I Know How This Ends Summary, Characters and Themes

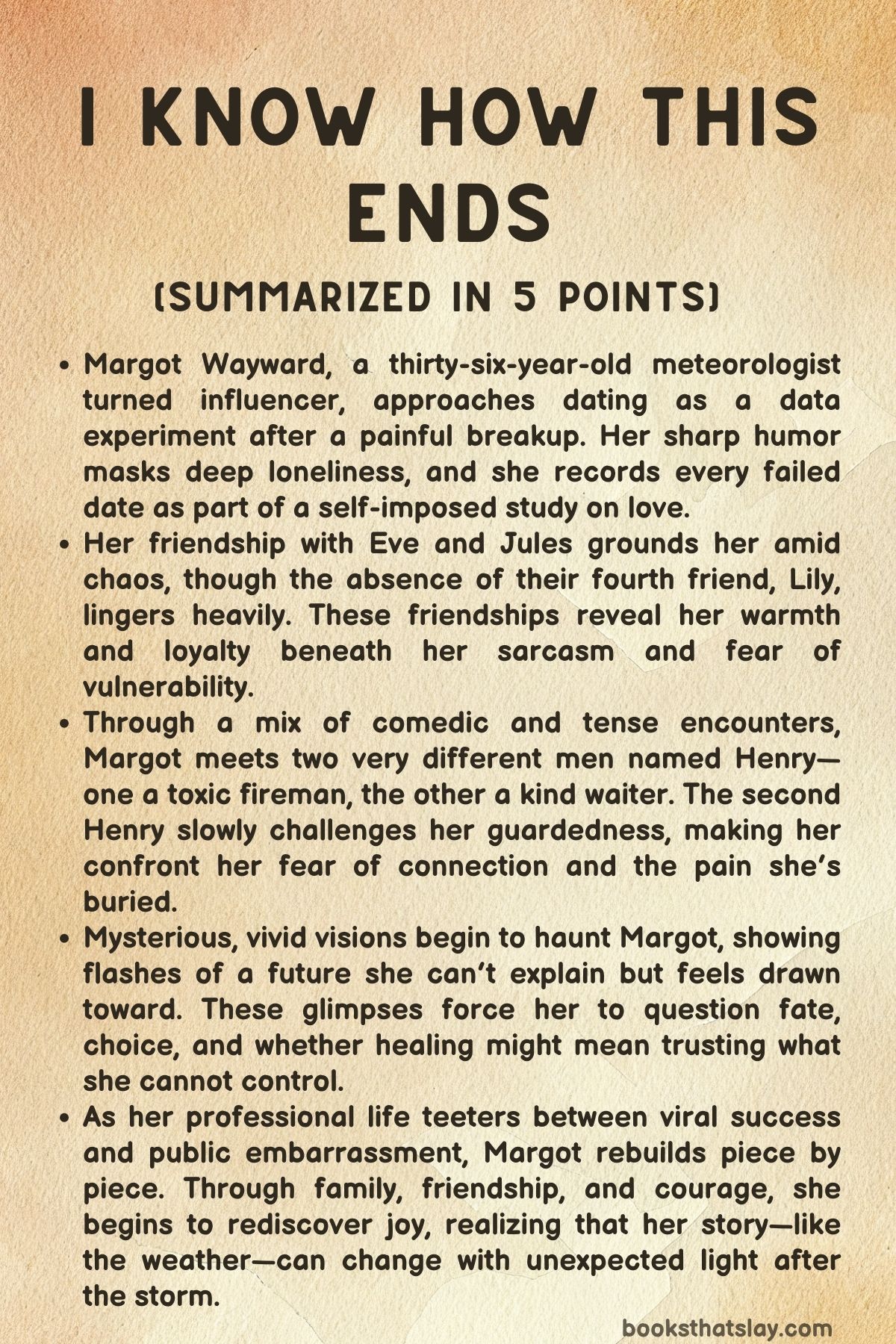

I Know How This Ends by Holly Smale is a contemporary novel that blends humor, romance, and introspection to explore love, grief, and the unpredictability of life. It follows Margot Wayward, a 36-year-old meteorologist whose scientific precision contrasts sharply with the emotional chaos of her personal life.

After a painful breakup and career shift, she approaches dating as a structured experiment—twenty first dates to prove she’s trying. Yet what begins as an analytical quest turns into a journey of self-discovery, friendship, and reconnection. Smale’s storytelling captures the awkward hilarity and quiet heartbreak of modern relationships, ultimately revealing how control and surrender coexist in the pursuit of love.

Summary

Margot Wayward, a thirty-six-year-old British-Australian meteorologist living in Bristol, is reeling from a breakup and a sudden career change. Once the chief meteorologist at the Met Office, she’s now an online influencer known as @MargotTheMeteorologist, making viral weather videos that sustain her financially but leave her isolated.

Determined to rebuild her life methodically, Margot designs an experiment: she will go on twenty first dates, treating each as data to analyze love and human behavior. Her “test environment” is always the same restaurant, Pasta La Vista, where she endures a parade of mismatched partners and disappointment.

Her latest bad date, a smug married man named John, ends with her humiliating him before leaving with her dignity intact. Margot documents the encounter in her growing list of dating disasters.

Back home, she scrolls through new profiles and arranges a meeting with a seemingly decent fireman named Henry. Though exhausted by loneliness and the performative nature of her online persona, she pushes forward.

Her life is a constant balancing act between her digital success and personal emptiness.

Margot’s emotional anchors are her best friends Eve and Jules, who have been with her since childhood. Together they support Eve through yet another round of IVF treatments, a moment that reminds them of the fourth member of their former group—Lily, whose absence remains painful.

Later, Margot calls her parents in Australia, enduring her mother’s nagging about settling down and her father’s awkward affection. Beneath her sarcasm lies deep grief for Aaron, the fiancé she lost eight months earlier under unclear circumstances.

When she meets Henry the fireman, the date begins well—he’s charming and attentive—but ends in disaster. His behavior shifts from kind to controlling when she offers to pay the bill, revealing a hidden misogyny.

Margot calmly ends the evening and covers the cost herself. The restaurant’s waiter, who has served her during all her Monday dates, teases her gently and flirts, revealing his own name—also Henry.

Margot feels a strange déjà vu after noticing blue letters marked on his hand, a detail she’s inexplicably seen before in a vivid vision. Against her own logic, she agrees to go out with him.

Her emotional landscape becomes more complicated. The first Henry begins sending her abusive messages, while Margot obsesses over Lily, now a glamorous influencer engaged to Aaron.

Her envy drives her to stalk Lily’s posts secretly until her friends confront her at a spa, urging her to let go of the past. During the outing, Margot experiences another strange flash—a vivid vision of her and the waiter Henry driving together, laughing.

When she regains consciousness, she’s shaken but intrigued. Henry messages her that night, and she agrees to meet him again, unaware that these visions are hints of something deeper.

Their next meeting starts awkwardly but soon feels natural. Henry’s kindness and wit disarm her, and he reveals he’s been observing her all along during her many visits.

He remembers her quirks, her compassion, even her guilt about her grandfather. Just as she begins to relax, Margot sees an online announcement: her ex, Aaron, is engaged to Lily.

Overcome by betrayal, she flees the restaurant, breaks down in the street, and later sets fire to her belongings in a cathartic act of destruction. The next morning, feeling hollow yet lighter, she throws herself back into work, even filming a humiliating ad for a fake rainwear company just to make ends meet.

Visiting her grandfather soon after, Margot discovers he’s nearly blind but has hidden it from her. While helping him, she’s struck by another vivid vision—painting a lilac room with Henry, sharing domestic bliss.

The experience frightens her, and she confides in her grandfather, who advises her to make amends with Henry. When she does, Henry forgives her easily, revealing his own pain: his wife, Amy, died of cancer, and he’s been single ever since.

Their connection deepens, though Margot is unnerved when her earlier vision seems to match details of his real life. She wonders if her visions might be glimpses of the future.

Despite fear, she allows the relationship to grow. Eve and Jules confront her about her self-sabotaging tendencies, and she finally admits she wants happiness but doesn’t know how to trust it.

Later, Henry calls her, and she confesses everything about Aaron’s betrayal and her emotional paralysis. Henry listens with compassion, comparing her to someone waiting at a bus stop for a ride that may never come.

Their mutual honesty rekindles hope. But soon, Margot’s career implodes when the fake brand she promoted turns out to be a scam, costing her reputation and sponsors.

A kind neighbor, Polly, steps in to help her rebuild, marking a quiet turning point in Margot’s support network.

Margot’s bond with Henry strengthens. She visits her grandfather again, helps him reconnect with family in Australia, and experiences more “future flashes.” One shows her and Henry arguing but resolving it with laughter, teaching her that love can exist alongside imperfection. She and Polly begin developing a pitch for a children’s weather show, Weather or Not.

Meanwhile, she agrees to babysit Henry’s daughter, Winter, when he must work unexpectedly. Winter is defiant at first, but Margot’s patience and humor win her over.

Together, they visit the oak tree where Winter’s mother’s ashes rest—a deeply emotional moment that cements their bond. By the time Henry returns, Margot has become part of his world.

Soon after, Margot falls ill, and Henry nurses her through it, proving his devotion. When she recovers, she uncovers Polly’s husband’s infidelity but hesitates to tell her.

Her career proposal gains momentum, and she feels genuinely content for the first time in years. Yet her visions intensify.

In one, she sees her own wedding to Henry, surrounded by friends and a child named Gus. The happiness feels real, but it’s followed by another vision years later—an older Margot and Henry, divorced but amicable.

Shaken, she interprets it as a warning that their love ends in heartbreak. Terrified, she breaks up with Henry preemptively to spare them both pain.

Months later, Margot’s life stabilizes. Her TV show succeeds, she reconciles with Lily, and Eve becomes pregnant.

When she realizes her beloved grandfather is dying—the person from her earlier “funeral” vision—she rushes to see him. He reveals that their family has a history of foresight and that visions are fragments, not fixed truths.

He encourages her to live fully despite knowing that endings are inevitable. Empowered, Margot seeks out Henry, confesses everything about her visions, and asks for another chance.

He proposes a pact: they’ll face the future together, choosing love without fear.

Fifteen years pass. Margot has become a beloved television presenter, and she and Henry have parted amicably after long years of shared life.

One day, wearing her pink coat, she walks through the same Bristol street from her visions and meets Henry again. Their daughter Winter, now grown, watches as they share a quiet, knowing moment—no tragedy, no regret, just mutual recognition.

The story closes with Henry saying it’s his turn to know what comes next, suggesting that life’s uncertainties are not to be feared but embraced, one moment at a time.

Characters

Margot Wayward

Margot is a thirty-six-year-old meteorologist turned creator whose voice fuses sharp observational humor with a guarded tenderness. She frames her love life as an experiment—twenty first dates in the same restaurant, careful notes, repeatable conditions—which lets her hide grief and fear behind method and metrics.

The summaries reveal a woman who uses data, wit, and self-deprecation to keep intimacy at bay after the betrayal by Aaron and Lily, yet whose strange, lucid visions force her to confront what control can and cannot guarantee. Her arc bends from cynicism and self-sabotage—flame-outs, literal bonfires, and the mantra that she is the red flag—toward vulnerability, care work, and authorship of a future she chooses rather than measures.

As she tends to her grandfather, mentors Winter, rebuilds a career, and risks reconciliation, Margot learns to treat uncertainty the way a meteorologist treats weather: not as failure of prediction but as the natural condition for living.

Henry Armstrong

Henry, the waiter who becomes Date Seventeen, is the quiet counterpoint to Margot’s defensive irony: patient, observant, and radical in his steadiness. He has tracked her kindnesses across months—apologies to staff, small generosities, nervous tells—making him the narrative’s witness and a subtle corrective to her self-story that she is unlovable.

A widower who avoids confrontation until love requires it, he offers a partnership ethos of going slowly, naming fears, and trying again; even his idea of the bus theory reframes Margot’s stasis without shaming it. The time-slip thread binds him to Margot’s visions—car interiors, jacket patches, domestic scenes—so that he becomes both a present-tense companion and a horizon line she keeps seeing and fleeing.

His dignity in heartbreak, his caregiving during her illness, and his pact to face the foretold ending together make Henry the book’s argument that love is not proof against endings but a practice of meeting them.

Fireman Henry

Fireman Henry functions as an early test case that exposes the limits of Margot’s experimental optimism and the cultural scripts that police women’s choices. He arrives charming and attentive, then reveals a brittle entitlement when the bill comes, using chivalry as a lever for control and contempt.

His subsequent barrage of angry texts does not just characterize him; it sharpens the book’s attention to misogyny disguised as romance and clarifies why Margot built guardrails around dating. By placing him adjacent to the waiter Henry, the story contrasts coercive certainty with generous attention, and it shows Margot beginning to separate red flags from her reflex to label herself the problem.

Eve

Eve is the ballast of the long friendship: pragmatic, warm, and resilient in her pursuit of motherhood. Her embryo transfers and eventual pregnancy anchor the book’s motif of persistence, while her tough love toward Margot—calling out the stalking, the isolation, the excuses—gives permission to change without demanding perfection.

Eve’s classroom call-in and later joy are moments where the social world repairs what betrayal fractured, reminding Margot that futures are communal work. Naming her son Augustus becomes a hinge for Margot’s crucial realization about her grandfather, showing how Eve’s story catalyzes Margot’s courage to act.

Jules

Jules embodies the messy, fallible middle ground of friendship: loyal for decades yet compromised by secrecy and proximity to Lily. Her withholding—knowing about the affair before Margot—ruptures trust and exposes how silence can be a form of betrayal even when motivated by conflict-avoidance.

The pub scene and its fallout force Margot to test a hard boundary, and the later partial repair underscores that reconciliation requires new terms, not a return to the past. Through Jules, the book examines whether intimacy can survive competing loyalties and what accountability looks like among equals.

Lily

Lily travels the longest moral distance, from the shimmering surface of a lifestyle feed to the humiliating depth of contrition. Her affair with Aaron detonates the friendship quartet, yet the story refuses to freeze her in that worst moment; she apologizes without self-exoneration, recognizes Margot’s anonymous kindness, and accepts limits when Jules refuses bridesmaid duties.

Lily’s arc converts Margot’s doom-scroll envy into a meditation on compassion and the difference between performance and personhood. By the time coffee is offered, Lily is no longer the rival who stole a life but a mirror in which Margot recognizes her own capacity to be generous without forgetting.

Aaron

Aaron is the catalyst antagonist whose betrayal sets the experiment in motion and haunts its early phases. He represents a story Margot inherited about herself—that she is too much, not maternal, not enough—and his swift proposal to Lily turns private loss into public spectacle.

Margot’s later confrontation with him is deliberately anticlimactic: she dismisses him so she can speak to the women, signaling that the true conflict was never the man but the wounds among friends. In function, Aaron is weather rather than climate: a storm that reveals the house’s weak points but does not define the season.

Grandad

Grandad is the book’s moral north and its quiet strand of magic, the one who shows Margot that foresight is not fate. His declining eyesight, chaotic house, and gentle quips ground the story in ordinary care, while his hinted Weyward ancestry reframes the visions as inheritance rather than anomaly.

He teaches by story rather than decree—the figurine that still breaks, the admission that glimpses are fragments—guiding Margot from control to courage. His blessing of Henry and Winter, and the small ritual of the toy panda, convert prophecy into praxis: love someone now, knowing endings will come.

Winter

Winter is both child and future tense: suspicious gatekeeper, grieving daughter, and later the adult who remembers. Her initial defiance cracks open into play and confession at the oak where her mother’s ashes lie, making her scenes some of the book’s most tender confrontations with loss.

She names Margot’s presence as safety long before Margot does, and in the long-time-jump she becomes the bridge between past love and present closure. Winter’s steadying intelligence invites Margot into stepfamily care, proving that the maternal script Aaron wrote for her was never the truth.

Polly

Polly is the neighborly deus ex restoration: a brand pro who arrives precisely when Margot’s public credibility collapses. She reads both algorithms and people, offering competence without judgment and turning a sidewalk humiliation into a strategy session.

Polly’s subplot—marriage to Peter, the unseen online betrayals—echoes the book’s themes of image versus reality and the cost of keeping quiet. By helping Margot rebuild while Margot steels herself to tell Polly the truth, she models adult female solidarity that is practical, funny, and brave.

Peter

Peter is a low-visibility antagonist whose offstage infidelity pressures Margot to act on behalf of another woman, not just herself. He is a study in digital duplicity—harm conducted in DMs and side accounts—which extends the novel’s critique of curated personas.

Peter’s presence forces Margot to measure integrity by what she will risk telling a friend, and her resolve to expose him becomes a rehearsal for choosing honesty over comfort. In narrative economy, he sharpens the contrast between the kindness of Henry and the small selfishnesses that corrode a household.

John

John’s smug deceit in the opening tableau sets the book’s tonal and thematic baseline: Margot’s forensic eye, her refusal to be gaslit, and the comedic sting that follows. The ring mark and baby spit on his collar are tiny meteorological readings—microclues that forecast a larger weather system of lies—and her exit with the takeaway meal reclaims dignity with flair.

John prefigures the tax that women pay for vigilance and the satisfaction of naming patterns early, priming readers to read red flags as data rather than drama. His function is to clarify that Margot’s standards are not cynicism but self-respect.

Charlie

Charlie and the producers who greenlight Weather or Not embody the gatekeeping and opportunity of media ecosystems that thrive on spectacle. They first fail Margot through a scam that dents her public trust, then offer the platform that reframes her expertise as service to children.

This arc lets Margot transmute humiliation into craft, and it makes her on-screen persona an earned identity rather than a viral accident. Their presence widens the novel’s canvas from romance to vocation, showing that the forecast Margot learns to deliver is as much emotional climate as cloud charts.

Cheddar

Cheddar, the comically gigantic cat, is more than mascot; he is an emblem of domesticity returning to a home scorched by fear. His inclusion in the show and his steady comfort during Margot’s solitude are small but persistent notes of levity that counterbalance visions and betrayals.

Cheddar’s growth across months mirrors Margot’s: both become larger than expected, a joke that lands because it is also true. In a story where prediction tempts paralysis, a cat who simply exists and sprawls is a reminder that some loves are delightfully untheorized.

Margot, Eve, Jules, Lily

Together the four friends form the book’s living barometer, measuring pressure systems of loyalty, envy, forgiveness, and repair. Their shifts—from bonded girls to wounded adults to a tentative new alignment—chart how female friendship can be both the site of greatest harm and the resource for healing it.

Each woman holds a different stance toward endings, and their interplay teaches Margot that certainty about the future is less useful than clarity about values in the present. As the quartet reconfigures, the novel argues that the bravest forecast is not whether rain will fall but whether we will show up with umbrellas for one another.

Themes

Science, Control, and the Limits of Prediction

Weather is Margot’s language for managing chaos, and I Know How This Ends treats meteorology as more than a profession: it is a worldview. She treats dating like a field study with fixed variables (same restaurant, same weekday, identical rules), catalogues red flags as if they were wind speeds, and introduces herself through tidy data points.

The method grants a sense of safety after betrayal, yet the narrative keeps showing how human systems refuse to behave like stable pressure fronts. Her experiment delivers false confidence: two men named Henry fit her parameters in opposite ways, and the one who looks optimal on paper reveals hostility the moment a social expectation is breached.

The other, messy with real history and responsibilities, becomes the person who expands her life. Visions complicate this theme by challenging the very promise of prediction.

She can glimpse outcomes, but the glimpses are partial, misleading, sometimes frightening; they don’t close the future down so much as widen it with risk. Grandad’s counsel reframes science as interpretation rather than control: observations are fragments, and the skill lies in choosing how to act with incomplete information.

Margot’s eventual shift from hard control to calibrated responsiveness mirrors good forecasting practice: you communicate probability, update models when conditions change, and accept that uncertainty is not failure but the medium in which meaning is made. By the time she launches a children’s show about weather, she has exchanged experiment-as-armor for experiment-as-curiosity, modeling a form of expertise that admits error, adjusts course, and still steps outside with an umbrella when the sky looks doubtful.

Digital Performance, Shame, and the Cost of Visibility

Margot’s influencer life turns selfhood into broadcast, and I Know How This Ends scrutinizes what happens when metrics replace mirrors. The account @MargotTheMeteorologist begins as a pragmatic exit ramp from burnout, then grows into the machine that isolates her.

She calibrates captions, monitors comments, and becomes hypersensitive to narrative framing—so sensitive that a fake sponsorship detonates not only her income but her sense of credibility. The novel tracks the physiology of shame in a networked age: the late-night doomscrolling, the compulsion to surveil Lily through a burner account, the stomach-dropping exposure when a neighbor overhears her outburst and recognizes the public persona beneath the private collapse.

Visibility promises connection yet amplifies judgment; it allows communities but erodes boundaries. Smale’s choice to give Margot a neighbor, Polly, who understands brand repair from the inside adds nuance: platforms can be tools if wielded with values rather than vanity.

The arc also interrogates the aesthetics of female likability online. Margot’s matter-of-fact, nerdy clarity draws followers, but audiences and sponsors punish her misstep at a scale that dwarfs the offense, echoing how women are disciplined for appearing too confident or imperfectly apologetic.

Recovery involves neither apology tours nor rebranding stunts; it comes through honest labor (the children’s show pitch), community (friends and family), and a redefinition of audience as the kids she wants to teach rather than a faceless swarm to appease. The result is a tempered presence: she still speaks to a camera, but the camera is pointed at weather and wonder, not at self-surveillance.

Friendship, Betrayal, and Repair

The relational spine of I Know How This Ends runs through Eve, Jules, and Lily, showing how friendship can be both sanctuary and site of moral damage. The early clinic scene with Eve codifies the group’s long-standing tenderness; Margot’s humor and steadiness function as ballast during a procedure saturated with uncertainty.

Yet the Lily revelation—engagement to Aaron, pregnancy, and the earlier affair—rips the group’s origin story. Smale resists the easy binary of loyalty and treachery; instead the book examines complicity, secrecy, and the slow erosion of trust.

Jules’s hidden contact with Lily hurts not only because of divided allegiance but because it rewrites the past retroactively: if Jules knew, then who was standing beside Margot during the breakup months? The later confrontation opens a path rarely given space in breakup narratives: forgiveness that does not erase harm yet restores moral agency to everyone involved.

Margot’s embrace of Lily is not saintly abdication; it is the product of months of grief-work, Henry’s steadying presence, and the recognition that clinging to hatred keeps her tethered to Aaron’s story. Eve’s eventual pregnancy draws the circle tighter and reminds the trio that shared futures can be reimagined without pretending old wounds never existed.

Not every tie survives in the same form—Jules’s role diminishes, then surfaces in complicated ways—but the book insists that adult friendship is dynamic, sometimes episodic, and still central. Repair, when it arrives, is specific: a coffee invitation, a confession about the anonymous comments, a refusal to participate in a performative bridesmaid script.

The theme lands on discernment rather than sentimentality: love your people, set boundaries, and let some relationships change shape without calling that failure.

Modern Dating, Misogyny, and Boundaries

Pasta La Vista is both stage and lab bench, a weekly return that exposes the grind of contemporary dating and the gender scripts that keep reasserting themselves. In I Know How This Ends, microaggressions pile up as case studies: the married man who treats the app as a playground, the charming fireman who converts a polite offer to split the bill into an accusation of female arrogance, the flood of hostile texts that follows a woman’s refusal.

Each episode sharpens Margot’s boundary-setting rather than dulling it. Witty dismantlings of hypocrisy are not just comic relief; they are acts of self-defense in a culture that sometimes treats a woman’s no as a public challenge.

The waiter Henry’s counterexample matters precisely because he is not flawless or frictionless. He forgets to call when work implodes, hates confrontation, and carries grief; but he observes, remembers, and apologizes without theatrics.

The book suggests that safety is less about profile optics and more about how a person behaves in rupture: whether they escalate, sulk, or collaborate. Margot’s rules—consistent venue, capped number of first dates, meticulous documentation—begin as boundary scaffolding and calcify into avoidance.

The pivot arrives when she can hold two truths at once: boundaries protect, and they cannot substitute for courage. The restaurant’s staff sickness, the babysitting night with Winter, the axe-throwing date—these are unscripted deviations where intimacy grows because the script is abandoned.

The theme becomes a quiet manifesto: refuse entitlement, pay attention to patterns, and choose partners by how they honor your autonomy when things don’t go to plan.

Grief, Continuing Bonds, and the Ethics of Love After Loss

Henry’s widowhood and Winter’s motherless childhood complicate the romantic arc, pressing I Know How This Ends to treat grief as ongoing relationship rather than past event. The oak tree where Winter speaks to the mother she never met is one of the book’s most luminous scenes, and it reframes mourning as dialogue rather than silence.

Henry’s care for Margot when she is ill—gentle, practical, unshowy—emerges from this ethic of ongoing love: tending the living does not diminish fidelity to the dead. Margot’s losses differ in texture but parallel in effect: the broken engagement, the betrayal by a best friend, the career identity that collapsed under burnout.

Her first response is shuttering; her second becomes ritualized exposure through scheduled dating; her third, made possible by Henry and her grandfather, is acceptance that love after pain is not a betrayal of what came before. The axe-throwing scene is not simply catharsis; it is consent to be witnessed in anger without being reduced to it.

Later, the long-horizon vision of eventual separation threatens to poison the present with anticipatory grief. The book’s answer is neither denial nor preemption; it is an ethic of presence.

Love here is bound by honesty about endings and accompanied by a promise to make decisions at the moment they arrive. Even the fifteen-year time jump refuses melodrama.

The marriage ends, but the shared history remains dignified, and Winter’s continuity with both adults affirms that bonds can be reconfigured without erasure. Grief, then, is not cured; it is carried, integrated into a life spacious enough to include new vows, work that matters, and Christmases where feared losses do not occur.

Foresight, Choice, and the Philosophy of Time

Visions might have reduced the story to determinism; instead, I Know How This Ends argues for agency inside foreknowledge. Margot’s glimpses are concrete—lilac walls, a pink-star jacket, a screwdriver, an exact street—but they are also fragmentary.

Acting as if fragments are verdicts nearly costs her the relationship that will shape her next decade. Grandad’s parable about the figurine is crucial: knowing a shard of future does not grant mastery over causality; it tempts you to force outcomes or flee them, either of which distorts the life you actually have.

The pact Henry proposes—stay, and decide when the foretold moment arrives—transforms foresight from a cage into a form of shared planning. Time becomes collaborative rather than oppressive.

The final meeting in Bristol, seen from future-Margot’s perspective, completes the experiment: foreknowledge can coexist with tenderness, and endings can be honored without panic. Crucially, the visions also teach positive risk.

Early on, Margot interprets images of domesticity as a warning; later, she recognizes them as a map of desire, prompting the children’s show pitch and a posture toward Winter that is generous rather than defensive. The book invites a practical metaphysics: act as though multiple futures are plausible, treat glimpses as weather advisories rather than fate, and allow commitments that are meaningful even if they are not permanent.

In this frame, love and work are not gambles made foolish by uncertainty; they are informed choices within probabilities, dignified by the courage to show up knowing that storms, in some form, are always somewhere on the horizon.

Family, Intergenerational Wisdom, and Distance

Across continents and kitchen tables, I Know How This Ends explores how families teach resilience. Margot’s parents in Australia embody both the annoyance and comfort of persistent parental scripts: nagging about boxes and jobs, affectionate misfires on video calls, the ache of exile soothed by technology.

The gift is not advice but presence. Grandad, meanwhile, gives her the two tools she lacks: permission to name what she fears and a story that reframes foresight.

His blindness subplot literalizes what the visions already suggest—seeing is not the same as knowing. Margot’s botched attempts to test his safety (hiding shoes, scanning calendars) reveal a love that can become controlling when mixed with anxiety; his response keeps dignity at the center.

Their scenes are threaded with jokes, craftsman’s detail, and gentleness; when Margot discovers the bird calendar clue that predicts his death, the book honors grief without spectacle. The family arc also includes chosen kin: Polly turns from neighbor to ally, applying pragmatic wisdom to the digital crisis and offering childcare-limited expertise that corporate culture often underestimates.

Even Winter’s acceptance evolves through family practices—shared adventures, truthful acknowledgment of her mother, respect for her intelligence. Distance—of miles, of years, of divergent life phases—remains real, but it is bridged by small technologies and smaller rituals: a smart TV call, a toy panda carried between generations, a rain video filmed for children who might become climate-curious adults.

The result is a portrait of kinship that values reliability over rhetoric and steady, domestic kindness over grand gestures.

Motherhood, Care, and the Making of a Blended Life

Margot enters Henry’s world through Winter, not around her, and I Know How This Ends treats that entry as moral formation rather than romantic accessory. Winter is skeptical, smart, and wounded by adult decisions she did not get to make.

Margot’s patience—sitting outside the locked door, consenting to a mock runaway, inventing an “adventure” that respects Winter’s pace—models a care ethic grounded in attention and play. The oak tree scene reframes the conversation about motherhood that Aaron once poisoned.

He convinced Margot she was not maternal; Winter proves otherwise, not because Margot suddenly longs for motherhood as a destiny, but because she practices it as conduct: listening, telling the truth, protecting without smothering. Later visions of a wedding and a small son named Gus express desire without collapsing a woman’s completeness into reproduction.

The book is careful about labor as well: caretaking includes the unglamorous tasks—nursing someone through the flu, tolerating messy haircuts, rearranging work for school schedules. Henry’s openness about Amy, and Margot’s refusal to compete with a memory, create a greenhouse where a child can love both the past and the present without apology.

The long view matters. Even after Margot and Henry part, Winter’s bond persists, culminating in the future street meeting where she recognizes and thanks the version of Margot who once chose this life.

The theme insists that family is something you do, not only something you are; the verb makes room for step-roles, for endings that do not cancel beginnings, and for children who carry the best of several homes.

Work, Purpose, and Ethical Reinvention

Career in I Know How This Ends is not just plot machinery; it is a mirror for moral growth. Leaving the Met Office burns up a professional identity; building @MargotTheMeteorologist reveals both entrepreneurial grit and the thin oxygen of constant optimization.

The “Thunderwear” fiasco is the book’s sharpest indictment of hustle culture: scarcity plus algorithmic pressure makes you say yes to nonsense, and the market’s punishment is swift and often disproportionate. What follows is not a tidy comeback montage but a values reset.

Polly’s counsel, the handmade pitch for Weather or Not, the decision to center children’s curiosity—all of this shifts Margot from self-branding toward service. She stops treating audience size as validation and starts measuring impact through wonder.

Even the aesthetics of her work change: instead of airbrushed perfection she embraces practical demonstrations, humor, and frank acknowledgments of error. The show’s success is important, but the process matters more: she learns to ask for help, to share credit (Cheddar’s accidental stardom is a running joke about how uncontrollable virality is), and to accept that reputation is cumulative and fragile.

The future epilogue confirms that purpose is not static. Careers evolve, partnerships end, and integrity resides in how you carry your name through those shifts.

In choosing educational broadcasting over click-driven content, Margot practices a public ethics consistent with her private growth: tell the truth, teach what you love, and keep your audience’s good above your image. Reinvention, the novel suggests, is not about becoming unrecognizable; it is about aligning talent with conscience, again and again, as conditions change.