Josephine claims the right to decide what her body will carry and when. She accepts the seed not as submission but as strategic custody, a temporary holding that prevents harm to Gabriella and buys time for a better ending.

Consent reorganizes the meanings of pain; her choice converts a weapon into a bridge. The novel is careful to separate sacrifice chosen from sacrifice demanded.

Tadhana’s theology requires offerings; Sidapa’s final act requires a funeral. The difference is everything.

When Sidapa orders them to burn her and the mother tree, she is not valorizing self-destruction; she is ending the economy that priced her body as fuel. Alejandro’s ruined face and final whisper show that autonomy is not only a women’s issue here; the regime colonizes any body it can feed.

Yet the narrative centers women because their bodies are the archive and the battlefield—sites where lineage, fear, and hope are negotiated. The epilogue’s image of children at the mausoleum is the antidote: bodies that do not need to be pledged to a house or a cause to be worthy of a future.

Autonomy, finally, is written as continuity without coercion: a life where rings signify love rather than purchase, where scars record survival rather than ownership, and where a kiss in a storm is not a prelude to ritual but a promise of ordinary days.

Revolution as Counter-Spell to Private Tyranny

While Manila counts crowds and announces the flight of a dictator, the island fights its own campaign. Radios report cheating and uprising as if reading stage directions for the night in the mansion.

The correspondence is exact without being didactic: authoritarianism relies on ritual and spectacle, whether it wears a sash of office or a veil of mourning. Eduardo’s weight and leer, the doctor’s paternalism, and Tadhana’s liturgy belong to the same grammar of rule.

The novel proposes that national change must be accompanied by domestic change, or the old habits will simply move indoors. Josephine’s journey traces that proposition.

She boards the jeepney, offers the ring, crosses the water, and steps into a space where the ballot box has been replaced by lots, and the precinct captains by masked servants. Her answer is to refuse both the counterfeit choice of a fixed game and the sweetened poison of a corrupt feast.

Burning the orchard aligns with the moment when the country chooses to remember the dead and name the guilty; the public announcement of Marcos’s fall arrives as dawn after a night of pursuit and bargaining. The survivors’ return to the mausoleum in 1991 completes the parallel: democracy is not an event but a maintenance practice, like sweeping graves and telling the children what the adults were once too frightened to say aloud.

In this frame, House of Monstrous Women reads as a manual for unlearning obedience. It argues that revolutions worthy of the name do not stop at the palace gate; they enter the home, the body, and the secret room where rules are made, and they change who gets to write them.