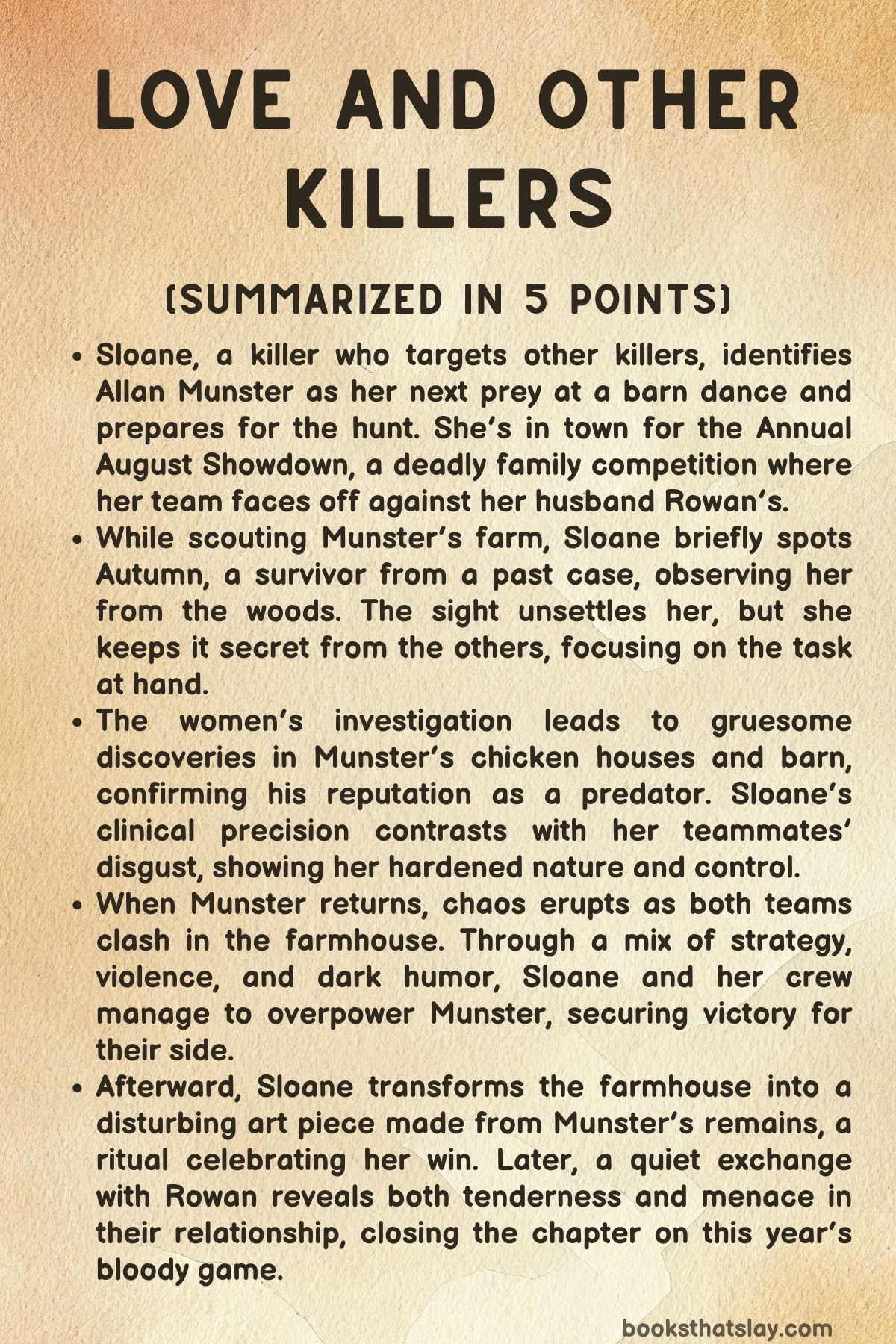

Love and Other Killers Summary, Characters and Themes

Love and Other Killers by Brynne Weaver is a darkly comic and razor-sharp thriller that turns the traditional cat-and-mouse narrative upside down. It follows Sloane, a calculating woman who makes it her mission to hunt serial killers for sport.

Each year, she and her husband, Rowan, face off in the macabre “Annual August Showdown,” a family competition that blurs the line between love, obsession, and justice. In a world where morality is flexible and danger is thrilling, Sloane proves herself both predator and protector. Weaver’s novel blends violence, strategy, and twisted intimacy to explore what happens when killers become prey.

Summary

Sloane arrives at a barn dance near Linsmore, where she quickly identifies Allan Munster—a local farmer selling homemade whiskey—as the man behind the string of forest murders attributed to the “Sproul Forest Specter. ” With her sharp instincts and a practiced eye, she notes his logo, demeanor, and address, mentally marking him as her next target.

She’s not in town by coincidence; the annual hunting competition known as the “August Showdown” is about to begin. Her team—the irreverently named “Sticker Bitch Crew” consisting of Sloane, Lark, and Rose (along with Rose’s mischievous raccoon, Barbara)—will be facing off against the Kane brothers: Rowan, Lachlan, and Fionn.

Rowan happens to be her husband, and their shared profession of hunting killers has become both their bond and their battleground.

At their rental house, the Kane brothers overindulge in Munster’s potent moonshine, a reckless move before the coming hunt. Meanwhile, Sloane prepares for her operation with precision.

She creates one of her signature “webs,” intricate installations of fishing line that will later display the remains of her kill—an eerie, artistic signature that turns murder into a kind of performance. Lark and Rose assist her in assembling materials, and together they finalize their plans for the hunt.

At dawn, both teams gather on a ridge overlooking Munster’s property. The rivalry between them simmers beneath sharp banter until Sloane bargains for a twenty-minute head start.

Through binoculars, they confirm Munster lives alone and watch as he drives away in his truck. During surveillance, Sloane catches sight of Autumn—the survivor from a previous case involving the killer Harvey Mead.

Autumn watches from the treeline, wearing a plaid shirt Sloane once gave her. Their silent exchange is brief, and Sloane decides not to tell the others, sensing that Autumn’s presence means acknowledgment rather than threat.

Sloane’s team begins its search at the edge of Munster’s land, starting with a filthy chicken house reeking of ammonia. Inside, Sloane uncovers a horrifying pile of pulverized flesh and bone that the chickens are pecking at.

She spots a fragment of a hyoid bone—evidence that confirms Munster’s connection to a missing hiker named Martin Jeoffries, one of the Specter’s rumored victims. Rose is sickened by the sight, while Sloane calmly pockets the bone for later.

They move on to the farmhouse, noting the absence of cameras or guard dogs. The interior is disturbingly normal: lace doilies, bland art, a scrubbed cleanliness that hides the rot beneath.

While Sloane explores, she sends Rowan a teasing photo of Munster’s ice cream as a taunt. In the barn, Rose discovers a freezer full of severed hands—undeniable proof of Munster’s crimes—and is again overwhelmed by nausea.

With Munster’s return imminent, Sloane hides in a closet by the entryway, waiting to ambush him. Unexpectedly, Rowan slips into the same hiding spot.

Their playful tension resurfaces as Sloane quietly loops fishing line around his wrist, tying him to a vacuum handle—her dominance as effortless as it is deadly.

Munster’s truck pulls up, but instead of heading to his machine shed, he goes straight to the house where Lachlan is positioned. Lark intercepts him outside, posing as “Meadow,” a cheerful fan of his moonshine who asks to use the bathroom.

He falls for the act and lets her inside. The moment he steps through the door, chaos breaks loose.

Rose grabs a hatchet; Munster throws a lamp; Rowan shields Sloane from the shattering debris. Lachlan blocks the exit but refuses to interfere, not wanting to rob the women of their victory.

The fight becomes a frantic melee. Munster smashes Lark’s legs with a metal chicken statue and makes for the door.

Rose hurls the hatchet, embedding it in his buttock. Rowan, still tied, swings the vacuum like a club, striking Munster’s skull.

Sloane finishes it cleanly—drawing Rowan’s knife and slicing Munster’s throat.

The women claim victory. The men can only watch as Sloane’s calm efficiency seals the outcome.

Despite losing, Rowan’s pride in his wife outweighs his defeat. Together, they transform Munster’s living room into Sloane’s signature installation—a morbid web of fishing line and flesh.

Rowan anchors the lines; Lark threads Munster’s limbs into suspension; Rose and Fionn clean up the scene. The raccoon, Barbara, is confined to the bathroom after stealing codeine.

Sloane meticulously arranges each trophy: slices of skin representing past victims, Munster’s eyes as central nodes, and Martin Jeoffries’s hyoid bone positioned beside tissue from Munster’s throat. It’s both art and message—a clue she intends investigators to find, proof that she hunts those who deserve it.

Rowan, in awe of her precision, names her the “Orb Weaver.

Later that night, as they rest, Sloane tells Rowan about seeing Autumn. He reacts with concern, fearing discovery, but Sloane reminds him that Autumn has known of their secret for years and never spoken.

To her, Autumn’s appearance was likely a silent thank-you—an acknowledgment of survival on the anniversary of Harvey Mead’s death.

Their conversation drifts back to their rivalry and mutual attraction. The tension between competition and affection fuels their relationship, and they end the night together, both physically and emotionally entwined in their shared darkness.

As they fall asleep, Sloane is already anticipating the morning, ready to remind everyone that the win—and the kill—belonged to her.

The story closes on the paradox of Sloane’s world: a woman whose lethal skill and meticulous artistry make her both monster and avenger. Her victories are bloody, but they are hers alone, carved out of a life where love and violence coexist without apology.

Characters

Sloane

Sloane is the dark heart and calculating intellect of Love and Other Killers. She is a serial killer who preys exclusively on other serial killers, which gives her a paradoxical morality—an avenger of victims, yet a murderer herself.

Her methods are meticulous, almost ritualistic, as seen through her creation of “webs,” intricate installations symbolizing both her artistry and her control over chaos. Sloane’s sharp perception allows her to immediately identify Allan Munster as the Specter, underscoring her lethal intuition and investigative acumen.

Despite her cold pragmatism, her interactions with Rowan reveal a rare vulnerability. Their relationship, built on shared violence and rivalry, contains a twisted tenderness that humanizes her amid the brutality.

Sloane’s moment of silent understanding with Autumn—the survivor she once spared—shows her complexity: a predator capable of empathy and recognition of shared trauma. She exists in a moral gray zone, both destroyer and protector, embodying the idea that monstrosity can coexist with conscience.

Rowan Kane

Rowan, Sloane’s husband and fellow hunter, mirrors her ruthlessness but contrasts in temperament. Where Sloane is methodical and quietly lethal, Rowan is more visceral and physical—a force of nature wrapped in charm.

His pride in Sloane’s skills and his willingness to let her lead in the hunt highlight his respect for her abilities, even when competition brews between them. Rowan’s humor and protectiveness—shielding Sloane from a shattered lamp or tying himself into her chaotic schemes—add dimension to his savagery.

He thrives in the blood-soaked dance of their marriage, where love manifests through violence and mutual recognition. The tenderness he displays privately contrasts sharply with his ferocity during the hunt, suggesting that his devotion to Sloane grounds his otherwise feral existence.

Lark

Lark, a member of Sloane’s “Sticker Bitch Crew,” provides levity and versatility to the story’s otherwise grim tone. Her cleverness and ability to adapt—seen when she disarms Munster with charm under the alias “Meadow”—demonstrate her psychological agility.

Lark’s role as the team’s tactical charmer offsets Sloane’s severity and Rose’s impulsiveness. Yet beneath her brightness lies resilience and pain, masked by humor.

Her ability to maintain composure in a world of horror marks her as both survivor and accomplice, one who thrives on danger yet holds onto slivers of humanity through camaraderie and laughter.

Rose

Rose stands out for her emotional volatility and grim humor, a balance between fragility and fierce loyalty. Her repeated vomiting during discoveries of human remains underscores her sensitivity, yet she never flees from the mission.

This duality—repulsion intertwined with determination—makes her one of the most human figures in the crew. Rose’s impulsive energy peaks when she hurls the hatchet that ultimately brings Munster down, showing that her courage erupts in chaos.

The inclusion of her raccoon, Barbara, further amplifies her eccentricity, softening her brutality with absurdity. Rose embodies the uneasy coexistence of innocence and savagery within Sloane’s world.

Allan Munster

Allan Munster, the so-called Specter, represents the archetype of the hidden predator—ordinary on the surface, monstrous underneath. His rural demeanor and moonshine operation disguise his savagery, a darkness mirrored in his victims’ fates.

Munster’s farmhouse, sanitized yet horrifying in its secrets, becomes a physical extension of his psyche: deceptively domestic but soaked in death. His confrontation with Sloane and her team is a symbolic reckoning between predators, his brutality undone by Sloane’s superior precision and intelligence.

Munster’s demise not only secures the women’s victory in the game but also serves as poetic justice—his own weaponized hospitality turned against him.

Autumn

Autumn, though peripheral in presence, carries immense symbolic weight. As a survivor from Sloane’s past encounter with another killer, she represents the aftermath of horror—the human face left behind.

Her silent appearance on the ridge, dressed in the plaid shirt Sloane once gave her, evokes themes of recognition and redemption. Autumn is a living testament to Sloane’s selective morality; she is both a ghost from the past and a reminder that not all victims must die for Sloane’s vengeance to have meaning.

Her unspoken acknowledgment of Sloane bridges the worlds of predator and prey, suggesting a strange form of gratitude and closure.

Lachlan and Fionn

Lachlan and Fionn, Rowan’s brothers and rivals in the annual hunt, serve as reflections of the story’s familial competitiveness and ritualized violence. Lachlan’s insistence on fairness—refusing to steal the women’s victory despite having the chance—shows an unexpected sense of honor within their blood sport.

Fionn, though less prominent, grounds the chaotic scenes with practical support, assisting in cleanup and maintaining the gruesome order that follows their games. Together, they represent the normalization of violence within the Kane family, where murder becomes not only sport but a perverse form of bonding.

Barbara

Barbara, Rose’s mischievous raccoon, adds an element of absurd comedy that offsets the novel’s unrelenting darkness. As a symbol, Barbara mirrors her owner’s chaotic loyalty and unpredictable energy.

Locked away during the bloodier scenes, she becomes a reminder of innocence corralled by madness, a creature existing within a world that defies morality and reason. Barbara’s presence humanizes the team in strange ways—showing that even killers can have attachments that are wild, inconvenient, and endearingly alive.

Themes

Justice and Moral Ambiguity

In Love and Other Killers, the notion of justice exists in a distorted, morally ambiguous framework where the hunters are as tainted as the hunted. Sloane’s identity as a serial killer who hunts other serial killers creates a paradoxical moral structure that questions what justice truly means in a world where traditional ethics are void.

Her actions, though driven by the intent to eliminate evil, blur the line between retribution and indulgence. The so-called “Annual August Showdown” transforms killing into competition and entertainment, removing any ethical weight from the act itself.

By turning murder into a game, the book dismantles the idea of law and order, positioning Sloane and her companions as vigilantes who believe in their own version of righteousness. The chilling calm with which they approach death reveals how desensitized they have become, not out of necessity, but habit.

Justice in this narrative is not a moral act; it is a performance—staged, rehearsed, and perfected through ritual. The act of displaying the victims in Sloane’s macabre “web” further exemplifies this point: it becomes less about punishing evil and more about creating art from atrocity.

Yet the fact that Sloane leaves clues for investigators suggests an underlying need for accountability, as though she still wishes the system she defies to recognize her version of justice. Through Sloane, the novel poses a haunting question: when justice is stripped of its ethical foundations, does it become indistinguishable from vengeance?

The Duality of Love and Violence

The relationship between Sloane and Rowan encapsulates the volatile coexistence of affection and brutality that defines Love and Other Killers. Their marriage is built not on tenderness but on shared carnage—a love story forged through blood rather than sentiment.

Their interactions oscillate between genuine intimacy and lethal collaboration, making it difficult to discern where passion ends and predation begins. This duality is central to their connection; violence becomes their language of love, the way they communicate respect, desire, and dominance.

When Sloane kills Munster using Rowan’s knife, the act is both victory and intimacy—an assertion of her prowess and a reaffirmation of their partnership. Their physical and emotional unity thrives in chaos; the more they kill together, the closer they seem to grow.

The book thereby reframes love not as an antidote to violence but as an extension of it, a force that can coexist with savagery without contradiction. The tenderness they display afterward—banter, shared exhaustion, quiet satisfaction—feels disturbingly normal, showing how deeply violence has been woven into their emotional core.

In this sense, the novel explores the dangerous psychology of those who find beauty in destruction and affection in domination. Love here is not redemptive; it is corrosive, binding the characters through shared sin rather than forgiveness.

Power, Control, and the Performance of Identity

Power in Love and Other Killers operates through manipulation, spectacle, and control—particularly in Sloane’s behavior as both predator and artist. Her entire persona is an act of dominance, from the way she toys with Rowan and her opponents to how she transforms a corpse into a meticulously arranged “web.

” The physical act of killing is less about survival and more about asserting mastery—over others, over fear, and perhaps over her own fractured psyche. Every decision she makes, from luring Munster to orchestrating his death, demonstrates her need to control every aspect of her surroundings.

Even within her marriage, control defines her sense of self; her playful taunting of Rowan and her insistence on recognition as the victor of the Showdown reveal how her self-worth depends on winning. The “web” installation serves as a visual metaphor for this obsession—it is a structured display of chaos, a tangible manifestation of how she organizes and beautifies death to affirm her identity.

Yet her control is not absolute. The brief reappearance of Autumn destabilizes her confidence, reminding her that not all elements of her past can be contained or silenced.

This tension between control and vulnerability gives the character dimension, suggesting that beneath her precision lies fear—a fear of insignificance, of losing the narrative she has built around herself. The book thus portrays identity as an ongoing performance where power is both armor and prison, a spectacle designed to conceal the emptiness underneath.

The Banality of Evil and Desensitization

One of the most striking aspects of Love and Other Killers is how ordinary violence feels in the lives of its characters. Murder is not treated as a moral crisis but as an everyday task—something to be strategized, joked about, and celebrated.

The casual way the group discusses their kills, or the fact that they transform Munster’s body into a decorative installation, reflects a profound desensitization to death. Evil in this story is not monstrous or exceptional; it is routine, procedural, and almost domestic.

The farmhouse setting, with its doilies and mundane décor, intensifies this dissonance—the horror is framed within normalcy, showing how easily savagery can coexist with the ordinary. The characters’ humor, their rivalry, even their affection all unfold against a backdrop of brutality, making violence appear not shocking but familiar.

This normalization of cruelty comments on the human tendency to adapt to horror, to rationalize what should be unforgivable. Sloane’s group represents a society so numbed by violence that it becomes an art form rather than a transgression.

The chickens pecking at human remains, the freezer filled with hands—these images are grotesque not because of their gore but because of how calmly they are processed by those who encounter them. The novel thus captures the slow erosion of empathy that comes from living in perpetual proximity to death.

Evil, in Weaver’s world, does not scream; it murmurs, blending seamlessly with laughter, competition, and love.